Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's New Method of and Apparatus for Fluid Propulsion

Invention of a Turbine and Pump

In an address before the New York section of the National Electric Light Association on May 15 of this year, Nikola Tesla devoted a few remarks to a new mechanical principle he had developed, and exhibited diagrams and working drawings in explanation of the same. He also alluded to the fact that several of his machines were to be seen in operation at the Waterside Station of the New York Edison Company, which had courteously extended to Dr. Tesla its facilities. The Electrical Review and Western Electrician of May 20 published an exclusive and full report of Dr. Telsa's address.

We present herewith the first authoritative description in the inventor's own words, which, on account of the great importance of the subject, cannot fail to excite interest in engineering circles the world over.

In the practical application of mechanical power based on the use of a fluid as vehicle of energy it has been demonstrated that, in order to attain the highest economy, the changes in velocity and direction of movement of the fluid should be as gradual as possible. In the present forms of such apparatus more or less sudden changes, shocks and vibrations are unavoidable. Besides, the employment of the usual devices for imparting to, or deriving energy from a fluid, as pistons, paddles, vanes and blades, necessarily introduces numerous defects and limitations and adds to the complication, cost of production and maintenance of the machine.

The purpose of the invention is to overcome these deficiencies and to effect the transmission and transformation of mechanical energy through the agency of fluids in a more perfect manner, and by means simpler and more economical than those heretofore employed.

This is accomplished by causing the propelled or propelling fluid to move in natural paths or stream lines of least resistance, free from constraint and disturbance such as occasioned by vanes or kindred devices, and to change its velocity and direction of movement by imperceptible degrees, thus avoiding the losses due to sudden variations while the fluid is receiving or imparting energy.

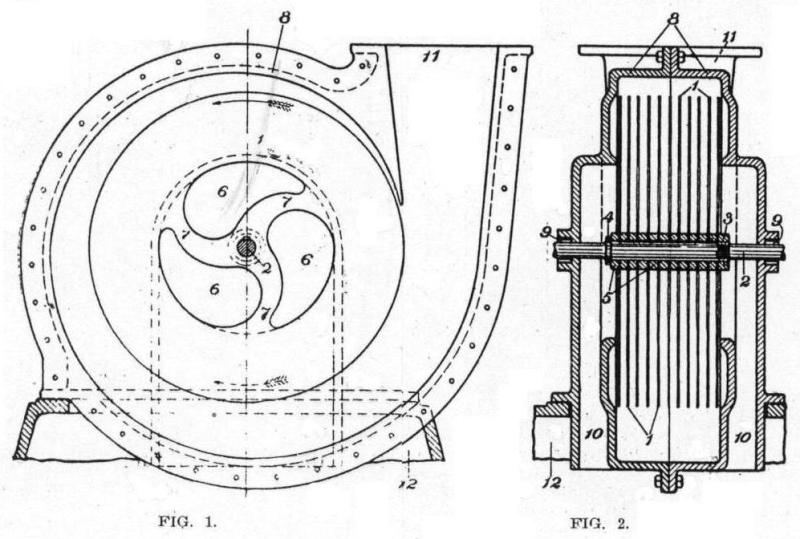

It is well known that a fluid possesses, among others, two salient properties; adhesion and viscosity. Owing to these a body propelled through such a medium encounters a peculiar impediment known as "lateral," or "skin resistance," which is twofold: one arising from the shock of the fluid against the asperities of the solid substance, the other from internal forces opposing molecular separation. As an inevitable consequence a certain amount of the fluid is dragged along by the moving body. Conversely, if the body be placed in a fluid in motion, for the same reasons, it is impelled in the direction of movement. The accompanying drawings illustrate operative and efficient embodiments of the idea.

Fig. 1 is a partial end view, and Fig. 2 a vertical cross-section of a pump or compressor, while Figs. 3 and 4 represent, respectively, in corresponding views, a rotary engine or turbine, both machines being constructed and adapted to be operated in accordance with the invention.

