Nikola Tesla Articles

Wardenclyffe - A Forfeited Dream

In mid-January, 1900, Nikola Tesla returned to New York City after spending eight months and $100,000 building an electrical research experimental station at Colorado Springs. There, in the shadow of Pike's Peak, he produced the greatest point-to-point electric discharge ever achieved by man — sparks 100 feet in length. He spoke of attempting to communicate with Mars, and of sending power to ships at sea. The scientific fraternity, jarred by reports of his receiving "signals" of extraterrestrial origin those dark cold nights in Colorado snapped, "If Tesla really has something, let him demonstrate it out in the open for all to witness."

With successful completion of experiments and a rapidly growing list of radio patents, Tesla felt he was riding the crest of a new technology. He envisioned a world radio center comprising all the artifices that we now have today — interconnected radio-telephone networks, synchronized time signals, instantaneous stock reports, pocket receivers, private communications, press radio service — or, in his words, a World System of intelligence transmission.

During the past year Marconi had succeeded in transmitting signals across the English Channel. Tests were being made by experimenters here to signal the results of yacht races on Long Island Sound. To have significant impact, it was quite obvious to Tesla that a demonstration of his system must be sensational and, moreover, readily understood by the public to whom he constantly appealed through a sympathetic press. What could be more impressive than operating his recently patented radio controlled boat at the Paris Exposition from his office in New York?

Tesla asked Robert Underwood Johnson, poet, author, and editor of the noted literary magazine Century to publish an extensive article on the philosophical aspects of energy sources and use. It appeared June, 1900, with amazing photographs taken at the Colorado Springs experimental station, hopefully attracting new research and development capital. When first meeting Tesla in 1894, Johnson was stirred by his genius and resolved to aid him in every way possible. He wrote to his good friend at Yale, urging an honorary degree for Tesla, and within a few weeks the necessary arrangements had been completed for ceremonies that academic year.

Anxious to renew the social whirl that he had not enjoyed since leaving for Colorado, Tesla sought out his friends at The Players club in Gramercy Park where Johnson had introduced him. The club had been remodeled by the eminent architect Stanford White who, with other men of arts and letters, were awed by Tesla's portrayal of future developments at hand. Known for stagey performances at his laboratory in the evenings, he had quickly become lionized by the "Four Hundred." His table at Delmonico's and the Waldorf-Astoria Palm Garden where he lived again became a favorite meeting place.

As a free inventor, Tesla's sources of income were royalties from inventions and working capital obtained from men of private indulgence who were impressed with Tesla's record of accomplishment. They were also assured by the ease with which he held his priority in patent litigation despite the constant attempts to break the monopoly he maintained for the Westinghouse Company. Tesla therefore went to his friends with a plan readily appreciated in terms of return-on-investment. The idea was to outperform the Atlantic Cable, not only in speed but in capacity with many simultaneous messages.

He talked of his far-reaching plans to John Jacob Astor, Thomas Fortune Ryan, and other men of means. Spending money he didn't have, he lavished gifts on his friends in such manner as sending a special messenger all the way to Newport, Rhode Island, with a cabochon sapphire ring, a wedding gift to Henry O. Havemeyer.

But it was late in November when his plan caught the attention of J. P. Morgan. Tesla asked for $100,000 to erect a plant in less than a year's time to transmit messages across the Atlantic. In two weeks he had $150,000 from Morgan, and the enormity of the project was then full upon him. He must work swiftly to complete the electrical design so that the special equipment could be ordered. Land must be acquired, and an architect engaged.

By March of the following year he went to Pittsburgh and placed a contract with the Westinghouse Electric Company for generators and transformers. As a site for the World System, Tesla found it in the name of James S. Warden, director of the Suffolk County Land Company. It was a remote wooded parcel adjacent to the Jemima Randall and George Hegeman farms at Shoreham, L. I., 65 miles from Brooklyn. The site was named "Wardenclyffe."

Meanwhile, Tesla engaged agents in Britain to locate a suitable site for a station on that coast. The Paris Exposition had come and gone, and with it the chance for a spectacular public demonstration of radio control from New York, but surely commercial radio communication with Britain would have a greater impact.

