Nikola Tesla Articles

Latest Discoveries in Wireless Telegraphy

The latest information that comes to us from Signor Guglielmo Marconi, the young and famous wizard of telegraphy, is that he has finally succeeded in preventing other people from stealing, not his thunder, but his lightning. In other words, he has "syntonized" his instruments and brought wireless telegraphy, as it is called, to such perfection that he can send a message direct to the intended destination without any danger of its being intercepted on the way. The trouble with the system hitherto has been that it was too promiscuous in bestowing its favors, for while a message could be sent out from a certain station, there was no certainty that it could not be picked up by any number of "receivers" lying in wait for it at different points of the compass.

The electric waves were likely to conflict also, and if several telegraphic signals were flying through the air at once, there was a likelihood that they would be hopelessly jumbled.

Another defect in the system has recently been remedied, and that is the supposed necessity for using very tall poles or masts in the transmission of messages or signals. In the experiments conducted by Marconi across the English channel the mast used was 177 feet high, though the distance was only 30 miles. Such has been the rapidity with which this invention or discovery has progressed that it was less than two months ago that an authority in electrical science stated in a technical magazine that in order to communicate by wireless telegraphy a distance of 60 miles the wire attached to the instrument should be elevated at least 100 feet above the level of the sea or surface of the earth. But now comes the astounding information that Marconi has transmitted a message that distance - beating his former record by 28 miles - and that it was received on a cylinder only four feet from the ground.

It was predicted a year ago, when experimentation with the wireless system was at its height, that before another year had closed messages would be flitting across the Atlantic from Europe to America without wires or cables, but that in order to do this they would have to be sent from balloons a mile or so up in the air. The bugaboo the electricians causelessly feared and reckoned against was the curvature of the earth, but it has transpired that the electric waves take no account of solid matter any more than of the impalpable ether, apparently, and when liberated go straight to their destination with the rapidity of light itself.

So now the two greatest objections to the forthcoming universal application of the wireless system have been removed or surmounted, and, extending the time a little, we shall doubtless witness here the transmission of messages across the Atlantic without any difficulty. One of the latest applications of the "Hertzian waves" is as an auxiliary in torpedo warfare, for a young naval officer has succeeded, he claims, in harnessing them to his submarine boat and steering it without a hitch wherever he willed by a receiving apparatus which acted upon a set of magnets and manipulated the rudder.

Again, they are not only telegraphing without the use of direct wires, but also telephoning, and it is expected that telephony will soon be immensely developed along these lines. In fact, when we consider the forces brought into conjunction in this wonderful discovery: that they deal with the occult springs of nature itself and its vastest phenomena, we may be prepared for any development short of communicating with the planets and the stars. There are some sanguine individuals, even, who predict that we shall some time be enabled to communicate with Mars and the Martians through these waves that oscillate 100,000,000 times a second.

The first to send messages along "nature's great highways in the aerial ocean" were those who signaled by means of fires and beacon lights on towers and mountain tops, and it is claimed that this system of signaling was brought to perfection 200 years ago. A working telegraph (by semaphore) and a code was in use during the French revolution, as early as 1792, and it had been discovered 45 years before that electricity would force itself through considerable lengths of wire, the earth or water taking the place of a return wire and completing the circuit. Franklin was able to transmit electric shocks across the Schuylkill in 1748, while in 1794 a German scientist used the electric spark, in telegraphy, but by employing 36 wires each way.

Telegraphy, like every other great invention, was not communicated to the world by any one men, but owes its being to the researches of philosophers and scientists during many years. One of these to whom we are most indebted is Professor Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian institution at Washington, who in 1831 devised an instrument with the essential features of the

Morse register and made great improvements in electro magnets. It was in 1837 that Morse's telegraphic instrument, so simple and efficacious that it is used in a modified form today, was first exhibited, and that same year Steinheil's telegraph, extending 12 miles, with a single wire and the use of the earth to complete the circuit, traced lines and dots on ribbons of paper. Many great minds were engaged upon the problem of telegraphy when Morse filed his caveat for a patent in 1837, and that very year Wheatstone and Cooke in England took out a patent for an instrument of their own.

It is just 60 years since a patent was granted Morse for his telegraphic instrument and 56 since he brought it into practical use over the first line erected, between Washington and Baltimore. Since then has come the vast development of the land lines and the submarine cables - the first of the latter, by the way, having been laid between Governors Island and the Battery, New York, and almost immediately carried away on the anchor of an intruding vessel.

As with the discovery, or, rather, the development, of telegraphy by means of wires and cables, so it was with this latest and in some respects more wonderful science of wireless telegraphy. It is a question for experts to decide whether Faraday or Henry was the true discoverer of electric waves or the propounder of a theory respecting their propulsion, but Clerk Maxwell, the Scotch physicist who died so late as 1879, crystallized their theories into fact by his extensive experiments and proved that the waves or undulations of electricity could be transmitted through the air in the same manner as light and with the same rapidity.

