Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla Patent on Wireless Transmission of Electrical Signals

A patent issued April 18 to Mr. Nikola Tesla was briefly noticed in these columns last week, the subject being "The Art of Transmitting Electrical Energy Through the Natural Mediums." Below is given a fuller account of the patent.

In the preamble it is stated that experiments and observations have tended to confirm the opinion held by the majority of scientific men, that the earth, owing to its immense extent, does not behave in the manner of a conductor of limited dimensions with respect to electrical disturbances, but much like a vast reservoir or ocean, which, while it may be locally disturbed by commotion of some kind, remains unresponsive and quiescent in a large part or as a whole. The inventor states he has discovered that notwithstanding its vast dimensions and contrary to all observations heretofore made, the terrestrial globe may in a large part or as a whole behave toward disturbances impressed upon it in the same manner as a conductor of limited size.

In the course of certain investigations he noted unsuspected behavior of sensitive instruments, which he discovered to be due to the character of electrical waves produced in the earth by lightning discharges, and which had nodal regions following at definite distances the shifting source of the disturbances. From data obtained in a large number of observations on a maxima and minima of these waves, their length was found to vary approximately from 25 to 70 meters, and these results and certain theoretical deductions led to the conclusion that waves of this kind may be propagated in all directions over the globe, and that they may be of still more widely differing lengths, the extreme limit being imposed by the physical dimensions and properties of the earth. By means of gradual improvements in the generation of electrical oscillations, electrical movements were finally reached not only approximating, but, as shown in many comparative tests and measurements, actually surpassing those of lightning discharges; and by means of this apparatus it was found possible to reproduce whenever desired phenomena in the earth the same or similar to those due to such discharges.

For example, by the use of such a generator of stationary waves and receiving apparatus properly placed and adjusted in any other locality, however remote, it is practicable to transmit intelligible signals or to control or actuate at will any one or all of such apparatus for many other important and valuable purposes, as for indicating wherever desired the correct time of an observatory, or for ascertaining the relative position of a body or distance of the same with reference to a given point, or for determining the course of a moving object, such as a vessel at sea, the distance traversed by the same or its speed, or for producing many other useful effects at a distance dependent on the intensity, wave length; direction or velocity of movement, or other feature or property of disturbances of this character.

