Nikola Tesla Articles

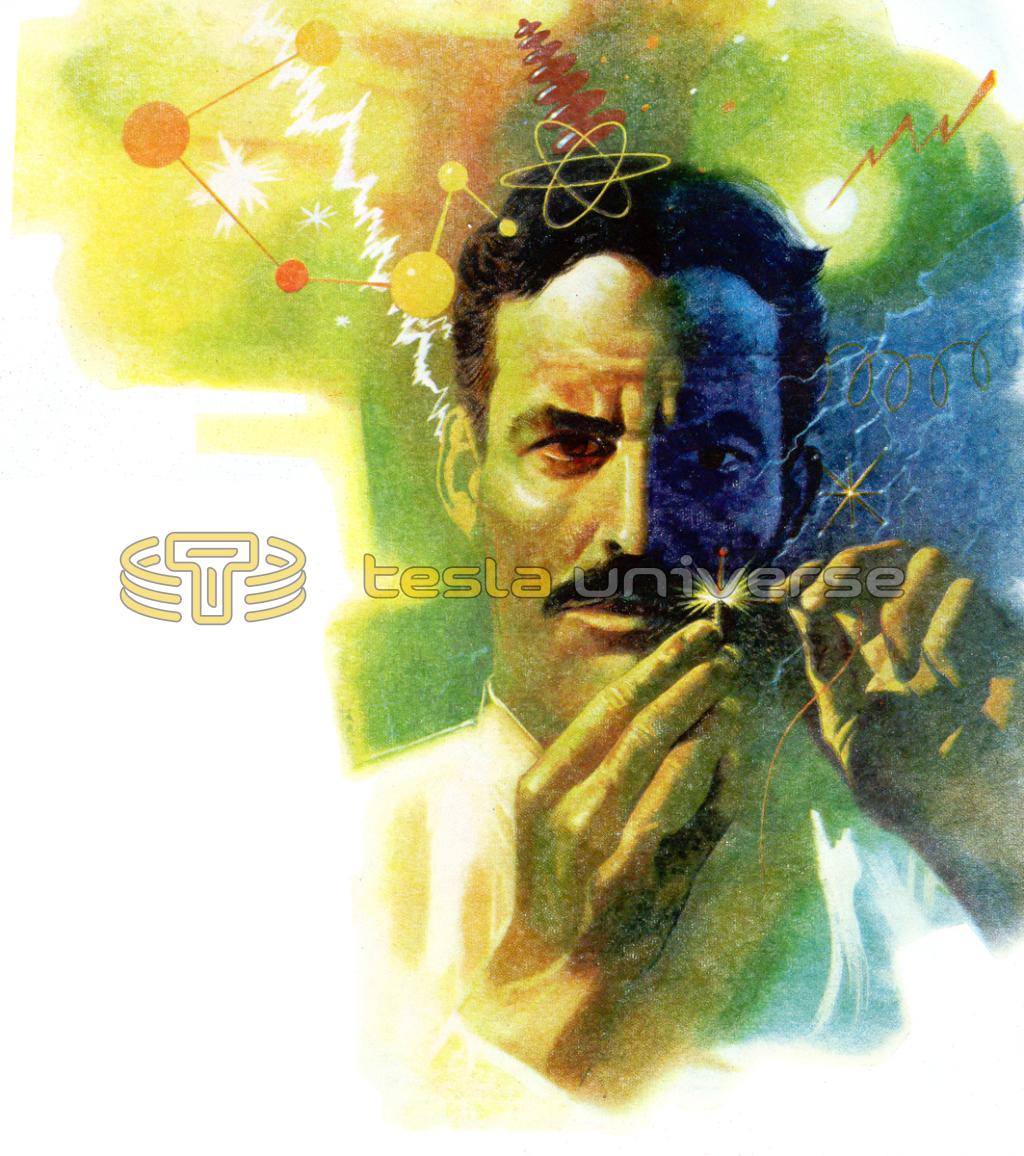

The Man Who Invented The Twentieth Century

Meet Nikola Tesla - genius in a top hat, father of modern electricity, lonely eccentric. He battled Thomas Edison and won - and he wired the world for progress

