Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's Method of Transmitting Electrical Energy Through Space

Nikola Tesla of New York city, who, as is well known, has done much work of an original nature in the direction of the transmission of electrical energy through space, has recently been granted a patent (No. 787,412, April 18, 1905) upon such a method for the propagation of energy. The title of the patent is "Art of Transmitting Electrical Energy Through the Natural Mediums." Application for it was made May 16, 1900, and renewed June 17, 1902.

A fact now of common knowledge is that when electrical waves or oscillations are impressed upon such a conducting path as a metallic wire, reflection takes place, under certain conditions, from the ends of the wire, and in consequence of the interference of the impressed and reflected oscillations the phenomenon of "stationary waves" with maxima and minima in definite fixed positions is produced. The existence of these waves indicates that some of the outgoing waves have reached the boundaries of the conducting path and have been reflected therefrom. Mr. Tesla has been led to believe from his observations that notwithstanding its vast dimensions the terrestrial globe may in a large part or as a whole behave toward disturbances impressed upon it in the same manner as a conductor of limited size.

In the course of certain investigations which he carried on for the purpose of studying the effects of lightning discharges upon the electrical condition of the earth it was observed that sensitive receiving instruments arranged so as to be capable of responding to electrical disturbances created by the discharges at times failed to respond when they should have done so, and upon inquiring into the causes of this unexpected behavior it was discovered to be due to the character of the electrical waves which were produced in the earth by the lightning discharges and which had nodal regions following at definite distances the shifting source of the disturbances. From data obtained in a large number of observations of the maxima and minima of these waves their length has been found to vary approximately from 25 to 75 kilometers, and these results and certain theoretical deductions led Mr. Tesla to the conclusion that waves of this kind. may be propagated in all directions over the globe and that they may be of still more widely differing lengths, the extreme limits being imposed by the physical dimensions and properties of the earth.

Recognizing in the existence of these waves an unmistakable evidence that the disturbances created had been conducted from their origin to the most remote portions of the globe and had been thence reflected, the idea was conceived of producing such waves in the earth by artificial means with the object of utilizing them for many useful purposes for which they are or might be found applicable. This problem was rendered extremely difficult, owing to the immense dimensions of the planet, and consequently enormous movement of electricity or rate at which electrical energy had to be delivered in order to approximate, even in a remote degree, movements or rates which are manifestly attained in the displays of electrical forces in nature and which seemed at first unrealizable by any human agencies. But by gradual and continuous improvements of a generator of electrical oscillations, for which Mr. Tesla had previously obtained a patent, he finally succeeded in reaching electrical movements or rates of delivery of electrical energy which he believed not only approximated, but, as shown in many comparative tests and measurements, actually surpassed those of lightning discharges, and by means of this apparatus he found it possible to reproduce, whenever desired, phenomena in the earth the same as or similar to those due to such discharges.

