Nikola Tesla Articles

Pictures from Outer Space

For years now, scientists have agreed that intelligent life exists in our universe. What has only recently come to light is that we have received PICTURES FROM OUTER SPACE

His name was Nikola Tesla, and he was already world renowned before the dawn of the electronic age. As inventor of an AC electric motor in 1888, his fame predated that of Marconi and Edison, whom he regarded as bumbling amateurs. Yet their names remain while Tesla's is all but lost in the dust of time. Still, it was Nikola Tesla who, a year before the turn of the century, set in motion a controversy that has been waged for almost seven decades since --communication to and from living, intelligent beings beyond our planet, our solar system, even beyond our galaxy.

Tesla, a Yugoslav electrical engineer, experimenter, and amateur mystic, immigrated to the United States and so captured the imagination of J. Pierpont Morgan, that the Scourge of Wall Street gave him financial backing for a venture that was to eventually make lasting scientific history. Tesla had a theory to the effect that the magnetic field surrounding the earth could be utilized to transmit energy from one place to another without the aid of wires.

In 1899, he set up shop in Colorado Springs, and with the aid of Morgan money constructed a 200-foot transmission tower and high-voltage equipment to feed it. In effect, the experiment, within its limited aims, was successful. Vast surges of electricity jammed into the earth lit up incandescent bulbs some 25 miles away from the tower.

But the success story may well have been more than that. Because Tesla at the same time was also boosting high-voltage impulses into his tower, transmitting them through the Earth's atmosphere - and farther - from a yard-wide copper ball at the top of the 200-foot tower.

However, the startling experiment was yet to come. Some of his equipment - crude types of radio receivers - was being used to investigate electronic disturbances in the atmosphere. One evening, weeks after he had proved his "wireless energy transmission" theory, Tesla was alone in his lab playing with the receivers. Suddenly, he picked up a sound, then a series of, as he described them, "electrical actions," that formed a determinable pattern.

Tesla was later to say for publication: "The changes I noted were taking place periodically, and with such a clear suggestion of number and order that they were not traceable to any cause then known to me. I was familiar, of course, with such electrical disturbances as are produced by the sun, Aurora Borealis and earth currents, and I was sure as I could be of any fact that these variations were due to none of these causes. It was a long time afterwards that the thought flashed upon my mind that the disturbances I had observed might be due to intelligent control."

And then the hooker that started the argument - "The feeling is constantly growing on me that I had been the first to hear the greeting of one planet to another."

The reaction of the scientific community at that time was immediate and scornful. He was labeled an eccentric, which, in effect, he was. His long-held beliefs in mysticism, in extrasensory perception, in spiritualism, were dragged out into the open and put on public display. Initially, he was merely the laughing stock of his intellectual brethren; later they were to call him "liar" and "fraud."

But that was back in 1899, 1900 and 1901. In the enlightened year 1966, we know that much has happened since the turn of the century that confirms Tesla's findings. Not only are we reasonably certain, despite the pall of secrecy thrown over the entire subject, that Tesla picked up signals of extraterrestrial origin, but that others have performed the same or similar feat several times over. It is no longer a joke. Some of our most brilliant scientific minds are busy at work searching the skies, probing the heavens, with giant transmitters and receivers, trying desperately to establish communications with civilizations outside this planet.

More than that, there is now a growing body of evidence that we can and are sending pictures into outer space. We know this is possible-and here's the best kept secret of the entire subject - because we have received such pictures.

That the whole matter has been shrouded in mystery and kept a fantastically deep-dark secret from the public both here and abroad, fed to it in only vague bits and pieces, can be chalked up to only one thing. The concept of interplanetary, intergalactic communications between ours and other, separate civilizations is so revolutionary that, if it were generally accepted, it might cause a worldwide panic. It could topple governments, go so far as to cut the ground out from under the world's great religions.

Just to give you some idea of how far the campaign for super-secrecy has gone, when Tesla died in 1943, the Federal Bureau of Investigation raided his home and removed all his papers. The official reason given at the time was that the dried up, bitter old man had been doing confidential defense work for the U.S. Government. Investigation proved otherwise. Tesla had been bedridden almost since the start of World War II, and was probably physically and mentally unequipped to handle sensitive material.