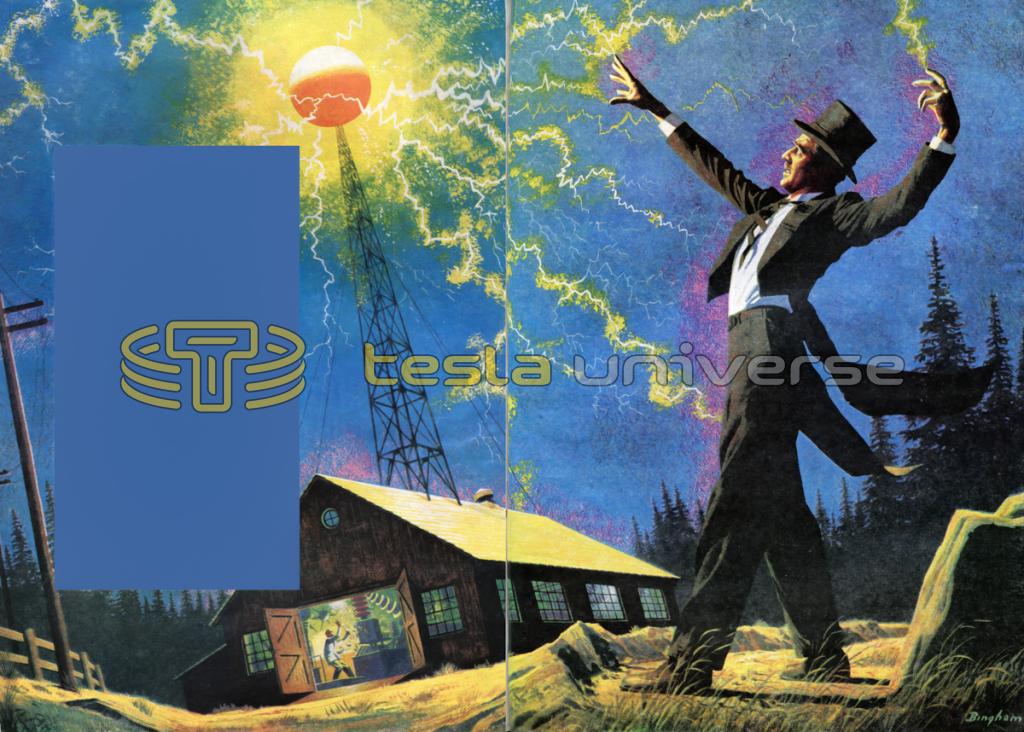

One summer afternoon in 1899 a tall, gangling man dressed in a cutaway coat and a top hat stood on the side of a hill in Colorado. His pale blue eyes were fastened on a 3-foot copper ball perched precariously on top of a slender 200-foot mast. Suddenly he shouted to his assistant in the laboratory below the tower, "Czito, close the switch, NOW!" In a moment a short hairlike spark darted from the copper ball. In another moment another spark, longer and thicker. The man in the top hat seemed pleased and rubbed his hands together with pleasure. In a few seconds the sparks became genuine bolts of lightning, 135 feet long and thick as a man's arm. As they flew into the air they were accompanied by tremendous, deafening crashes of thunder.

Just as the tall man was raising his hands over his head in an expression of triumph, the lightning abruptly stopped. He turned and rushed into the laboratory, enraged. "Open the switch again immediately," he shouted. "I did not tell you to close the switch."

But the switch was not closed-the wires were dead. Nikola Tesla's lightning experiment had knocked out the generator at Colorado Springs. Two miles away from the laboratory a huge cloud of smoke was billowing skyward, marking the end of the largest dynamo west of Niagara Falls.

This was 1899 and Nikola Tesla (pronounced Teshla), who had already invented the 20th Century, was now trying to invent the 21st. Incredible as it may seem this lightning experiment was part of a plan to set the earth in electrical oscillation so that a supply of energy would be available at all spots on the planet. You could just tune in the current like you tune in your radio and it would light and heat your home.

Way back in 1882, when Tesla was but 26 years old, he had invented the alternating current generator, motor and electrical transmission system that powers the world today.

At the same time he pioneered the radiation experiments that discovered X-rays, cosmic rays, radium and uranium. By 1892 he had invented modern radio, complete with vacuum tubes, a full four years ahead of Marconi's crude wireless set. The arc-light, the neon light, the carbon-button light, radio-controlled ships and submarines, the jet engine, and the Tesla coil - all came out of that period.

All are fantastic, and two are even more so. The carbon-button lamp was a miniature cyclotron with which Tesla produced brilliant light by bombarding a carbon button with electrons, 20 years before electrons were identified. The Tesla coil, the only invention still bearing his name, was to become the heart of all ignition and broadcasting systems. It was invented long before he or anyone else knew of ignition or broadcasting systems.

In his lifetime Tesla's inventions returned royalties amounting to some $150,000,000. Of this amount, one million was thrust upon him, and the rest he forgot to collect. Small wonder then that when he died broke in a lonely hotel room at the age of 87 in 1943, he was conveniently forgotten by a world that owed him everything. Success, as his arch-enemy, Thomas Edison, could have told him, is not based on what one contributes to society but on what one collects from it.

Edison was his arch-enemy because Edison was the high priest of direct current when Tesla was trying to convert the world to alternating current. But early in his career, when Tesla was unknown and his theories laughed at, he was forced into the position of having to work for Edison. Tesla came to New York, a poor young man, and got an interview with Edison who was already rich and successful. Edison offered him a bare living wage and an apprentice's job which was designing the automatic controls for his direct current generators.

Edison recoiled from Tesla's alternating current theories as from a basket of vipers but he knew a smart engineer when he saw one. He liked the idea of hiring the brains of a genius at the salary of a mechanic. Tesla would be able to eat and Edison would collect a few hundred thousand on Tesla ideas patented by no one less than Thomas Edison himself.

