Nikola Tesla Articles

The Thought Recorder

When the writer first conceived the idea of the thought recorder, he asked three prominent scientists regarding their views on recording thoughts electrically. The letters are reproduced herewith excerpted. It will be noted that Nikola Tesla disagrees with the writer as to thought transmission at all, but his letter nevertheless will give considerable food for thought to many readers.

Dr. Lee de Forest, inventor of the audion, is not too sure about thought transmission.

Dr. Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, the inventor of the silicon and pericon detector, as well as many other wireless specialties, has several interesting ideas, and his letter will certainly prove a revelation, particularly to those interested in radio.

In studying the evolution of the human specie we must go back to the time when man proper, as we know him, had not as yet arrived on this planet. Our great biologists have irrefutable evidence that everything in Nature works on a slow, laborious plan, one specie being developed slowly into another from the smallest animalculae up to present man. When man was still in the what we may call animal stage, i.e., when he was not "thinking," as that term is understood, he was wholly guided by instinct. His "thoughts," if so they may be called, were probably on a much lower plane than thoughts of the average dog. The chances are that the present day dog probably "thinks" much better than prehistoric man. We also find that thought and language go hand in hand. Crudely speaking, prehistoric man had no better language than any highly developed animal, such as a dog, cat or a horse.

Thru thousands of years of evolution, however, instinct developed into crude thought, and finally there came a time when prehistoric man really began to think, as we know the term. That was the time when he began to utter his thoughts by means of his voice. At first only a few crude words were formulated, and probably consisted of not much more than the gibberish of a chimpanzee. Little by little organized thought arrived, and words, translated into speech kept pace with the advancing thought of man. As the human race kept advancing at a slow pace, its thinking qualities increased little by little, and the senses correspondingly became more sharpened.

THREE FAMOUS SCIENTISTS' VIEWS ON THOUGHT TRANSMISSION

Altho I am clinging to ideals, my conception of the universe is, I fear, grossly materialistic. As stated in some of my published articles, I have satisfied myself thoroly thru careful observation carried on for many years that we are simply automata eting in obedience to external influences, without power or initiative, The brain is not an accumulator as commonly held in philosophy, and contains no records whatever of a phonographic or photographic kind. In other words, there is no stored knowledge or memory as usually conceived, our minds are blanks. The brain has merely the quality to respond, becoming more and more sus ceptible as the impressions are often repeated, this resulting in memory.

There is a possibility, however, which I have indicated years ago, that we may finally succeed in not only reading thoughts accurately, but reproducing faithfully every mental image. It can be done thru the analysis of the retina, which is instrumental in conveying impressions to the nerve centers and, in my opinion, is also capable of serving as an indicator of the mental processes taking place within. Evidently, when an object is seen, consciousness of the external form can only be due to the fact that those cones and rods of the retina which are covered by the image are affected differently from the rest, and it is a speculation not too hazardous to assume that visualization is accompanied by a reflex action on the retina which might be detected by suitable instruments. In this way it might also be possible to project the reflex image on a screen, and with further refinement, resorting to the principle involved in moving pictures, the continuous play of thoughts might be rendered visible, recorded and at will reproduced.

Nikola Tesla.

Your article should be an interesting one, particularly as to the audion suggestion. The audion, however, seems to have a certain wavelength limitation, so that unless the waves to be recorded lie between about 3 X 1010 cm. and 3 X 102 cm., they are not apt to be "picked up."

A more likely range to search would be from 3 X 102 cm. down to 3 X 1010 cm., that is, down to the harder Gamma rays, or to even shorter wavelengths, starting with the shorter Hertzian waves. Here the audion would be useless, save as a second stage in the detection, i.e., as an amplifier for some other form of detector.

Greenleaf W. Pickard.

While I have little doubt that there is such a thing in nature as transference of thought from one brain to another, I am not aware that sufficient data has ever been gathered on such a highly abstruse subject to permit forming any definite opinion.