But the U.S. was not the only government showing dramatic concern about proliferation of the truth about interstellar communications. One of the earliest believers in signals from outer space was Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky, nicknamed "Father of the Russian Sputnik." As long ago as 1920, he wrote a letter to the Communist Organization of Young Technicians, in which he forecast: "In the near future short radio waves will penetrate our atmosphere and they will be the main means of stellar communications." On his death in 1934, his home was raided by the N.K.V.D. and all his papers bundled up, carried off to the archives of Aeroflot, the official U.S.S.R. airline. They remain there today under lock and key, and may be viewed only by members of a select group of Soviet space scientists.

Even though there is, in effect, a conspiracy of international proportions that attempts to hide the truth, enough facts have dribbled through the curtain of silence to establish three conclusions:

- That we have already received auditory signals from extraterrestrial civilizations;

- That, in addition, we have the means to communicate with those civilizations and are attempting to do so;

- And that we have received pictures - or visual communications - from outer space and know how such transmissions can now be accomplished from our end of the intergalactic network.

The evidence, old and new, has mounted up. The first confirmation for Tesla's postulate came a long time ago from the communications pioneer's arch rival, Guglielmo Marconi, who first made earthbound radio transmission a practical reality. By the end of World War I, Marconi had established radio stations on both sides of the Atlantic. It was these stations that, in 1920, reported the presence of strange, unidentifiable signals during Trans-Atlantic transmissions. Operators here and overseas described the signals as frequently taking the form of the Morse Code V, but hastened to add that at other times they sounded like some sort of code which they were unable to decipher.

Marconi was asked publicly if he thought the signals were extraterrestrial in origin, and he firmly answered, "Yes!" Because directional antennae had not yet achieved their present high degree of sophistication, Marconi conjectured in The New York Times of September 2, 1921, that the source of the signals was Mars.

Oddly enough, Tesla contested Marconi's claims, a fact that only served to fan the fires of competition between the two men. Marconi refused to extend the debate and there the matter rested for three years, when again public interest was piqued. This time the world was to get a real shocker.

By astronomical calculations, Mars and Earth would be at the minimum distance separating the two planets in August 1924, an event that happens every generation. In preparation for the big moment, the U.S. Government, at the behest of Dr. David Todd, Amherst College professor of astronomy, pressured owners of high-powered transmitters. throughout the world to shut down for five minutes out of every hour for a 24-hour period. During the dead time, Todd planned to zero in on Mars with a radio-camera, which was designed to record any radio signal on a photosensitive strip of paper.

Publicity attending the experiment was worldwide. U.S. Navy stations, as well as advanced receiver equipment in a dozen countries, were put on a 24-hour watch for mysterious signals. The suspense was killing even for the man in the street. Rumors were numerous, over back fences and on the front pages of some of the most reputable newspapers on Earth. Such was the hysteria that Marconi felt called upon to label the entire experiment "a fantastic absurdity."

After a delay of seven days, The New York Times finally broke the story. There were minor inaccuracies in the story (Todd's photosensitive strip was described as being 30 feet long when it was only 25 feet), but in essence it was correct. The strip, the Times said, "... discloses in black on white a fairly regular arrangement of dots and dashes along one side, but on the other side at almost evenly spaced intervals are curiously jumbled groups, each taking the form of a crudely drawn face."

The "face" has since been characterized as resembling that of an "oriental." Held at certain angles it looks like nothing more than an unidentifiable, amorphous mass. Was this a matter of coincidence and overactive imaginations, or was it the first recorded reception of picture transmission between planets, solar system or galaxies?

In 1962, almost 40 years after Todd's experiment, two scientists working for International Business Machines, C. D. Jackson and R. E. Hohmann, studied the Tesla, Marconi and Todd claims. With the customary objectivity of most men of their profession, in a paper delivered to the American Rocket Society, they refused to admit openly to seeing a face on Todd's tape. But throughout the paper there are frequent references to "images."

