Nikola Tesla Articles

What Electricity Will do for Us

The Successful Utilization of Niagara Power - Cheap Transmission to Buffalo — Progress in House-Lighting, Factory Work, etc., etc.

Written for the Express by Madison Buell.

No name is more brilliantly associated with recent progress in electricity than that of Tesla, the Italian who is astonishing the world with his discoveries and wonderful experiments in electrical science. He has given us new thoughts and his experiments have developed and corrected all former notions of the science — given it a new character from that ever before conceived. He has opened a new field of vision, which, in its turn, has to be explored and verified, and which again may lead to newer extensions and developments.

Tesla has, during his many experiments, demonstrated the fact, that one can, under certain conditions, receive unhurt electric currents of hundreds of thousands of volts, and he has lighted up tubes and lamps through his body; rendered long wires entirely luminous; showed motors running under the influence of the million frequency currents; obtained magnificent effects with phosphorescent lamps; and he has often demonstrated how little, in such work, the high resistance of the carbon filament has to do with the lighting up of the ordinary 50 or 110 volt lamp.

His ability to produce such effects, either with a single wire and no return, or without any wires at all, arouses the utmost interest and enthusiasm wherever witnessed. In regard to the physiological effects produced with high-tension, high-frequency currents, it may be said, that a great amount of energy may be sent into the body of a person by their means, because it is dissipated laterally from the body and not passed through in the direct manner involved in the use of low frequency currents. It is due to the intense rapidity of vibration that Tesla has received with impunity currents as high as 250,000 and 300,000 volts, an amount which otherwise administered would kill him.

Tesla is a firm believer in the transmission of power from Niagara, and believes the time is propitious to see great powers transmitted long distances and over one wire.

If there are any in Buffalo who are skeptical in regard to the success of the transmission of power from Niagara, what will they think or say when they are told that a man like Tesla, says: "the distribution of electrical energy with something like 100,000 volt, and even more, become, at least with high frequencies, so easy that they could With oll hardly be called engineering feats. Insulation and alternate current motors, transmissions of power can be effected with safety and upon an industrial basis at distances as much as a thousand miles." Yet there are — or have been — skeptics in Buffalo who declared that the Niagara project will not be a commercial success.

Probably it is well to go a step further and tell them what Tesla thinks of the future. "Alternate currents, especially of high frequencies, pass with astonishing freedom through even slightly rarefied gases. The upper strata of the air are rarefied. To reach a number of miles out into space requires the overcoming of difficulties of a merely mechanical nature. There is no doubt that by the enormous potentials obtainable by the use of high frequencies and oil insulation, luminous discharges might be passed through many miles of rarefied air, and that, by thus directing the energy of many hundreds or thousands of horse-power, motors or lamps might be operated at considerable distances from stationary sources. Such schemes are mentioned merely as possibilities. We shall have no need to transmit power in this way. We shall have no need to transmit power at all. Ere many generations pass, our machinery will be driven by a power obtainable at any point of the universe. It is a mere question of time, when men will succeed in attaching their machinery to the very wheelwork of Nature."

Prof. Forbes, the consulting electrical engineer for the Niagara project, is impressing upon the English people the importance of their stopping over at Niagara Falls, when they are on their way to visit the Chicago Exhibition. He desires them to see for themselves the way in which the "vast forces are being harnessed to the service of man." He tells them that he has no hesitation in making the statement of a complete success of the utilization of Niagara, and assuring them that the cost at which a horse-power per annum can be sold in the neighborhood of Niagara, or at Buffalo, is "such as to make the enterprise a certain success from a commercial point of view."

In speaking of the electrical part of the scheme, he says: "I feel some diffidence, because we are at the present moment on the eve of settling the type of machinery to be used. I have before me for consideration more than 20 distinct plans of the 5,000 h. p. generators which may be used. Some of these are for continuous currents, others for alternating currents; and while I naturally have definite views as to which of the plans proposed is the most practical, I confess that, even at this time, I have an open mind which would be free to accept anything which seems more valuable than the best design we have received as yet. Of one point I may assure you most definitely, and that is, that there is not the slightest difficulty in making this work successful from an engineering as well as from a commercial point of view. My difficulties have consisted chiefly in the number of different ways by means of which it was possible to attain the results required. The types of machine which have been proposed vary in many essential features, and in none more than in the important item of the weight of the revolving part, which varies in these designs from seven or eight tons up to 60 tons; but it is quite remarkable that in a science of comparatively recent growth, as in the distribution of power electrically, there should be so few differences of opinion as to the means to be adopted, and the character of the machinery to be used. . . . It is consequently a little surprising that electricians are so nearly agreed as to the methods and machinery to be used."

The general reader will observe that Prof. Forbes uses the words "continuous currents" and "alternating currents;" and as Buffalo in the near future is to be the great electrical city of the world, it may be interesting to some of her people to know and for them to understand what these terms mean.

