Nikola Tesla Articles

The Genius Who Walked Alone

Nikola Tesla was a great inventor and also a prophet without honor

Counter-espionage wheels started turning early on the morning of January 8, 1943. Anxious FBI agents slipped into a room in the Hotel New Yorker where, late the night before, a chambermaid had discovered the body of Nikola Tesla, dead at 86, regarded by many as the greatest scientific genius of his time.

For years, Tesla had been making scientific predictions so fantastic as to be literally out of this world. Of late he had been working or so he said on revolutionary new weapons powerful enough to annihilate armies at a single blow.

There was only one Tesla, and the story might-incredible as it sounded-be true. The old man's safe might hold these secrets, and JUNE, 1955 the Government could not risk the chance of enemy spies getting there first.

Half hoping to find something which would bring a sudden and decisive end to World War II, the G-men broke open the dead man's strong box. If anything of importance was discovered, it has never been revealed.

Yet, their quick action was justified, for you could never be sure about Tesla, one of the strangest men who ever lived. Most people took him with a grain of salt, yet no serious scientist dared shrug away his claims as nonsense. Not after Thomas Edison tried it and Tesla proved him wrong.

The world's leading physicists and electrical engineers had to eat crow back in the 1880s when Tesla solved a problem they had thought impossible. That one accomplishment the invention of a practical alternating-current motor and generator - put Tesla's name among the world's top scientists.

From his invention sprang the industrial age we live in. For without his alternating current, there would be no mass production of automobiles, aircraft, refrigerators; no great water-power dams and generating plants, no Diesel-electric trains; we could not have developed radio, television or atomic power.

The direct current that Edison worked with - a feeble force at best - could be sent no more than a couple of miles over wires because its power leaked away rapidly into the surrounding atmosphere. Lights near the power station might burn brightly and steadily, but those near the end of the line would be dim and fluttering.

Tesla sold his basic alternating-current patents in 1888, for a million dollars down. By 1895, the first great power station at Niagara Falls had been built, and by the end of 1896, two more Tesla generators had been installed. Within a few years, the pace of life over half the earth had changed from a crawl to a fast gallop - and it has been gathering speed ever since.

The man who, by his brilliant idea of a "rotating magnetic field," changed the face of the earth and the living habits of the human race was a Croat, born in 1857 in Smiljan, a village in what is now Yugoslavia, but was then part of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire.

When he was about six, Nikola Tesla's father, the village priest, was transferred to a larger parish in the city of Gospic. There, the lad grew up and perfected his earliest "inventions." Of these, his favorite was an "engine" powered by 16 June bugs, harnessed in sets of four to spokes which radiated from the drive shaft.

Nikola was a frail lad, often ill; and he nearly went blind from too much reading. He read everything he could get his hands on, not only science but also religion, philosophy, history, literature. By the time he finished high school, he was fluent in French, German and Italian, as well as his native Serbo-Croat.

He got his schooling the best his doting family could afford-at Gospic, Carlstadt, Gratz, the University of Prague and, finally, at Budapest. At the University, he saw his first electric motor, a new type direct-current affair whose brushes and commutators sent out showers of crackling blue sparks.

"If we got rid of those brushes and commutators, with all that noise and loss of energy, we'd have a much better motor," Nikola told his professor. "Perhaps it might be done with an alternating current."

"Nonsense!" barked the professor. "An alternating current would never run anything. You're not the brilliant student I thought you were. Forget it!" But Tesla could not forget. The teacher's ridicule only stamped the idea indelibly on his brain. It became an obsession, a passion how to make an alternating current drive a motor. In every idle moment, wherever he went, he wrestled with this problem.

Tesla's mind had an unusual twist. Almost from infancy, he had been able to see things in his mind's eye so vividly-and in such minute detail that often he had trouble telling the real from the imaginary.

Where the average engineer or inventor would reach instinctively for drawing board, paper and pencil, Tesla would simply switch on that uncanny magic lantern inside his brain. He would fix a mental image there. Then he would alter this detail or that, discard one plan, try another, without ever putting a line on paper.

Years later - from these mental images alone - he could give his workmen exact instructions on how to build each part of a new device, though it was unlike anything ever seen before.

