Nikola Tesla Articles

All the World in Instant Touch

Tesla's Greatest Idea Is Ready for a Practical Test.

MESSAGES BUT NO WIRES.

Twenty Miles the Limit Now, but His New Machine May Reach the Antipodes.

THE STARS NOT OUT OF REACH.

Electrical Energy Will Be Much Cheaper with No Costly Wiring Needed.

LIGHT THAT RIVALS THE SUN.

Garrett P. Serviss Discusses the Famous Electrician's Marvelous Inventions.

Mr. Nikola Tesla has anticipated the twentieth century by telegraphing without wires. He has transmitted electric signals through the earth a distance of twenty miles and received similar signals in return.

He believes that the system he has just perfected will render it possible to communicate Intelligence from any point on the globe to any other point without the intervention of wires or connecting lines of any kind.

At present only a beginning has been made, but the principle is established, and when the details have all been worked out it may be that greater distances than those which separate the different quarters of the earth will prove to be traversable by electric vibrations under the control of human intelligence.

If a message can be sent around the earth without wires or cables, it may possibly be sent from the earth to the moon or to Venus or to Mars.

All this, however, is for the future. At present it is enough to know that such messages have actually been transmitted a distance as great as from New York to Menlo Park.

The details of his method have not yet been made public by Mr. Tesla, but his experiments with high frequency electric currents and the wonderful results he has attained in the production of light without wires have prepared the public as well as the world of science for some such announcement as that which now comes concerning the new system of telegraphy.

How eagerly and expectantly men of science have been peering in the direction of this great discovery is well shown by some remarks made by an English authority, Prof. W. E. Ayrton, in recent lecture in London.

He was speaking particularly of marine telegraphy and of the difficulties at present encountered in connecting the continents by wire.

"But there is no doubt," he said. "that the day will come, may be when you and I are forgotten, when copper wires, gutta-percha coverings and iron sheathings will be relegated to the museum of antiquities.

Then when a person wants to telegraph to a friend, he knows not where, he will call in an electro-magnetic voice which will be heard loud by him who has the electro-magnetic ear, but will be silent to every one else.

"He will call 'Where are you?' and the reply will come loud to the man with the electro-magnetic ear; 'I am at the bottom of the coal mine, or crossing the Andes, or in the middle of the Pacific.'

"Or perhaps no voice will come at all, and he may then expect the friend is dead. Think what that will mean. Think of the calling which goes on from room to room, then think of that calling when it extends from pole to pole — a, calling quite audible to him who wants to hear, absolutely silent to him who does not."

The ink that printed the report of Prof. Ayrton's lecture was not yet dry when Mr. Tesla had begun the accomplishment of the scientific miracle which the lecturer described.

Indeed, probably before the lecture was composed on one side of the Atlantic the feat had been done on the other side.

For Prof. Ayrton's "electro-magnetic voice" put one of Mr. Tesla's electric oscillators, and for his "electro-magnetic ear" one of Mr. Tesla's electric receivers, and practically you have what was in London a mere dream of the scientific imagination transmitted in New York into a dazzling scientific fact.

Astounding as this discovery seems, many things have heretofore shown clearly that it was coming, but few probably expected that it would come so soon.

How rapidly it will be developed will depend upon the possibility of increasing the energy of the impulses sent out through the ether and of improving and perfecting the devices for their reception.

But if a message of this kind can be transmitted twenty miles to-day there is reason to hope that it may be transmitted across the sea or the continent before the end of the century.

GARRETT P. SERVISS.

TESLA TELLS THE STORY.

Will Make the Earth Vibrate to a Signal Code and Furnish Light Without Filaments.

Nikola Tesla announces that he has so nearly perfected three of his wonderful discoveries that he will soon be ready to put them to a practical test.

One, of which he had given some hint before, is a machine which will set the whole earth in vibration.

These vibrations, set to the measures of an international code, may be read at any part of the earth, thus making possible communication, without wires, between any place and its antipode.

Then he has so improved his electrical oscillator that he is able to produce from a glass tube, without the usual filament of the incandescent lamp, a white light, in which only 30 per cent of the electrical energy will be expended in heat, instead of 97 per cent., as in the Incandescent light.

And last, though by no means least, he fully believes he will be able to transmit electrical power from place to place without the use of wires.

"I have so improved my machine," he says, "that I am able to transmit signals through the earth for a distance of twenty miles. I am now at work on another which will not be hampered or affected by any distance, even though it be half around the globe.

"But, more, the transmission or signals in this manner is not the only result I have arrived at, although it was the only end I had in view.

"I have been able to substantiate the principle, that it is a possibility to send electrical energy from one point to another without wires."

Think, for a moment, of the immense advantage of knowing instantly what is going on in all the commercial centres of the world; of being informed at once of any international embroglio which may affect the business interests of the whole globe.

Every city in the world would be a station on an immense ticker circuit, and important news would go from one part of the world to the other with the rapidity of a lightning flash.

