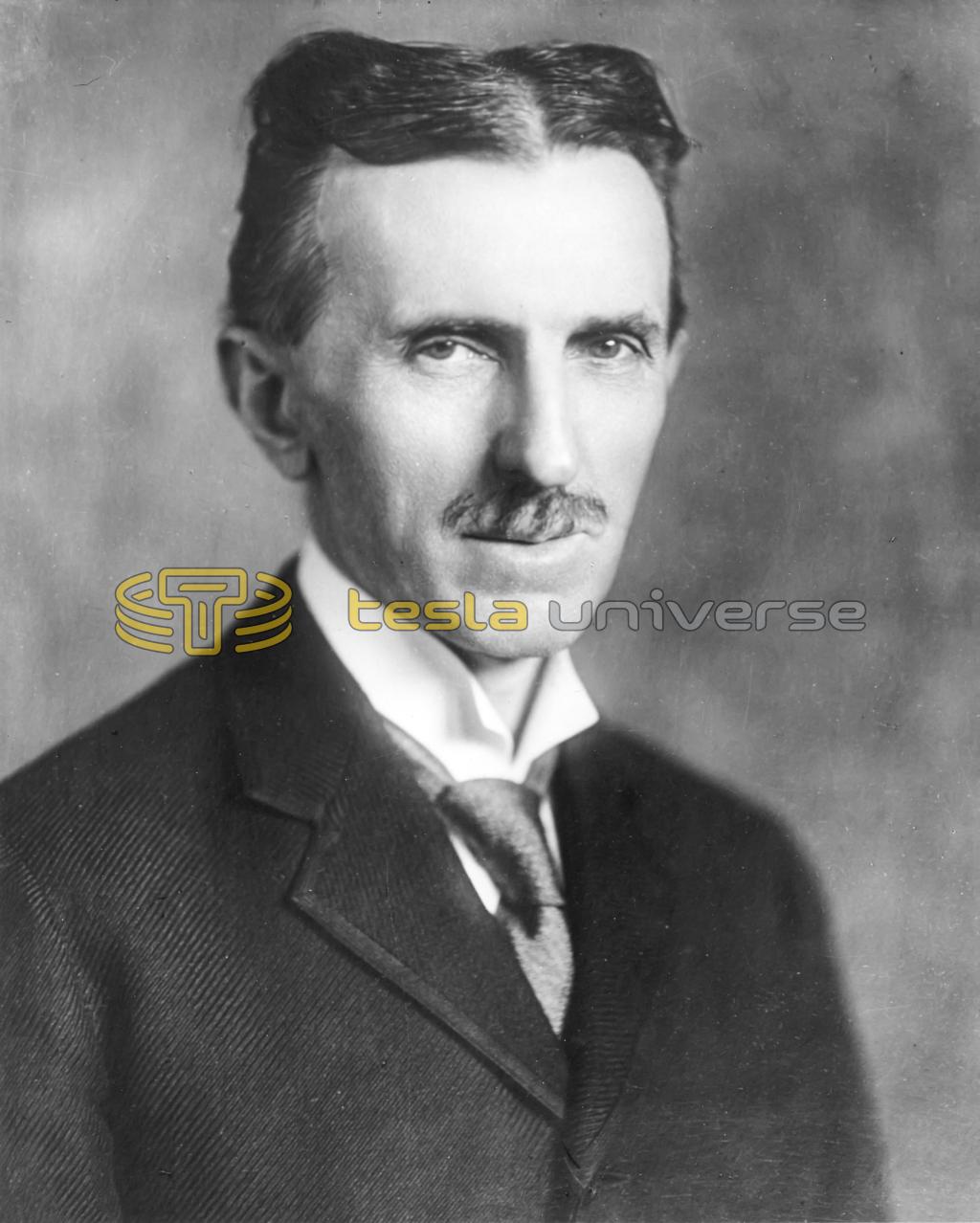

Nikola Tesla Articles

Making Your Imagination Work for You

An interview with Nikola Tesla, great inventor, who tells the romantic story of his life. He also describes a method of work he has evolved, which will be of use to any imaginative man, whether he is an inventor, business man, or artist.

There were two inventions to my credit before I was six years old. The first was a hook for catching bullfrogs. A boy in our little village of Smiljan, Jugo-Slavia, had received a present of a hook and fishing tackle. This made a great stir among my playmates, and the next morning they all started out to catch frogs; but I was left alone because I'd had a quarrel with the boy who owned the tackle.

