Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla - Inventor Ahead of His Time

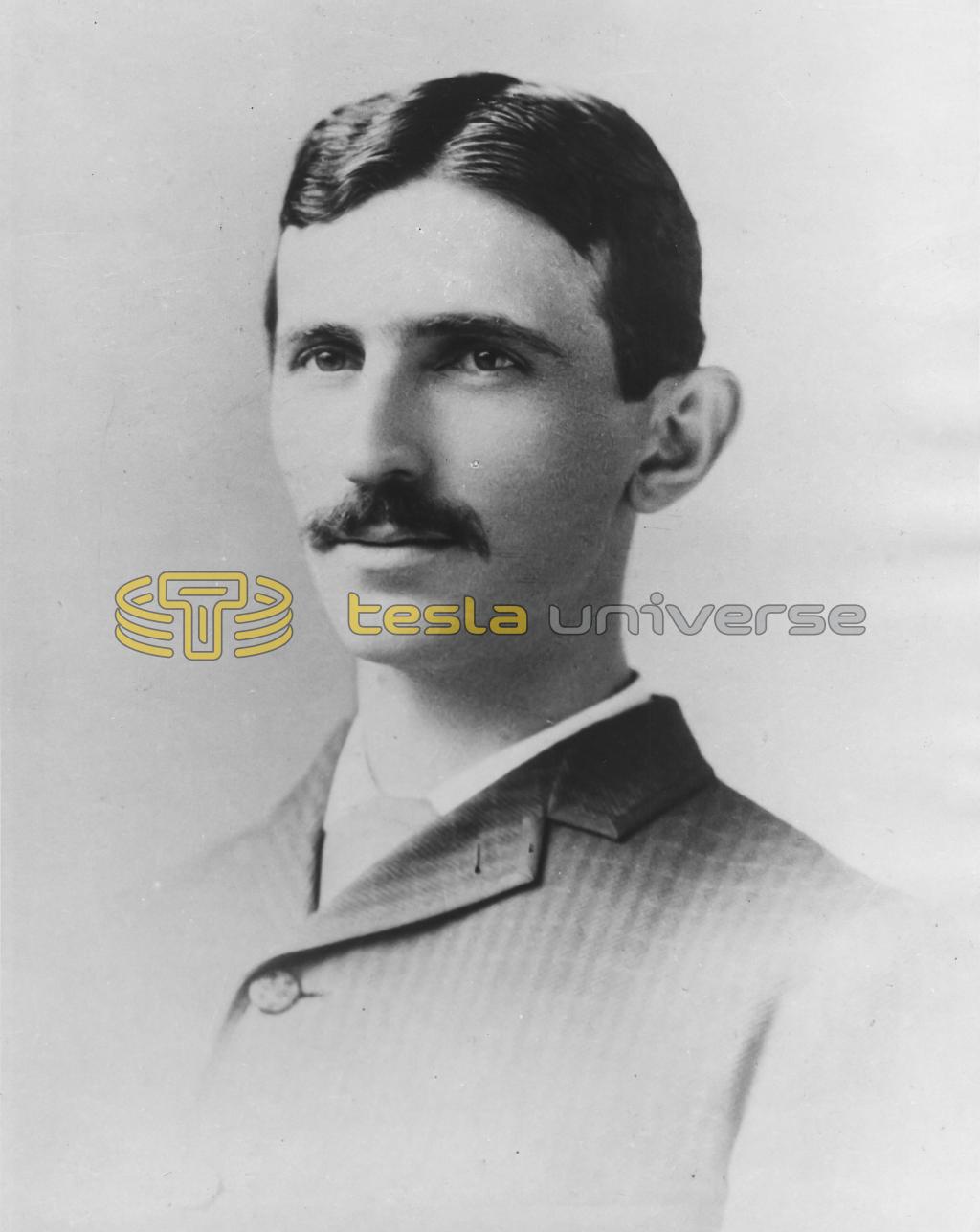

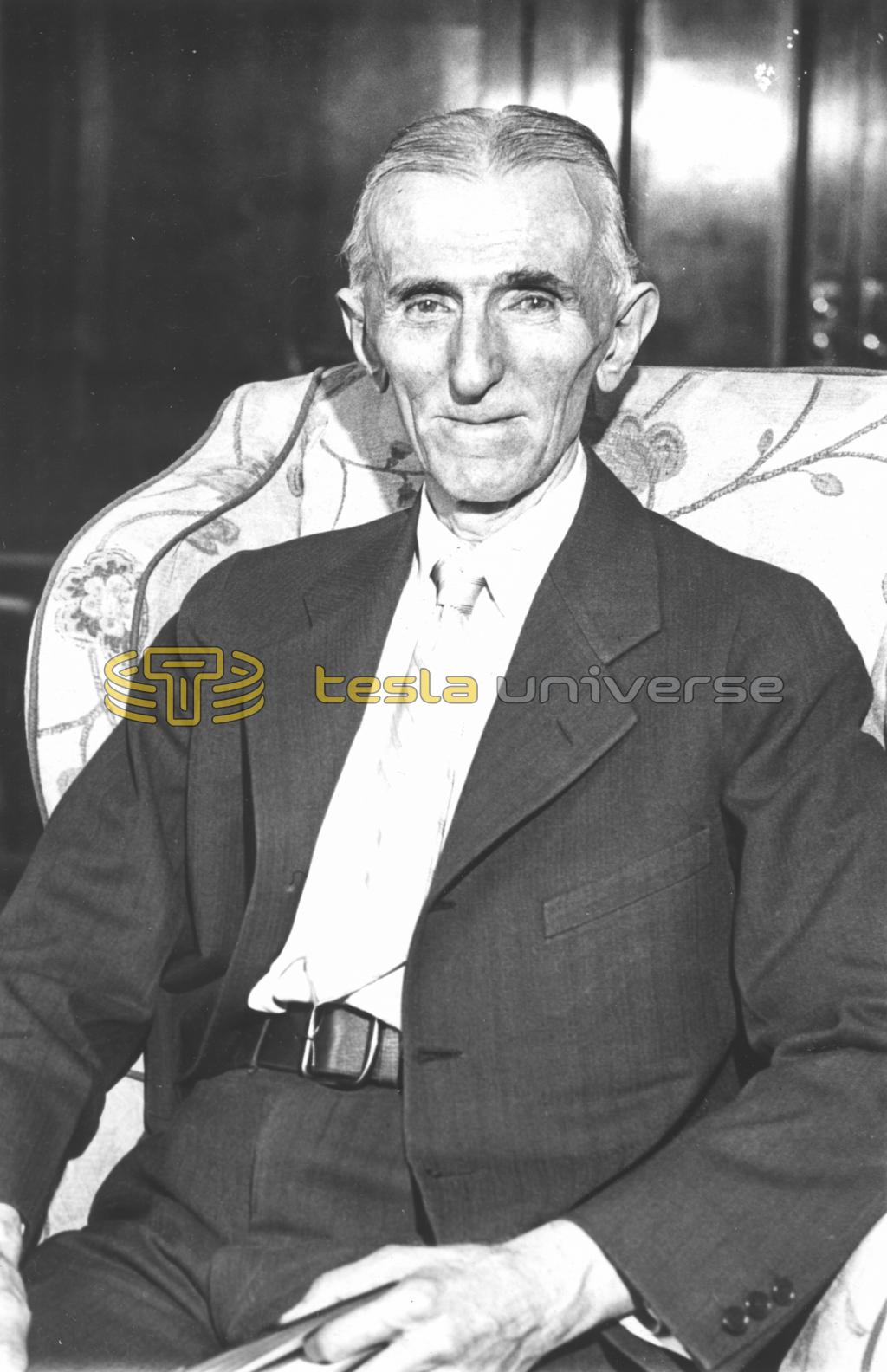

Portrait of an eccentric genius, born 100 years ago, whose inventions ushered in the electronic age.

The centenary of the birth of Nikola Tesla, one of the most man who probably did more than anyone else to introduce the electronic age. A memorial to Tesla was recently unveiled in New York City, where he spent most of his life and did his most famous work; the American Institute of Electrical Engineers held a session honoring his memory; and several science magazines I devoted articles to him.