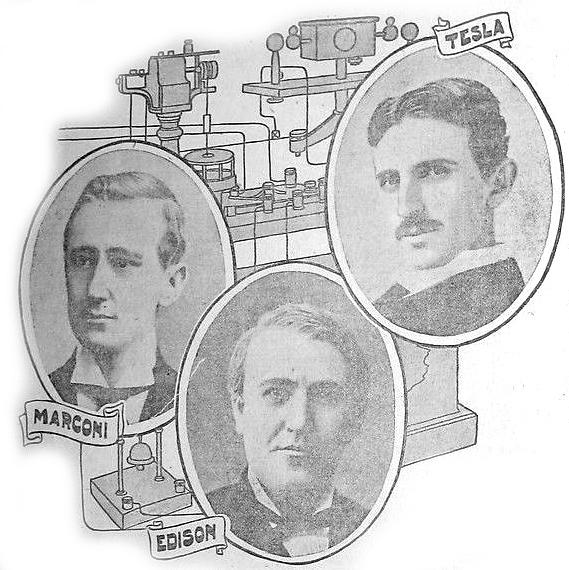

A German scientist named Heinrich Hertz verified these theories and experiments, carrying forward the work to the time of his death in 1895, and made such progress that the undulations were named, after him, "Hertzian waves." The Russian Popoff successfully sent messages by them five years ago, in 1895; Branly and Ducretet, Frenchmen, invented receivers for registering them, so that men of several nationalities are entitled in the honor of having established the law that governs the phenomena. Suddenly there appeared one of another nationality, an Italian named Righi of Bologna, who had hardly published his account of some improvements he had made when his laurels were wrested from him by his pupil, Guglielmo Marconi, then only 21 years old. It may have been by intuition, or from a remarkable grasp of the subject, but there is no doubt that Marconi, like the great American inventors, Thomas A. Edison and Nicola Tesla, is a "natural born genius," and was able to advance farther than any of his predecessors. He availed himself of all the inventions and discoveries that had been made before and has been declared a "practician," rather than an inventor. But, whatever his peculiar gift, whether as an originator or adapter of other men's inventions, it was through him that wireless telegraphy received its greatest impetus.

No one man can claim the glory of achieving this great discovery, and it might seem unjust to grant one a patent, and refuse it to another. In fact, the validity of Marconi's patents has been questioned in some particulars, the French, for instance, advancing the claim for precedence in the practical use of electric waves for transmission of messages, and especially for M. Branly's invention of that most essential feature of the receiving instrument, the "coherer." Indeed, the history of all past discoveries of like magnitude teaches us that the individual is nothing - the cumulative impulse of the century or the cycle is everything. For a few years, say for the duration of a patent, one man or company may control the invention and receive his usufruct, but in the end the world will be the beneficiary.

However, it was Signor Marconi, a Florentine by birth, but whose mother was an English woman, who gathered all the threads of the various inventions together and placed them before the public as a concrete whole. Instead of trying to prove or disprove the theory of wave propulsion or propagation, he started out by accepting it as a hypothesis, and, assuming that messages could be sent by them a hundred yards, there was no reason why they could not be sent a thousand, or as many miles.

He finally succeeded in perfecting an apparatus by which theoretically he could send a message through the air at least a hundred miles, and then began his task of working up to its realization. He readily convinced the Italian government to the extent of receiving its support and the adoption of his devices for use in its navy. Then he went to England, where, though at first unsuccessful, he finally proved to the British admiralty the immense value of his achievements, and they were adopted by the government. His great feat in the fleet maneuvers by which a supposititious transport bringing supplies from Canada was discovered 80 miles away by the convoy sent in search of her, attracted great attention at the time, and his subsequent establishing of uninterrupted communication between the shore and the Prince of Wales yacht while on a cruise set the seal of approbation upon his schemes.

Although yet a young man, only 26 years of age, Marconi has been the recipient of high honors from scientific societies and of substantial emoluments and decorations. His visit to this country last year, when, on the occasion of the international yacht race, he fully established the reputation of his system by flashing more than 1,000 words from a moving steamer to the receiving station at Navesink, and the subsequent recognition he received from our government, may be recalled in this connection.

The present status of wireless telegraphy and what has been accomplished may be summarized as follows: Accepting the results bequeathed him by previous investigators, Marconi overcame the difficulties in the way one by one. First, after perfecting his transmitting and receiving apparatus, he surmounted the opposition offered by damp air, clouds, fogs, etc. Then came the apparent difficulty presented by the curvature of the earth. Instead of adopting the conclusion that the waves might follow a course parallel to the earth's curvature, he surmised that for every square of a certain distance the "receiver" must be fixed at a corresponding distance above the earth. He himself has disproved this by his latest achievement in telegraphing 60 miles with the "receiver" only four feet from the ground. Many of his experiments have been conducted on or near the coast, as it was found they were more uniformly successful at the level of the sea. In fact, the greatest benefits promise to accrue in connection with maritime affairs, as, for instance, the connecting of isolated lighthouses and the equipment of vessels with apparatus for instant communication with the shore and with each other at a distance, etc. At least one wreck was obviated by the use of wireless telegraphy, thereby forcing from the French government its reluctant consent - previously withheld - to the establishment of a station on its coast for Marconi's celebrated channel experiments. In South Africa the wireless system was successfully used during the Boer-British war, islands in the Hawaiian group have been placed in communication with each other, France and England converse through ethereal space, and at present there seems no insuperable obstacle to transoceanic communication between Europe and America.