I never had seen a hook, and I imagined it to be a wonderful something with mysterious qualities; but, prompted by necessity, I got hold of a piece of soft iron wire, bent it, and sharpened it by means of two stones. Then I attached it to a strong string, cut a rod, gathered bait, and went to the brook, where the frogs were innumerable.

In vain I tried to capture the frogs in the water; and I was humiliated to think what a big catch my playmates would bring home with their fine tackle. But at last I dangled my empty hook in front of a frog sitting on a stump, and I can see now in my mind's eye what happened as vividly as though it were yesterday.

First, the frog collapsed, then his eyes bulged, and he swelled to twice his normal size, made a vicious snap at the hook — and I pulled him in. This method proved so infallible that I went home with a fine catch, whereas my playmates caught none. To this day I consider my frog-hook invention quite remarkable and very ambitious. It involved the invention both of an apparatus and a method. I may have been anticipated in the former, but I like to think that the latter was original.

My second invention was prompted by the very same desire that guides me in all I do to-day, the desire to harness the forces of nature to the service of man. This I did, at that time, through the medium of May bugs, or June bugs as we call them in America. These bugs were such a pest in our neighborhood that sometimes the sheer weight of their bodies brought down branches of trees.

Four of the bugs J attached to a crosspiece of wood, which was arranged so as to rotate on a thin spindle. The motion of the spindle was transmitted to a large disk, and in this way I derived my power; for, once started going, the May bugs never knew when to stop; the hotter it was, the harder they worked. This invention gave me complete satisfaction until one day I saw the son of a retired officer of the Austrian army eating May bugs, and seeming to enjoy them. I never played with the bugs after that, and to this day I shrink from touching any kind of insect.

The memories of my youth and even of earliest childhood are very vivid, and it seems to me that my character began to develop a little sooner than is the case with most people. As a very small boy I was weak and vacillating, and made many childish resolves, only to break them. But when I was eight years old I read "The Son of Aba," a Serbian translation of a Hungarian writer, Josika, whose lessons are similar to those of Lew Wallace in Ben Hur. This book awakened my will power. I began to practice self-control, subdued many of my wishes, and resolved to keep every promise I ever made, whether to myself or to anyone else. The members of my family were not long in learning that if I promised a thing I would do it.

Long before I was twenty, I was smoking excessively — fifteen or twenty big black cigars every day. My health was threatened, and my family often tried to get me to promise to stop, but I would not.

One day I was standing in front of our house, when they told me the doctor had just said that my youngest sister, who had been very ill for some time, was dying. I went up to her room, carrying my lighted cigar, and before kneeling at her bedside I placed the cigar on a little table beside the bed.

"Niko," she said, so faintly that I could hardly hear her, "you are killing yourself with smoking. Promise me you will give it up."

"Yes," I said; "if you will get well, I promise to give up smoking."

"All right, Niko," she said feebly. "I will try."

She did get well, and I have never smoked since. It was very hard to give it up, but I was determined to keep my promise. Not only did I stop, but I finally destroyed every inclination for what had been such a great satisfaction. In this way I have freed myself of other habits and passions, and so have preserved my health and my zest for life. The satisfaction derived from demonstrating my own strength of will has always meant more to me in the end than the pleasurable habits I gave up. I believe that a man can and should stop any habit he recognizes to be "foolish."

When I was about twenty, I contracted a mania for gambling. We played for very high stakes; and more than one of my companions gambled away the full value of his home. My luck was generally bad, but on one occasion I won everything in sight. Still I was not satisfied, but must go on with the play. I lent my companions money so that we might continue, and before we left the table I had lost all that I had won and was in debt.

My parents were greatly worried by my gambling habits. My father especially was stern and often expressed his contempt at my wanton waste of time and money. However, I never would promise him to give up gambling, but instead defended myself with a bad philosophy that is very common. I told him that, of course, I could stop whenever I pleased, but that it was not worth while to give up gambling because the pleasure was more to me than the joys of Paradise.

My mother understood human nature better and never chided. She knew that a man cannot be saved from his own foolishness or vice by someone else's efforts or protests, but only by the use of his own will. One afternoon, when I had lost all my money, but still was craving to play, she came to me with a roll of bills in her hand — a large sum of money for those times and conditions — and said, "Here, Niko. Take these. They're all I have. But the sooner you lose everything we own, the better it will be. Then I know you will get over this."

She kissed me.

So blinded was I by my passion that I took the money, gambled the whole night, and lost everything, as usual. It was morning when I emerged from the den, and I went on a long walk through sunlit woods pondering my utter folly. The sight of nature had brought me to my senses, and my mother's act and faith came vividly to mind. Before I left the woods, I had conquered this passion. I went home to my mother and told her I never would gamble again. And there never has been the slightest danger of my breaking the promise.

