Nikola Tesla Articles

Appraisement of Estate Reveals Astor's Personality

Interesting Sidelights Thrown on the Character of Victim of the Titanic Disaster by the Record of His Effects. Comparatively Modest in His Personal Luxuries, an Inventor and a Good Investor.

The appraiser's report of the estate of Col. John Jacob Astor, filed in the Surrogate's Office last Monday, throws a flood of light on a great American fortune in a way which can hardly be paralleled in court records of the sort. The dimensions of this fortune of $87,000,000 and over, the importance to New York City of the Astor real estate holdings, the intricate system of trusts and a fabric of family tradition which amounts to a rule of primogeniture among the Astors for five generations, and the picturesque interest attaching to Col. Astor and his stripling heir excited public attention and found a response in elaborate newspaper reports of the appraisal. Yet these reviews, owing to the intricacy of the subject, could not touch upon details which, when segregated and analyzed, form a fascinating character study of the man whose enjoyment of these millions ended with the Titanic disaster. John Jacob Astor seemed to be an obvious personality to those who read of the appraiser's report. The obvious was most deceptive. Behind the summary of millions lurked another man, neophilosopher and mystic, bound as completely by family tradition as some Spanish princeling of simple tastes, though with surroundings that might be called regal - a man who could have been a scientist if he had been given a chance - the excuse of the poor inventor becoming, in this case, that of the multi-millionaire.

Such is the story told in legal documents which seem to be, at first glance, as dry as dust, though found on closer scrutiny to embody a unique human document.

The simplicity of Col. Astor's personal, intimate surroundings is one of the most forceful impressions gathered from the appraisal. With a fortune of more than $87,000,000 and an income estimated at not less than $3,000,000 a year, his immediate belongings, including wearing apparel, jewelry and dressing requisites, did not foot up to more than $10,829.

At Ferncliff, his estate on the Hudson, Col. Astor slept in a room that could be furnished for $1,625, in an enameled bed appraised at $85. He walked on a $75 carpet, looked from walls ornamented with pictures worth $35 to the most costly ornament of the room, a "grandfather's clock," appraised at $185. All of his apparel, desk and toilet utensils and other personal effects at Ferncliff, said the appraisers, could be duplicated for $412.