Thus, needing no drafting room and few laboratory conveniences to work on an idea, Tesla could use every spare minute that he had to test and revise his theory of alternating current.

His first real job was manager of a newly organized telephone company in Budapest. But telephone circuits were dull stuff compared with the challenge of that one big idea. He moved to Paris where he became a kind of general trouble-shooter for the Continental Edison Company.

His brain was still chipping away at his big problem, but the trouble was, he couldn't share it with trained men who might have helped him work it out. For whenever he JUNE, 1955 mentioned alternating current to an electrical engineer, the man would look at him as though he were crazy.

But then came the moment when he knew he had solved it. He was walking with a friend in the Bois de Boulogne. Suddenly, he stopped short and began jabbing with his cane at some invisible object in the air.

"See - it works!" he shouted. "It is the rotating magnetic field which causes the armature to turn. It pulls the magnets around with it, causing the shaft to revolve. As I oscillate this switch, causing the current to flow first in one direction, then the other..."

Never mind what his friend thought. Tesla had the answer.

At the office, his colleagues scoffed or looked blank. But the manager, listening to the outpourings of scientific jargon, suddenly thought of his boss back in the United States. If there were some truth in what the Croat said, surely the famous electrical wizard would be smart enough to see it.

So he gave Tesla a letter of introduction to Thomas Edison and urged him to try his luck in America. Thus, Tesla, now 27, arrived in New York. He was handsome, over six-feet-two, with a distinguished head and deep-set blue eyes. His Slavic face was broad across the cheekbones, his dark hair thick, his chin sharply pointed. Of worldly goods, he had the clothes on his back, four cents in cash, the letter to Edison, and the idea which was to change the world.

Edison thought less than nothing of the idea. It seemed so preposterous that he wouldn't even listen - and, of course, Tesla had no drawings with which to try to convince him. But Edison gave him a job, for he had excellent training as an engineer and Edison needed trained men.

Busy with routine electrical work, Tesla waited nearly three years for a chance to turn his mental image into an actual motor he could show to others. In 1887, he was able to borrow enough money to start his own laboratory, and the following year the alternating-current motor and generator were practical realities on a laboratory scale-though much practical engineering would still be needed to fit them to commercial use.

George Westinghouse, another inventor, was the first to see their value. He bought the patents and gave Tesla a job as engineer in his Pittsburgh factory.

But Tesla couldn't get along with the other Westinghouse engineers. From his standpoint, the alternating-current job was done. Even "schoolboys" could now iron out the few remaining kinks. Meantime, his brain had started to hatch even bigger dreams. He went back to his laboratory in New York.

"Be alone-" he once told a science writer. "That's the secret of invention. Be alone-that's where great ideas are born."

Alone he was. In the years that followed, Tesla had many admiring acquaintances, but seldom a friend. After his mother, no woman ever entered his personal life.

His manner toward others was cordial but reserved, distant. His words were as if uttered by some god, sitting on an Olympus high above the rest of humanity. Backed by his fame, those words made a tremendous impression.

He lectured at every scientific center in this country and in all the important capitals abroad. Things which, as yet, existed only inside that amazing brain of his were so real to him, he made them real to his listeners.

He described radar and radio broadcasting and even television. He advocated electro-therapy. He foresaw a day when man would control nature in every respect - even the weather - when machines of all kinds, and the power to run them, would be so cheap that poverty would vanish from the world.

Without wanting to be, Tesla was a superb actor. After listening to him and seeing his wonders, audiences were ready to believe nearly anything.