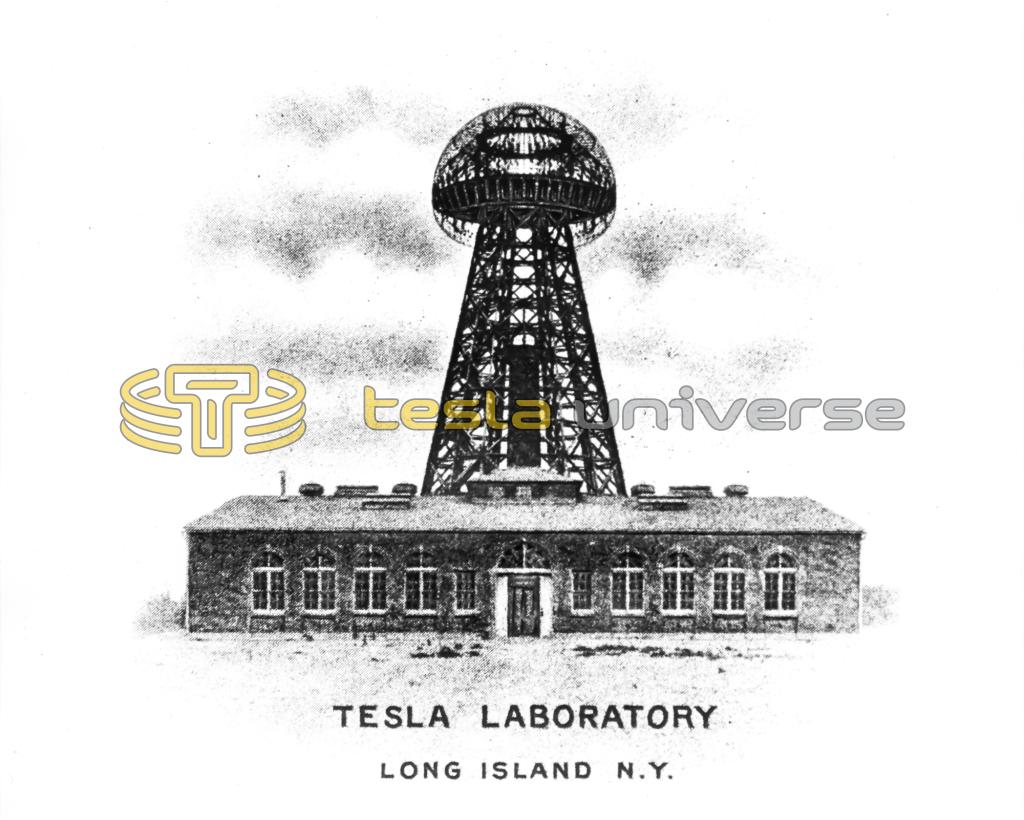

Stanford White, who with others had caught the excitement of the grand plan, anxiously undertook the design of the principal building. The transmission tower was designed by W. D. Crow, an associate of White. It was contemplated that four or five other buildings would be constructed and a large number of houses to accommodate the several hundred people who would be employed.

In the Summer of 1901 the townspeople of Shoreham believed they were on the brink of prosperity as they watched the activity of the building crews. Progress was supervised closely by Tesla who lodged at the nearby De Witt Bailey home for several days at a time. Within a few months the large brick building had taken form and foundations for the majestic octagonal tower begun. The tower was being constructed entirely of large wood beams assembled on the ground and hoisted into position. It would rise to a height of 187 feet.

Below the tower a well had been dug 120 feet deep and twelve feet square, lined with eight inch timbers. A spiral stairway encircled a telescopic steel shaft that would rise by air pressure 300 feet to contact the tower's top platform.

By November the steam boilers and engines had arrived and were being installed. Wardenclyffe was only 1½ hours away by fast train and, with his staff directed by George Scherff, legal secretary and personal confidant, Tesla felt he could now spend more time in the city. The project continued under tight control — Letters or telegrams arrived nearly every day, sometimes as many as three carrying detailed instructions and addressed to George Scherff, c/o "The Tesla Works, Wardenclyffe."

Owing to a variety of unforeseen causes, exasperating delays in the delivery of electrical equipment were beginning to try Tesla's patience. The year 1901 was drawing to a close and newspapers suddenly announced that Marconi signalled the letter "S" across the Atlantic from Cornwall, England, to Newfoundland on December 12. This was accomplished with devices in no manner approaching the magnitude of operations Tesla was establishing at Wardenclyffe. Why, then, did Tesla require such an effort?