Figs. 1 and 2 show a runner composed of a plurality of flat rigid disks 1 of a suitable diameter, keyed to a shaft 2 and held in position by a threaded nut 3, a shoulder 4 and washers 5 of the requisite thickness. Each disk has a number of central openings 6, the solid portions between which form spokes 7 preferably curved, as shown, for the purpose of reducing the loss of energy due to the impact of the fluid.

This runner is mounted in a two-part volute casing 8 having stuffing boxes 9 and inlets 10 leading to its central portion. In addition a gradually widening and rounding outlet 11 is provided formed with a flange for connection to a pipe as usual. The casing 8 rests upon a base 12 shown only in part and supporting the bearings for the shaft 2, which, being of ordinary construction, are omitted from the drawings.

An understanding of the principle embodied in this apparatus will be gained from the following description of its mode of operation.

Power being applied to the shaft and the runner set in rotation in the direction of the solid arrow, the fluid, by reason of its properties of adherence and viscosity, upon entering through the inlets 10 and coming in contact with the disks 1 is taken hold of by the same and subjected to two forces, one acting tangentially in the direction of rotation, and the other radially outward. The combined effect of these tangential and centrifugal forces is to propel the fluid with continuously increasing velocity in a spiral path until it reaches the outlet 11 from which it is ejected. This spiral movement, free and undisturbed and essentially dependent on these properties of the fluid, permitting it to adjust itself to natural paths or stream lines and to change its velocity and direction by insensible degrees, is characteristic of this method of propulsion and advantageous in its application.

While traversing the chamber inclosing the runner, the particles of the fluid may complete one or more turns, or but a part of one turn. In any given case their path can be closely calculated and graphically represented, but fairly accurate estimates of turns can be obtained simply by determining the number of revolutions required to renew the fluid passing through the chamber and multiplying it by the ratio between the mean speed of the fluid and that of the disks.

It has been found that the quantity of fluid propelled in this manner is, other conditions being equal, approximately proportionate to the active surface of the runner and to its effective speed. For this reason, the performance of such machines augments at an exceedingly high rate with the increase of their size and speed of revolution.

The dimensions of the apparatus as a whole, and the spacing of the disks in any given machine, will be determined by the conditions and requirements of special cases. It may be stated that the intervening distance should be the greater, the larger the diameter of the disks, the longer the spiral path of the fluid and the greater its viscosity. In general, the spacing should be such that the entire mass of the fluid, before leaving the runner, is accelerated to a nearly uniform velocity, not much below that of the periphery of the disks under normal working conditions and almost equal to it when the outlet is closed and the particles move in concentric circles.

It may also be pointed out that such a pump can be made without openings and spokes in the runner, as by using one or more solid disks, each in its own casing, in which form the machine will be eminently adapted for sewage, dredging and the like, when the water is charged with foreign bodies and spokes or vanes are especially objectionable.

Another application of this principle, thoroughly practicable and efficient, is the utilization of machines such as described for the compression or rarefaction of air, or gases in general. In such cases most of the general considerations obtaining in the case of liquids, properly interpreted, hold true.

When, irrespective of the character of the fluid, considerable pressures are desired, staging or compounding may be resorted to in the usual way, the individual runners being, preferably, mounted on the same shaft. It should be added that the same end may be attained with one single runner by suitable deflection of the fluid through rotative or stationary passages.

The principles underlying the invention are capable of embodiment also in that field of mechanical engineering which is concerned in the use of fluids as motive agents, for while in some respects the actions in the latter case are directly opposite to those met with in the propulsion of fluids, the fundamental laws applicable in the two cases are the same. In other words, the operation above described is reversible, for if water or air under pressure be admitted to the opening 11 the runner is set in rotation in the direction of the dotted arrow by reason of the peculiar properties of the fluid which, traveling in a spiral path and with continuously diminishing velocity, reaches the orifices 6 and 10 through which it is discharged. If the runner be allowed to turn freely, in nearly frictionless bearings, its rim will attain a speed closely approximating the maximum of that of the fluid in the volute channel and the spiral path of the particles will be comparatively long, consisting of many almost circular turns. If the load is put on and the runner slowed down, the motion of the fluid is retarded, the turns are reduced, and the path is shortened.