Nevertheless, whether the Todd tape contained a "face" or an "image," a picture from space seems to have been received on Earth in 1924.

The search did not end there. In 1931, Bell Telephone Laboratories put Karl G. Jansky to work rooting out the source of high-frequency static that was interrupting overseas radio communications. He set up an antenna network 100 feet wide at Holmdel, N.J., and began searching the skies. Two types of static were fairly easy to pinpoint and turned out to be caused and by nearby distant electrical storms. The third form, a frequent hiss over the loudspeaker system, was traced to the constellation Sagittarius at the center of our galaxy.

While Jansky's search did not in itself prove the existence of extraterrestrial intelligent beings and the fact that they were attempting communications with our world and others, it opened the way for further radio probes into the outer reaches of space.

By 1940, it was determined that just about the entire Milky Way was the source of radio transmissions that could not be accounted for - and have not been accounted for this day.

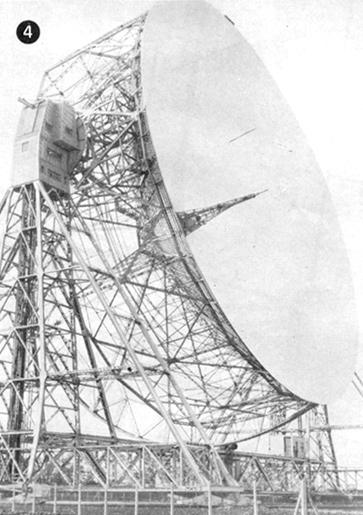

With the advent of WW II and the need for sophisticated listening devices, radar and other electronic research made a great leap forward. Here in the U.S., scientists and technicians perfected monstrous radar "dishes," or parabolic antennae, that became the prototypes for Earthbound investigation of space. At first, they were limited in size-an 84-foot-diameter model at Millstone Hill, in Westford, Mass.; two more at Goldstone 85-foot in the Mohave Desert; an job at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, W. Va. Across the Atlantic, the British erected a 250-foot model at Jodrell Bank. In Puerto Rico, an abandoned tracer mine served as the site for a fixed antenna 1,000 feet in diameter. Today, also at Green Bank, we have the world's largest steerable instrument, a 310-foot space detective to sweep the heavens.

In other words, following WW II, we began developing and putting in operation devices that were capable of deep space penetration, ones that. were more reliable, more directional. detection However, although the instruments were coming into their own, they were not fully exploited until several years later. Meanwhile, the mysteries of space life continued and were further compounded. The classic case, one that overshadows Tesla, Marconi and even Todd, occurred in 1953, and became known as the "KLEE phenomenon," sometimes the "KLEE thing." The story itself, never fully explained, kicked around for several years, finally received broad circulation through an article in Reader's Digest in 1958.

The mystery had its beginning on September 14, 1953, when for some unknown reason the identification letters of the Houston TV station, KLEE, turned up on sets throughout the British Isles. Londoner Charles W. Batley wrote the president of the Houston station, requesting an explanation of how, more than 10 years before Telstar, Trans-Atlantic TV was accomplished. Batley's letter found its way to Paul Huhndorff, an engineer for station KPRC-TV in Houston. You see, KLEE had been bought out in 1950 by KPRC, and in the three intervening years the call letters for the no-longer-existing station had not been broadcast.

How, then, had they suddenly flashed across the British TV sets three years after their last transmission?

The case was further complicated several years later when, in 1962, a Milwaukee resident again viewed the call letters on her own set during what she first assumed was an afternoon soap opera. She might have thought nothing of it had it not later turned out that she was watching the program on a channel which is not used in Milwaukee.

Dr. Frank D. Drake, associate astronomer at Green Bank's National Radio Astronomy Observatory, was asked by Huhndorff to investigate KLEE. Drake made no bones about his conclusions-he labeled the "KLEE phenomenon" a hoax. At the same time, he noted one very important fact about KLEE that made it so reasonable. And that was that most scientists have come to assume that the accepted procedure for letting extraterrestrial civilizations know that you have received their transmission is to duplicate that transmission and send it back to its source.