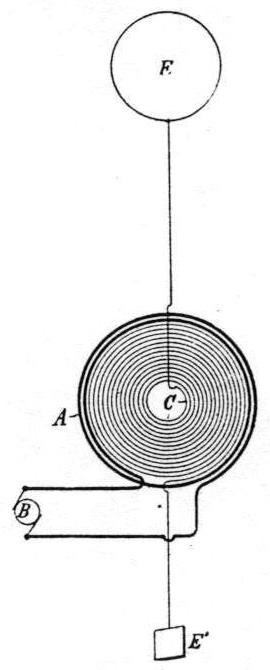

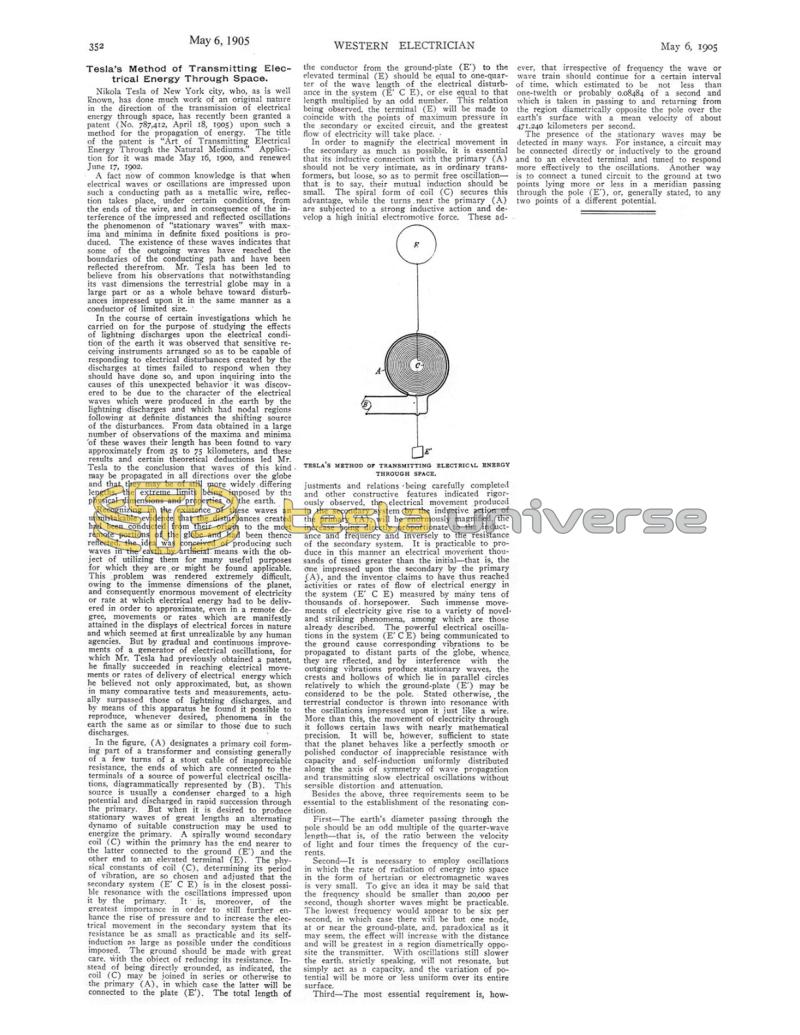

In the figure, (A) designates a primary coil forming part of a transformer and consisting generally of a few turns of a stout cable of inappreciable resistance, the ends of which are connected to the terminals of a source of powerful electrical oscillations, diagrammatically represented by (B). This source is usually a condenser charged to a high potential and discharged in rapid succession through the primary. But when it is desired to produce stationary waves of great lengths an alternating dynamo of suitable construction may be used to energize the primary. A spirally wound secondary coil (C) within the primary has the end nearer to the latter connected to the ground (E') and the other end to an elevated terminal (E). The physical constants of coil (C), determining its period of vibration, are so chosen and adjusted that the secondary system (E' C E) is in the closest possible resonance with the oscillations impressed upon it by the primary. It is, moreover, of the greatest importance in order to still further enhance the rise of pressure and to increase the electrical movement in the secondary system that its resistance be as small as practicable and its selfinduction as large as possible under the conditions imposed. The ground should be made with great care, with the object of reducing its resistance. Instead of being directly grounded, as indicated, the coil (C) may be joined in series or otherwise to the primary (A), in which case the latter will be connected to the plate (E'). The total length of the conductor from the ground-plate (E') to the elevated terminal (E) should be equal to one-quarter of the wave length of the electrical disturbance in the system (E' C E), or else equal to that length multiplied by an odd number. This relation being observed, the terminal (E) will be made to coincide with the points of maximum pressure in the secondary or excited circuit, and the greatest flow of electricity will take place.

In order to magnify the electrical movement in the secondary as much as possible, it is essential that its inductive connection with the primary (A) should not be very intimate, as in ordinary transformers, but loose, so as to permit free oscillation — that is to say, their mutual induction should be small. The spiral form of coil (C) secures this advantage, while the turns near the primary (A) are subjected to a strong inductive action and develop a high initial electromotive force. These adjustments and relations being carefully completed and other constructive features indicated rigorously observed, the electrical movement produced in the secondary system by the inductive action of the primary (A), will be enormously magnified, the increase being directly proportionate to the inductance and frequency and inversely to the resistance of the secondary system. It is practicable to produce in this manner an electrical movement thousands of times greater than the initial — that is, the one impressed upon the secondary by the primary (A), and the inventor claims to have thus reached activities or rates of flow of electrical energy in the system (E' C E) measured by many tens of thousands of horsepower. Such immense movements of electricity give rise to a variety of novel and striking phenomena, among which are those already described. The powerful electrical oscillations in the system (E' C E) being communicated to the ground cause corresponding vibrations to be propagated to distant parts of the globe, whence, they are reflected, and by interference with the outgoing vibrations produce stationary waves, the crests and hollows of which lie in parallel circles relatively to which the ground-plate (E') may be considered to be the pole. Stated otherwise, the terrestrial conductor is thrown into resonance with the oscillations impressed upon it just like a wire. More than this, the movement of electricity through it follows certain laws with nearly mathematical precision. It will be, however, sufficient to state that the planet behaves like a perfectly smooth or polished conductor of inappreciable resistance with capacity and self-induction uniformly distributed along the axis of symmetry of wave propagation and transmitting slow electrical oscillations without sensible distortion and attenuation.

Besides the above, three requirements seem to be essential to the establishment of the resonating condition.

First — The earth's diameter passing through the pole should be an odd multiple of the quarter-wave length — that is, of the ratio between the velocity of light and four times the frequency of the currents.

Second — It is necessary to employ oscillations in which the rate of radiation of energy into space in the form of hertzian or electromagnetic waves is very small. To give an idea it may be said that the frequency should be smaller than 20,000 per second, though shorter waves might be practicable. The lowest frequency would appear to be six per second, in which case there will be but one node, at or near the ground-plate, and, paradoxical as it may seem, the effect will increase with the distance and will be greatest in a region diametrically opposite the transmitter. With oscillations still slower the earth, strictly speaking, will not resonate, but simply act as a capacity, and the variation of potential will be more or less uniform over its entire surface.

Third — The most essential requirement is, however, that irrespective of frequency the wave or wave train should continue for a certain interval of time, which estimated to be not less than one-twelfth or probably 0.08484 of a second and which is taken in passing to and returning from the region diametrically opposite the pole over the earth's surface with a mean velocity of about 471,240 kilometers per second.

The presence of the stationary waves may be detected in many ways. For instance, a circuit may be connected directly or inductively to the ground and to an elevated terminal and tuned to respond more effectively to the oscillations. Another way is to connect a tuned circuit to the ground at two points lying more or less in a meridian passing through the pole (E'), or, generally stated, to any two points of a different potential.