Insecure and lonely in the strange city. of New York, Tesla began to adopt the strange habits that were to mark him for the rest of his life. To his friends he was warm and outgoing but his friends were few. To most people he appeared as an aloof and rather eccentric scientist. At this time he lived as cheaply as possible in an obscure hotel room, eating the traditional crusts of bread that geniuses seem to favor, until he had saved enough. to buy a full dress suit. Then, as often as his salary would allow, he would go forth to Delmonico's or some other restaurant favored by notables, and there dine in solitary splendor. For an hour he would feed himself and his starved ego while he assured himself that he ate as high on the hog as the famous, and then he would return to his hotel room and his diet of crusts until he had saved enough for another splurge.

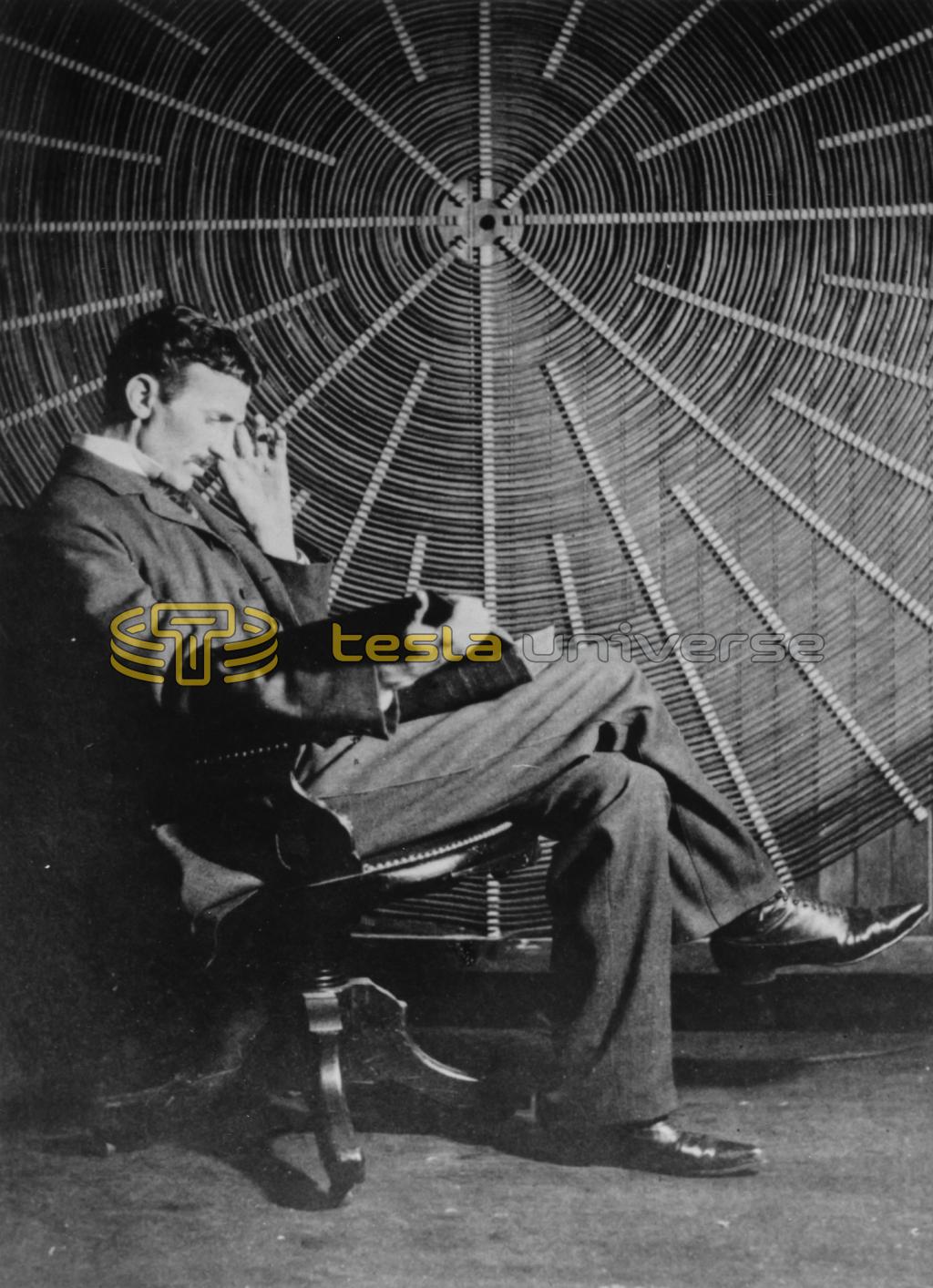

As an inventor, his great advantage lay in possessing a mental laboratory in which he could build the most expensive equipment without cash outlay. This remarkable mind was able to conceive not only abstract ideas but the machines themselves, down to the last details. He never needed blueprints because he stored these brilliant images in his mind where he had a permanent collection of working models.

He claims he never slept more than two or three hours. "My longest night's sleep," he once asserted, "was about as long as an Edison catnap." One project that occupied his mind was the invention of his alternating current high-voltage transmission system, complete with insulators, meters, and transformers, that would permit huge factories or a spinster's night lamp to operate from the main line.