Is this what may have happened in the case of the mysterious KLEE call letters?

One answer may lie in the recent discovery of Dr. Bernard M. Oliver, Vice President for Research and Development of Hewlett-Packard Co., producers of electronic measuring instruments. Speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science this past January, Dr. Oliver said that emissions, or transmissions, from Earth that have the best chance of being picked up by extraterrestrial beings are those of our ultra-high frequency (UHF) television stations. They sweep the heavens every day, and aim themselves at the most far off stars. They are capable of reaching out to a distance of 200 lightyears, within which there are some 80,000 known stars, each with its own solar system much like ours.

"Clearly," Dr. Oliver said, "we have already revealed our existence to any race intelligent enough to search for us with properly designed receivers."

However, scientists point out there are still a few holes in the argument if one attempts to apply the Oliver report to the KLEE case. First of all, the late lamented station, KLEE, was not a UHF operation. Furthermore, there is the short three-year lag between KLEE's last transmission and the time it was picked up on British sets. If an advanced civilization received the call letters and sent them back, the transmitter would have to be located within our own solar system. While there may be life of sorts on the other planets around our sun, it is highly unlikely that it has advanced to the point where it could receive and transmit anything like the KLEE call letters.

Or has it? This is the question that still disturbs many astronomers.

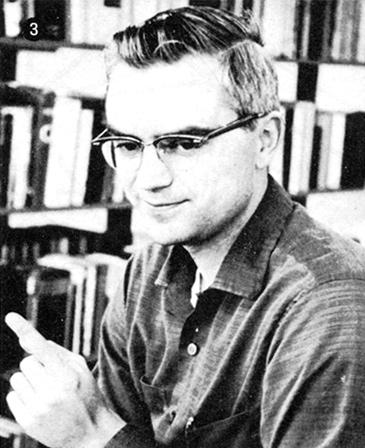

Probably the first concentrated effort to establish communications with life on other worlds had its beginnings in 1959. The aforementioned Dr. Drake proposed to his superiors that they use the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's 85 foot "dish" at Green Bank to listen in on the heavens, not just for one day or one week, but for an unlimited time. With permission granted, Drake called his experiment "Project Ozma." Drake chose as his target two stars that seemed like good subjects-Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, both some 11 light years away. On April 8, 1960, was ready to be put into operation. Drake and his assistants aimed their 85-foot scoop first at Tau Ceti and picked up nothing out of the ordinary. Later the same afternoon they switched targets and tracked Epsilon Eridani in broad daylight, using preset computations to follow their target.

It was only a matter of minutes before they began receiving an exceptionally strong signal-a series of rapid pulses numbering eight to the second. They were uniformly spaced, so precise that only an intelligent organism could have been making them or causing them to be made.

To make certain that the pulses were not emanating from an earthly source, the decision was made to shift the "telescope," or radio antenna, off the target. If the signal subsided when the scientists did so, they could be reasonably certain that Epsilon Eridani was the source. But just as they were about to de-zero the antenna, the signal stopped.

Two weeks later, the signal was picked up again, and this time the shift was made. However, the signal failed to fade when the antenna was steered off its target. The signal, whatever it was, came from someplace on earth.

The search went on throughout May, June and July, and while the pulses reappeared on several occasions, no reliable transmissions were picked up from either of Drake's targets. Finally, Project Ozma was abandoned because the telescope was needed in other experiments.

It did, however, serve one purpose: It legitimized serious research into the claims set down by Tesla, Marconi, Todd and other proponents of interstellar communications as an actuality.

The year that saw the aborting of Project Ozma also gave rise to research by astronomers at the California Institute of Technology, the Radio Astronomy Observatory at Jodrell Bank, England, and Cambridge University, England, all of whom singled out the solar systems of CTA-21 and CTA-102 from other radio sources in the heavens as worthy of further investigation. Both, it appears, have strong and distinctive microwave transmissions.