My father was the son of an officer who served in the army of the Great Napoleon. He himself had received military training, and oddly enough, had subsequently embraced the clerical profession. A philosopher, poet, and writer, he achieved eminence as a preacher because of his learning and eloquence. But it is to my mother, I believe, that I trace my inventiveness. Her father and grandfather originated numerous implements for household and agricultural uses. My mother herself invented and constructed all kinds of tools and devices, and wove the finest designs from thread, spun by herself. I have always thought that my mother would have achieved great things if we had not lived so far from the opportunities of modern life.

Both my father and mother were very eager that I should become a preacher; but I had no leaning in that direction. From the age of ten I had been inventing all sorts of things in my mind: flying machines, a submarine tube for carrying letters and packages under the Atlantic, and means of getting power from the rotation of the planets; all fanciful, but even after I had gone to study at the gymnasium at Carlstadt, Croatia, where I became intensely interested in physics and electricity, my parents still wanted me to become a preacher.

Perhaps, if I had not become very ill, I should have given my promise. But because of overstudy, I had my first serious breakdown in health. Physicians absolutely gave me up. It was an American genius who saved my life.

During my illness I read books by the score from the public library, and one day I was handed a few volumes unlike anything I had ever read, and so interesting that I forgot my hopeless state. My recovery seemed miraculous.

The books I had been reading were the early works of Mark Twain — among them "Tom Sawyer," and "Huckleberry Finn." Twenty-five years later, when I met Mr. Clemens and we formed a lifelong friendship, I told him of this experience and of my belief that l owed my life to his books. I was deeply moved to see tears come to the eyes of this great man of laughter.

After graduating from the Higher Realschule at Carlstadt, I went home to my parents, and on the very day of my arrival was stricken with cholera, which was then epidemic in those parts. Again I was near death. My father tried to cheer me with hopeful words.

"Perhaps," I said, "I might get well, if you would let me become an engineer instead of a clergyman."

He promised solemnly that I should go to the best technical institution in the world. This, literally, put new life into me; and, owing partly to my improved state of mind and partly to a wonderful medicine, I recovered. My father kept his word by sending me to the Polytechnic School in Gratz, Styria, one of the oldest institutions of Europe.

All during my first year there I started work at three A. M. and continued until eleven P. M., neither Sundays nor holidays being excepted. Such leisure as I allowed myself I spent in the library. It was during my second year that something happened that has determined the whole course of my life. To make this clear, I must tell you about an early experience.

During my boyhood I had suffered from a peculiar affliction due to the appearance of images, which were often accompanied by strong flashes of light. When a word was spoken, the image of the object designated would present itself so vividly to my vision that I could not tell whether what I saw was real or not. If I had witnessed a funeral, or perhaps come close to some wounded animal while on a hunting trip, then inevitably in the stillness of night a vivid picture of the scene would thrust itself before my eyes and persist, despite all my efforts to banish it. Even though I reached out and passed my hand through it, the image would remain fixed in space.

In trying to free myself from these tormenting appearances, I tried to concentrate my mind on some peaceful, quieting scene I had witnessed. This would give me momentary relief; but when I had done it two or three times the remedy would begin to lose its force. Then I began to take mental excursions beyond the small world of my actual knowledge. Day and night, in imagination, I went on journeys — saw new places, cities, countries, and all the time I tried very hard to make these imaginary things very sharp and clear in my mind. I imagined myself living in countries I never had seen, and I made imaginary friends, who were very dear to me and really seemed alive.

This I did constantly until I was about seventeen, when my thoughts turned seriously to invention. Then, to my delight, I found that I could visualize with the greatest facility. I needed no models, drawings, or experiments. I could picture them all in my mind.

During my second year at the Polytechnic Institute, we received a Gramme dynamo from Paris. It had a horseshoe form of field magnet and a wire-wound armature with a commutator — a type of machine that has since become antiquated. While the professor was demonstrating with this machine, the brushes sparked badly, and I suggested that it might be possible to operate a motor without such appliances. The professor declared that I could never create such a motor, because the idea was equivalent to a perpetual motion scheme.

This statement from such a high authority caused me to waver in my belief for some time. Then I took courage and began to think intently of the problem, trying to visualize the kind of machine I wanted to build, constructing all its parts in my imagination. These images were as clear and distinct as those I had conjured up to drive away the tormenting visions of my younger days. I conceived many schemes, changing them daily, but I did not at that time succeed in evolving a workable plan.

