Nikola Tesla Articles

Theory of the Tesla Turbine

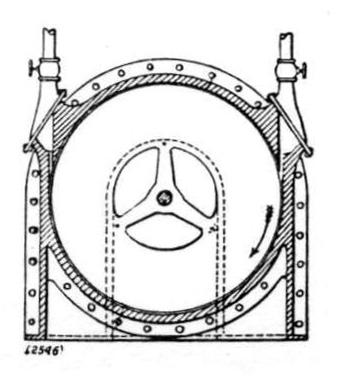

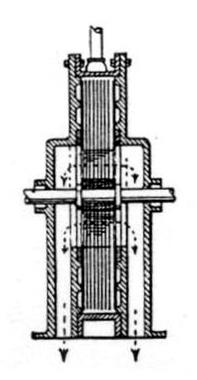

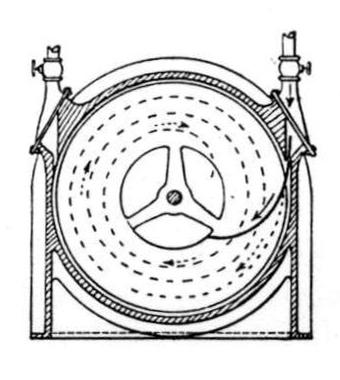

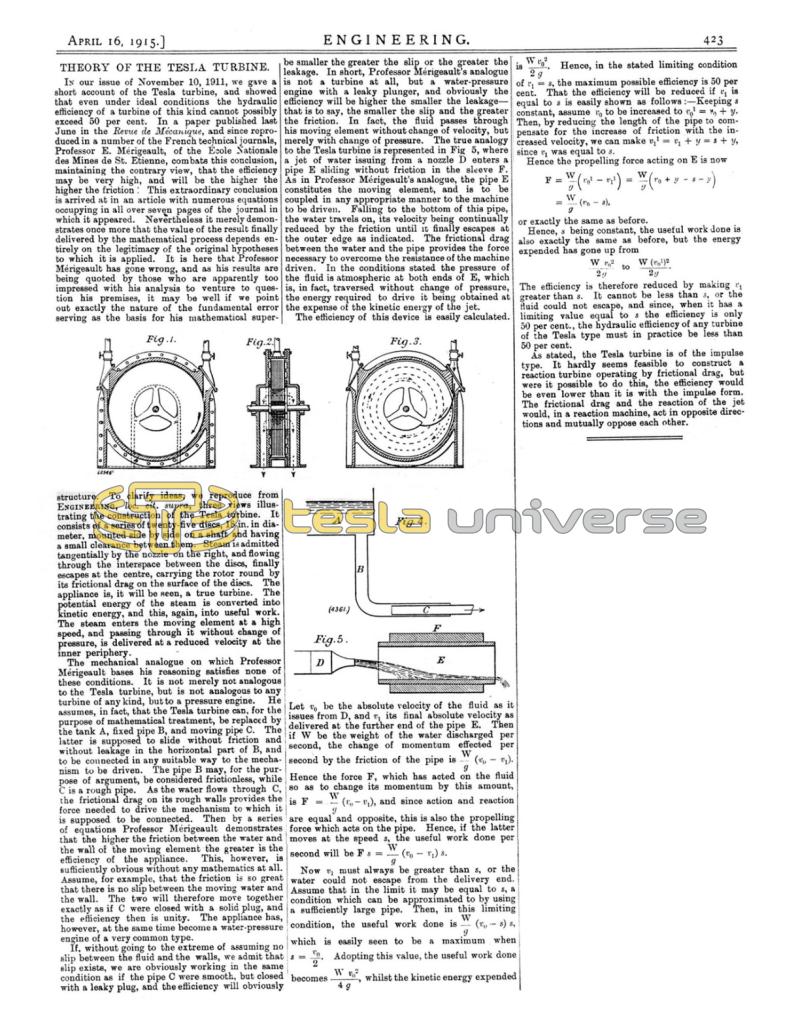

In our issue of November 10, 1911, we gave a short account of the Tesla turbine, and showed that even under ideal conditions the hydraulic efficiency of a turbine of this kind cannot possibly exceed 50 per cent. In a paper published last June in the Revue de Mécanique, and since reproduced in a number of the French technical journals, Professor E. Mérigeault, of the Ecole Nationale des Mines de St. Etienne, combats this conclusion, maintaining the contrary view, that the efficiency may be very high, and will be the higher the higher the friction: This extraordinary conclusion is arrived at in an article with numerous equations occupying in all over seven pages of the journal in which it appeared. Nevertheless it merely demonstrates once more that the value of the result finally delivered by the mathematical process depends entirely on the legitimacy of the original hypotheses to which it is applied. It is here that Professor Mérigeault has gone wrong, and as his results are being quoted by those who are apparently too impressed with his analysis to venture to question his premises, it may be well if we point out exactly the nature of the fundamental error serving as the basis for his mathematical super-structure. To clarify ideas, we reproduce from Engineering, loc. cit. supra, three views illustrating the construction of the Tesla turbine. It consists of a series of twenty-five discs, 18 in. in diameter, mounted side by side on a shaft and having a small clearance between them. Steam is admitted tangentially by the nozzle on the right, and flowing through the interspace between the discs, finally escapes at the centre, carrying the rotor round by its frictional drag on the surface of the discs. The appliance is, it will be seen, a true turbine. The potential energy of the steam is converted into kinetic energy, and this, again, into useful work. The steam enters the moving element at a high speed, and passing through it without change of pressure, is delivered at a reduced velocity at the inner periphery.