A year later, in 1961, Sergei Loriniev, a Soviet radio astronomer, claimed to have picked up distinguishable radio signals from the CTA-21 and CTA-102 sources. Also in 1961, a conference of world famous scientists was convened at the Green Bank observatory to, in the words of its organizer, J. P. T. Pearman of the Space Science Board of the National Academy of Science, ". . . examine in the light of present knowledge the prospect of existence of other societies in the galaxy with whom communications might be possible; to attempt to estimate their number; to consider some of the technical problems involved in the establishment of communication; and to examine ways in which our understanding of the problem might be improved."

The gathering was kept as hush-hush as a meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, except for the information that those attending estimated that "a goodly number" of the solar systems in the Milky Way had planets in them that could sustain an advanced form of life.

Since that time a more exact figure has been arrived at on the basis of present knowledge by Dr. Stephen H. Dole of the Rand Corporation. He notes there are an estimated 135 billion stars in our Milky Way, but that many are too large or too small to have planets that could support life. Accounting for all contingencies, Dr. Dole concludes there are 640 million planets like Earth in our own galaxy-and there are literally billions of galaxies in the universe. As for the existence of intelligent life, we can only guess. But on the basis of only one life-sustaining planet out of every million so-called "Earths," we can conjecture at least 640 intelligent species other than ourselves in our galaxy alone.

Now that it is fairly well established that some form of communication, both audible and pictorial, has been received from certain numbers of these extraterrestrial bein; can we reach them? Until quite recently our range of action was seriously limited, not by our capabilities as much as by our ignorance. A few years ago, world scientists estimated we could send out detectable radio transmissions perhaps 10 to 20 light years and no more. As a result, laser beams were explored as a possible medium of communication, but they were soon discarded when it was understood that dust in space would cut down their ability to penetrate beyond several light years. However, now we learn from Dr. Oliver that we are indiscriminately spilling our UHF television signals to distances of 200 light years and accomplishing this without even trying.

So, it is really academic to ask if we have the technological know-how to send our messages far enough out into space for them to be received by our counterparts on other worlds. The problem lies in getting our message across to the beings at the business end of the transmission.

Remember, they will not speak our language, have no knowledge of our alphabet or symbols, never heard of Morse Code. Thus, we must develop a code that permits us to communicate with them in the easiest manner possible for them to comprehend. According to Martin Gardner, writing in the August 1965, issue of Scientific American, "All experts agree that messages had best start with simple arithmetic. One assumes that units can be counted by any type of intelligent creature, and that arithmetical laws are uniform throughout the galaxy."

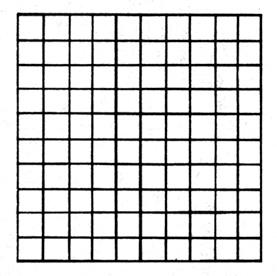

Mr. Gardner, who writes the magazine's "mathematical games" department, devised the following two-character, 100-symbol message as a simple example of the kind of message that could be sent (the zeros as radio impulses of long duration, the ones by impulses of short duration):

0000000111

1111111101

1110000111

1010000000

0000000000

1010110101

1010100101

1100110111

1010100010

1010110010

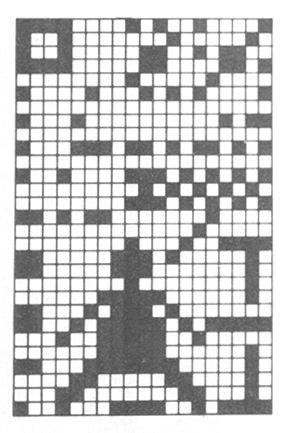

The fact that there are 100 symbols would suggest to the receivers they are going to be dealing with something much like the 10 x 10 crossword puzzle matrix shown here:

Without telling you what the message is, try working it out for yourself. Just darken every box that corresponds to the numeral 1 and you will get the message, which will consist of a picture of the object and the English word for it.