The term "dynamo-electric machine," broadly used, denotes an apparatus in which, by the agency of what is termed electro-magnetic Induction, mechanical energy of rotation is converted into the energy of an electric current; or inversely, the energy of such currents is converted into mechanical energy; and the definition holds good whether the current given out by the machine when driven by power from a prime mover is always flowing in the same direction, or is alternately flowing in opposite directions. It also holds good for a machine which is driven by a current supplied to it from an external source, whether the current is always flowing in the same direction, or whether the flow is periodically reversed.

For all practical purposes the term "dynamo-electric-machine" is divided into four classes of machines. First, the dynamo, in which mechanical energy of rotation is converted into the energy of a direct or continuous current. Second, the alternator, in which mechanical energy of rotation is converted into the energy of an alternating current, i. e., flowing alternately in opposite directions. Third, the motor, in which the energy of a direct current is converted into mechanical energy of rotation. And fourth, the alternate current motor, in which the energy of one or more alternating currents is converted into mechanical energy of rotation.

Any one of these four types of apparatus has for its object the conversion of energy from one form into another form. The commercial value of such machines depends upon the ratio between the amount of energy supplied in one form, and the amount obtained in another form. In all classes of machinery losses take place, but in electrical apparatus of this kind the loss is much smaller than in other mechanical appliances.

Dynamos can be built having an efficiency of 90 per cent., whereas in steam engines an efficiency of 75 per cent. is exceptionally high. The dynamo-electric machine is unquestionably the most efficient apparatus at present known in mechanics, and if Buffalo is great now in her days of prosperity, this class of machinery is destined to make her surpassingly great during the next five years.

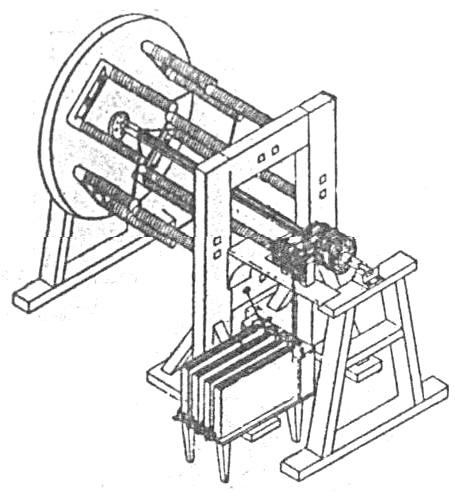

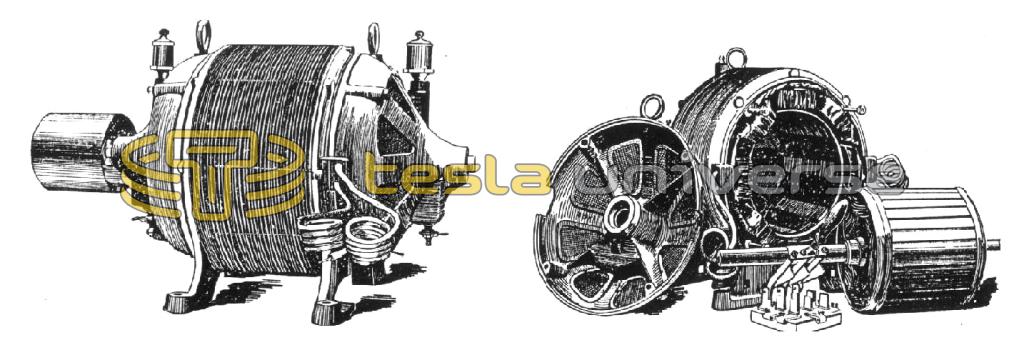

A trifle over ten years ago, such dynamo- electric machines as were made were of the kind more suitable for the laboratory than for the workshop. They were of small power and imperfectly designed, both electrically and mechanically. They were not made by engineers, but by electricians accustomed to make all kinds of small electric apparatus, and they did not realize the magnitude of the mechanical forces with which they might have to deal in a properly-designed dynamo. After Faraday, in 1831, announced his great discovery of electro-magnetic induction, Pixil produced a magneto-electric machine for alternating and direct currents. He was followed by Henry and Jacobi in 1834. A sketch of Jacobi's motor is given both for comparison and curiosity. Up to 1864 there was a continuous record of improvements, when Pacinnoti made the great invention of the closed armature circuit and commutator; and in 1870 Gramme reinvented the same thing, but Gramme, being a skilled workman, gave practical shape to his invention in the dynamo which bears his name, and which is the prototype of all dynamos with closed-coil armatures.

Today the power of our dynamos and alternators is reckoned by thousands of horse-power. The tendency is in the direction of enormous and powerful machines, and they can only be made in engineering shops fitted with the best of tools and appliances. Apparatus of such magnitude cannot, as in the early days, be made by the rule of thumb" method of construction. An illustration of the enormous size of the modern dynamo-electric machine of 1893 is given, and the reader may be able to judge of the progress made in the science by comparing it with the Henry apparatus of 1831.