Despite this recognition, an excellent full-length biography by John J. O'Neill and the formation of the Tesla Society, which has published an extensive bibliography of writings by and about him, Tesla remains little more than a name to the American public. Surely he is not so well known as Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell or even Charles Steinmetz, though many scientists I would rank him above these inventors.

This is an undeserved fate for a man who discovered how to use the alternating current that powers modern industry; who conducted pioneer experiments in fluorescent lighting, radio communication, radio remote control, robots and high-frequency heat therapy and who invented dynamos, transformers, induction coils, condensers and arc and incandescent lamps. Scores of his inventions, indeed, are yet to be utilized.

Nikola Tesla was born July 10, 1856, in the Austro-Hungarian hamlet of Smiljan, now part of Yugoslavia. His father was the village pastor and something of a poet. Nikola's mother, a member of a cultured family, never learned to read and write because she had assumed most of her blind mother's heavy duties at home and was too busy; nevertheless, she created many labor-saving devices for her household, and could recite from memory thousands of verses of Serbian poetry and long passages from the Bible. Nikola himself had a photographic mind. He found it easy to learn German, French, Italian and (eventually) English.

None too robust in his youth, he nearly lost his sight from too much reading, and barely survived several serious illnesses. He attended college at Carlstadt in Croatia, where he was so greatly impressed by the demonstrations in physics that he decided to make electrical engineering his life work. His father thought Nikola too frail for this career, but finally relented.

In 1875, at the age of 19, Tesla went to Gratz, Austria, to study at the Polytechnic Institute. During his second year there he watched the operation of a piece of electrical equipment, a Gramme direct current machine. Why not use alternating current, Tesla suggested, to eliminate the commutator, where so much sparking took place? The professor scoffed at the idea, comparing it to a perpetual-motion scheme. But Tesla kept on thinking about the problem during a year of studying mathematics and physics at the University of Prague, and afterward while working on telephone installations in Budapest for the Hungarian government. His mind, with its unique visualizing powers, became a prodigious storehouse of textbooks, formulas and equations - even logarithms.

One late afternoon in February 1882, he was walking in a Budapest park when the solution suddenly occurred to him in a vision: The rotating magnetic-field principle would operate an alternating current motor! In the next two months he worked out in his mind every phase of the revolutionary operation, constructing mental images of the design of dynamos, motors, transformers and other apparatus necessary for a complete AC system.

Later, in Paris - where Tesla was a trouble-shooter for the Continental Edison Company - his attempts to sell his invention were unsuccessful, even though the model he built worked just as he had imagined it would. No one else could foresee the machine's unlimited commercial possibilities.

Hoping that Edison himself would help him, the tall, handsome Tesla, now 27, arrived New York in 1884 with four cents in his pocket his money and baggage had been stolen just before he left Europe - and a letter of introduction to Edison. The latter gave him a job, but though Tesla proved himself competent, the arrangement lasted less than a year. The methods and temperaments of the two men were fundamentally different: Edison worked by trial and error; Tesla tried nothing which he had not previously thought out to the last detail. Edison attracted brilliant associates, delegated responsibility to them and stimulated their best efforts; Tesla was a lone wolf, self-reliant, secretive. More important, Edison was committed to direct current, which was used in the incandescent lamps he invented and lighted. He saw no future in alternating current and refused to listen to Tesla's ideas about it.

The darkest year in Tesla's life began in the spring of 1886, when he was forced to work as a common laborer - the only job he could get. Finally, however, he persuaded a few men to back him, and in April 1887 he opened a laboratory in Manhattan. Then suddenly his fortunes changed: His polyphase AC machinery was built, tested and patented before the end of the year. On May 16, 1888, he delivered a classic lecture before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, and in the same year George Westinghouse, Edison's competitor, paid Tesla $1,000,000 plus royalties (which Tesla generously waived later, when Westinghouse was in financial difficulties) for the patent rights to his motor. Considering the number of patents involved and the use they were put to, the price was cheap.

Money was never Tesla's main interest. Indeed, after a disagreement with Westinghouse engineers, he turned down an offer of $24,000 a year, one-third of the net income of the Westinghouse company, and his own laboratory. He could have made a fortune. if he had wanted to exploit even a few of his lesser inventions. It is estimated, too, that his waiver of the royalty provision of his contract with Westinghouse cost him $12,000,000.