Four years later, in 1881, I was in Budapest, Hungary, studying the American telephone system, which was just being installed. But, during this interval, never for a day had I given up my attempt to visualize an electric motor without a commutator. In my anxiety to visualize one that would work, my health again broke down, just when I was feeling that the long sought solution was near; but after six months of careful nursing I recovered.

Then, one afternoon I was walking with a friend in the City Park and reciting poetry. At that time I knew entire books by heart, word for word. One of these was Goethe's "Faust;" and the setting sun reminded me of the passage:

The glow retreats, done is the day of toil;

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring;

Ah, that no wing can lift me from the soil,

Upon its track to follow, follow soaring!

Even while I was speaking these glorious words, the vision of my induction motor, complete, perfect, operable, came into my mind like a flash. I drew with a stick on the sand the vision I had seen. They were the same diagrams I was to show six years later before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. My friend understood the drawings perfectly; and to me the images were so real that suddenly I cried, "Look! Watch me reverse my motor!" And I did it, demonstrating with my stick.

This discovery is known as the "rotating magnetic field." It is the principle on which my induction motor operates. In this invention I produced a sort of magnetic cyclone which grips the rotable part and whirls it — exactly what my professor had said could never be done.

After inventing this motor, I gave myself up more intensely than ever to the enjoyment of picturing in my mind new kinds of machines. It was my great delight to imagine motors constantly running. In less than two months, I had created mentally nearly all the types of motors and modifications of the system which are now identified with my name.

It was in 1888, after I had come to America, that arrangements were made with the Westinghouse Company for the manufacture of this motor and for the introduction on a large scale of my system, which has since then been universally adopted. It gave the first great impetus to the harnessing of water power, to the development of trolley lines, subway systems and electric railways. It is embodied in the electric drive on battleships, and used as a means of transmitting power for innumerable purposes all over the world.

By that faculty of visualizing, which I learned in my boyish effort to rid myself of annoying images, I have evolved what is, I believe, a new method of materializing inventive ideas and conceptions. It is a method which may be of great usefulness to any imaginative man, whether he is an inventor, business man, or artist.

Some people, the moment they have a device to construct or any piece of work to perform, rush at it without adequate preparation, and immediately become engrossed in details, instead of the central idea. They may get results, but they sacrifice quality.

Here, in brief, is my own method: After experiencing a desire to invent a particular thing, I may go on for months or years with the idea in the back of my head. Whenever I feel like it, I roam around in my imagination and think about the problem without any deliberate concentration. This is a period of incubation.

Then follows a period of direct effort. I choose carefully the possible solutions of the problem. I am considering, and gradually center my mind on a narrowed field of investigation. Now, when I am deliberately thinking of the problem in its specific features, I may begin to feel that I am going to get the solution. And the wonderful thing is that if I do feel this way, then I know I have really solved the problem and shall get what I am after.

This feeling is as convincing to me as though I already had solved it. I have come to the conclusion that at this stage the actual solution is in my mind subconsciously, though it may be a long time before I am aware of it consciously.

Before I put a sketch on paper, the whole idea is worked out mentally. In my mind, I change the construction, make improvements, and even operate the device. Without ever having drawn a sketch, I can give the measurements of all parts to workmen, and when completed these parts will fit, just as certainly as though I had made accurate drawings. It is immaterial to me whether I run my machine in my mind or test it in my shop.

The inventions I have conceived in this way, have always worked. In thirty years there has not been a single exception. My first electric motor, the vacuum tube wireless light, my turbine engine, and many other devices have all been developed in exactly this way.

From Budapest I went to Paris, and there became associated with Mr. Charles Batchellor, an intimate friend and assistant of Mr. Edison. From Paris I made many trips throughout France and Germany, repairing the disorders of powerhouses; but I had no success in raising money for the development of my invention. I had already designed and constructed much improved electric machinery when Mr. Batchellor urged me to go to America and undertake the design of dynamos and motors for the Edison Company. So I decided to try my fortunes in this Land of Golden Promise.

On arriving here, I could see only the crudeness, in contrast with the gracefulness of Europe, and said, "America is twenty-five years behind Europe in civilization." But only five years later, I went abroad with new experience and became convinced that America is a century ahead of Europe in civilization. And that opinion I hold to this day.

One of the great events in my life was my first meeting with Edison. This wonderful man, who had received no scientific training, yet had accomplished so much, filled me with amazement. I felt that the time I had spent studying languages, literature and art was wasted; though later, of course, I learned this was not so.

It was only a few weeks after first meeting Mr. Edison, that I knew I had won his confidence. The fastest steamship afloat at that time, the Oregon, had disabled both her lighting engines, so that her sailing was delayed. The machines could not be removed from the ship because of the character of the superstructure, and the difficulty annoyed Mr. Edison considerably, because it seemed that the ship would be held in port some length of time.