The reason for secrecy is now clear. The Wardenclyffe plant was not to be solely used for the transmission of signals across the Atlantic, but more ambitiously, the transmission of electric power to any point on the globe without wires — a dream that Tesla had been constantly working toward for the past ten years. With his tower, he would "wobble" the Earth's static charge. A successful test of his thesis would indeed be the crowning achievement of the age.

In June, 1902, he found it desirable to move his laboratory from the city. The city laboratory had been a mecca for scientists from all over the world and at the same time a rendezvous for inquisitive reporters. Wardenclyffe provided the seclusion and quiet more in keeping with his desire for secrecy about new avenues of investigation. But it was not entirely out of reach, and Tesla gave strict orders to Scherff that no details of the project were to be disclosed and no one other than his workers be permitted on the premises.

Early in 1903 the 55-ton, 68-foot spherical rib-cage dome on top of the tower was nearing completion. It was eventually intended to enclose the cage with copper plates so that an insulated metal ball would be formed. From afar, the tower had the appearance of a huge mushroom rising above the trees along the North Shore. It could easily be seen from New Haven across the Sound.

George Scherff cautioned Tesla that funds were getting dangerously low, and that creditors would soon be pressing him on outstanding accounts. Substantially more investments would be needed to complete the project. Tesla wrote to Morgan about the frustrating delays he had suffered during the course of the project saying in part,

April 8, 1903

". . . you have raised great waves in the industrial world and some have struck my little boat. Prices have gone up in consequence twice, perhaps three times higher than they were. . ."

Morgan was not agreeable to advancing additional funds.

April 22, 1903

". . . You have extended me a noble help at a time when Edison, Marconi, Pupin, Fleming, and many others openly ridiculed my undertaking and declared its success impossible. . ."

No change in Morgan's position. Tesla must now be candid to the point that his true aim was a mark much higher than that originally presented — that is, the wireless transmission of power.

July 3, 1903

". . . If I would have told you such as this before, you would have fired me out of your office. . . Will you help me or let my great work — almost complete — go to pots? . . ."

The answer —

July 14, 1903

N. Tesla, Esq.

"I have received your letter . . . and in reply would say that I should not feel disposed at present to make any further advances."

J. P. Morgan

With such a reply from Morgan he left for the solace of his laboratory to conduct preliminary tests. That night, and for several succeeding nights, the residents of Shoreham were astonished to see lightning-like flashes emanating from the tower. At times the air was filled with blinding streaks which seemed to shoot off into the darkness on some mysterious errand. When questioned about them the following day, neither Tesla nor his workers would give any explanation.

The fall of 1903 saw the onset of the "Rich Man's Panic," an aggravation which compounded Tesla's problem of securing investment capital. Although successful in obtaining help from Thomas Fortune Ryan, who agreed to provide supplemental investment funds, these were used to pay an existing mountain of debts, with no excess for completion of the World System project. Tesla exclaimed, "My enemies have been so successful in representing me as a poet and visionary, that it is absolutely imperative for me to put out something commercial without delay." So, to obtain other needed investments, he issued two brochures — The World System, and another handsome manifesto prepared on vellum which announced his intention of entering into the field of consulting engineership. He wrote to George Scherff, "I swear! If I ever get out of this hole nobody will catch me without cash."

Most damaging of all, a whispering campaign had begun. "If Tesla's plan is such a good thing, why does not Morgan see it through? He is the very last man to let a good thing go." There just did not seem to be enough sources of ready cash to keep his Wardenclyffe project going together with his other researches. Meeting his fixed obligations was a dilemma.

On May 4, 1905, the fundamental patents on alternating current motors and electric power transmission which he had sold to the Westinghouse Company expired. This was the end of royalty payments from a source branded as the "Patent Pool Trust" and likened to the telephone patents. He suddenly did not even have enough money to buy a carload of coal to fire up the boilers in the laboratory. He wrote to Scherff, "The troubles and dangers are at their height. Coal problem still awaits solution. The Wardenclyffe specters are hounding me day and night. . . When will it end?"

