Nikola Tesla Articles

Nikola Tesla's Mother: Georgina-Djuka Tesla (1822-1892)

The mother's loss grips one's head more powerfully than any other sad experience in life.

— Nikola Tesla, in a letter to Jack Morgan, Nov. 21, 1924

Nikola Tesla, the man who "invented the 20th century," has been declared, variously, as an Austrian, a Hungarian, an East European, Slav, Yugoslav, Croat, and a Serb - which he was by birth, heritage and his human consciousness.

Tesla's mother, Djuka, though always described accurately enough as an unlettered, but extraordinarily gifted woman, has been sometimes spoken of as a Croat. There was a tendency in the former Yugoslavia co look for unifying factors which would help bring its different nationalities closer together: thus, a certain political task fell on both the mother and son.

Djuka was born in Tomingaj (''Tomo's woodland" - so named after her great-grandfather), a daughter of Nikola Mandic (1800-63), a reknown Serbian Orthodox priest in Gracac, and a granddaughter of Toma Budisavljevic (1777-1840), a priest, who was also a military commander, a cartwright, and a fine bookbinder. She was the eldest of eight children. Her mother became blind when Djuka was 16, and she looked after her seven siblings, until her marriage to Milutin in 1847.

Djuka and Milutin Tesla had five children: Dane, Angelina, Milka, Nikola (1856-1943) and Marica. All three girls married Serbian Orthodox priests.

Nikola, the fourth child, was born on St. Vitus day, June 28 (OS), or July 10, according to the modern calendar, "at the stroke of midnight", during a summer storm. The village midwife, afraid of lightning, said, "He'll be a child of the storm", to which the mother responded, "No, of light."

Nikola was christened the very next day, by the priest from nearby Gospic, Toma Oklobztja; the godfather was Jovan Drenovac, a Captain in the Krajina army, also of Gospic. This baptism, within twenty-four hours of birth, with the priest coming to the house, instead of the child being taken to the church, is believed to have been due to the seeming poor health of the infant. Village lore also has it that the child's heart was beating on the right side of his chest.

There is no photographic likeness of Djuka.

Nikola Tesla wrote:

"My mother was indefatigable, and worked regularly from four o'clock in the morning till eleven in the evening. From four to breakfast time ... I never closed my eyes, but watched my mother with intense pleasure as she attended... to her many self-imposed duties.... After breakfast, everybody followed my mother's inspiring example... and so achieved a measure of contentment."

He also wrote, "I must trace to my mother's influence whatever inventiveness I possess... My mother was especially gifted with a sense of intuition... an inventor of the first order and would, I believe, have achieved great things, had she not been so remote from modern life. The dexterity of her hands was such that she could tie three knots in an eyelash, when she was past sixty."

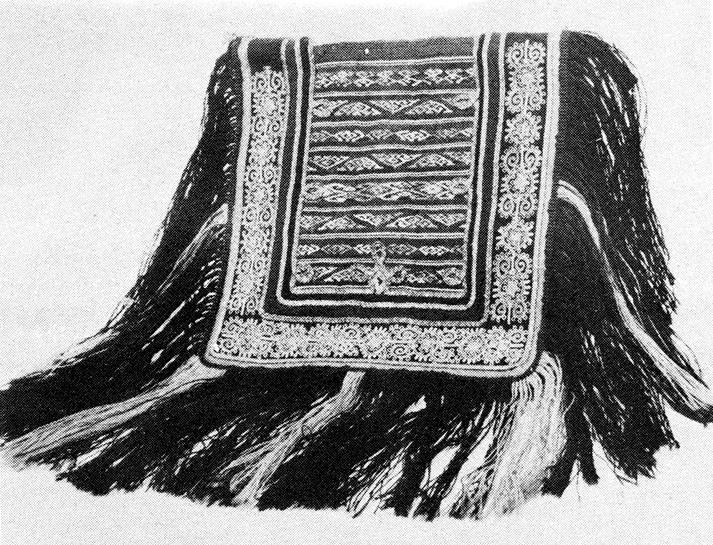

Djuka Invented several labour-saving devices and home appliances. Her exquisite home-spun, embroidered travel bag, which Nikola kept all his life, may be seen in the Museum in Belgrade (see inset picture).

