Nikola Tesla Articles

This Giant could Wreck New York

The 7,000,000 Man Power Electric Force Running Through the Wire Veins or the Metropolis and How It Is Guarded Against Escaping to Spread Devastation.

Whoever has been upon a street car when a fuse burned out, have no doubt wondered what would happen if all the electricity in this most electric city of the world got loose.

There is an immediate exodus from the car. Often all of the car that is combustible is consumed by flame before the nearest fire engine can be brought to the spot. Between the first startling sharp report and the ignition of woodwork and the melting of insulation the period is short. But only one car is involved — or a train of cars, as one day last year in the Subway. In the event of a simultaneous breaking of bounds all over town by this marvellous agent which we hold to slavery by shackles confessedly weak, what would it do to Manhattan?

Manhattan and the Bronx has seized and harnessed and put to labor electricity to the total of 1,000,000 horse-power. The strength of a million horses! It does the equivalent of the work of 8,000,000 men — indeed, two and, one-half times that number, for it sustains its power not for eight or nine hours but for twenty-four — adding to New York's industrial output nearly six times that of all the males in this tremendous city.

Here are the capacities of the power stations in horse-power:

| Rapid Transit Subway | 130,000 |

| Metropolitan Railway | 98,000 |

| Manhattan Railway | 100,000 |

| New York City Railway | 96,000 |

| New York Central Railway (by July) | 100,000 |

| Edison Company | 216,000 |

| United Company | 90,000 |

| Pennsylvania Railroad | 95,000 |

| Private plants | 135,000 |

| Municipal lights | 20,000 |

| Total | 1,070.000 |

In addition, there are the Edison light storage batteries In twenty different buildings on Manhattan, holding 75,000 horse-power for emergency. This, more than a million electric horse-power — practically all in Manhattan — is three times what there was in the entire United States seven years ago. In the Greater City two-million-man power may be added to the figures.

When Electricity Does Escape.

Electricians assert that in electrical science there is no such term as "breaking loose." Yet electricity does escape from third rails and light wires and wanders about town, eating copper roofs, corroding bridges and the steel frames of buildings.

At a recent hearing on the cost of gas, sections of iron pipe were shown in which vagrant electricity had bored immense holes. At a moment of puncture, if air were present, it is conceded that a spark would result and an explosion follow. Many a mysterious explosion has been caused by the wearing off of the insulation of wires and the instant ignition of leaked gas.

"The leakage of electricity is undeniably considerable," declared the editor of the Electrical Age the other day, "and the problem how to stop It is now the object of anxious research and experiment. In some cities electric railways are seriously troubled by the quantity that gets free. Conduits are made of fire-clay, and all known precautions are taken, but it is true that electrolysis is acting into the steel frames of modern buildings and iron structures generally electrolysis being the decomposition caused by errant electricity."