The success of the Niagara project depends upon machinery of this magnitude, and whilst Henry's apparatus is an illustration of the work of a man who studies "science for its own sake," and without regard to practical applications, the modern dynamo-electric machine shows the work of the scientific engineer, who by his knowledge of nature is able to deal with new "engineering problems," and to provide useful solutions when they are presented to him. But an "engineer may be scientific, inasmuch as he has knowledge of nature and the power of applying that knowledge: and he may be practical in the sense that he devises means. to attain his ends." But what bears directly upon the utilization of Niagara," and the success of the scheme may be summed up in the following words: "The complete engineer must give his attention to commercial matters as well; he must know when he has devised the means to attain the if, ends in view, those ends when attained will result in a profit. He must recognize the conditions which render an undertaking so secure that it shall bring in a large return."

Men like Prof. Coleman Sellers, whose knowledge and experience of all classes of machinery; Clemens Herschel, who has devoted his life to the development of hydraulic enterprises; Turretini of Geneva, Burbank and Porter of Niagara Falls and Prof. Forbes of England are not men to engage in such an enterprise as the utilization of Niagara unless sure that it would result in a commercial success.

Prof. Forbes вауs: "A great number of applications for power have already been received, and it becomes perfectly evident that the establishment of each separate industry will bring to the neighborhood a large number of new industries. Thus we expect very shortly to have a copper refinery for electrolytic processes. This will naturally bring wire manufactories to the spot. Electric cables will also be made there, where the wire can can be obtained cheapest. The wants of the company alone are sufficient to require the establishment of an electrical factory, and the facilities for transporting machinery by land or water will be such as to make it an important center for the manufacture of large electric machinery, either for lighting, for traction or other purposes. And so it appears likely to proceed, the success of one industry leading to the establishment of another, until the whole land of the company, and much more besides, is used up in the raising of what may eventually become the greatest manufacturing center of the United States.

"In order to give facilities of transport to those who establish themselves here, ample wharfage accommodation will be established, a matter which is comparatively easy, since the company owns several miles of river frontage. With the same object in view a terminal railway has been built, and is now at work, connecting the principal streets belonging to the company with the three great lines of railroad which pass beside it. Contracts have already been given out for the construction of laborers' houses, and before long this part of the new city will have made sensible progress.

"The company has also undertaken the water supply of the city, including the old part, which was insufficiently supplied, they are also dealing with the matter of sewerage.

"Altogether I may briefly state the impression which has been thrust upon me by an examination of the plans and works of the company, in saying that they have taken a most comprehensive view of the situation, and have proceeded up to the present with an amount of caution and foresight that cannot but augur well for the future of the enterprise.