No Pomp in His Rooms

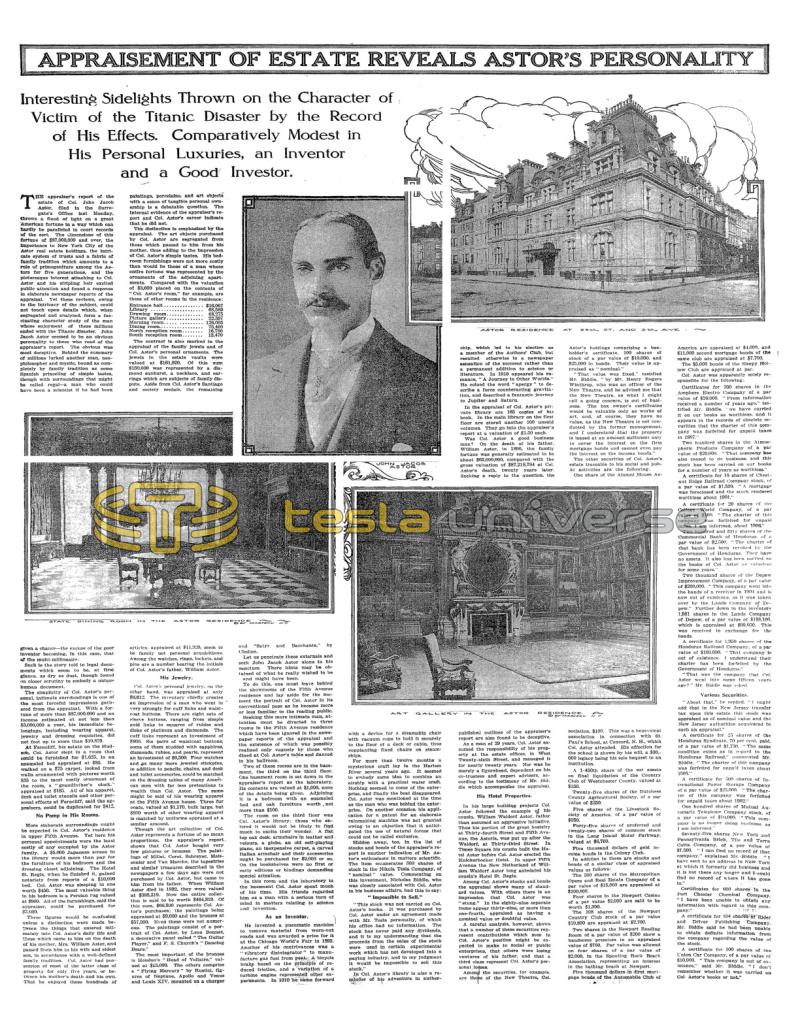

More elaborate surroundings might be expected in Col. Astor's residence in upper Fifth Avenue. Yet here his personal appointments were the least costly of any occupied by the Astor family. A $5,000 Japanese screen in the library would more than pay for the furniture of his bedroom and the dressing closet adjoining. The Hotel St. Regis, when he finished it, gained notoriety from reports of a $10,000 bed. Col. Astor was sleeping in one worth $450. The most valuable thing in his bedroom is a Persian rug valued at $900. All of the furnishings, said the appraiser, could be purchased for $3,609.

These figures would be confusing unless a distinction were made between the things that entered intimately into Col. Astor's daily life and those which came to him on the death of his mother, Mrs. William Astor, and passed from him to his wife and eldest son, in accordance with a well-defined family tradition. Col. Astor had possession of most of the latter class of property for only five years, or between his mother's death and his own. That he enjoyed these hundreds of paintings, porcelains, and art objects with a sense of tangible personal ownership is a debatable question. The internal evidence of the appraiser's report and Col. Astor's career indicate that he did not.

The distinction is emphasized by the appraisal. The art objects purchased by Col. Astor are segregated from those which passed to him from his mother, thus adding to the impression of Col. Astor's simple tastes. His bedroom furnishings were not more costly than would be those of a man whose entire fortune was represented by the ornaments of the adjoining apartments. Compared with the valuation of $3,609 placed on the contents of "Col. Astor's room," for example, are these of other rooms in the residence:

Entrance hall..................... $16,067

Library................................. 68,589

Drawing room..................... 68,275

Picture gallery..................... 22,357

Morning room................... 126,005

Dining room........................ 75,400

North reception room........ 16,780

South reception room........ 15,470

The contrast is also marked in the appraisal of the family jewels and of Col. Astor's personal ornaments. The jewels in the estate vaults were valued at $161,920. Of this sum $150,000 was represented by a diamond sunburst, a necklace, and earrings which are subjects of family dispute. Aside from Col. Astor's Santiago and society medals, the remaining articles, appraised at $11,920, seem to be family not personal acquisitions. Among the watches, rings, lockets, and pins are a number bearing the initials of Col. Astor's father, William Astor.

His Jewelry

Col. Astor's personal jewelry, on the other hand, was appraised at only $6,612. The inventory chiefly creates an impression of a man who went in very strongly for cuff links and waistcoat buttons. There are eight sets of sleeve buttons, ranging from simple gold links to squares of rubles and disks of platinum and diamonds. The cuff links represent an investment of $800. Six pairs of waistcoat buttons, some of them studded with sapphires, diamonds, rubies, and pearls, represent an investment of $6,500. Four watches and as many more jeweled stickpins, in addition to pencils, chains, and desk and toilet accessories, could be matched on the dressing tables of many American men with far less pretentions to wealth than Col. Astor. The same might be said of his wearing apparel at the Fifth Avenue house. Three fur coats, valued at $1,170, bulk large, but $800 worth of other wearing apparel is matched by uniforms appraised at a similar amount.

Though the art collection of Col. Astor represents a fortune of no mean proportions, the appraiser's report shows that Col. Astor bought very few pictures or bronzes. The paintings of Millet, Corot, Schreyer, Meissonier and Van Marcke, the tapestries and similar treasures described in the newspapers a few days ago were not purchased by Col. Astor, but came to him from his father. When William Astor died in 1892, they were valued at $398,319. Now the entire collection is said to be worth $464,819. Of this sum, $66,500 represents Col. Astor's purchases; the paintings being appraised at $9,000 and the bronzes at $57,500. Even these were not numerous. The paintings consist of a portrait of Col. Astor, by Leon Bonnat, a decorative panel called "The Guitar Player," and F. S. Church's "Dancing Bears."