That evening I took the necessary instruments and went aboard the ship. The dynamos were in bad condition, with short circuits and breaks; but with the aid of the crew I put them in shape. At five that morning, on my way home, I met Mr. Edison on Fifth Avenue, with Mr. Batchellor and their assistants, just going home from their own work. When Mr. Edison saw me, he laughed and said, "Here's our young man just over from Paris running around at all hours of the night." Then I told him I was coming from the "Oregon," and that I had repaired the machines. Without a word he turned away; but as they went on I heard him say, "Batchellor, this is a damn good man!"

Soon after I left Mr. Edison's employment a company was formed to develop my electric arc-light system. This system was adopted for street and factory lighting in 1886, but as yet I got no money — only a beautifully engraved stock certificate. Until April of the following year I had a hard financial struggle. Then a new company was formed, and provided me with a laboratory on Liberty Street, in New York City. Here I set to work to commercialize the inventions I had conceived in Europe.

After returning from Pittsburgh, where I spent a year assisting the Westinghouse Company in the design and manufacture of my motors, I resumed work in New York in a little laboratory on Grand Street, where I experienced one of the greatest moments of my life — the first demonstration of the wireless light.

I had been constructing with my assistants the first high-frequency alternators (dynamos), of the kind now used for generating power for wireless telegraphy. At three o'clock in the morning I came to the conclusion that I had overcome all the difficulties and that the machine would operate, and I sent my men to get something to eat. While they were gone I finished getting the machine ready, and arranged things so that there was nothing to be done, except to throw in a switch.

When my assistants returned I took a position in the middle of the laboratory, without any connection whatever between me and the machine to be tested. In each hand I held a long glass tube from which the air had been· exhausted. "If my theory is correct," I said, "when the switch is thrown in these tubes will become swords of fire." I ordered the room darkened and the switch thrown in — and instantly the glass tubes became brilliant swords of fire.

Under the influence of great exultation I waved them in circles round and round my head. My men were actually scared, so new and wonderful was the spectacle. They had not known of my wireless light theory, and for a moment they thought I was some kind of a magician or hypnotizer. But the wireless light was a reality, and with that experiment I achieved fame overnight.

Following this success, people of influence began to take an interest in me. I went into "society." And I gave entertainments in return; some at home, some in my laboratory — expensive ones, too. For the one and only time in my life, I tried to roar a little bit like a lion.

But after two years of this, I said to myself, "What have I done in the past twentx-four months?" And the answer was, "Little or nothing." I recognized that accomplishment requires isolation. I learned that the man who wants to achieve must give up many things — society, diversion, even rest — and must find his sole recreation and happiness in work. He will live largely with his conceptions and enterprises; they will be as real to him as worldly possessions and friends.

In recent years I have devoted myself to the problem of the wireless transmission of power. Power can be, and at no distant date will be, transmitted without wires, for all commercial uses, such as the lighting of homes and the driving of aeroplanes. I have discovered the essential principles, and it only remains to develop them commercially. When this is done, you will be able to go anywhere in the world — to the mountain top overlooking your farm, to the arctic, or to the desert — and set up a little equipment that will give you heat to cook with, and light to read by. This equipment will be carried in a satchel not as big as the ordinary suit case. In years to come wireless lights will be as common on the farms as ordinary electric lights are nowadays in our cities.

The matter of transmitting power by wireless is so well in hand that I can say I am ready now to transmit 100,000 horsepower by wireless without a loss of more than five percent in transmission. The plant required to transmit this amount will be much smaller than some of the wireless telegraph plants now existing, and will cost only $10,000,000, including water development and electrical apparatus. The effect will be the same whether the distance is one mile or ten thousand miles, and the power can be collected high in the air, underground, or on the ground.

A long time ago, I became possessed of a desire to produce an engine as simple as my induction motor; and my efforts have been rewarded. This engine has been perfected, is complete, and has been declared by the world's engineering experts to be a significant advance.

No mechanism could be simpler, and the beauty of it is that almost any amount of power can be obtained from it. In the induction motor I produced the rotation by setting up a magnetic well, while in the turbine I set up a whirl of steam or gas. The rotating part is nothing but a shaft with a few straight plates keyed to it. There are no buckets, blades nor veins. Machines of this kind can be produced that will develop ten horse-power for every pound of weight, while the lightest engines of the present day give only about one horse-power for each two pounds of weight, or one twentieth of the power developed by my turbine. I have no doubt that it is the engine of the future.