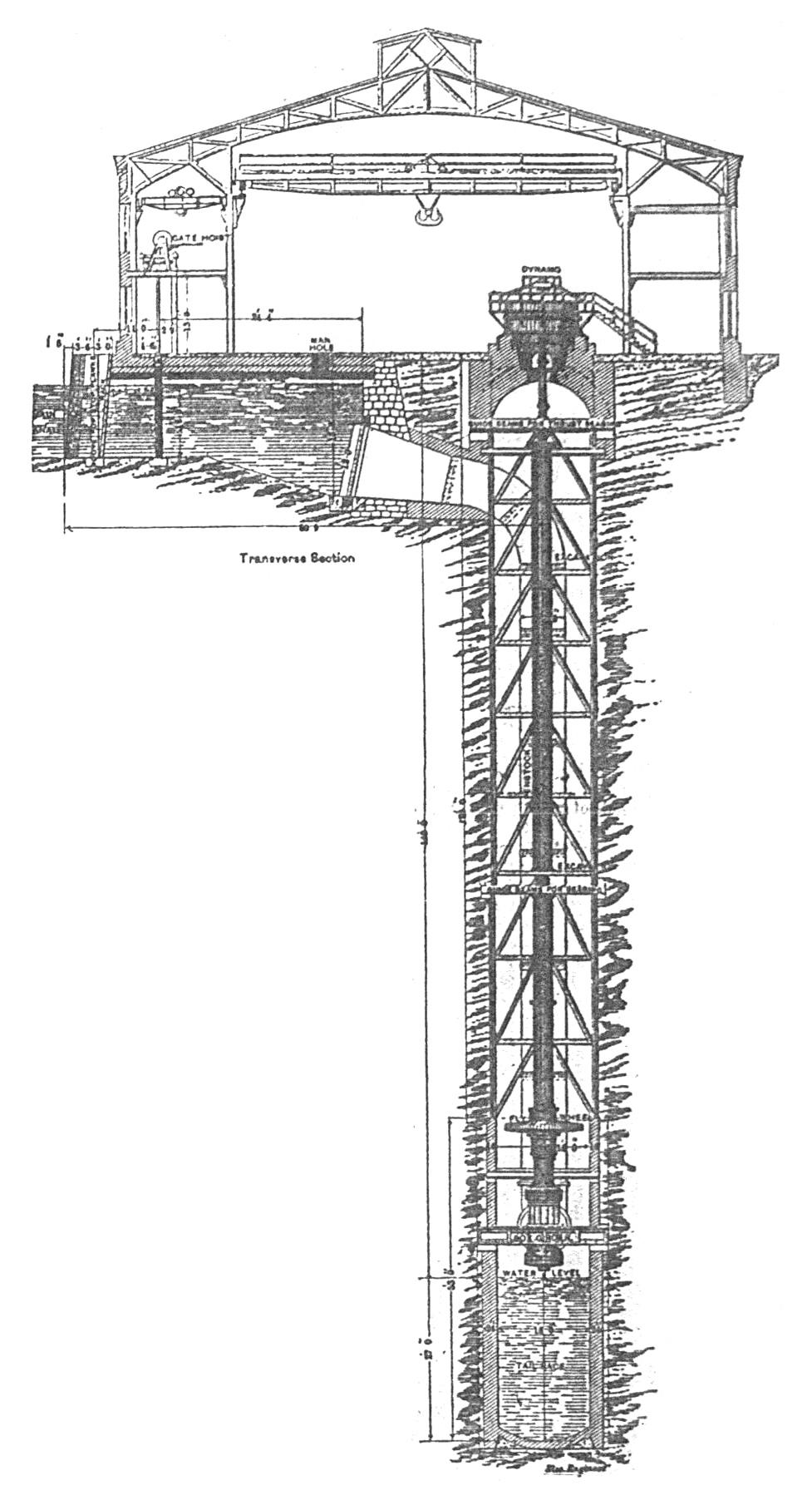

"The Cataract Construction Company has already sunk a shaft sufficient to accommodate three of the 5,000 h. p. turbines which are to be used for the work of distributing light and power. Considerable difficulty was met with in sinking this shaft, by the influx of water through a seam at a depth of about 30 feet below the surface. These difficulties have never interfered with the progress of the work, which has now been successfully carried out. The turbines which are to be used are of 5,000 h. p., revolving at 250 revolutions per minute, of the Girard or impulse type, with a regulator for adjusting the flow of water. Each turbine is double. Attached to the shafts of the turbines are vertical shafts, extending to the surface of the ground, and on the top of these shafts the dynamos are to be mounted, which will transmit electricity, for light and power purposes, to the surrounding districts and to Buffalo. The turbines are from the designs of Messrs. Faesch and Piccard of Geneva, who transmitted the working drawings to America; and the contract for these turbines has now. been given out to the I. P. Morris Company of Philadelphia, two turbines having been ordered in the first instance. Twenty of these will be required to utilize the full capacity of the tunnel, which is 100,000 h. p."

The electrical utilization of Niagara, is an assured fact, for all the "fundamental elements required for electrical transmission in a wide range of cases" have been tried with perfect success. They have passed from "experimental investigation into practical engineering." But what a sublime moment it will be for Buffalo, when the victory of grasping and controlling the "waste forces" of What a contrast, the Buffalo of 1798, with Niagara has been won! Buffalo of 1847 and 1893, will be with that of 1,900! What was Buffalo 95 years ago? "A double log-house, about two squares from Main Street, a little north of Exchange Street, a half log and frame house a little east of the present Mansion House, near Washington Street, a two-story hewed log-house on Exchange Street, from six to eight rods of west of Main Street," which was a tavern kept by a man named Palmer —" an Indian store in a log building on the west side of Main Street north of Exchange Street," and one or two other log-houses, was all of Buffalo In 1798.

Three years afterwards Palmer, who kept the tavern, wrote to Joseph Ellicott the following letter — (this was the first step in an educational line):

"Sir: — The inhabitants of this place would take it as a particular favor, if you would grant them the liberty of raising a school-house on any lot, in any part of the town, as the New-York Missionary Society have been s good as to furnish them with a school-master, clear of any expense, except boarding, and finding him a school-house; if you will be so good as to grant them that favor, which they will take as a particular mark of esteem."

Palmer added to it: "N. B. Your answer to this would very acceptable, as they had the timber ready to hew out."

Up to 1820, "no lake craft larger than a canoe or French bateau had entered the mouth of Buffalo Creek. The stinted commerce of the lakes had no harbor at the foot of Lake Erie, except Black Rock; vessels discharging freight destined for Buffalo, or taking freight from there, did it at Black Rock, or, laying off the mouth of Buffalo Creek, received and discharged freight by means of small boats."

In 1822 the steamer Superior was built and [Continued on page 3.] she was the pioneer of Buffalo commerce.

In 1847 there were in commission upon the lakes, 98 steamers, 35 propellers, four barges, 82 brigs, 495 schooners, 23 sloops and scows, a total tonnage of 131,460 tons" "The total value of imports of Buffalo from the lakes in 1846 was nearly $20,000,000. The total value of the business of Buffalo and Black Rock, done on the canal, which came from and went on the lakes was $40,000,000. The number of passengers arriving and departing from Buffalo in 1846 was 250,000.