Notice was then received by Tesla from Colorado Springs that a suit had been instituted against him for non-payment of electricity furnished to his experimental station in 1899. Earlier, the city had sent a bill for water furnished the station. In his novel reply he said that inasmuch as he had graced that city with his presence and had erected an experimental station there, he believed that the city should donate all the water used! The power company was not so kindly disposed of its services and Tesla ordered that the station should be sold for value of lumber. At the same time another notice was received that the caretaker at his laboratory there was bringing suit for unpaid balance of wages due. In September, Tesla appeared in Colorado Springs County Court with his attorney to answer the suit. Inexorably, judgment was awarded in behalf of the plaintiff for approximately $1000, satisfied in-part by a Sheriff's sale of his laboratory fixtures and by $30 payments dragging over the next half-dozen years for the balance.

Although Tesla was beginning to secure money from various sources as speculation on inventions, for the most part it was applied to long standing obligations. Loans were secured for current efforts concentrated in two areas. First, to get something commercial on the market to shore up his reputation. He set up a small assembly operation at his Wardenclyffe laboratory to make small Tesla coils for which there was a demand by medical offices, research laboratories, and radio experimenters. Next, a new invention which appeared to be a beautiful solution to many mechanical problems — a turbine of ideal simplicity, reversible, and capable of developing enormous torque. In speaking of it he stated, "I am looking for a revolution in mechanics from the application of this principle." The turbine was never developed commercially because, like so many of Tesla's inventions, it was years ahead of its time. A revival of interest has occurred in recent years as a result of the development of superior metals.

June 25, 1906, the papers were full of the death of Wardenclyffe designer Stanford White — murdered on the roof of Madison Square Garden by Harry K. Thaw, a Pittsburgh financier. White was shot three times in clear view of New York's prominent socialites, the victim of a fictionalized triangle involving Thaw's wife, Evelyn Nesbit. Thaw was committed to Matteawan Hospital for the Criminally Insane the following year. New York today abounds with magnificent edifices to his memory including the Astor mansion at Rhinebeck, the Hall of Fame at New York University, Madison Square Presbyterian Church, and the Garden City Hotel.

In the fall it became painfully disappointing to Tesla that it would be necessary for George Scherff to find other means of employment. Scherff was more important in the successes that Tesla achieved than has been realized by biographers. His steadfastness to Tesla is in retrospect a shining medal. After Scherff did find other employment he continued, whenever possible, to help Tesla keep his financial affairs in order. He did this evenings and weekends until just prior to Tesla's death. Thousands of dollars of Scherff's own money went into various Tesla enterprises that did not succeed, but Scherff always most enthusiastically looked to the day, just ahead, when Tesla's ship would come in. Certainly, without someone as Scherff to maintain Tesla's legal records and accounts after the turn of the century, he would have drowned in a stormy financial sea.

Then, as if vanishing in the night, Tesla and his staff departed from Wardenclyffe. Even Thomas R. Bayles, the general passenger agent of the railroad station just across the road from the laboratory, was unaware of the abandonment. Again, Shoreham became a place where a passenger alighted only occasionally. Some of the farmers who came to Shoreham to send their products to the city looked at Tesla's tower and shook their heads sadly. "The breeze at the top is something grand in Summer evening," they said. A fine view of ocean steamers could be seen across the flat neck of the island at that point.

When it became generally known that the Wardenclyffe operation had closed, an occasional research engineer bitten with curiosity would make his way out to the laboratory. If the caretaker was still there, the visitor would be admitted for a tour of the laboratory. What he would behold was something quite beyond his expectations — intricate mechanical mechanisms, glass blowing equipment, a complete machine shop including eight lathes, X-Ray devices, many varieties of high frequency (Tesla) coils, a radio controlled boat, exhibit cases with at least a thousand bulbs and tubes, an instrument room, electrical generators and transformers, wire, cable, library and office. A strange stillness filled the building. It seemed as if it were a holiday, and the workday tomorrow would bring back all the workers to their assignments. A walk outside to the tower and up the flights of stairs — soon one caught the whisper of the wind through the spars. One believed he could perceive muted voices and clanking sounds below. But the switch had not been thrown. The dynamos stood idle.

In 1912, Westinghouse, Church, Kerr & Company obtained a judgment against Tesla for $23,500 for machinery furnished at Wardenclyffe. The equipment was subsequently removed. In order to keep a roof over his head, Tesla had given two mortgages on Wardenclyffe to George C. Boldt, proprietor of the Waldorf-Astoria, to secure payment of hotel bills amounting to $20,000. Tesla requested that they not be recorded fearing that all his project's would be destroyed if the matter became public. He was unable to make any payments at all, and in 1915 he turned the Wardenclyffe deed over to Waldorf-Astoria, Inc., through a silent intermediary.