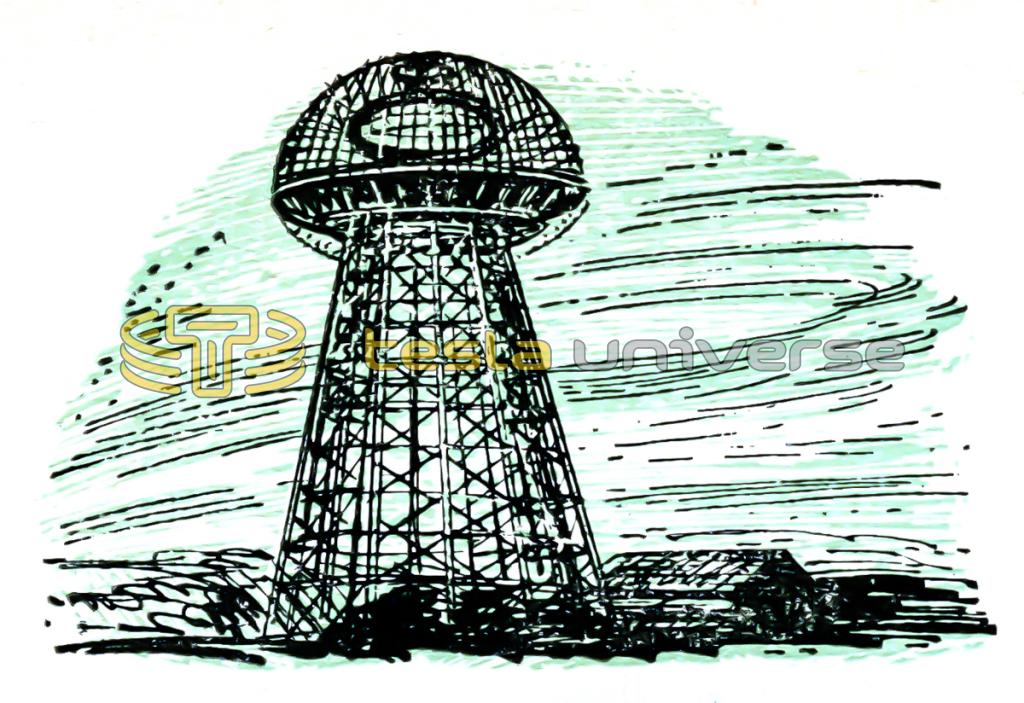

Tesla reasoned that you could sell electric power cheap if you could do away with the millions of poles and insulators, the millions of tons of copper wire used to transmit it from place to place. He thought he knew how to do it - and J. P. Morgan backed him with $300,000.

On Long Island, Tesla built a huge power plant with a 154-foot steel-ribbed tower topped by an enormous mushroom-shaped copper dome. From this dome he planned to bombard the earth's crust with millions of volts of electric energy. The power so added to the earth's permanent charge could be drained off at some other point - any point - on the earth's surface. Thus, it would be possible for electric power to be sent anywhere without conduits, poles or wires. Or so he thought, until he tried it.

In November, 1898, Tesla announced that he could abolish war.

The inventor had designed a small, inexpensive, radio-controlled boat which, through its supposed ability to destroy the biggest battleships, would make great navies useless. Not many years later, he was talking of another super-weapon: a "death ray" which would annihilate whole armies.

Yet Tesla never suspected that the real super-weapon of the future would come from atomic fission. For Einstein's basic notion which led to smashing the atom, he had only ridicule. Alone in his middle age, he had fallen out of step with the world's great thinker.

Not all Tesla's later inventions were fantastic. Some, like his induction coils and oscillators, and pioneer work on "tuned" electrical circuits, were highly important.

Though he never succeeded in transmitting power without wires on a big scale, he did prove that a single wire is enough. And some of his brilliant prophecies inspired the more plodding scientists to work out the practical problems of induction heating, radio-telephone, radar and many other electronic marvels of today.

But as he grew older, he withdrew further and further within himself. His strange prophecies sounded like a voice from another planet. For companionship now, the old man had only his dreams, and they grew stranger with the years. Completely alone at last, a stooped, gaunt figure with thin, silvery hair, he used to slip from his hotel room, buy a bag of birdseed and trudge slowly over to a park where hundreds of pigeons awaited him. These were his friends. They needed him, though the world did not.

When he grew too ill to go out, each day he sent a Western Union messenger to the park. After feeding the birds, the boy was instructed to see if any of them seemed sick. If so, he was to bring them back to Tesla's room where the inventor would nurse them gently back to health.

Perhaps this sad little labor of love showed that the man who changed the world had, at last, discovered a great truth. Perhaps he knew now that the greatest power for good lies not in lonely thought but in a human heart pulsatinglike his own "tuned circuits" - in tune with the hearts of his fellowmen. Or did he ever know? You could never be sure about Tesla.