Smiljan was a busy parish, and the Tesla home a busy household. Village women, who slow cooked over open hearths, and lit dimly their hovels with a flax string in callow in a hollowed-out turnip, came to see what the priest's wife had in the way of needlework, tapestries, embroidered towels and feathered pillows, came to seek patterns and dyes and pieces of fabrics, came to seek food in hungry years: garbed in perpetual black from their thirties on, they sat, and sometimes whispered, rearranging their kerchiefs, then wiping their faces with the hem of their long skirts. Rare was a family which had not lost men in wars, or children to disease.

Nikola's older brother, Dane, died in the summer of 1863, at the age of fifteen, following a fall off a horse.

Djuka woke up Nikola, and whispered, "Come and kiss Dane." Then she put him back to bed, and said, with tears streaming down her face, "God gave me one at midnight, and at midnight He took away the other one."

That year, the family moved from Smiljan to Gospic.

When he was in his early 20s, Nikola developed a passion for gambling, and at one point, in the summer of 1878, after he had lost everything at cards, Djuka gave him a roll of bills, and said, "Go and enjoy yourself. The sooner you lose all we possess, the better it will be. I know that you will get over it."

Milutin Tesla died in 1879.

Of Djuka's love for Milutin, the following anecdote has remained: some time after Milutin's death, a certain priest, Pepo Milojevic, who had wooed her, when they were both young, said, on meeting her, "Eh, Djuka, if you'd married me, you wouldn't now be a widow."

To which Djuka responded, "I would rather be Milutin Tesla's widow, than Pepo Milojevic's wife."

Djuka continued to live in the same apartment in Gospic, with her brother, priest Petar; who had succeeded his brother-in-law as the pastor of the Church of Great Martyr George. Nikola, who was to go to the United States in 1884, also helped support the family.

In February, 1892, Nikola was in Paris, giving a series of highly acclaimed lectures, when he received the following telegram from uncle Petar:

YOUR MOTHER ON DEATH BED. HURRY IF YOU WISH TO SEE HER ALIVE.

He cancelled further lectures, and rushed to Gospic.

"You've arrived Nidzho, my dear," Djuka said, when he came home, and the joy of seeing him worked the miracle of temporary recovery.

But not for long.

Night after night, Nikola sat by his mother's bedside, until he was in such a need of sleep, that on Good Friday, he was taken to a house two blocks away, to get some rest.

Nikola later wrote, "When I was alone in bed, I mediated on what would happen if my mother were to die. Would there be a disturbance in the ether?... I was sure that she would think of me to her last breath..... I struggled desperately against sleep and, with my senses sharpened by the darkness and stillness of the night, I watched intently .... Then nature prevailed, and I fell into asleep or swoon. When I regained consciousness, an indescribably sweet song filled my ears and I saw a floating white cloud in the centre of which my mother was reclining, looking at me with loving eyes, her smiling face illuminated by a strange radiance unlike ordinary light, and grouped around her were figures like those of seraphims. Spellbound, I watched the apparition as it passed slowly across the room and disappeared from sight. In that instant, a feeling of absolute certitude swept over me that my mother had just died and, sure enough, a crying maid came running who brought this mournful message."

Djuka died on Easter Saturday, April 3, 1892, and was buried the next day, beside Milutin, in the Jasikovac cemetery in Divoselo. Six priests officiated at the burial. There was a large funeral procession, and a multitude of wreaths, including one each, from: children, brothers and sisters, grandchildren, nieces and nephews, and the citizens of Gospic.

From Gospic, on April 21, Nikola writes to his uncle Pavle, in Varazdin: "I am immeasurably sad, but console myself the best I can. I had long anticipated this sad event, but the blow, nevertheless, was heavy. I always hoped that mother would live longer, because she was strong, and mine and my uncles' successes were a strength to her...."

Nikola raised individual tombsones of white marble, and of the same height and likeness, to each of his parents. On Djuka's stone was written:

DJUKA TESLA WJFE OF PRIEST TESLA

Whether Milutin's and Djuka's tombstones have been spared by recent wars is not known. Most clergy families in Lika were related by blood. All together, within the Mandic-Tesla families, between 1750 and 1941, there were 36 Serbian Orhodox priests. The Second World War found six priests serving in the parishes in Lika. One died of narural causes, while the other five were killed by Croat fascists, together with 530 Serbs of Smiljan. By now, most of the churches in which the Mandic and Tesla priests served, have been burnt down, or lie in ruins. Djuka Tesla's birth house in Tomingaj, although "under the protection of the state" from 1945-91, was allowed to decay, and may or may not still be standing.

D. Mrkich, 2003