In noting the passing of the property from Tesla's hands, the Brooklyn Eagle of March 26, 1916, commented: "Aside from the scientific interest which attaches itself to the place because of its association with the work of Nikola Tesla, a more romantic local interest has always surrounded the place. It is not too much to say that the place has often been viewed in the same light as the people of a few centuries ago viewed the dens of the alchemists or the still more ancient wells of the sorcerers. An atmosphere of mystery hung over the place, an unearthly influence seemed to be radiated from the alembic topped tower, as if drawn down from interstellar space and spread over the countryside to inspire wonder and awe in the minds of the nearby farmers and villagers. . ."

The Waldorf-Astoria attempted to convert the property to cash in various ways but the improvement structures, uniquely designed for wireless power transmission, had little conversion value. The War Department was approached without success in connection with the activities at Camp Upton near Yaphank (now the site of Brookhaven National Laboratory). An abortive offer was received to establish a pickle factory there.

With no promising offers in two years, a salvage contract was taken by the Smiley Steel Company of New York to remove the tower. Under the supervision of Wm. H. Glancey of Shoreham, it was set with dynamite on July 4, 1917. One of the crowd that gathered spoke for most of them — "Alas! A dream broken." Bets were placed by others whether it would be down by nightfall. It was still standing that weekend, and the job took until the next holiday — Labor Day. Only $1750 was realized above demolition costs.

Tesla was not in New York when the tower finally came down. He had been engaged by a Chicago firm as consulting engineer for a development program of his spiral-flow turbine. Imagined stories were given exaggerated play in all the New York papers that the tower had been destroyed by order of the government to prevent its use by foreign agents. No basis in fact supports these stories and would not have been given encouragement if the Waldorf-Astoria legal action had been made public. Moreover, an expert rigger for the salvage firm feared to scale the tower more than half way. The stairs had fallen and many wood members were rotted out.

In 1925 the property was acquired by Walter L. Johnson of Brooklyn. Through the untiring efforts of Mrs. Sadie E. Robinson, Shoreham booster and agent for Johnson, the property was purchased on March 6, 1939, by Plantacres, Inc., and leased to the corporate predecessor of Peerless Photo Products, Inc. The firm today occupies fifteen acres of the original tract owned by Tesla for research and production of photosensitive materials.

When the grandiose plan of wireless power transmission was finally out of reach for Tesla he wrote: "It is not a dream, it is a simple feat of scientific electrical engineering, only expensive — blind, faint- hearted, doubting world! . . . Humanity is not yet sufficiently advanced to be willingly led by the discoverer's keen searching sense. But who knows? Perhaps it is better in this present world of ours that a revolutionary idea or invention instead of being helped and patted, be hampered and ill-treated in its adolescence — by want of means, by selfish interest, pedantry, stupidity and ignorance; that it be attacked and stifled; that it pass through bitter trials and tribulations, through the strife of commercial existence. So do we get our light. So all that was great in the past was ridiculed, condemned, combatted, suppressed — only to emerge all the more powerfully, all the more triumphantly from the struggle."

WARDENCLYFFE

On February 14, 1967, the Brookhaven Town Historical Trust was established to preserve and maintain areas, sites, buildings and objects relating to the history and culture of the Town of Brookhaven. The Trust is administered by a Board of Trustees and is a nonprofit, public benefit corporation. It is the first historic trust in the United States to be administered and operated by a municipality. The resolution to create the Trust was offered by Councilman Robert E. Reid. A research committee appointed by Brookhaven Town Supervisor Charles W. Barraud selected the Tesla laboratory designed by architect Stanford White as the first site. The building is currently owned by Peerless Photo Products, Inc., and is recognized as an historic site through the interest and cooperation of its President, Edgar A. Kniffin. It is fitting that the access road to the Peerless plant was named Tesla Street years ago by the Town Board.

Supervisor Barraud has indicated that this is the first of many historical locations scattered throughout the town that will be surveyed for possible designation as historic sites, in the hope that these will be preserved and their important contributions to society recognized.

For the preparation of this historical review the author acknowledges with special thanks assistance received from: David C. Mearns and John C. Broderick, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Davis Erhardt, Long Island Division, Queens Borough Public Library, Jamaica, N. Y.; Thomas R. Bayles, Middle Island, Long Island, N. Y.