Imagine, if you will, an immense rubber bag flied with water. At one point a tube is inserted and in this tube is a piston. Press on the piston rod and the incompressible water expands the rubber bag.

Withdraw the piston and the bag shrinks just as much as there is water drawn into the tube. Now place in the rubber another tube with a piston. At every pressure on the first piston the effect will be felt and measured in the second tube.

Let a certain action of one piston dictate a word or a sentence; watch the other piston and you may read it.

This illustrates the principle upon which Tesla bases his idea of telegraphing through the earth. The qualities of electricity are inertia, incompressibility and elasticity.

He decided, after investigation, that if the electro-static condition of the earth could be disturbed in one place, the disturbance would be felt all over earth.

Then, if this disturbance was created by a machine, any similar machine, at any other point, should be susceptible to the disturbance.

What then, he argues, is necessary other than to have each degree of disturbance accord with a code signal, regulate the disturbance so as to send any message you wish, and, at all other places where there are similar machines the message will be recorded.

The idea first occurred to Tesla when he was putting up a telephone system in Budapest. Two miles away was a Morse telegraph cable, and on the telephone wire every message that went over the cable could be heard.

Although the telephone wire and the cable were grounded the communication was by Induction.

Tesla devoted himself to the idea, occasionally speaking about it. He received little encouragement until he was at the Chicago Exposition, and Prof. Helmholz, the greatest electrician of the century, called on him. To him Tesla outlined his plan. The professor thought for a minute and then said:

"Yes, I think you can do it. The great obstruction, however, is that you will require such enormous power."

Even then Tesla had in mind a machine which, he felt assured, would remove that obstruction. It is this machine he has perfected.

Just what it is like he declines to say, but inasmuch as at the time of his talk with Prof. Helmholz he was developing his electric oscillators that he might substantiate his claim that light might be produced from tubes it is belleved the oscillator is the machine.

It is a producer of wonderful vibrations, Tesla claiming he can get 50,000,000 vibrations a second. He exhibited one yesterday which, he said, developed 800,000 vibrations a second.

More than probable it is that by means of the application of one of these oscillators to the static electricity in the earth he hopes to produce the disturbances without employing a remarkable amount of power.

With one of these oscillators Tesla has caused a bar of steel one inch thick to vibrate with such rapidity that literally it has shaken itself to pieces, a fragment falling from one end, a second from the other and so on. In the same way he has shattered a ring of steel four inches wide.

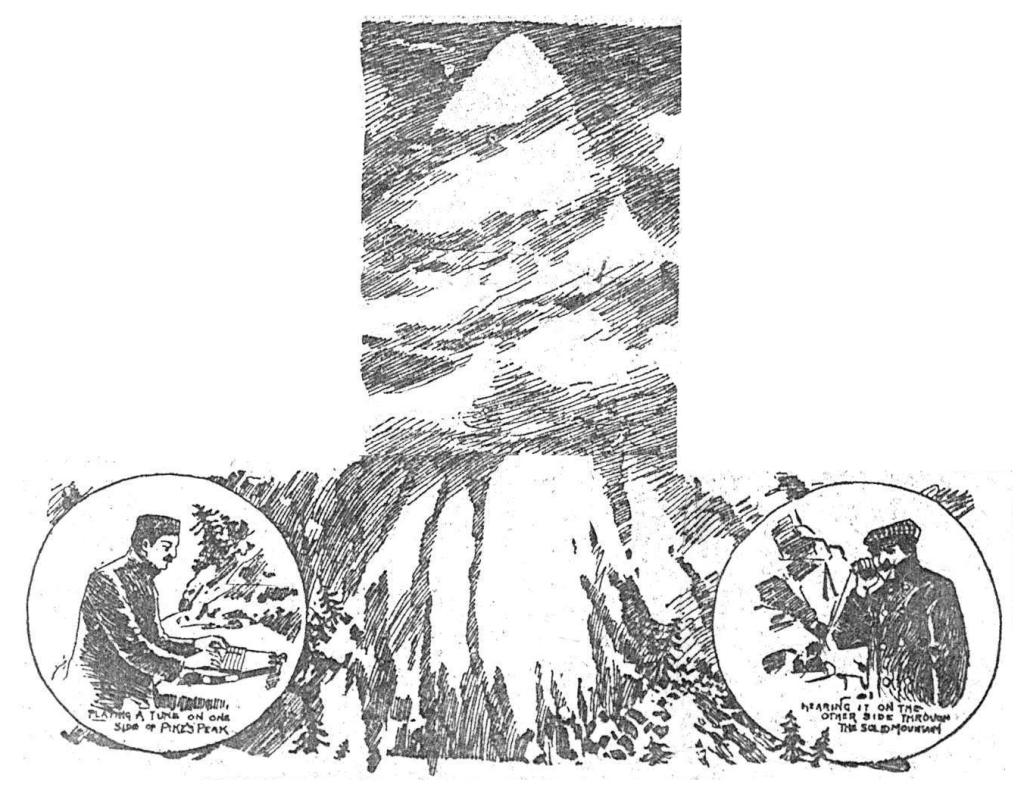

"What experiments have you made in the transmission of signals by this apparatus?" he was asked.