The 1890s were Tesla's palmiest period. He could now concentrate on research, and his spectacular experiments with highfrequency and high-potential currents astounded engineers. Universities and learned societies of two continents begged him to lecture. In London and Paris, where he spoke before distinguished scientists, he was greeted as a hero. New York dowagers constantly entertained the dapper, eligible bachelor, but no woman ever played an important part in his life. Inventors, he once said, were too intense and passionate to give themselves to women; if they did, they would give all and would have nothing left for their work. It has been said that he was the only man who ever picked up and returned, without a word, a handkerchief dropped by Sarah Bernhardt.

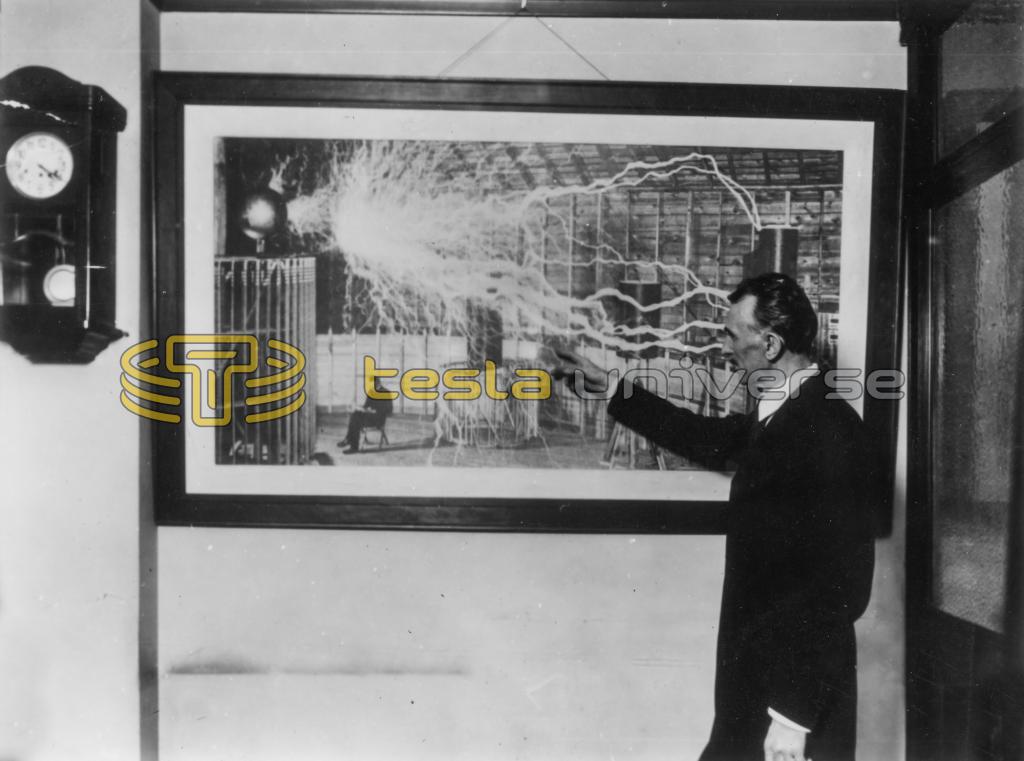

Like the "divine Sarah,' Tesla had a flair for the dramatic. He liked to entertain his guests by taking them to his laboratory and performing fantastic feats of flame and color with his grotesque machines. One of his favorite devices was to permit hundreds of thousands of volts of electricity to pass through his body and light an object in his hand without harm to himself, of course. Yet he had a healthy respect for electricity, and when working with potentially dangerous circuits he always kept one hand in his pocket so that the current could not pass through both arms and strike the heart. In his entire career he was injured only once.

To conserve time for research, Tesla eventually curtailed his social activities and led an increasingly solitary life. His idiosyncrasies became more marked. Because of his germ phobia, for example, he always discarded gloves after wearing them for a week; he used handkerchiefs and collars only once. At dinner, which he almost invariably ate alone, he demanded two dozen napkins, with which he cleaned each dish and piece of silverware. carefully avoided shaking hands with anyone.