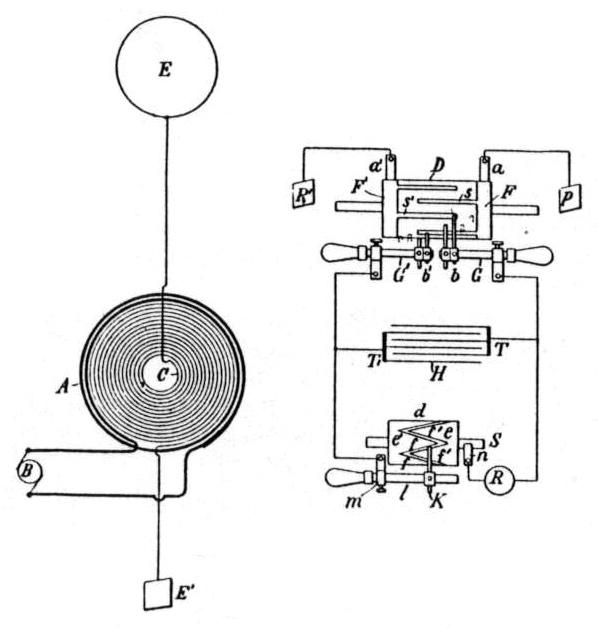

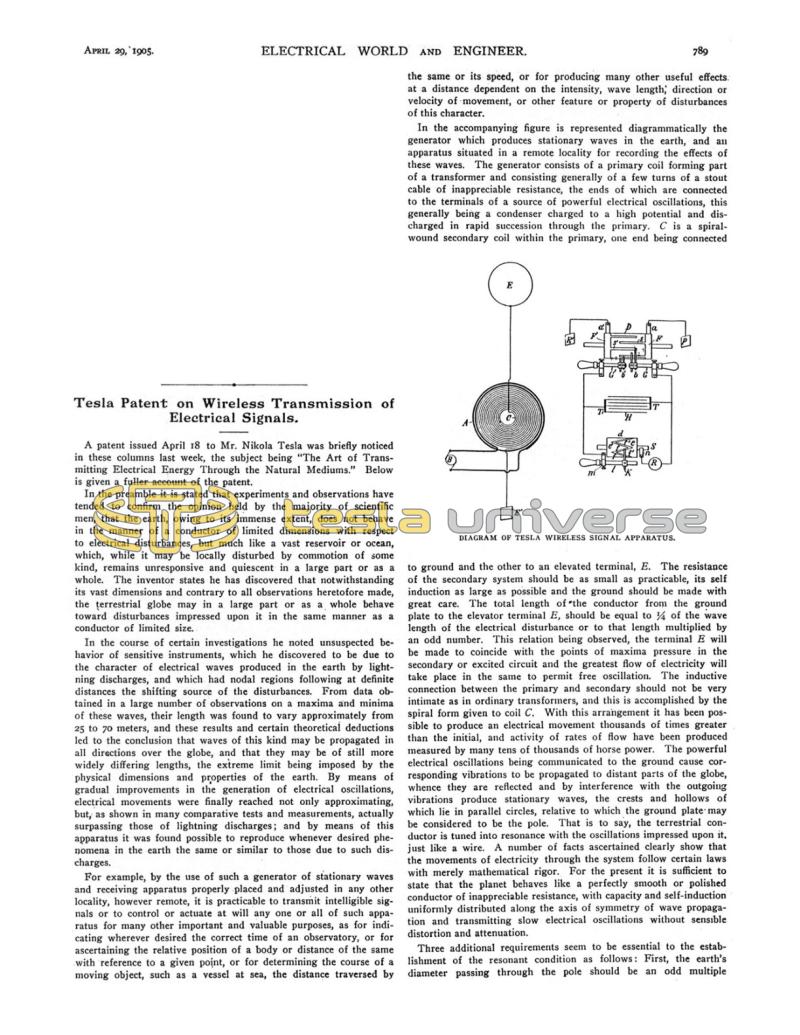

In the accompanying figure is represented diagrammatically the generator which produces stationary waves in the earth, and an apparatus situated in a remote locality for recording the effects of these waves. The generator consists of a primary coil forming part of a transformer and consisting generally of a few turns of a stout cable of inappreciable resistance, the ends of which are connected to the terminals of a source of powerful electrical oscillations, this generally being a condenser charged to a high potential and discharged in rapid succession through the primary. C is a spiral-wound secondary coil within the primary, one end being connected to ground and the other to an elevated terminal, E. The resistance of the secondary system should be as small as practicable, its self induction as large as possible and the ground should be made with great care. The total length of the conductor from the ground plate to the elevator terminal E, should be equal to 1/4 of the wave length of the electrical disturbance or to that length multiplied by an odd number. This relation being observed, the terminal E will be made to coincide with the points of maxima pressure in the secondary or excited circuit and the greatest flow of electricity will take place in the same to permit free oscillation. The inductive connection between the primary and secondary should not be very intimate as in ordinary transformers, and this is accomplished by the spiral form given to coil C. With this arrangement it has been possible to produce an electrical movement thousands of times greater than the initial, and activity of rates of flow have been produced measured by many tens of thousands of horse power. The powerful electrical oscillations being communicated to the ground cause corresponding vibrations to be propagated to distant parts of the globe, whence they are reflected and by interference with the outgoing vibrations produce stationary waves, the crests and hollows of which lie in parallel circles, relative to which the ground plate may be considered to be the pole. That is to say, the terrestrial conductor is tuned into resonance with the oscillations impressed upon it, just like a wire. A number of facts ascertained clearly show that the movements of electricity through the system follow certain laws with merely mathematical rigor. For the present it is sufficient to state that the planet behaves like a perfectly smooth or polished conductor of inappreciable resistance, with capacity and self-induction uniformly distributed along the axis of symmetry of wave propagation and transmitting slow electrical oscillations without sensible distortion and attenuation.