The writer when a boy, in 1846-1847, never neglected to board every steamer or propeller that came into Buffalo Harbor. He has trod the decks of the steamers Superior, Great Westeru, Julia Palmer, United States, Sultana, Indiana, Illinois, Albany, Empire State and a host of others. Who is there of the present generation that can say the same? Buffalo today is a city of 300,000 inhabitants. What will it be in 1900?

Electricity the prevailing spirit, and Buffalo her especial shrine: the whole region around and above her will be one continual effervescence of energy. At night, she will be so magnificently illuminated that the heavens will be a grand sight, equalling in splendor an auroral display; the gorgeous rays of gold, the phosphorescent sheen of the milky-white columns, gleaming bright with rosy blushes, will chase each other up and down the zenith, till the whole heavens shine with the mysterious light; green, yellow and red flames will mingle in every direction, and the constant blaze of the bright flashes of light will fully demonstrate to the surrounding towns that Buffalo is indeed the wonderful Electrical City of the World.

Propositions are now being entertained as to the best electrical method for converting the power and transmitting it in the immediate neighborhood of Niagara Falls and to Buffalo. It is supposed that the rate will be $10 per year per horse-power for 5,000 horse-power or over; $10.50 for 4,500 horse-power; $11 for 4.000 horse-power, and so on down to $21 for 300 horse-power, it being understood that all these estimates are based upon 24 hours' dally use of the current if needed. These rates may be contrasted with the expense of steam-power for a 10-hour day, ranging from $25 to $40. So far as the rates are concerned, it is not known whether these figures include electrical transmission to Buffalo or not; the exact figures will not be given out until the plant is in operation.

Prof. Forbes has given it as his opinion that the power will cost "so much less in Buffalo than that, derived from steam plants that it will be an extra inducement" for consumers in this city to use it. "The running expenses" at the Falls" will be a mere nothing; the amount of attention will be small, and the work has been so carefully supervised that it will be almost impossible for any accidents to occur."

The application of electric power from Niagara will enormously increase our growth in every direction. Every industry in the city will have its electric motor, and every day will bring into light some new and novel application of electrical energy. Buffalo and her industries will be the daily tople of conversation of the people in nearly every town and city. and upon their lips will often be heard the words: "Hear ye not the hum of mighty workings?"

The great success of the electric street and suburban roads will be such that the public will, in addition to passenger facilities, demand that of freight transportation. And it will be a daily occurrence to see electric freight Cars going over the different roads, destined for the suburbs and outlying towns.

As soon as Hamburg, Williamsville, Lancaster and Tonawanda realize the benefits conferred upon then by the electrical passenger railway, the demand will be made upon such companies for the freight service. It will only be a matter of a few months after these roads are opened for them to secure contracts for carrying the U. 8. malls in and out of Buffalo, and the companies deriving Federal protection will be amply repaid thereby.

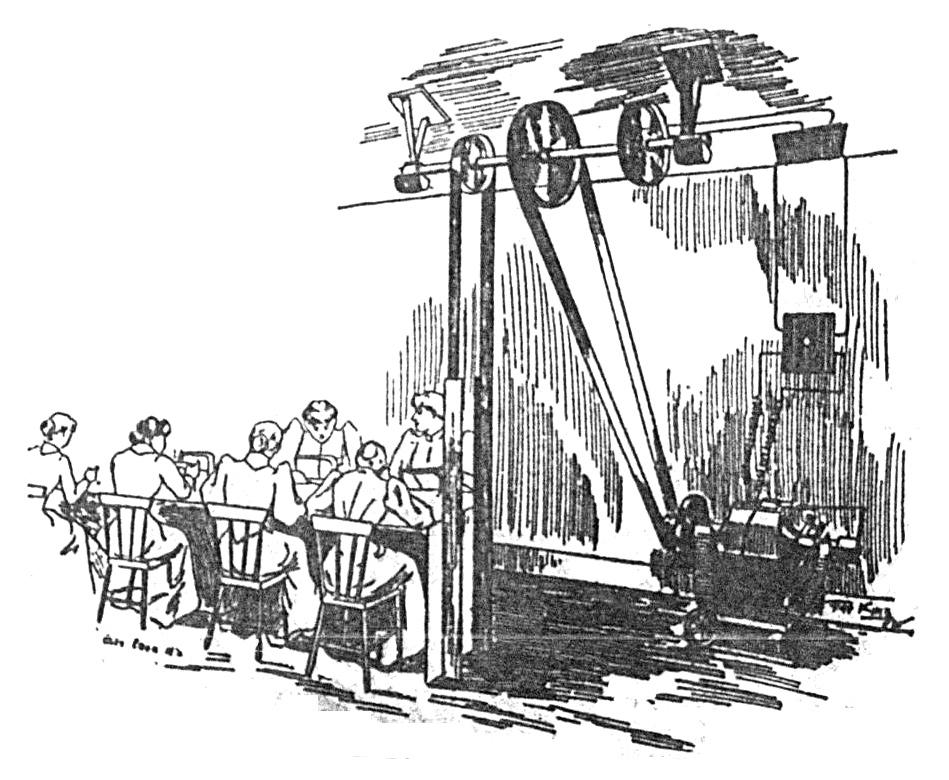

A road of this character is now in operation from Thomaston to Camden, Me., a distance of nine and one half miles. The style of car used weighs a little over 15 tons and has a carrying capacity of 20,000 pounds. The road itself is built in a most substantial manner, the idea of a freight service having been contemplated from the outset. There is no reason why all the freight traffic between Buffalo and outlying towns should not be done on our electric roads.