At the Edison laboratory in lower Manhattan, Tesla could no more stop sparking brilliant ideas than he could stop breathing. In the course of his first year he turned out so many ideas for automatic controls, all patented by Edison, that he was grudgingly given a small raise. Then while designing a compact generator that could be installed in the hold of almost any steamship, he flashed another big idea.

"It's a short core dynamo," he shouted into Edison's good ear. "It has double. the efficiency of our best long core dynamo, and with my controls, it will run for years without attention." Edison's hearing was acute if an idea contained the rustle of big money. "Go ahead, young man," he said. "It's worth $50,000 if you can do it."

In the next few weeks Tesla rarely left the shop, and when he was through his new dynamo was even better than he had promised. Edison was delighted, and rushed off to file the patents on its various features. Tesla waited for his money, and waited, and began to feel a strange sinking feeling. With $50,000 he could set up his own shop, and it dawned on him that Edison might have thought of that possibility, too. He braced himself, and then went in to confront the old man in his den.

Edison couldn't hear a word, but as Tesla reached the arm-waving stage, the old man broke in suddenly. "The trouble with you foreigners," he said in words Tesla could never forget, "is that you have no sense of humor."

There was that note of cold dismissal, almost contempt, in Edison's voice, and Tesla was stunned. He ran from the room and all the way back to his hotel. "I was in a state of shock," he recounted later. "I couldn't leave my room for a week. I had no money, and to return to Edison was unthinkable. What made it unbearable was that my mind was alive with ideas, and there was no place, no place in the world I could take them. I felt that. the world had rejected me."

If the world had rejected him, Tesla decided he would reject the world. That was in the spring of 1886, and for a solid year Tesla worked as a common laborer, ultimately ending up as a ditch digger for the New York sewer department. His whole idea was to drive his body to such a state of exhaustion that his mind would be drugged and unable to run at night.

The world at large forgot him during that year and has almost forgotten him since his death. But his fame is secure so far as other scientists are concerned. "He was the Kilroy of the profession," admits atomic energy physicist Dr. Donald Gilbert. "Almost every time we think we are discovering a new field we come across a sign saying, "Tesla was here.'"

Tesla was born in the Serbian town of Smiljan, now a part of Yugoslavia, on July 10, 1856. Though his family and neighbors thought him a genius there was no sign of it during his first year as a college student. He enrolled at the Polytechnic Institute at Gratz, Austria, and began immediately to devote himself to a wild fling. He went to hell in the grand manner, drinking beer, chasing women, and consorting with evil companions. Fortunately it was his first and only such fling.

There were weekends during this year when he gambled from Friday night to Monday morning, pitting his meager allowance against the gambling skill of the best professionals in Gratz. Contrary to most stories of this kind, it was a lesson to the gamblers.

Did Tesla have extra-sensory perception? His gambling opponents often thought so. So easily could he read his opponents' cards and minds that he suffered pangs of guilt about winning. To this day at Gratz he is less famed for being its most distinguished undergraduate than for being the only sucker ever to return his winnings to the professional card sharks.

The big event in Tesla's college career was the arrival in the spring of 1876 of a professor who was preaching and demonstrating Thomas Edison's gospel of direct current electricity. At the same time Tesla had extended what was thought to be his extra-sensory perception to include a powerful influence over dice and the bouncing ball in the roulette wheel, and he was doing real well. Maybe that was what gave him the assurance to move against the great god Edison. But whatever it was, he moved. He denounced direct current, Thomas Edison, and all the amusing toys Edison called generators and motors.

For a young student of physics, that was tantamount to high treason, like denouncing the emperor. Electricity was in itself a miracle, and that a great man like Edison had been able to use it to light houses and streets in New York and Paris was a feat that bordered on the supernatural. The world had seen nothing like it, and great scientists joined the common people in staring in openmouthed awe at a glowing light bulb.

"And what do you suggest, Herr Tesla?" asked the professor.

"Alternating current," he replied instantly.

"Out! Get out of my class! I thought you were a smart student, but now I see that you are nothing but a fool." Tesla always liked to tell that story, using it each time one of his advanced theories was called crazy or far-fetched. "Since my student days I have been called crazy," he would say with relish, "but look at alternating current today. Look at radio. Look at my automatons that steer ships and operate machines better than men can. I was called crazy when I invented each. Gentlemen, if the time ever comes when one of my discoveries is not called crazy, I will begin to worry about it."

The brash young Tesla was not permanently expelled for his heresy, but he was made the butt of the professor's crude jokes for the rest of the year. Possibly the professor was justified. Electricity at that time was thought to be a solid force, pumped through a wire by a generator like water is pumped through a pipe. In Edison's system of direct current, the electricity left the generator through one wire, serviced the light bulbs and motors along its route, and-much like water tapped from a water mainwas then returned to the generator by a second wire. All the generator had to do then was give it a boost to keep the pressure up. Sweet and simple, and except that the pressure close to the generator was too high, and the pressure at the distant end of the wire-about a mile-was too weak, it was considered perfect by all but Tesla.