Lee De Forest.

This is especially true of the human thinking machinery which perhaps has advanced more rapidly than the senses. Thus we find that certain senses have even been retarded, such as, for instance, sight, smell and hearing. When man lived his wild life it was very necessary for these senses to be much sharper than they are at present; hence our poor hearing, bad sight and very much poorer smell. On the other hand, as the battle for existence becomes more and more acute, and as moreover the battle is not as much physical as mental, it follows that the mind and its thinking machinery should naturally become more and more developed, which, in fact, it does. We may safely say that within the next hundred thousand years — which is only a small span of time in man's evolution — the human mind will be an entirely different sort of apparatus than it is today. Man's mental power will be infinitely greater than what it is at present. Already we have indications that man's thoughts, or the effects therefrom, do not necessarily have to remain within his skull, but that they actually radiate from the latter in a very imperfect manner. As the human race advances, there is no doubt that thought transference proper will become an accomplished fact. It has already been shown experimentally by Di Brazza, as well as Charpentier, that concentrated thinking will produce certain external effects, as for instance, a slight fluorescence on a zinc sulfid screen, or a suitably excited X-ray screen. This would tend to prove that thoughts are of an electrical nature, having probably a very short wave length. As most electrical effects in space are depend- (Continued on page 84) ent upon wave motion, it should not be sur- prising therefore that thoughts or active thinking should give rise to wave motion as well.

This theory is greatly strengthened by the fact that it has been proven beyond doubt that active thinking necessitates an expenditure of energy. If you sit perfectly quiet in a chair without expending any visible muscular energy, and if you concentrate very hard upon a certain problem, it is not infrequent that perspiration appears on your forehead from the simple effort of thinking. Of course, this is rather a complex phenomenon, as the perspiration is not produced directly, but rather indirectly by the nerve centers working upon the human organs, principally the heart. Nevertheless, we know that thinking proper calls for an expenditure of energy in the brain itself. That this energy is considerable can also be shown experimentally.

It therefore cannot come as a surprise that the act of thinking should give rise to a direct wave motion, sending out from the brain certain waves in an analogous manner, to the spoken word which produces sound waves of a certain wave length. It is quite probable, however, that thought waves are simply another form of ether waves, the same as radio waves or light waves. Just as "ght rays traverse thru a thick glass pane without suffering any appreciable loss, just so will thought waves probably pass readily thru the human skull. If once we admit this theory it follows that it should be possible to detect such waves, and the only thing we need to know about them are the wave length and other important characteristics. We may take it for granted that the human brain, sensitive as it is, probably is not at all sensitive to these waves, and that by suitable apparatus it should become possible to detect such

Just what apparatus are necessary to detect thought waves, or the effects therefrom, the writer does not venture to predict, but there is no doubt that the apparatus will be eventually found. Very little is known about the emission of the thought waves, and as a matter of fact the entire mechanism which produces thoughts is practically an unknown quantity, but every effect can be translated and recorded if once understand its fundamentals.

Thus, fifty years ago the recording of the waves. we All voice would have appeared just as fantastic as the recording of thought appears today. People then rightly said, how could it be possible to hold the spoken word; it goes into the air and vanishes instantly. But once acoustics were better understood, it became a simple matter for the inventor of the phonograph to record the voice. Similarly, the day will come when thoughts will be recorded in an analogous manner. that is necessary, as stated above, is suitable apparatus, and this should be easy to find. The writer, in suggesting the audion as a thought-wave detector, does not do so because he thinks that it is suitable in all respects, or even feasible. His main idea is to set the stone rolling, and get other people to think about the problem, when sooner or later something surely will emerge.