When we get our electrical energy from the Falls our machine-shops will be revolutionized. The great mass of leather belting that now fills them, like moving mats of lattice-work, will be abolished. Electric motors will run the enormous lathes, and also the huge cranes, capable of moving great masses of metal, far beyond anything of a like character at present in use, though we now have them capable of moving over 40,000 pounds with ease. The hot furnaces, foaming boilers and dangerous engines will all be relegated to the scrap pile.

Buildings of any size will have their electric elevators, and one of the most important applications of electrical power will be in the operation of all kinds of elevators and hoist ing machines. All of our principal grain elevators with their enormous capacity for handling grain will be thoroughly electrically equipped for that purpose. The liability of elevator fires will be greatly reduced.

The motor will be brought into private houses, where safety and noiselessness are essential, for elevator work.

The electrical pump will become an essential feature wherever it can be used; and no doubt can be entertained that eventually all the pumping of the Niagara water for city purposes will be done by electric-power — power derived from the water itself! The electrical energy will be used for almost every purpose to which steam is now applied. Our 'manufactures and others "mindful of great profits derivable from reduction in expenditures for power," to say nothing of the entire freedom from dirt, oil and smells, will adopt the motor. The long lines of shafting with all the evils of copious lubrication and "costly friction, heavy and expensive belting in complex systems" with large and small pulleys innumerable, will be forever discarded.

There will be a remarkable growth in incandescent lighting, and it will come into constant use in all of our modern residences, not only In those now erected, but in all hereafter to be constructed. The wealthy will desire to "break away from the stiff and conventional ideas embodied in the traditions and practice of what we may call the gas era, and to rescue decorations, books, pictures and tapestries from the quick detriment due to the conditions created by gas in process of consumption."

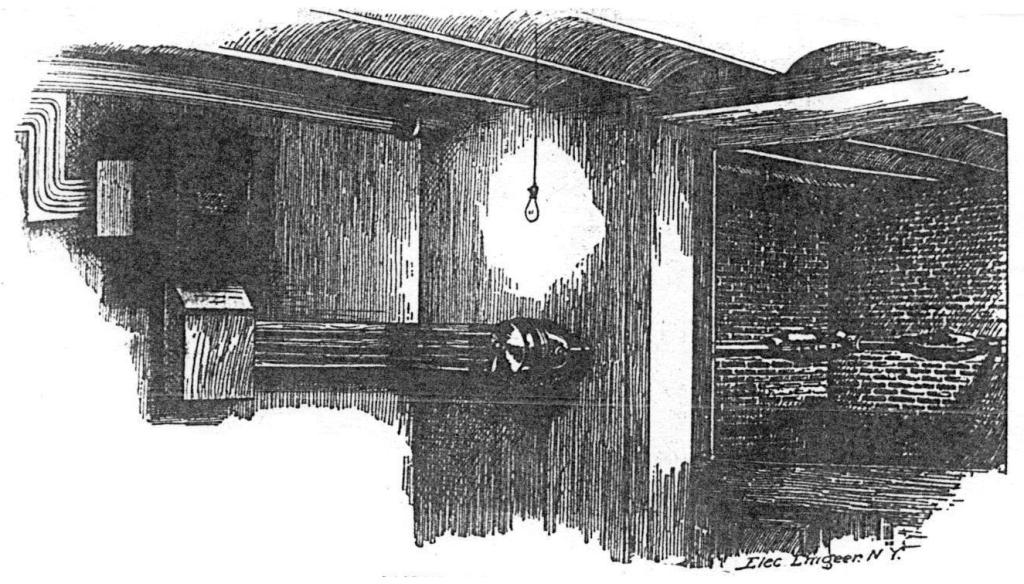

The architect of today has, for Buffalo, a brilliant opportunity for material improvement, "by studying the highest aesthetic effects that may be reached with correct taste and judgment in this line. Illustrations of what may be done show the advance already made in modern electrical engineering in this direction. Wires from the street may be brought into a vault in the basement or cellar, and are first passed. through a switch-coupling; thence carried to the meter, which records the consumption of the current for any and all purposes. The switch should be hermetically sealed, so that water can flow over it or around it without injurious effect. One illustration shows a large hall with a broad stairway set with palms. The lights in the drawing room and other rooms are controlled from the large switch board shown in this sketch. "The situation is eminently accessible, and yet when the door is closed, the mahogany paneling appears to be intact." When the panel door is open. the board is "an ornamental and highly finished piece of work, with polished slate base and all details in brass."