The most important of the bronzes is Houdon's "Head of Voltaire," valued at $15,000. The others comprise a "Flying Mercury" by Rustici, figures of Neptune, Apollo and Venus and Louis XIV. mounted on a charger and "Satyr and Bacchante," by Clodion.

Let us penetrate these externals and seek John Jacob Astor alone in his sanctum. There hints may be obtained of what he really wished to be - and might have been.

To do this, one must leave behind the showrooms of the Fifth Avenue residence and lay aside for the moment the portrait of Col. Astor in its conventional pose as he became more or less, familiar to the reading public.

Seeking this more intimate man, attention must be directed to three rooms in the Fifth Avenue residence which have been ignored in the newspaper reports of the appraisal and the existence of which was possibly realized only vaguely by those who dined at Col. Astor's table and danced in his ballroom.

Two of these rooms are in the basement, the third on the third floor. One basement room is set down in the appraiser's report as the laboratory. Its contents are valued at $1,000, none of the details being given. Adjoining it is a bedroom with an enameled bed and oak furniture worth not more than $100.

The room on the third floor was Col. Astor's library; those who entered it would not be likely to find much to excite their wonder. A flat top oak desk, armchairs in leather and velours, a globe, an old self-playing piano, an inexpensive carpet, a carved Italian armchair and their accessories might be purchased for $2,000 or so. On the bookshelves were no first or early editions or bindings demanding special attention.

In this room and the laboratory in the basement Col. Astor spent much of his time. His friends regarded him as a man with a serious turn of mind in matters relating to science and invention.

As an Inventor

He invented a pneumatic machine to remove material from worn-out roads and was awarded a prize for it at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. Another of his contrivances was a "vibratory disintegrator" to manufacture gas fuel from peat. A bicycle brake based on the principle of reduced friction, and a variation of a turbine engine represented other experiments. In 1910 he came forward with a device for a steamship chair with vacuum cups to hold it securely to the floor of a deck or cabin, thus supplanting fixed chairs on steamships.

For more than twelve months a mysterious craft lay in the Harlem River several years ago. It seemed to embody some idea to combine an airship with a practical water craft. Nothing seemed to come of the enterprise, and finally the boat disappeared. Col. Astor was mentioned at the time as the man who was behind the enterprise. On another occasion his application for a patent for an elaborate rainmaking machine was not granted owing to an objection that it anticipated the use of natural forces that could not be called exclusive.

Hidden away, too, in the list of stocks and bonds of the appraiser's report is another indication of Mr. Astor's enthusiasm in matters scientific. The item enumerates 500 shares of stock in the Nikola Tesla Company, of "nominal" value. Commenting on this investment, Nicholas Biddle, who was closely associated with Col. Astor in his business affairs, had this to say:

"Impossible to Sell"

This stock was not carried on Col. Astor's books. It was purchased by Col. Astor under an agreement made with Mr. Tesla personally, of which his office had no information. The stock has never paid any dividends, and it is my understanding that the proceeds from the sales of the stock were used in certain experimental work which has not developed into a paying industry, and in my judgment it would be impossible to sell this stock."

In Col. Astor's library is also a reminder of his adventure in authorship, which led to his election as a member of the Authors' Club, but resulted otherwise in a newspaper sensation of the moment rather than a permanent addition to science or literature. In 1910 appeared his romance, "A Journey in Other Worlds." He coined the word "apergy" to describe a force counteracting gravitation, and described a fantastic journey to Jupiter and Saturn.

In the appraisal of Col. Astor's private library are 165 copies of his book. In the main library on the first floor are stored another 100 unsold volumes. They go into the appraiser's report at a valuation of $1.50 each.

Was Col. Astor a good business man? On the death of his father, William Astor, in 1890, the family fortune was generally estimated to be about $65,000,000, compared with the gross valuation of $87,218,794 at Col. Astor's death, twenty years later. Seeking a reply to the question, the published outlines of the appraiser's report are also found to be deceptive.

As a man of 29 years, Col. Astor assumed the responsibility of his property at the estate offices, in West Twenty-sixth Street, and managed it for nearly twenty years. Nor was he merely a figurehead, dependent on his co-trustees and expert advisers, according to the testimony of Mr. Biddle which accompanies the appraisal.