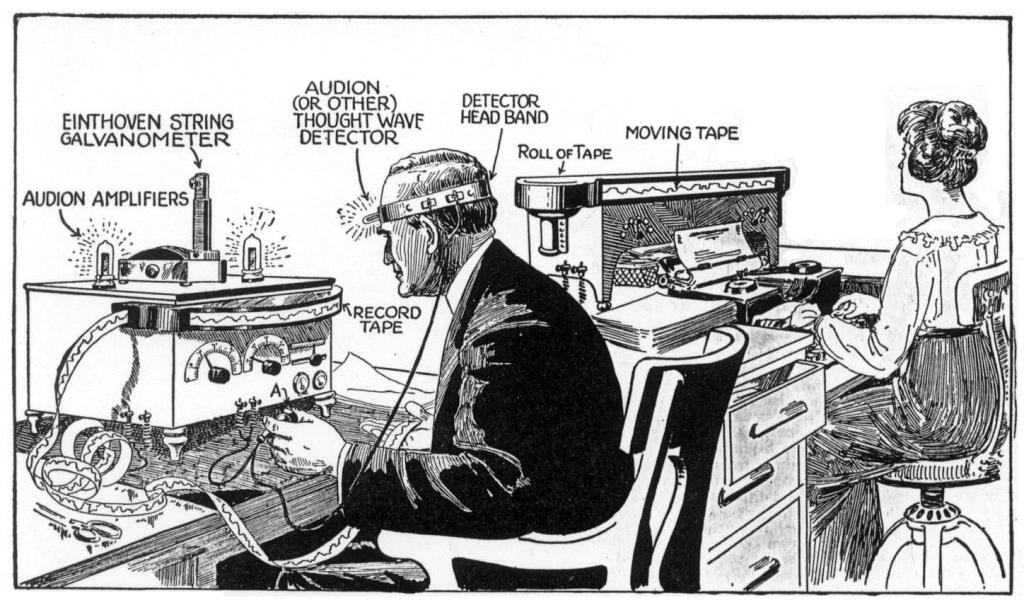

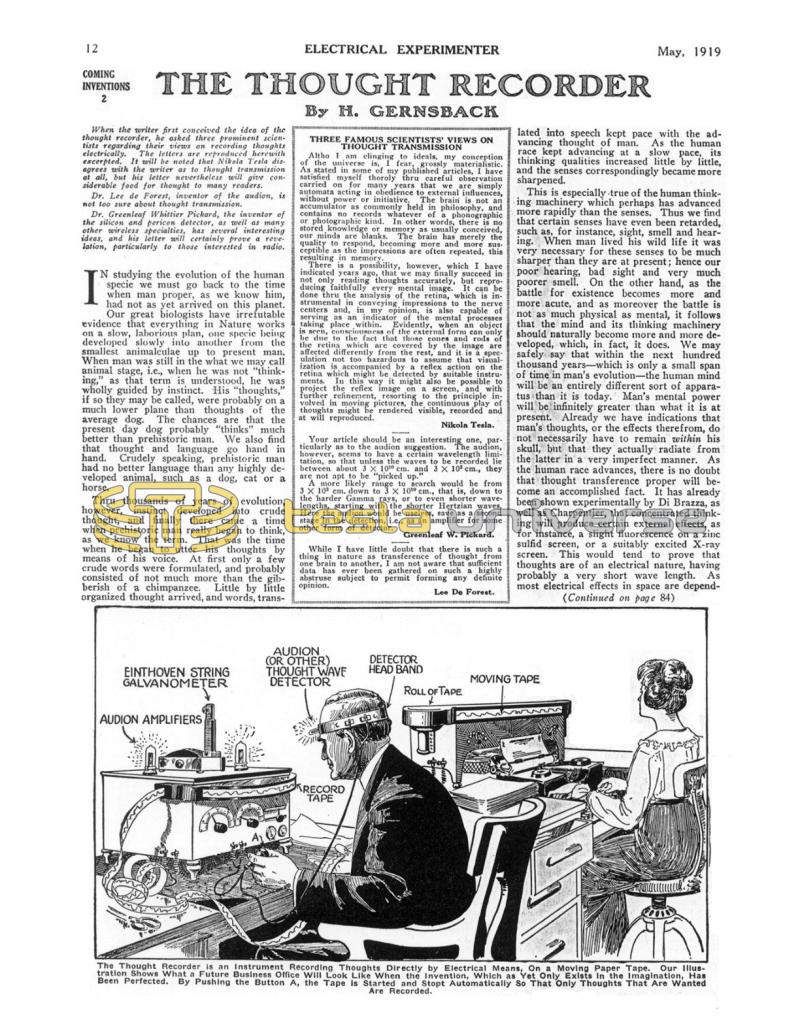

The writer has suggested the audion because it is known as one of the most sensitive electrical detecting apparatus for wave motion which we have today. If thoughts give rise to electrical waves, then by winding a few turns of wire on a headband and slipping it over the head, it should be possible to detect the presence of thought waves in the audion. On the other hand, too, the audion is enormously sensitive to capacity effects, as is well known. Thus, for instance, an oscillating audion is so sensitive that when the human hand is approached to it at a distance of even two feet, the presence of the hand will be heard plainly in the telephone receiver. If this is the case, the disturbance created in the mind should certainly make its presence felt in the audion, for thinking being first of a chemical nature, the act certainly must give rise to capacity effects. But let us assume that active thinking does not give rise to waves, electrical or otherwise, then the mere chemical action (and resulting capacity effects) should produce a disturbing influence upon the audion. These variations, if ever so slight, could then be amplified by the use of an audion or other amplifier, and the resultant effect be sent into an Einthoven string galvanometer. The small mirror attached to the string of the galvanometer will send its luminous pencil upon a light-sensitive paper tape which moves at a certain rate of speed in front of the mirror. The result will be a wavy line traced upon the paper tape in the well-known manner. The paper tape traveling on will pass thru its fixing tank, and from there will emerge from the outside of the machine after it has past thru a small drying chamber heated by electrical coils.

From this, it will be understood that a man sitting in front of his Thought Recorder will be able to actually see on a tape his recorded thoughts, the same as the telegrapher working on a trans-Atlantic cable watches his tape and its wavy line produced by the Syphon recorder, emerging from the latter. Of course, it will be necessary for everyone to learn the "thought alphabet" just as the stenographer today must learn the various characters, or as the child is taught how to read and write, and as the cable operator must learn how to read the Syphon recorder "alphabet." All this, however, is simple, and is only an educational feature once the apparatus has been invented.