His own hastily made suggestion that alternating current was more practical than direct current was indeed laughable in view of existing knowledge. Alternating current generators had long been used in physics classes to demonstrate one of the many amusing ways in which electricity could be created. It was, for all practical purposes, about as useful as the electricity generated by rubbing a comb on a wool suit. A rotor was whirled around between a north pole and a south pole, creating a north-flowing current on the north-bound half of its spin, and a south-flowing current for the other half of the cycle. To return to the water analogy, it pumped water up, and then pumped it down on the return stroke, getting nowhere. No matter how you looked at it, a positive current cancelled by a negative current equalled zero.

But having committed himself, Tesla had to prove his point or-and this was more than his Serbian pride could bear - admit failure. He found two points in his favor. The whirling rotor of the alternating current generator required no direct contact with its poles, the current being "induced" to flow, just as the needle of a compass is induced to turn north without having to contact the magnetic pole. In that one point he could eliminate all the friction and wasted energy of the commutator in the direct current generator. And while the rotor produced no current at all when it was in the east and west positions between poles, it packed a terrific wallop at the peak of its north and south cycles, far greater than could be produced by a direct current generator of equal size.

The first fruits of his concentration on alternating current were disastrous. Bemused by the generator he was building in his mind, he forgot to apply himself in his gambling. In the fall of 1877, he tossed his tuition money on the green tables, and lost the works. He turned to his mother, and without a word this understanding woman went to one of her caches and staked him to another round. This time he concentrated, and in 48 hours of tense play, he piled up a small fortune. Then, to the complete horror of the professional gamblers who fully expected to be reimbursed for their losses as usual, he lurched off into the night without returning a pfennig.

That gambling session played an important part in history. Halfway home with his loot, he paused on a bridge to contemplate the water. This time the money did not bother his conscience, but he was dismayed by the fact that for 48 hours he had not given his motor a thought. Either he was to be a gambler, or the greatest man in the world, but he could not be both. So he swore off gambling for life, and then, carried away by his reformer's zeal, he swore off beer bouts, chasing women, the dueling at which he was expert, and all frivolities in general. And he never wavered. For the rest of his life he was to be a celebate monk serving his one god-Electricity.

Tesla finished his education at the University of Prague where he is remembered as the student who solved the most difficult problems in physics and mathematics in his head, and wrote down only the answers, usually in a flash. Then it was out into the cold world where Edison owned all the electricity, and there was no one else who could hire an electrical engineer.

For a while Tesla marked time installing telephones in Budapest, an art at which he became so adept that at the age of 25 he was promoted to chief in charge of everything. This was at a time when anyone of authority in Europe had to look the part-paunch, spade-beard, and cut-away coat-and skinny, beardless, boyish Tesla had to adopt an imperious manner to get his orders across that was to cost him many friends in later life, much though he tried to drop the habit. At the same time he proved how far he was ahead of his era by inventing a telephone amplifier to boost the weak signals of the Bell system. With his device, a telephone conversation could be heard throughout a large room, but for some obscure reason that persists to this day, people were horrified at the thought. Personal conversations in public, home or office could be loud or even shouted, but telephone conversations were regarded as sacredly secret, and his invention got nowhere. Fifty years later, he was to claim, it made millions for others as the phonograph amplifier that eliminated the tin horn and started the boom in recorded music.

During this period he set up a mental laboratory in which he worked constantly at his alternating current generators. It became a torment to him that left him so sleepless he prayed it would go away. "I would wake up," he explained to a reporter one day, "to the sound of it running in my sleep. But the instant I was awake, it would stop, and I would spend the rest of the night trying to make it run again. It is a terrible feeling, as though you are going crazy. Do not envy me, my friend. It is something I must go through with every discovery. If I don't have to go through it, I know my theory is no good, and I drop it."

Fortunately, there was a reliable witness present when at last the motor started up in Tesla's mind during a conscious period. He was Tesla's assistant at the telephone compay, a countryman named Szigeti.

As Szigeti was to relate often during his life, like a man who was present at a miracle, "We were walking through this park, when all of a sudden Nikki stopped. The sun was just setting, and he held up his hand as though he were commanding it. 'Watch me reverse it,' he said. You can strike me dead, but there was that about. him that made me think the sun would return to noon. Then he seemed to be pulling switches in the sky, and he said, Now! I have it running in reverse!' The sun was still there, and now I thought he was crazy. Then he started to talk, and I knew he was all right."

Tesla talked for an hour in the deepening dusk, reaching up now and then to pull an imaginary switch to illustrate a point. The motor he built in thin air was to prove perfect in every respect.

In brief, the machine he described in an hour of breathless talk was not one alternating current motor, but three-inone. His rotor would still be drawn to its north pole like the compass needle is pulled to magnetic north, but once there it would not stop, cancelled out by the opposite pull of its south pole. Instead, a north-northwest pole would draw it around to the west, a south-southwest pole would draw it south, and then the opposite poles of those three would induce it to complete the revolution.