"I have one that I know will operate over a distance of twenty miles. What more do I need? I know my best machine will do all I require of it.

"If I have a machine that will throw a stone five feet it is not necessary for me to construct another before I can know the stone may be thrown ten feet. All that is necessary is that I thoroughly understand the motive power, and from that I can tell."

"In what way will your discovery be applied ?"

"There might be one in every large city in the world operated by an international agreement so that all public news might be known instantly in every country.

"It would put every important point in the world in instant touch with every other. Millions of these stations might be established.

"No. I do not think it will do away with the telegraph lines or the cables, for it would be almost impossible to use these machines to filter all the news to the public.

"To my mind it will increase the business of the telegraph and cable companies.

"I feel it will be a great boon to humanity. To my mind it will avoid wars, will prevent panics and will enlist the sympathies of all the rest of the world for any section that may be in distress.

"This may be only a dream, but I feel that if we are ever to communicate with the stars it will be by this method and this only."

There are wonderful commercial opportunities in this discovery made by Tesla as to the transmission of electrical power from point to point without wires.

It makes possible the erection of one central station, from which power can be sent wherever needed at a cost greatly below what is charged at present, for the copper feeding wires which are now used to transmit power the central station are the heaviest of expense.

When the question of motive power for the underground road was under consideration by the Rapid Transit Commission and electricity was advocated it was stated that the cost of the feeding wires alone for the underground line would be $7,000,000.

Could the electrical power produced at Niagara Falls be distributed without wires the cost would be so lessened that many more persons could avail themselves of the power, and the same condition might have its effect in the report of the commission which has just examined the Falls of the Nile, with a view to their adaptability to the production of electrical energy.

Factories and large workshops where electricity is employed, distributed among the various rooms by wire, would be operated at a greatly reduced expense; railroads would do away with their costly trolleys, and in every branch of trade where the electric fluid plays its part the outlay would be decreased.

No idea as to how he will accomplish this wireless transmission could be gained from Inventor Tesla, but it may be guessed that his oscillators will be brought into play in the development of his plan.

They are the important factor in the production of the new white light he has invented.

"I can safely say now," he declared, "that from tubes a white light can be produced at a cost which is at least comparable to that of other light, and easily within the reach of all."

He picked up a Crookes tubes and placed it near the points of an oscillator, which developed 800,000 vibrations a second.

Instead of the phosphorescent glow usually produced from the tubes, a white light, wonderfully diffusive, was given out, even though the sunlight was streaming in through the windows.

The muscles of Tesla's arm contracted as the contact was first made.

"That was a voltage of 20,000." he said, as he put away the tube, "and it entered my body, as you saw."

The difficulty of producing such light heretofore was that its cost, because of the electrical energy required, was nearly ten times as great as that of the incandescent lamps.

With the oscillators it is different, however. They give the required energy and at a reduced cost.

"This light," said Tesla, "is not so brilliant as to be of a high candle power, yet it is very diffusive and will fill a room with a beautiful illumination. By the way, we have always accustomed our eyes to a light that is too brilliant.

"While in the Incandescent lamp more than 96 per cent. of the power is expended in heat, I have got as much as 60 per cent. of light out of one of these the tubes. But of course such an amount is not practical.

"I have also another tube, which, taking its energy from the oscillator, is brighter than any arc light by ten times, and makes a wonderful searchlight not to be compared to any that are in use. It is really like the sun."

Regarding the application of these tubes to houses Tesla said it would be done ordinarily with wires through each room, though where this was impossible the light could be produced without wires.

EDISON POOH-POOHS IT.

Nikola Tesla's Announcement Is Incomprehensible to the Wizard of Menlo Park.

Thomas A. Edison smiled when a World reporter asked for his views of Tesla's claims. "I don't find anything in them for discussion," said he. "It is all incomprehensible to me. He does not tell of anything accomplished. There is nothing that I can grasp, no facts that form even a basis of discussion.

"I have done something in the general field of work suggested by Mr. Tesla's claims, but I left it when I found that it was not profitable or practicable.

"For instance, a few years ago we succeeded in telegraphing from a moving train of cars to a terminal station or to another train. We could throw a current over the train, and by a simple apparatus. The entire plant would cost only $150. The process was fully described in the newspapers at the time.

"It was never of any practical value, aside from locating work trains along the road. We also showed that a current could be transmitted from one kite to another in the air.

"It might be possible," Mr. Edison' said, with a smile, to send a wave to England by the use of 5,000,000 or 6,000,000 horse-power, a wave that would transmit a letter, and it might be possible to transmit twenty waves or a word a day. The power required would be enormous. No, I can see nothing in this scheme described in such a vague, uncertain way."