Owing to a number of causes affecting the performance, it is difficult to frame a precise rule which would be generally applicable, but it may be stated that within certain limits, and other conditions being the same, the torque is directly proportional to the square of the velocity of the fluid relatively to the runner and to the effective area of the disks and, inversely, to the distance separating them. The machine will, generally, perform its maximum work when the effective speed of the runner is one-half of that of the fluid. But to attain the highest economy the relative speed or slip, for any given performance, should be as small as possible. This condition may be to any desired degree approximated by increasing the active area and reducing the space between the disks.

When apparatus of the kind described is employed for the transmission of power, certain departures from similarity between transmitter and receiver may be necessary for securing the best result. It is evident that, when transmitting power from one shaft to another by such machines, any desired ratio between the speeds of rotation may be obtained by proper selection of the diameters of the disks, or by suitably staging the transmitter, the receiver, or both. But it may be pointed out that in one respect, at least, the two machines are essentially different. In the pump, the radial or static pressure, due to centrifugal force, is added to the tangential or dynamic, thus increasing the effective head and assisting in the expulsion of the fluid. In the motor, on the contrary, the first named pressure, being opposed to that of supply, reduces the effective head and the velocity of radial flow towards the center. Again, in the propelled machine a great torque is always desirable, this calling for an increased number of disks and smaller distance of separation, while in the propelling machine, for numerous economic reasons, the rotary effort should be the smallest and the speed the greatest practicable. Many other considerations, which will naturally suggest themselves, may affect the design and construction, but the preceding is thought to contain all necessary information in this regard.

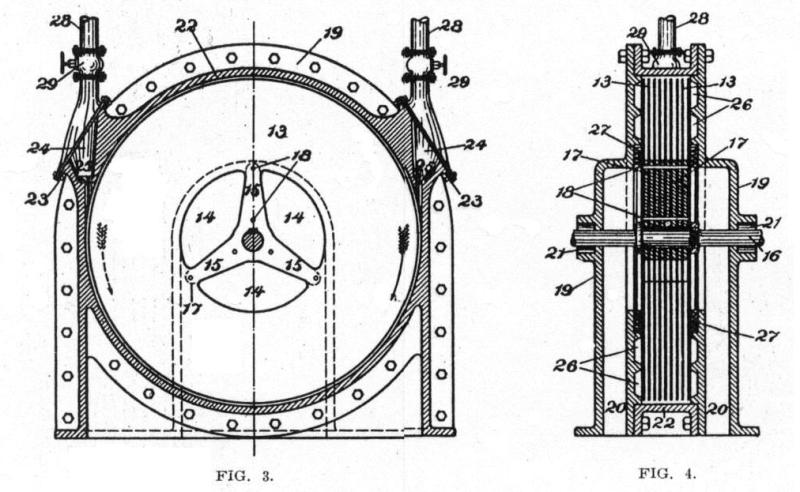

The greatest value of this invention will be found in its use for the thermodynamic conversion of energy. Reference is now made to Figs. 3 and 4, illustrative Of the manner in which it is, or may be, so applied.

As in the previous figures, a runner is provided made up of disks 13 with openings 14 and spokes 15 which, in this case, may be straight. The disks are keyed to and held in position on a shaft 16, mounted to turn freely in suitable bearings, not shown, and are separated by washers 17 conforming in shape with the spokes and firmly united thereto by rivets 18. For the sake of clearness but a few disks, with comparatively wide intervening spaces, are indicated.

The runner is mounted in a casing comprising two end-castings 19 with outlets 20 and stuffing boxes 21, and a central ring 22, which is bored out to a circle of a diameter slightly larger than that of the disks, and has flanged extensions 23 and inlets 24 into which finished ports, or nozzles 25 are inserted. Circular grooves 26 and labyrinth packings 27 are provided on the sides of the runner. Supply pipes 28, with valves 29, are connected to the flanged extensions of the central ring, one of the valves being normally closed.

With the exception of certain particulars, which will be elucidated, the mode of operation will be understood from the preceding description. Steam or gas under pressure being allowed to pass through the valve at the side of the solid arrow, the runner is set in rotation in clockwise direction.