Dr. Frank Drake has devised a somewhat more complicated message using the same two-character principle, but this time extending the number of symbols to 551. The result is the filled in message as it appears on page 47 of this issue of Saga. Drake sent the message in symbol form to many of his colleagues in the scientific world for deciphering. To make it even more complicated, the message is not one that we would transmit to other worlds, but a hypothetical one that might be received by us from extraterrestrial beings. According to Drake, while a few of his associates deciphered the entire message, most of the scientists broke down those portions that had to do with their respective specialties, and fell short on the rest of the message. Actually, the message was designed at a level of difficulty that would permit a group of scientists to work it out in about a day's time.

Interpreting this finished product is considerably more difficult than laying it out in graphic form. What the receiver would first have to know, and probably would spot pretty quickly, is that there are 551 symbols. From there he should reason that there are only two factors that can be divided into 551 - and these are 19 and 29. Since these are prime numbers, right away he should get the clue that the message is two dimensional, as shown on page 47. With a minimum amount of trial and error, he could then lay out his 19-box-by-29-box matrix and start filling in either the ones or the zeroes, in this case the ones if he is to arrive at a correct pictorial representation of the message.

Now, while the result may look like Greek to most of us, there is a tremendous amount of information about the sender contained in the message for a group of qualified scientists.

For one thing, take the figure at the bottom. This would be the sender. We can tell he is manlike, a primate, has a heavier abdomen than earthlings and more widespread legs. Note, too, his head tends to come to a point. All these facts would suggest an important fact about his planet-that the gravitational pull there is considerably greater than on ours.

Next, look at the large square in the upper left-hand corner, beneath which are strung out nine smaller forms along the left-hand side of the message. This is crude, but accurate representation of the being's planetary system. Reading from top to bottom-a sun, followed by four small planets, an intermediate size planet, two large planets, another intermediate size planet, and at the bottom another small planet.

Amateur chemists may recognize the two groups in the upper righthand corner. They are schematic drawings of the carbon and oxygen atoms, which is the creature's way of telling us that his biochemistry is based on the carbon atom-just as ours is. Also, like us, oxygen is his oxidizer.

From here on out, the puzzle becomes more complicated, as does its explanation. Without boring you with the scientific explanation, the group of symbols to the right of the four minor planets and the fifth planet represent the first five numbers of our numbers system in a modified form similar to that used in computers. Further, it gives the expert clues about future transmissions, including how to look for words.

The group off to the right, below the atoms and above the squat being, are also numbers with involved interpretations. Note the diagonal line aimed at the creature. Leaving out all the scientific detail, it is sufficient to say that a good decoder could determine from this group that there are seven billion such creatures on the home planet, the fourth small planet from the top. Also, he has told us that he has reached a higher level of space travel than we and at the time of transmission had 3,000 creatures on planet three, and an exploratory group of 11 creatures on planet two.

The group of three figures off to the right of the creature, using a measurement that is common to both him and us, tells us his height is 31 wavelengths.

Finally, just not to waste space, he has crowded in underneath his body a symbol for a word, probably the word he will use in future transmissions for himself.

The reason for jamming as much information as possible into what would ordinarily be a very short message is fairly obvious. Interstellar communication is hardly the same as picking up the phone to tell your wife you'll be home late for dinner. Here, communication is almost immediate. Across the vast reaches of space, a message might take a decade, even centuries, to travel from sender to receiver. There is no time for chitchat when a message moving at the speed of light could very well take a lifetime to reach its destination. In Project Ozma, if Drake had really picked up an extraterrestrial signal from Epsilon Eridani, one of the nearest stars to our planetary system, he would have been listening to impulses that were 11 years old at the time of their arrival on earth.

Todd's crudely drawn "face," assuming it didn't originate on Mars, may well have been that of a creature that was already extinct on his home planet by the time his features were halfway to their goal.

Obviously, the vast time-lag between sending space messages and receiving answers doesn't seem to bother either creatures on other worlds or Earth scientists. Of course, both would like to make direct physical contact with the other, and with further technical advances, today's wish may eventually father the actuality. For the present, however, our space probers have taken a lesson from extraterrestrial beings who have contacted us via sound and picture. They are contenting themselves with the hope of merely telling their neighbors in distant space - "Look, fellas, I'm here!"