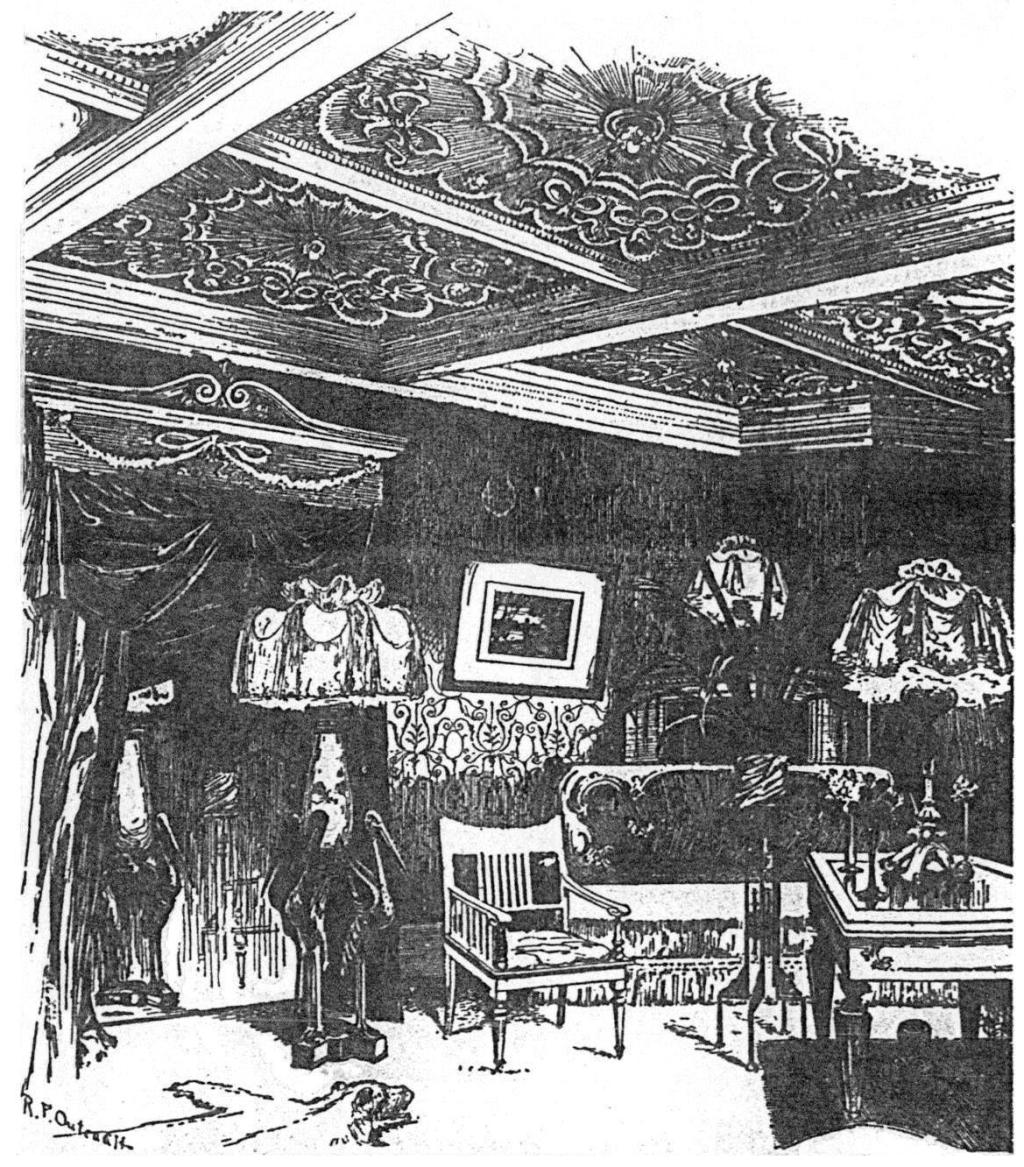

The exquisite illustration of the drawing-room, "reveals conspicuously an emancipation from all the old ideas prevalent as to methods of lighting, and a very successful experiment in the treatment of light itself, as something fluent and plastic, capable of being distributed for obtaining soft and harmonious effects." Under the regime of electrollers and massive fixtures it could never be obtained. In this drawing room there is not a single bracket or fixture of any kind; the decorations are white and gold, and the frosted lamps set in the ceiling panels in delicate tulip cups, do not strike the eye individually. "We have not lights, but light." In addition, each of the ornamental lamps disposed of casually about the room carries not only a light under its canopy, but one within the body of the hand-painted vase.

Our architects have in these illustrations an object-lesson of the first importance, and the study of them by the wealthy will teach them what there is in the modern method of utilizing electric light in the House Beautiful, and they can give the freest play to taste and genius.

Some years ago, a statement was made which was deemed a "wild and exuberant flight of fancy," and yet today is a realization.