His Hotel Properties

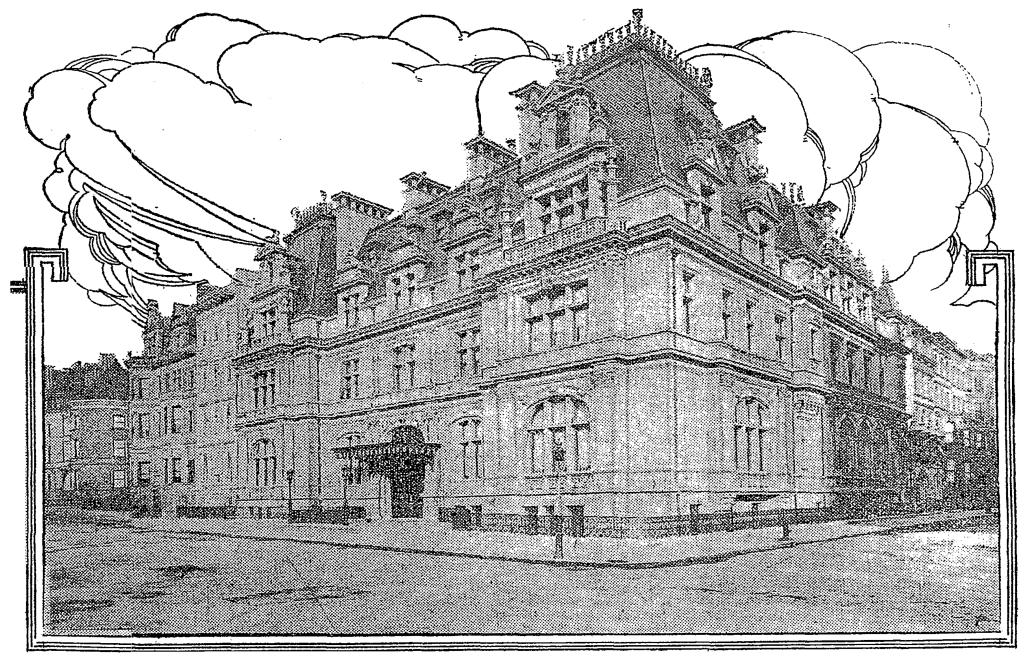

In his large building projects Col. Astor followed the example of his cousin, William Waldorf Astor, rather than assumed an aggressive initiative. Thus his portion of the great hostelry at Thirty-fourth Street and Fifth Avenue, the Astoria, was put up after the Waldorf, at Thirty-third Street. In Times Square his cousin built the Hotel Astor before Col. Astor erected the Knickerbocker Hotel. In upper Fifth Avenue the New Netherland of William Waldorf Astor long antedated his cousin's Hotel St. Regis.

Among Col. Astor's stocks and bonds the appraisal shows many of standard values. With others there is an impression that Col. Astor was "stung." In the eighty-nine separate items appear thirty-nine, or more than one-fourth, appraised as having a nominal value or doubtful value.

A careful analysis, however, shows that a number of these securities represent contributions which men in Col. Astor's position might be expected to make to social or public enterprises, that others were losing ventures of his father, and that a third class represent Col. Astor's personal losses.

Among the securities, for example, are those of the New Theatre, Col. Astor's holdings comprising a box-holder's certificate, 100 shares of stock of a par value of $10,000, and $25,000 in bonds. Their value is appraised as "nominal."

"That value was fixed," testified Mr. Biddle, "by Mr. Henry Rogers Winthrop, who was an officer of the New Theatre, and he advised me that the New Theatre, as what I might call a going concern, is out of business. The box owner's certificates would be valuable only as works of art, and, of course, they have no value, as the New Theatre is not conducted by the former management, and I understand that the property is leased at an amount sufficient only to cover the interest on the first mortgage bonds and cannot even pay the interest on the income bonds."

The other securities of Col. Astor's estate traceable to his social and public activities are the following:

One share of the Alumni House Association, $100. This was a benevolent association in connection with St. Paul's School, at Concord, N. H., which Col. Astor attended. His affection for the school is shown by his will, a $30,000 legacy being his sole bequest to an institution.

