Nikola Tesla Articles

It Happened in Colorado - A World's First in Engineering History

In 1891, Colorado scored a "World's First" in engineering history. It was in late June of that year when the power plant at Ames, Colorado, became the first power station in the world to transmit alternating current at high voltage for power purposes. The distance was about three miles.

This unique experiment had its birth in necessity. The Gold King Mining Company which operated near the Alta Lakes, had been going in the red for some time. Timber for fuel near the mine had been exhausted. Coal delivered by burro-pack cost a prohibitive forty to fifty dollars per ton. L. L. Nunn, a peppery little lawyer from Telluride, was secured to solve the problems of the company.

L. L. Nunn was a giant of a little man, frail in health but endowed with a dynamic drive which Nature so often bestows on undersized people. He was the same height as Napoleon, and almost as ambitious. He was resourceful. He had tried his hand at the restaurant business in Leadville, picked up his saw and hammer when the building boom got out of hand, collected rent for his tin bath tub from Saturday-night-playboys in Telluride, and hung up his shingle to offer his services as a lawyer to the legally embroiled mining area.

When he took over the management of the Gold King property, he realized that some system of electrical transmission was necessary. For some time he had eyed the possibility of utilizing the power of the south fork of the San Miguel river. This river descended from Ophir, and fell 500 feet in less than a mile. The stream was fed by springs that made certain ample water supply at all seasons and could furnish water power enough for every mine in the vicinity if a feasible means of transmission could be worked out. Nunn was no engineer, but he knew where to put his finger on a good one. He sent for his brother, Paul N. Nunn.

Nunn had long been interested in George Westinghouse. The "war of the currents" raging between the advocates of alternating current, promoted by Westinghouse, and the believers in Edison's direct current was causing a furor in industry. When the Gold King Mining Company decided to sign a contract with the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, there was very little concern in eastern engineering circles. No optimism was held out for the Colorado experiment. It was of little importance to the east outside of a few reckless investors.

Colorado turned out to be the proper stage for this venture. Western enthusiasm drew young men on this project to match the mountains. It was "Otto Mears country," where railroads careened around dizzy cliffs, and crossed cantankerous creeks, where men rode buckets to the high mines and risked life every day. It was a young country, raw, brash and unbeatable.

To man this new power experiment, young men came from Cornell University and from mining camps, anxious to learn. Nunn housed the boys in Telluride, in a school that combined study with actual, on the job, experience. The boys climbed the poles, strung the wires, invented their own lightning arresters and solved their own problems. They called themselves Pin Heads. They learned the hard way. Their school was called the Telluride Institute.

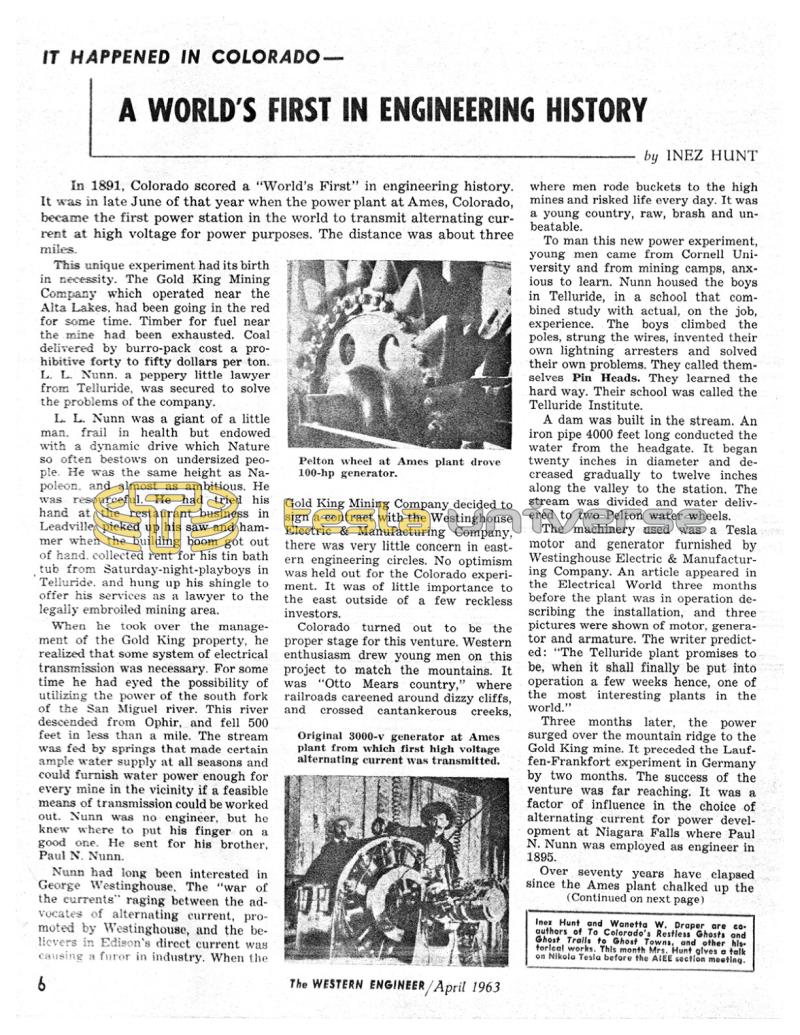

A dam was built in the stream. An iron pipe 4000 feet long conducted the water from the headgate. It began twenty inches in diameter and decreased gradually to twelve inches along the valley to the station. The stream was divided and water delivered to two Pelton water wheels.

The machinery used was a Tesla motor and generator furnished by Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company. An article appeared in the Electrical World three months before the plant was in operation describing the installation, and three pictures were shown of motor, generator and armature. The writer predicted: "The Telluride plant promises to be, when it shall finally be put into operation a few weeks hence, one of the most interesting plants in the world."

Three months later, the power surged over the mountain ridge to the Gold King mine. It preceded the Lauffen-Frankfort experiment in Germany by two months. The success of the venture was far reaching. It was a factor of influence in the choice of alternating current for power development at Niagara Falls where Paul N. Nunn was employed as engineer in 1895.

Over seventy years have elapsed since the Ames plant chalked up the victory. The installation there is now a part of Western Colorado Power Company, a subsidiary of the Utah Power and Light Company. The memory of L. L. Nunn and the Telluride Institute is preserved at Cornell University where the Telluride Association provides scholarship opportunity through endowment by Nunn.

But the strange electrical genius, Nikola Tesla, whose patents made possible this experiment is known and remembered by only a few.

Inez Hunt and Wanetta W. Draper are co-authors of To Colorado's Restless Ghosts and Ghost Trails to Ghost Towns, and other historical works. This month Mrs. Hunt gives a talk on Nikola Tesla before the AIEE section meeting.