As Tesla described his machine that night, it was both motor and generator. When fed electricity, it produced power; when powered by steam or a water wheel, it produced electricity. No longer would his fluid electricity be pumped back and forth, going nowhere. With three pumps working in synchronization, the fluid would be spun into a whirlpool of enormous pressure, and would reach peak power passing six poles instead of two. "At sixty cycles a second, you will never know when the positive flow ends and the negative flow begins. It will be just like a direct flow of electricity, but a thousand times more useful," he cried.

Seething with ideas and aware only that his brain held the discovery of the century, Tesla rushed off to Paris to lay his plans before the Continental Edison Company. It never occurred to him that Thomas Edison was coining millions of dollars on his direct current monopoly, and was quite happy with his fate. As he was to prove all his life, he was no business man, but his naive action in offering alternating current to the Edison company has no modern parallel, unless one can imagine an ad man asking Henry Ford II to endorse Chevrolets.

Edison's direct current system required an expensive and profitable-generator to service every couple of square miles. In Paris alone, scores of generators would be needed, and there was still all the rest of Europe to be electrified. And there was Tesla pleading that one of his alternating current generators, costing less than an Edison plant, would light all of Paris, and half of France to boot. Vigorously, Tesla pointed out that direct current could never get anywhere-that piping direct current into a wire was like piping water through a tube of blotting paper. "The higher the pressure, the more it leaks. But my high-voltage alternating current goes through so fast - zing-zing - that it can travel hundreds of miles before resistance can weaken it."

One or two officials were capable of grasping Tesla's blurted theories, and were properly horrified. Even if they bought his system for a few hundred dollars, as they could have done, where would be the profit if one Tesla generator could kill the sale of a hundred Edison's?

And so the idea lay unused for several years while Tesla came to New York, worked for Edison, and ended up digging ditches.

It was the lowest point in Tesla's life yet a valuable one. It taught him to talk common talk with common men, and one of these turned out to be a Western Union executive who had been caught in a company politics squeeze play. He wanted very much to get out of the ditch and back with Western Union, and when, one lunch hour over an onion sandwich, he heard Tesla reveal his bitterness over the Edison deal, he thought he saw a way. Western Union was not too happy over Edison's monopoly of electricity, and Western Union might be grateful to the man who could break that stranglehold.

So a few days later Tesla donned his slightly moth-eaten cut-away and took himself to the office of A. K. Brown, a Western Union mogul better equipped than most business men to understand the technicalities of his trade. Brown admitted later that he understood less than half of what Tesla was talking about, but that could have been because the 31-year-old repressed genius was scared to death, and raced through his explanations in Serbian, German, French, or English, according to the pitch of his excitement. But if Brown only understood half, it was more than enough.

It was an era in which business men made their own decisions without awaiting the verdict of a board of directors. A week later the ex-sewer-digger was installed in his own laboratory on West Broadway, two blocks from Edison's shop, and the battle of electricity was joined.

If European business men were afraid of a great man like Edison, the Americans were not. "The bigger they are, the harder they fall," was both a challenge and a slogan, and when Tesla, working from memory alone, produced a working model of his alternating current generator-motor, Brown knew exactly what to do with it. He cranked up the telephone, and shouted through it for George Westinghouse, demanding his immediate presence at the laboratory.

George was 42, impulsive, and so fabulously wealthy on his Westinghouse air brake for trains that a million dollars or so he considered as petty cash. What was more, he was brilliant, an inventor of considerable ingenuity, and he had a working knowledge of electricity. In two hours of conversation he recognized Tesla's genius, saw the merits of alternating current, and leaped ten years into the future when the whole world would be powered by Westinghouse alternating current.

"A million dollars cash," he offered. Tesla knew only that a hundred dollars was greater than ten dollars, but the neat roundness of a sum like a million dollars fascinated him. He contemplated it in silent admiration, and Westinghouse took his silence for hesitation. "Plus a dollar royalty per horsepower on all generators and motors sold," he added.

The final contract was drawn up in a matter of days, and it included a protective clause requiring Tesla's services for a year to iron out any bugs that might crop up in the course of commercial development of his system. It was a reasonable clause, but for Tesla it was pure hell. His system was perfect as he saw it, it was sold, and now he wanted to take his million dollars and go on to his big ideas. Instead, day after day, he had to go over the complexities of his system with commercial engineers who kept saying, "I understand that much, but -"

Tesla just was not built to work with subordinates. While they labored mightily to catch up on his old ideas, he was off on something else, and when he was called back to something he thought already accomplished, his impatience was noticeable, to say the least. In the end he reached a compromise with Westinghouse. For his freedom, he would release his rights to the dollar-per-horsepower royalty.

It was one of the most expensive gestures in history. No invention, and that includes the automobile and the flying machine, has ever captured public fancy and cold industrial logic the way alternating current did. Edison had been reap. ing his millions with the slow spread of steam-generated direct current, and thanks to Tesla's improvements had managed to enlarge the effectiveness of a generator from two square miles to ten. And suddenly there was Westinghouse covering hundreds of square miles at the same cost. Niagara Falls was harnessed, and its power went not just to Buffalo, but to New York City, Cleveland, Toronto, and all villages in between. Villages, incidentally, that could afford to tap a high tension wire, but could not afford an Edison dynamo. The horsepower in generators and an industry calling for more and motors reached fantastic heights. A most conservative estimate would be that Tesla tossed away more than $12,000,000 to buy his freedom.