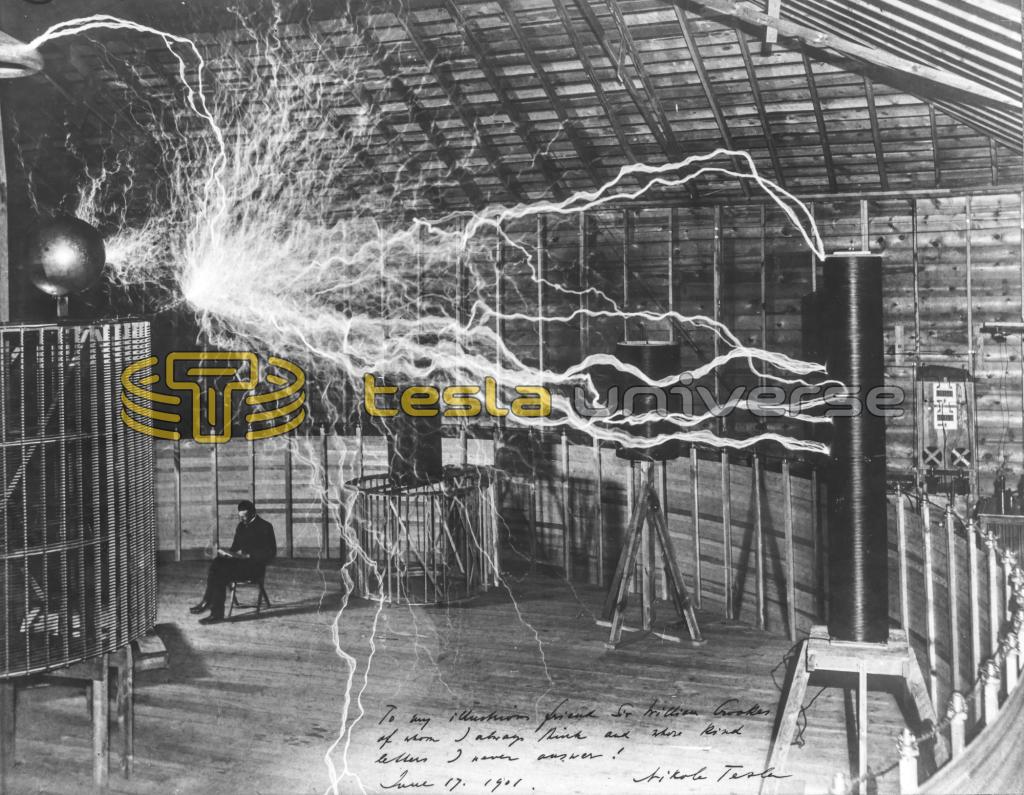

These photographs of Nikola Tesla's magnifying transmitter were made under Mr. Tesla's supervision at his Long Island laboratory. The upper picture shows the results of a double exposure, one made to record the leaping electric flames forty feet long, the second to impress on the plate the seated figure of Mr. Tesla himself. The potentiality of this remarkable exhibition of electrical force has been estimated at 25,000,000 horse-power — five times the power of Niagara.

A definite impression exists that in relation to this subtle power, the nature of which we do not know, we may be dwelling in a false security.

Most of us know from photographs, at least, what electricity looks like when it leaps from one grounded pole to another. It streams across the intervening space in weird dazzling undulations. White tatters of ribbons — broken gleams, radiations, streaks — wave more erratically than strands snapping in a gale.

On this page you may see such a photograph, with a man calmly reading a newspaper a few feet beyond. Of course the man was not really there. Short time he would have lasted! By a well-known trick of photograph-making the picture of the man calmly reading was superimposed upon a picture of electricity darting from pole to pole.

Supposing all the electricity produced continuously in Manhattan were thus to disport itself? What could it do? Suppose it possible that this giant which we have set to drive wheels, make beat and supply light — which in this city we have compelled to operate the biggest artificial light system and the busiest transportation lines the world ever saw, at the same time subjecting its power to innumerable uses, even to curling a lady's hair, suppose all should escape, with its power of a million horses, what could it not do to Manhattan?

Dangers of a Short Circuit.

"Well, now," objects the practical electrician, cables would be burned up by that escape — then the engines which drive the dynamos would stop. Engines stop on a short circuit. Remember that there are two electricities — the negative and the positive — which tend to unite, and in uniting produce the electric current. One punctured insulation makes no trouble. There's nothing doing unless there is a puncture on the other cable also. When one escapes it dashes for the other by the shortest route. Why should the engines stop? Because 10,000 horse-power becomes by such a crossing of cables equal to 100,000 horse-power, and the engine having only 10.000 capacity would be overwhelmed."

Sixty thousand volts is the present safety limit for power transmission. Anything more bursts through all insulators yet devised. At Niagara a plant with 10,000 horse-power, transmits its current under a pressure of 20,000 volts. On the Manhattan Elevated and Subway roads the pressure is 12,000 volts; on the lighting wires 240 volts.