Three additional requirements seem to be essential to the establishment of the resonant condition as follows: First, the earth's diameter passing through the pole should be an odd multiple of the quarter wave length — that is, of the ratio between the velocity of light and four times the frequency of the currents; second, the frequency should be smaller than 20,000 per second. The lowest frequency would appear to be 6 per second, in which case there will be but one load at or near the ground plate, and, paradoxical as it may seem, the effect will increase with the distance and will be greatest in a region diametrically opposite the transmitter. With oscillations still slower, the earth, strictly speaking, will not resonate, but simply acts as a capacity, and the variations of potential will be more or less uniform over its entire surface; third, the main essential requirement is that, irrespective of frequency, the wave train will continue for a certain interval of time, which is estimated at not less than 1-12 or 0.08484 of a second, and which is taken in passing to and returning from the region diametrically opposite the pole over the earth's surface with a mean velocity of about 471,240 kilo meters per second.

Fig. 2 shows a device for detecting the presence of the waves. It consists of a cylinder D of insulating material, which is moved at a uniform rate of speed by clock-work or other suitable motor power, and is provided with two metal rings, F F' upon which bear brushes A A' connected to terminal plates. From the rings F F' extend narrow metallic segments S S', which by rotation of the cylinder D are brought alternately into contact with double brushes b b' carried by and in contact with conducting holders, H H', supported in the metal bearings, G G'. The latter are connected to the terminals T T' of a condenser H, and are capable of angular displacement as ordinary brush supports. The object of two brushes in the holder is to vary at will the duration of the electrical contact with the terminal plates and the condenser. To the latter is connected a receiver R and a device d performing the duty of closing the receiving circuit at predetermined intervals of time and charging the stored energy through the receiver.

The receiver consists of a cylinder made partly of conducting and partly of insulating material which is rotated at a desired rate of speed by any suitable means. The conducting part e is in electrical connection with the shaft S, upon which slides a brush K capable of longitudinal adjustment in the metallic support m. Another brush n is arranged to bear upon a shaft S. It will be seen that whenever one of the segments F' comes in contact with the brush K, the circuit including the receiver R is completed and the condenser discharged through the same. By suitable adjustment the circuit may be made to open and close in rapid succession and remain open or closed during such intervals of time as may be necessary.

The terminal plates P P', through which the electrical energy is conveyed to the brushes A A', may be at a considerable distance from each other in the ground or one in the ground and the other in the air, preferably at some height. In the latter case the location of the apparatus must be determined with reference to the position of the stationary waves. If both plates be connected to earth, the points of connection must be selected with reference to the differences of potential which it is desired to secure. In receiving, the speed of rotation of the cylinder D is varied until it is in synchronism with the alternate impulses of the distant generator; the brushes being properly adjusted electrical charges of the same sign will be conveyed to each of the terminals of the condenser and with each fresh impulse it will be charged to a higher potential. In this manner the energy of any number of separate impulses may be accumulated and discharged through the receiver R. Thus a relatively great amount of energy may be accumulated and the receiver need not be very sensitive. It being possible to shift the nodal and ventral regions of the waves at will from the sending station, the regions of maximum and minimum effect may be made to coincide with any receiving station or stations.

By impressing upon the earth two or more oscillations of different wave length, a resonant stationary wave may be made to travel slowly over the globe. If the nodal and ventral regions are maintained in a fixed position, the speed of a vessel carrying receiving apparatus may be exactly computed from observations of the maximum and minimum regions successively traversed. In any region at the surface the wave length can be ascertained from certain rules of geometry and conversely, knowing the wave length, the distance from the source can be readily calculated. Thus the distance of one point from another, the altitude and longitude, the hour, etc., may be obtained from the observation of such stationary waves. With several generators, preferably generating different wave lengths, installed in selected localities, the entire globe could be sub-divided in different zones of electrical activity and important data could be at once obtained by similar calculations or readings from suitably graduated instruments.