The objection naturally comes to the mind immediately that even if we have a machine to record the thoughts, all we will get on the tape will be a jumble of confused thoughts, and we might get a lot of things on the tape that were not meant for recording or registering at all. Such criticism, of course, is beyond controversy for the simple reason that when you write a letter by hand or on the typewriter, you have also at first a lot of confused thoughts, but you do not record such thoughts even by hand or by machine. It often happens after you have written down certain thoughts that you must change them. The same is true of the thought recorder, of course.

Here the man who is doing the recording has a push button in his hand, shown at A in our illustration; if he does not press the button nothing is recorded. Once he wishes to record his thoughts in an orderly manner, he pushes the button and the tape begins moving simultaneously — he will begin thinking in an orderly and slow manner the subject he wishes to record. He will think just as hard and just the same as if he were to pen down his thoughts by hand. The machine will then do the rest. If he thinks the wrong thoughts, naturally the wrong thoughts will be recorded, exactly the same as if he had written them by hand. There is no difference. In our illustration, our artist has endeavored to show what will happen in the future business office when the thought recorder comes into universal use. The business man of tomorrow will dictate his correspondence on the thought recorder, while his stenographer, who is perfectly familiar with his "thought writing," will type out the correspondence from the tape, which is kept moving by electric motors, in front of her eyes. A foot pedal stops or starts the motor, and there is also a reversing attachment so the tape will run backwards should she wish to re-read a certain portion of the tape.