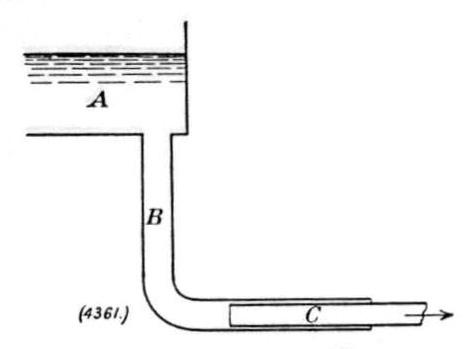

The mechanical analogue on which Professor Mérigeault bases his reasoning satisfies none of these conditions. It is not merely not analogous to the Tesla turbine, but is not analogous to any turbine of any kind, but to a pressure engine. He assumes, in fact, that the Tesla turbine can, for the purpose of mathematical treatment, be replaced by the tank A, fixed pipe B, and moving pipe C. The latter is supposed to slide without friction and without leakage in the horizontal part of B, and to be connected in any suitable way to the mechanism to be driven. The pipe B may, for the purpose of argument, be considered frictionless, while C is a rough pipe. As the water flows through C, the frictional drag on its rough walls provides the force needed to drive the mechanism to which it is supposed to be connected. Then by a series of equations Professor Mérigeault demonstrates that the higher the friction between the water and the wall of the moving element the greater is the efficiency of the appliance. This, however, is sufficiently obvious without any mathematics at all. Assume, for example, that the friction is so great that there is no slip between the moving water and the wall. The two will therefore move together exactly as if C were closed with a solid plug, and the efficiency then is unity. The appliance has, however, at the same time become a water-pressure engine of a very common type.

If, without going to the extreme of assuming no slip between the fluid and the walls, we admit that slip exists, we are obviously working in the same condition as if the pipe C were smooth, but closed with a leaky plug, and the efficiency will obviously be smaller the greater the slip or the greater the leakage. In short, Professor Mérigeault's analogue is not a turbine at all, but a water-pressure engine with a leaky plunger, and obviously the efficiency will be higher the smaller the leakage — that is to say, the smaller the slip and the greater the friction. In fact, the fluid passes through his moving element without change of velocity, but merely with change of pressure. The true analogy to the Tesla turbine is represented in Fig 5, where a jet of water issuing from a nozzle D enters a pipe E sliding without friction in the sleeve F. As in Professor Mérigeault's analogue, the pipe E constitutes the moving element, and is to be coupled in any appropriate manner to the machine to be driven. Falling to the bottom of this pipe, the water travels on, its velocity being continually reduced by the friction until it finally escapes at the outer edge as indicated. The frictional drag between the water and the pipe provides the force necessary to overcome the resistance of the machine driven. In the conditions stated the pressure of the fluid is atmospheric at both ends of E, which is, in fact, traversed without change of pressure, the energy required to drive it being obtained at the expense of the kinetic energy of the jet.

The efficiency of this device is easily calculated. Let !$v_0!$ be the absolute velocity of the fluid as it issues from D, and !$v_1!$ its final absolute velocity as delivered at the further end of the pipe E. Then if W be the weight of the water discharged per second, the change of momentum effected per second by the friction of the pipe is !$\frac{W}{g}(v_0 - v_1)!$. Hence the force F, which has acted on the fluid so as to change its momentum by this amount, is !$F = \frac{W}{g}(v_0 - v_1)!$, and since action and reaction are equal and opposite, this is also the propelling force which acts on the pipe. Hence, if the latter moves at the speed !$s!$, the useful work done per second will be !$Fs = \frac{W}{g}(v_0 - v_1) s!$.

Now !$v_1!$ must always be greater than !$s!$, or the water could not escape from the delivery end. Assume that in the limit it may be equal to !$s!$, a condition which can be approximated to by using a sufficiently large pipe. Then, in this limiting condition, the useful work done is !$\frac{W}{g}(v_0 - s) s!$, which is easily seen to be a maximum when !$ s = \frac{v_0}{2}!$. Adopting this value, the useful work done becomes !$\frac{W v_0{2}}{4 g}!$, whilst the kinetic energy expended Vo 3= 2 becomes is !$\frac{W v_0{2}}{2 g}!$. Hence, in the stated limiting condition !$v_1 = s!$, the maximum possible efficiency is 50 per cent. That the efficiency will be reduced if !$ v_1 !$ is equal to !$s!$ is easily shown as follows: — Keeping !$s!$ constant, assume !$ v_0 !$ to be increased to !$ v_0{1} = v_0 + y !$. Then, by reducing the length of the pipe to com- pensate for the increase of friction with the in- creased velocity, we can make !$ v_1{1} = v_1 + y = s + y !$, since !$ v_1 !$ was equal to !$s!$.

Hence the propelling force acting on E is now $$F = \frac{W}{g} (r_0^1 - r_1^1) = \frac{W}{g} (r_0 + y - s - y) = \frac{W}{g} (r_0 - s)$$, or exactly the same as before.

Hence, !$s!$ being constant, the useful work done is also exactly the same as before, but the energy expended has gone up from !$\frac{W r_0{2}}{2g}!$ to !$\frac{W (r_0^1)^2}{2g}.!$. The efficiency is therefore reduced by making !$ v_1 !$ greater than !$s!$. It cannot be less than !$s!$, or the fluid could not escape, and since, when it has a limiting value equal to !$s!$ the efficiency is only 50 per cent., the hydraulic efficiency of any turbine of the Tesla type must in practice be less than 50 per cent.

As stated, the Tesla turbine is of the impulse type. It hardly seems feasible to construct a reaction turbine operating by frictional drag, but were it possible to do this, the efficiency would be even lower than it is with the impulse form. The frictional drag and the reaction of the jet would, in a reaction machine, act in opposite directions and mutually oppose each other.