He was to do it again and again, and he simply didn't give a damn. In the case of Westinghouse and the millions he harvested, Tesla got his satisfaction out of what George did to Edison. One minute Edison was king of power, and the next he was selling light bulbs, music and voices on wax cylinders, and a thing called the Edison flickers used to drive patrons out of the theaters between. vaudeville shows.

Edison fought back mightily, doing everything he could to discredit his for mer employe. His trouble was that he had very little to work on, but he used what he had. Sing Sing had discovered alternating current was a neat, clean disposer of felons when used in an electric chair, and Edison screamed mightily that the current that killed bad men was a menace to every man, woman, and child in the land. He wanted it outlawed, and he wanted it outlawed now and forever.

Tesla had one devastating retort. He invited the press to his laboratory, and there staged a spectacular demonstration in the course of which he picked up high-voltage wires with his bare hands, shot sparks into the air from his finger tips, and lighted bulbs in his teeth. The front page stories that followed made alternating current appear to be as harmless as rain water, which was hardly the case at lower frequencies, but Edison was forced to subside.

Tesla was now rich and famous. He was a celebrity, sought after by cultured. men and beautiful women, and he hardly knew how to handle his new role. He had been playing the part of the monastic devoté to electricity for so long that the habit of solitude was impe ble for him. to break.

Except at formal dinners Tesla always dined alone, and never under any circumstances would he dine with a woman in a twosome. He always wore formal attire and usually ate at either Delmonico's or the Waldorf-Astoria where he had special tables which were always reserved for him in secluded sections of the dining rooms. At each meal he had a huge stack of linen napkins beside him and wiped each piece of silverware clean with a separate napkin before using it.

He accepted few invitations, but every now and then he would be overwhelmed with some strange feeling of social obligation and then he would overdo it by throwing a banquet costing hundreds of dollars. When he staged a dinner he left nothing to chance in the matter of cuisine, service and decorations. He sought rare fish and fowl, meats of surpassing excellence, the finest in wines and liquors.

After such a banquet Tesla would take his guests down to his laboratory and dazzle them with weird lights and miniature thunderbolts. He had a flair for the dramatic and his laboratory was certainly a dramatic spot. Globes and tubes of various shapes glowed respléndently in unfamiliar colors. Sheets of flame issued from monster coils. Everything was there to amaze and delight his guests. And these were not toys but experimental devices for the new inventions that were always seething in his brain.

Once alternating current was established Tesla moved on to even grander conceptions. One of the most important of these was wireless transmission or radio. With Tesla's dramatic sense it was never enough to work out the theoretical basis alone. He always brought his inventions to the point where they were spectacular performers before he presented them to the public.

To stage his radio demonstration he took the great auditorium of Madison Square Garden. This was in 1898 when the Garden was still on Madison Square. He installed a large tank in the center of the arena and had his radio-controlled boat floating in it. Anyone in the audience could call the maneuver for the boat and Tesla, with a few touches on a telegraph key, would cause the boat to respond. His control point was at the far end of the arena.

The boat had an antenna, a radio receiving set and a mechanical brain that translated the radio signals and operated the boat. The demonstration actually included two inventions, radio and robots. It created a great sensation and made Tesla the popular hero of the day. But Tesla did not pause to capitalize on these remarkable developments. His fast-moving brain had already taken a further jump to a new and more amazing plan.

If radio signals could be transmitted without wires why couldn't the same thing be done with electric power itself? This was his great scheme for power broadcasting. The remotest farmer in the land would have but to erect an antenna. to light, heat and power his farm.

In a fresh frenzy of activity, he invented coils and condensers, and soon he had his Houston Street laboratory so energized that he could hang lighting tubes anywhere in the air, without wire connections, and they would bathe the whole shop with an eye-relaxing glow. Suddenly he was moved by an unusual concern. Back in 1896, experimenting in resonance, he had invented what he called a "telegeodynamic oscillator" that could produce vibrations of various frequencies. Like a violin played at a certain pitch, it would shatter wine glasses, and cause tables and chairs to dance, but Tesla had an idea that if he anchored it to the steel framework of his building, he could develop some really interesting frequencies. What he did not know was that his laboratory rested upon a layer of sand that spread for several blocks under lower Manhattan.

Long before his own building began to feel the effects of his experiment, that layer of sand began to quiver and then shake. Resonance was reached first in the water mains, and they began bursting. Then gas pipes in hundreds of tenements, lofts, and office buildings began to go. At police headquarters two blocks away, the massive red brick walls began to shake, the windows popped out, and then a broken water pipe released a flood of water through the ceiling.

In one of the most astute pieces of police work ever seen, a detective clawed his way out of the plaster shouting, "Earthquake, hell! It's that damn Tesla!"

Instantly a score of cops went pounding over waving sidewalks to Tesla's laboratory. One wall was partly demolished, and the front door was askew when they crashed in. Tesla was standing in a litter of fallen plaster, a sledge hammer in his hand, and in front of him was the demolished oscillator.