He shunned coffee, tea and cocoa, which he considered harmful, but drank whiskey, believing that it gave him energy and prolonged his life. Prohibition, he remarked, would prevent him from living longer than 130 years. He claimed that he never got to bed before 5 a.m. or slept more than two hours a night.

Later, when he used an office during the day, he required that all the shades be drawn because he felt he did his best work after dark. The only time he allowed them to be raised was during a lightning storm, when he would lie on a couch near the open window, talking excitedly to himself - perhaps envying the power of nature.

Tesla's two greatest moments of triumph came in the 1890s. In 1893 the public had its first look at polyphase alternating current, when Westinghouse used it to light and power the Chicago World's Fair. Three years later Westinghouse and General Electric (Edison's old company, now won over to AC), working together and using Tesla's system, completed the gigantic project of transmitting electric power from Niagara Falls to Buffalo, a distance of 22 miles. Edison had been able to deliver direct current over a distance of only one mile. The age of mass production based on cheap electricity had begun, thanks to Tesla.

Meanwhile, on the night of March 13, 1895, just when he was about to make an important demonstration of wireless communication, a fire destroyed everything in Tesla's uninsured laboratory: apparatus, records, papers, mementos - the work of a lifetime. It practically wiped him out. But financiers came his aid, and within a few months he had set up another laboratory, though he turned down an offer which would have brought him. the full support of J. P. Morgan. Tesla was too absorbed in his inventions to worry about future needs; eventually, he thought, he would make the millions his ideas were worth.

Throughout the rest of the decade Tesla concentrated on wireless communication. By 1890 he had invented the first electronic tube designed for use as a detector in a radio system, the forerunner of the modern detecting and amplifying tube; now he succeeded in constructing a transmitter along with a receiver that was sensitive to its signals over a distance of 25 miles. Patents he obtained in 1897 contain descriptions of all the basic. features of radio broadcasting and receiving circuits in use today.

His ideas and their practical applications were seemingly inexhaustible. One of his most neglected inventions, still unused, was a carbon-button lamp which gave 20 times more light, for the same amount of current, than Edison's incandescent filament lamp. And Tesla's discovery of high-velocity cosmic rays anticipated a whole new area of research which would culminate 30 years later in the work of Millikan and Compton.

Tesla also conducted pioneering experiments with mechanical vibrations. One of these produced a panic in the neighborhood of his laboratory and almost resulted in a catastrophe: His oscillator-induced vibrations shook all the surrounding buildings so violently, knocking out chunks of plaster and shattering windows, that people streamed out of them, fearing an earthquake. Familiar with the strange noises that were always emanating from Tesla's laboratory, police officers from headquarters around the corner rushed there arriving just in time to see a tall, gaunt figure smashing a small iron contraption with a sledge hammer. Absorbed in his studies and unaware of what was happening outside, Tesla had suddenly realized that the vibrations inside the building were getting out of control and that only the immediate destruction. of the oscillator would stop them.

During the Spanish-American War, when everyone was talking about America's great naval victory, Tesla staged a remarkable demonstration at Madison Square Garden. He equipped a model boat with radio equipment, placed it in a large tank built in the center of the arena, and started, steered and lighted the vessel by remote control. Tesla hoped that this invention would be used to make man's life easier not to end it. If there had to be wars, he wished to have them fought by robots instead of men. Neither the War Department nor commercial concerns, however, took any interest; again Tesla was too far ahead of his time.

His next important project (he worked on many problems simultaneously) was to build a high-powered broadcasting station that would permit the worldwide distribution of power by wireless. methods. Tesla thought (correctly) that the earth was electrically charged. At Colorado Springs he set up a plant that would add to the earth's charge so that electricity could be transported anywhere on the earth's surface without the use of conduits, poles or wires. It was an Olympian concept. Tesla considered these experiments a success, but unfortunately he left almost no written records about them; he carried everything in his head until he could complete the project but he never did.

To facilitate this wireless-power project and an equally staggering venture, the building of a world broadcasting station, in 1900 Tesla undertook to construct a radio city on Long Island. Many people thought he was crazy, but J. P. Morgan, who knew what Tesla had accomplished with AC, privately supported him with gifts which eventually totaled several hundred thousand dollars. This enabled Tesla to build a powerhouse and laboratory and to begin construction of a grotesque-looking broadcasting tower, some 150 feet high, capped with a giant copper hemisphere.