In order to bring out a distinctive feature assume, in the first place, that the motive medium is admitted to the disk chamber through a port, that is, a channel which it traverses with nearly uniform velocity. In this case, the machine will operate as a rotary engine, the fluid continuously expanding on its tortuous path to the central outlet. The expansion takes place chiefly along the spiral path, for the spread inward is opposed by the centrifugal force due to the velocity of whirl and by the great resistance to radial exhaust. It is to be observed that the resistance to the passage of the fluid between the plates is approximately proportional to the square of the relative speed, which is maximum in the direction towards the center and equal to the full tangential velocity of the fluid. The path of least resistance, necessarily taken in obedience to a universal law of motion, is virtually, also that of least relative velocity.

Next, assume that the fluid is admitted to the disk chamber not through a port, but a diverging nozzle, a device converting, wholly or in part, the expansive energy into velocity-energy. The machine will then work rather like a turbine, absorbing the energy of kinetic momentum of the particles as they whirl, with continuously decreasing speed, to the exhaust.

The above description of the operation is suggested by experience and observation and is advanced merely for the purpose of explanation. The undeniable fact is that the machine does operate, both expansively and impulsively. When the expansion in the nozzle is complete, or nearly so, the fluid pressure in the peripheral clearance space is small; as the nozzle is made less divergent and its section enlarged, the pressure rises, finally approximating that of the supply. But the transition from purely impulsive to expansive action may not be continuous throughout, on account of critical states and conditions, and comparatively great variations of pressure may be caused by small changes of nozzle velocity.

In the preceding it has been assumed that the pressure of supply is constant or continuous, but it will be understood that the operation will be, essentially, the same if the pressure be fluctuating or intermittent, as that due to explosions occurring in more or less rapid succession.

A very desirable feature, characteristic of machines constructed and operated in accordance with this invention, is their capability of reversal of rotation. Fig. 3, while illustrative of a special case, may be regarded as typical in this respect. If the right hand valve be shut off and the fluid supplied through the second pipe, the runner is rotated in the direction of the dotted arrow, the operation, and also the performance, remaining the same as before, the central ring being bored to a circle with this purpose in view. The same result may be obtained in many other ways by specially designed valves, ports or nozzles for reversing the flow, the description of which is omitted here in the interest of simplicity and clearness. For the same reasons but one operative port or nozzle is illustrated, which might be adapted to a volute but does not fit best a circular bore. It is evident that a number of suitable inlets may be provided around the periphery of the runner to improve the action and that the construction of the machine may be modified in many ways.

Still another valuable and probably unique quality of such motors or prime movers may be described. By proper construction and observance of working conditions the centrifugal pressure, opposing the passage of the fluid, may, as already indicated, be made nearly equal to the pressure of supply when the machine is running idle. If the inlet section be large, small changes in the speed of revolution will produce great differences of flow which are further enhanced by the concomitant variations in the length of the spiral path. A self-regulating machine is thus obtained hearing a striking resemblance to a direct-current electric motor in this respect, that, with great differences of impressed pressure in a wide open channel, the flow of the fluid through the same is prevented by virtue of rotation. Since the centrifugal head increases as the square of the revolutions, or even more rapidly, and with modern high-grade steel great peripheral velocities are practicable, it is possible to attain that condition in a single-stage machine, more readily if the runner be of large diameter. Obviously this problem is facilitated by compounding. Now irrespective of its bearing on economy, this tendency which is, to a degree, common to motors of the above description, is of special advantage in the operation of large units, as it affords a safeguard against running away and destruction.

Besides these, such a prime mover possesses other advantages, both constructive and operative. It is simple, light and compact, subject to but little wear, cheap and exceptionally easy to manufacture as small clearances and accurate milling work are not essential to good performance. In operation it is reliable, there being no valves, sliding contacts or troublesome vanes. It is almost free of windage, largely independent of nozzle efficiency and suitable for high as well as for low fluid velocities and speeds of revolution. The principles of construction and operation are capable of embodiment in machines of the most widely different forms, and adapted for the greatest variety of purposes.