"You are too late, gentlemen," he said gravely. "The experiment is over."

They informed him that his experiment might be over, but that lower Manhattan would be a long time pulling itself together again. Fortunately, no one had been injured, and no fires had broken out in the explosive situation, so Tesla escaped with a light reprimand. It was with that reprimand in mind that he now surveyed his highly charged laboratory. To saturate the air still more, he felt, would be to expose congested New York to the risk of becoming the fused foundation of a cosmic lightning bolt. Thoughtfully he moved his laboratory to the wilds of Colorado, as already described.

Tesla was not allowed to get far with his idea of broadcasting electrical power through the air. His backers could see how wonderful such a system might bebut, after all, who would pay for it? Once the sky was charged with power, anyone could tap it with an antenna, and how could you collect the light bill?

Tesla did not ease their worries with his next experiment. He discovered a vast field of electricity at the earth's core, and at once conceived the idea of supercharging it with his giant coils. Any extra charge of electricity pumped into the earth's electrical field in Colorado would be instanly distributed all around the world, to be drawn off at will by users in any land and all the ships at sea. He had progressed in his experiments to the point where he could light a bank of 200 light bulbs plugged into the ground 26 miles away, when his backers gave up in despair. How could you collect the light bill if the customers could plug into power through any hole in the ground? With no more money coming in, Tesla was forced to return to New York.

The odd thing about that venture is that it was based on a multi-million dollar idea all the time. Dropped by Tesla and his backers was the Tesla coil he had used to charge both earth and sky. Salvaged by others, it went on to become the heart of all ignition systems, and the veritable foundation of radio, radar and television.

After he returned to New York backers like J. P. Morgan, John J. Astor and Thomas Ryan continued to stake Tesla with large sums through the next few years. He maintained an office near the Public Library at which he arrived every day promptly on the stroke of noon. He had usually been up most of the previous night. Tesla was one of those people who do their best work at night and are at some kind of disadvantage during the day. For this reason he always kept the shades in his office drawn so that no daylight came in.

As he entered the office he required that his secretary be standing immediately inside the door to receive him and take his hat, cane and gloves. The office, of course, had been open since 9 a.m. to take care of routine tasks. He had a reputation for being hard on servants, secretaries and even scientists on his staff. He was very exacting and precise in the demands that he made.

On the other hand he was also generous. If he had to keep his secretaries and typists overtime he would buy them a dinner at Delmonico's. If he ordered a servant around more cruelly than usual he would immediately compensate him with a handsome tip.

While this system worked reasonably well with subordinates it didn't work at all with equals and business associates. Tesla's main problem was his inability to work with others. "The trouble with Tesla," explained one of his backers wearily, "is that while he can control all sorts of power, no one can control him."

Tesla was himself to admit as much. One day a science editor pointed out to him that no less than four scientists had won Nobel prizes for developing ideas first announced by Tesla. "Yes, I know," Tesla said. "But they were old ideas. Many people told me they were worth millions of dollars if I would market them myself, but that meant going backward. In my head I had better ideas that were also worth millions, and I found them more fascinating. All these years I have been saying, 'The next one will make me rich,' but somehow the next one becomes the last one, and I never go back to it again."

In 1912 Tesla was himself offered a Nobel Prize under ironic circumstances. Unaware of the bitterness between the two men, the committee sought to honor Tesla for his work in alternating current, and Edison for his work in direct current. Aghast at even having his name linked with Edison, Tesla indignantly refused, and was immensely satisfied when the committee, unwilling to honor Edison alone, gave the prize to a Swedish scientist named Gustav Dalen. A few years later powerful friends had to drag him to accept America's highest scientific honor: The Thomas Edison Medal. "That inventor," he kept muttering, "that inventor."

Tesla should have gone off in a great cosmic explosion, but instead he faded away in obscurity, emerging once a year at his birthday party for the press. He always had something spectacular to offer -death rays, cosmic power stations, robots to do the manual labor of industry, airplanes held aloft by radio waves-and he always made his announcements sound logical.

From time to time industry would catch up to an old idea of his, and buy up a patent long since forgotten. Sometimes the money would arrive in time to save him from eviction, and sometimes. it wouldn't, in which case a few old friends would come to his rescue. Mostly, though, he found his companionship in the pigeons that came to his hotel window, and it was not unusual for him to have a nesting pigeon or two in his desk drawer.

Yet he was never lonesome. His mental laboratory ran with undiminished vigor to his dying day. So vivid were his mental images that his last announced dream was a plan to project the images to photographic plates by means of electric brain waves. Slower thinking scientists have already found the way to record brain waves. Who knows but what Tesla might have discovered a way to record his brilliant images?

He died on January 8, 1943, and with World War II in progress, the contents of his room were sealed until the Federal Bureau of Investigation could go through his papers. There were no notes of scientific value. Tesla kept all those in his head, and had taken them with him. It is probably just as well. Modern scientists will need another 50 years to explore the fields he actually did discover, and by that time they should be on their own.

- George Scullin

Illustrated by JAMES BINGHAM