In 1905, however, Tesla went bankrupt and was forced to close his laboratory before he could complete the tower or begin broadcasting. He managed to pay all his creditors but made no attempt to collect the royalties that the manufacturers of the coils he had. invented now known as Tesla coils should have paid him.

The rest of his long life was an anticlimax. The millions he expected to make never materialized because he could not get the backing he needed to develop his grandiose, fantastic-sounding ideas. He continued to work on all kinds of inventions (one of the most important was a rotary turbine engine) but few of them were successful.

A well deserved honor seemed to be coming to him in 1912, when it was announced that he and Edison had been chosen to share the Nobel prize for physics. Despite his need for money, however, Tesla refused the award and the $20,000 that went with it. He felt that Edison was an "inventor" while himself was a "discoverer, and that to accept the prize would confuse the cateries. Then, too, he resented the fact that Marconi (whose work on radio Tesla had anticipated) had received the same honor three years before it was offered to him.

In 1917 Tesla was offered the Edison medal, given each year by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers for outstanding contributions to electrical art and science. Again he declined because he believed that the recognition had been too long delayed (30 years had passed, after all, since he had announced his AC system) and because he felt that the richly rewarded Edison would bask in reflected glory since the medal bore his name. Though Tesla was finally persuaded to accept the honor, he almost missed the presentation ceremony when he slipped away after the banquet to feed the pigeons around the New York Public Library.

During the 1920s the aging Tesla was almost forgotten. He was still inventing, but he found himself caught in a vicious cycle: He wanted to keep his discoveries secret until he had obtained patents, but he would not apply for patents until he had made actual working models, and he could not afford to make the models. Sometimes he was hard put to meet his personal expenses, and at one period he had to move from hotel to hotel because he was unable to pay his rent. But he remained optimistic and cheerful. He used to say that no one could understand how much satisfaction he received from knowing that the products of his brain had benefited man.

In the 1930s the startling announcement that Tesla had invented a death ray sent reporters scurrying to interview him. As early as the previous decade he had predicted (without foreseeing the atomic bomb) that in a few years it would be possible for nations to fight wars with weapons whose destructive action and range would have virtually no limit. Tesla implied, now, that he had. devised a combination wireless-power transmission and death ray which was beyond anyone's wildest dreams. He never revealed the principle on which his device was based, but the United States. Government (which had apparently ignored the military possibilities of Tesla's inventions) took no chances during World War II. A few hours after Tesla died, FBI agents came to his room, opened his safe and removed the papers it contained to see if they dealt. with any secret weapons. What was found has never been revealed.

In 1938 Tesla claimed that he had developed a method for interplanetary communication that would allow the transmission of huge amounts of energy. Perhaps that is why it was suggested not long ago, now that space travel has become a distinct possibility, that the first space station be named for him. Again, he left no record of his interstellar theories or experiments.

The last half-dozen years of his life were made easier by a 7200 yearly grant from the Yugoslav government, which had established in Belgrade the Tesla Institute, a research laboratory opened in 1936 in honor of Tesla's 80th birthday.

Still, he sometimes got behind with his hotel bills, often because of his generosity to those who did him even the slightest service or who appealed to him for help.

The softest side of his nature was reserved for the pigeons which he fed almost daily. Few people knew that the elderly man in the old-fashioned clothes, who scattered birdseed on the grounds of the New York Public Library or St. Patrick's Cathedral, was the once famous Tesla. If he was unable to make his usual rounds, he would hire a Western Union messenger boy to feed the birds. When the hotel management objected to the dirt brought by the flocks of pigeons, which had free entry to his room, he moved.

Not long before his death, which occurred on January 7, 1943, he confessed to an old friend that for one particular pigeon (al pure-white one with light-gray tips on its wings) he had felt the kind of love a man feels toward a woman. He had fed it and nursed it when it was sick, and when it died, he knew that his own work was finished. Thus Nikola Tesla had made the wisest discovery of his fabulous career that man, even a superman of science, cannot exist without love.