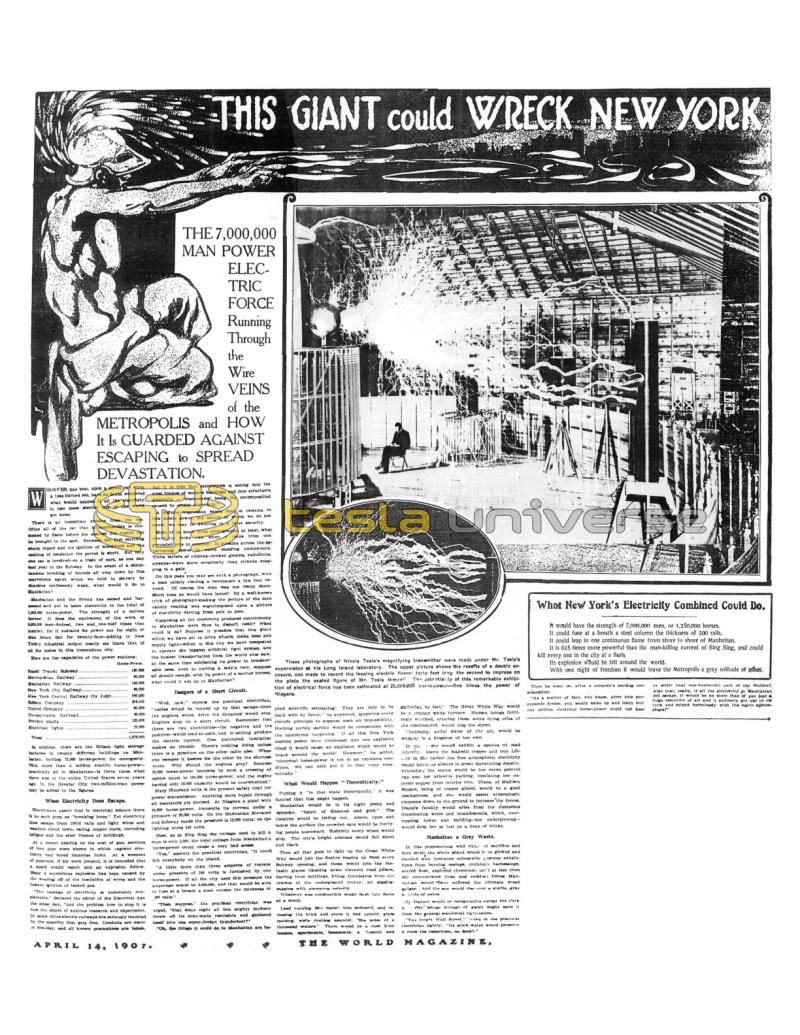

What New York's Electricity Combined Could Do.

- It would have the strength of 7,000,000 men, or 1,250,000 horses.

- It could fuse at a breath a steel column the thickness of 200 rails.

- It could leap in one continuous flame from shore to shore of Manhattan.

- It is 625 times more powerful than the man-killing current of Sing Sing, and could kill every one in the city at a flash.

- Its explosion would be felt around the world.

- With one night of freedom it would leave the Metropolis a gray solitude of ashes.

Now, as at Sing Sing the voltage used to kill a man is only 2,000, the total voltage from Manhattan's horse-power could cause a very bad scene.

"Yes," assents the practical electrician, "It could kill everybody on the island.

"A little more than three amperes of current under pressure of 240 volts is furnished by one horse-power. If all the city used this pressure the amperage would be 3,000,000; and that would be able to fuse at a breath a steel column the thickness of 200 rails."

"Then suppose," the practical electrician was urged, "that some night all this mighty mystery threw off its man-made restraints and gathered itself into one super-Jovian thunderbolt?"

"Oh, the things it could do to Manhattan are beyond scientific estimating! They are only to he dealt with by fancy," he answered, ignoring every electric principle to suppose such an impossibility. Nothing merely earthly would be comparable with the monstrous happening. If all this New York electric power were condensed into one explosive cloud it would cause an explosion which would be heard around the world! However," he added, "electrical horse-power is not in an explosive condition. We can only put it in that state theoretically."

What Would Happen "Theoretically."

Putting it "in that state theoretically," it was fancied that this might happen.

Manhattan would be in its night pomp and splendor, "fabric of diamond and gold." The theaters would be letting out. Above, upon and below the surface the crowded cars would be hurrying people homeward. Suddenly every wheel would stop. The city's bright avenues would fall silent and black.

Then all that goes to light up the Great White Way would join the flashes leaping up from every Subway opening, and these would join the fantastic glares climbing down elevated road pillars, darting from buildings, lifting themselves from the crevice of the underground trolley; all zigging-zagging with enormous velocity.

Whatever was combustible would flash into flame at a touch.

Lead running like water; iron softened, and releasing the brick and stone it had upheld; glass melting, walls rushing asunder, "the noise of a thousand waters." There would be a rush from houses, apartments, tenements; a "tumult and gathering of feet." The Great White Way would be a roaring white furnace. Human beings thrill- ingly shocked, uttering those weird dying cries of the electrocuted, would clog the street.

Electricity, awful sister of the air, would be walking in a kingdom of her own.

In time, she would exhibit a species of mad hilarity. Above the majestic copper and iron Liberty in the harbor the free atmospheric electricity would hover as always in great threatening density. Protecting the statue would be her seven pointed cap and her asbestos packing, insulating her exterior copper from interior iron. Diana, of Madison Square, being of copper gilded, would be a good conductress, and she would assist atmospheric electrons down to the ground to increase the forces. Diana's fatality would arise from the numerous illuminating wires and incandescents, which, overrunning tower and building — her underpinning — would drop her at last on a heap of bricks.

Manhattan a Gray Waste.

In this preposterous wild ritual of sacrifice and fiery strife the whole island would have glowed and smelled with luminous unbearable gaseous exhalations from burning casings, clothing, harnessings, seared flesh, exploded chemicals; until at last from the concentrated loose and rookies; forces Manhattan would have suffered the ultimate dread eclipse. And the sun would rise over a sterile, gray solitude of ashes.

My feature would be recognizable except the Park Reservoir, whose storage of water might save it from the general sepulchral obliteration.

"You forget Wall Street," broke in the practical electrician lightly. "Its stock-water would preserve it from the cataclysm, no doubt,"

Then he went on, after a moment's smiling consideration:

"As a matter of fact, you know, after this paroxysmic dream, you would wake up and learn that our million electrical horse-power could not heat to white heat one-hundredth part of the Waldorf. Also that, really, if all the electricity in Manhattan did escape, it would be no more than if you had a huge reservoir of air and it suddenly got out of its tank and mixed harmlessly with the outer atmosphere!"