Nikola Tesla Documents

Nikola Tesla FBI Files - Page 140

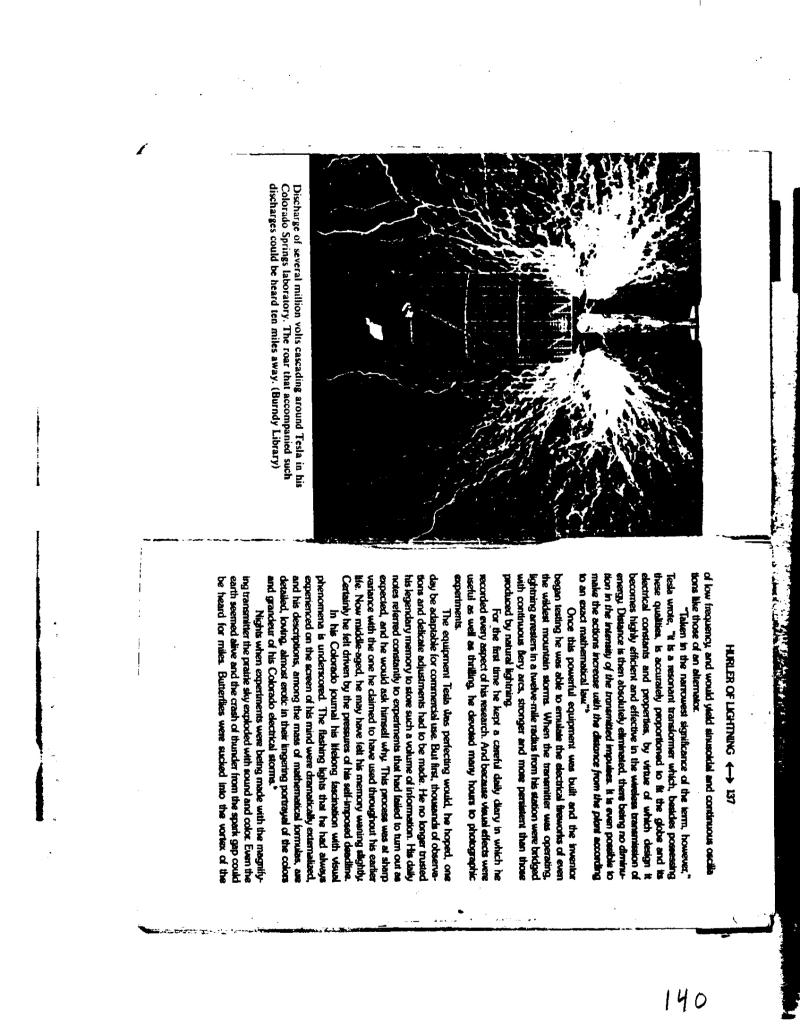

Discharge of several million volts cascading around Tesla in his Colorado Springs laboratory. The roar that accompanied such discharges could be heard ten miles away. (Burndy Library) HURLER OF LIGHTNING ←→→ 137 of low frequency, and would yield sinusoidal and continuous oscilla tions like those of an alternator. "Taken in the narrowest significance of the term, however," Tesla wrote, "it is a resonant transformer which, besides possessing these qualities, is accurately proportioned to fit the globe and its electrical constants and properties, by virtue of which design it becomes highly efficient and effective in the wireless transmission of energy Distance is then absolutely eliminated, there being no diminution in the intensity of the transmitted impulses. It is even possible to make the actions increase with the distance from the plant according to an exact mathematical law" Once this powerful equipment was built and the inventor began testing he was able to emulate the electrical fireworks of even the wildest mountain storms. When the transmitter was operating, lightning arresters in a twelve-mile radius from his station were bridged with continuous Bery arcs, stronger and more persistent than those produced by natural lightning. For the first time he kept a careful daily diary in which he recorded every aspect of his research. And because visual effects were useful as well as thrilling, he devoted many hours to photographic experiments. The equipment Tesla was perfecting would, he hoped, one day be adaptable for commercial use. But first, thousands of observations and delicate adjustments had to be made. He no longer trusted his legendary memory to store such a volume of information. His daily notes referred constantly to experiments that had failed to turn out as expected, and he would ask himself why. This process was at sharp variance with the one he claimed to have used throughout his earlier life. Now middle-aged, he may have felt his memory waning slightly. Certainly he felt driven by the pressures of his self-imposed deadline. In his Colorado journal his lifelong fascination with visual phenomena is underscored. The flashing lights that he had always experienced on the screen of his mind were dramatically externalized, and his descriptions, among the mass of mathematical formulas, are detailed, loving, almost erotic in their lingering portrayal of the colors and grandeur of his Colorado electrical storms.* Nights when experiments were being made with the magnifying transmitter the prairie sky exploded with sound and color. Even the earth seemed alive and the crash of thunder from the spark gap could be heard for miles. Butterflies were sucked into the vortex of the 140