"It will be possible," wrote this prophet, "for a man to drink at breakfast coffee ground and eat fruit evaporated by electric power. During the morning he will conduct his business with electrically-made pens and paper ruled by electricity, and make his records in electrically-bound books, his seventh-story office, in all probability, being reached by an electric-motor elevator. At luncheon he will be able to discuss sausages, butter and bread, and at night eat ice cream and drink iced water due to the same electrical energy. He will ride all about the place in electric cars, wear shirts and collars mangled and ironed by electric motors, sport in a suit of clothes sewn and a hat blocked by the same means; on holidays ride a merry-go-round propelled by an electric motor, or have his toboggan hauled up the slide with equal facility; be called to church by an electrically-tapped bell, sing hymns to the accompaniment of an electrically-blown organ. be buried in a coffin of electric make, and, last of all, have his name carved on his tombstone by the same subtile, mysterious, all-persuasive and indefatigable agency."

What is this all-persuasive and indefatigable agency"? The natural sources of energy available for the wants of man are coal and oil pent up in the bowels of the earth, and water accumulated in the higher levels of the land. Energy is expended when coal is burnt and the water falls, and all of our available energy by their use is derived from the sun. Coal is solidified sunlight. Water is condensed sunshine. We mine our coal and liberate our "preserved sunlight," and whenever we can interfere with Nature, we tap our "condensed sunshine," and from the two utilize their energy, for dally use. So, for all practicable purposes, whenever the question is asked, "What is electricity?" it can be answered, "Principally coal, and sometimes water."

"Five pounds of coal consumed in a furnace, per hour flashes 50 pounds of water into steam. The steam in its reconversion to water transfers its energy to a moving mass of machinery, a part of which consists of copper wires forming a portion of an electric circuit. The wires rotate in a magnetic field where work is done on them, and where, in consequence, the mechanical energy of motion is converted into molecular energy of electricity. The five pounds of coal have produced 1 1/8 h. p., or 1,000 watts in the circuit; in fact, a kilowatt is the scientific unit of power. A watt is the energy expended by an ampere when driven by a volt. It is equivalent to nearly three fourths (actually 0.737) of a foot pound." The ampere is the unit current, and the volt the unit of electrical pressure. A 16-candle lamp requires 100 volts and 0.48 amperes to bring it into brilliancy. It absorbs 48 watts and therefore 1. c. p. is produced by three watts. A kilowatt hour uniformly expended gives 333 candles continuously, or it will maintain 21 lamps alight; or, if the light be not needed, then the kilowatt of energy can be converted into other forms of energy, as I have already named.

Now, what has all this to do with Buffalo's profit from the utilization of Niagara's power?

How many people in this city realize the fact, or know the total power developed at the falls? How many believe that "4,500,000 h. p. is developed," or that the falls represent "the equivalent of all the steam-power used in the world?"

"It takes five pounds of coal to generate one horse-power for an hour. This water-power is the equivalent of 15,000,000 tons per annum." One is not struck so much by the volume of water that shoots over the precipice, as by the immensity of the power of heat, which is able to evaporate and carry to the great lakes by the winds a volume of water of such magnitude. The enthusiastic spirit of a scientific engineer realizes at once "that the falls is the most gigantic condensing steam engine in the world, of 4,500,000 horse-power. The power in the falls acts as a furnace; the mass velocity of the water acquired by the fall is arrested and converted by fluid friction into molecular velocity, which is heat. The lower river and ocean form the boiler. from which the heated water evaporates; the wind is the engine, by which the steam is carried to the condensers, which are the great lakes. The work done is the work of raising a thousand million pounds weight of steam from the lower river and ocean, to be eventually deposited in the upper lakes every minute of time — not necessarily the same atoms of steam, but their equivalent."

Starting from this grand spectacle of natural force, all other manifestations of force will, when electrically utilized here, set all forces in motion; "not in one way merely, but many ways. It will be as with the weaver's web,

"Where a step stirs a thousand threads,

The shuttles shoot from side to side,

The fibers flow unseen,

And one shock strikes a thousand combinations."

After Buffalo becomes renowned throughout the whole civilized world, by the success of this electrical achievement, what does all the tremendous energy received by her amount to, compared to the principle of the energy exhibited by one of the lowest insects that dances upon God's foot-stool and charms all human eyes by its luminosity?

There are two spots in the segment of the abdomen of the glow-worm that are more luminous than any other part, and a constant vibratory motion of this segment emits a light. Its energy is transmitted in the same manner as that of the sun, through an ethereal medium, and it gives light of such a character as to affect the retina of the eye. It is an electrical effect, and it is only one of the many forms that sends it out on its ceaseless journey. The secret workings of the marvelous light contained within the segments of the abdomen of the glow-worm is being imitated, and will yet be the means of obtaining an energy that will light a thousand lamps at a touch.

If we now have one glorious ethereal glow by day, that illumes with its fluid gold, this "world of ours that hangs like a pendant fast by a golden chain in space," when we solve the problem of the glow-worm, then at night we can have "s confluence of ethereal fires that will rival the energy of the light that comes from lamps unnumbered down the steep of heaven."

MADISON BUELL