A 1-450th share of the net assets on final liquidation of the Country Club of Westchester County, valued at $150.

Twenty-five shares of the Dutchess County Agricultural Society, of a par value of $250.

Five shares of the Livestock Society of America, of a par value of $250.

Forty-five shares of preferred and twenty-two shares of common stock in the Long Island Motor Parkway, valued at $6,700.

Five thousand dollars of gold income bonds in the Colony Club.

In addition to these are stocks and bonds of a similar class of appraised values as follows:

The 300 shares of the Metropolitan Opera and Real Estate Company of a par value of $15,000 are appraised at $100,000.

Four shares in the Newport Casino of a par value $2,000 are said to be worth $1,300.

The 108 shares of the Newport Country Club stock of a par value $10,800 are appraised at $2,700.

Two shares in the Newport Reading Room of a par value of $200 show a handsome premium in an appraised value of $700. Par value was allowed on four shares, of a par value of $2,000, in the Spouting Rock Beach Association, representing an interest in the bathing beach at Newport.

Five thousand dollars in first mortgage bonds of the Automobile Club of America are appraised at $4,000, and $11,000 second mortgage bonds of the same club are appraised at $7,700.

The $5,000 bonds of the Sleepy Hollow Club are appraised at par.

Col. Astor was apparently solely responsible for the following:

Certificates for 200 shares in the Amphere Electro Company of a par value of $20,000. "From information received a number of years ago," testified Mr. Biddle, "we have carried it on our books as worthless, and it appears in the records of obsolete securities that the charter of this company was forfeited for unpaid taxes in 1907."

Two hundred shares in the Atmospheric Products Company of a par value of $20,000. "That company has also ceased to do business, and this stock has been carried on our books for a number of years as worthless."

A certificate for 15 shares of Chestnut Ridge Railroad Company stock, of a par value of $1,500. "A mortgage was foreclosed and the stock rendered worthless about 1901."

A certificate for 20 shares of the College World Company, of a par value of $100. "The charter of this company was forfeited for unpaid taxes, I am informed, about 1906."

Two hundred and fifty shares of the Commercial Bank of Honduras, of a par value of $2,500. "The charter of that bank has been revoked by the Government of Honduras. They have no assets. It also has been carried on the books of Col. Astor as valueless for some years."

Two thousand shares of the Depew Improvement Company, of a par value of $200,000. "This company went into the hands of a receiver in 1904 and is now out of existence, as it was taken over by the Lands Company of Depew." Further down in the inventory 1,981 shares in the Lands Company of Depew, of a par value of $198,100, which is appraised at $99,050. This was received in exchange for the bonds.

A certificate for 1,950 shares of the Honduras Railroad Company, of a par value of $193,000. "That company is out of existence. I understand their charter has been forfeited by the Government of Honduras."

"That was the company that Col. Astor went into some fifteen years ago?" Mr. Biddle was asked.

Various Securities

"About that," he replied. "I might add that in the New Jersey transfer tax upon this estate this stock was appraised as of nominal value and the New Jersey authorities acquiesced in such an appraisal."

A certificate for 25 shares of the Honduras Syndicate, 70 per cent. paid, of a par value of $1,750. "The same condition exists as in regard to the Honduras Railroad," commented Mr. Biddle. "The charter of this company was forfeited for unpaid taxes about 1908."

A certificate for 500 shares of International Power Storage Company of a par value of $25,000. "The charter of this company was forfeited for unpaid taxes about 1902."

One hundred shares of Mutual Automatic Telephone Company stock, of a par value of $10,000. "This company is no longer doing business, as I am informed."

Seventy-five shares New York and Pennsylvania Brick, Tile and Terra Cotta Company, of a par value of $7,500. "I can find no record of that company," explained Mr. Biddle. "I have sent to an address in New York at which it formerly did business and it is not there any longer and I could find no record of where It has gone to."

Certificates for 600 shares in the Port Chester Chemical Company. "I have been unable to obtain any information with regard to this company."

A certificate for 104 shares of Rider and Driver Publishing Company. Mr. Biddle said he had been unable to obtain definite information from the company regarding the value of the stock.

A certificate for 100 shares of the Union Car Company, of a par value of $10,000. "This company is out of existence," said Mr. Biddle. "I don't remember whether it was carried on Col. Astor's books or not."