Nikola Tesla Articles

The World of Tomorrow - Interview with Nikola Tesla (INCOMPLETE)

Webmaster note: This article is incomplete, but because of its uniqueness, it is being posted as-is with the hope that someone will be able to help locate the missing portion. If you have any information, please contact us.

An Interview With Nikola Tesla

Dr. Tesla, world-famous inventor, electrical wizard, and scientific forecaster unfolds the curtain of the very near future. "We are now watching the inauguration of a tremendous revolution," he says.

To spend an hour with Dr. Tesla, as I did the other evening, is like soaring high above the clouds in an aeroplane, or viewing the earth from a distant mountain top.

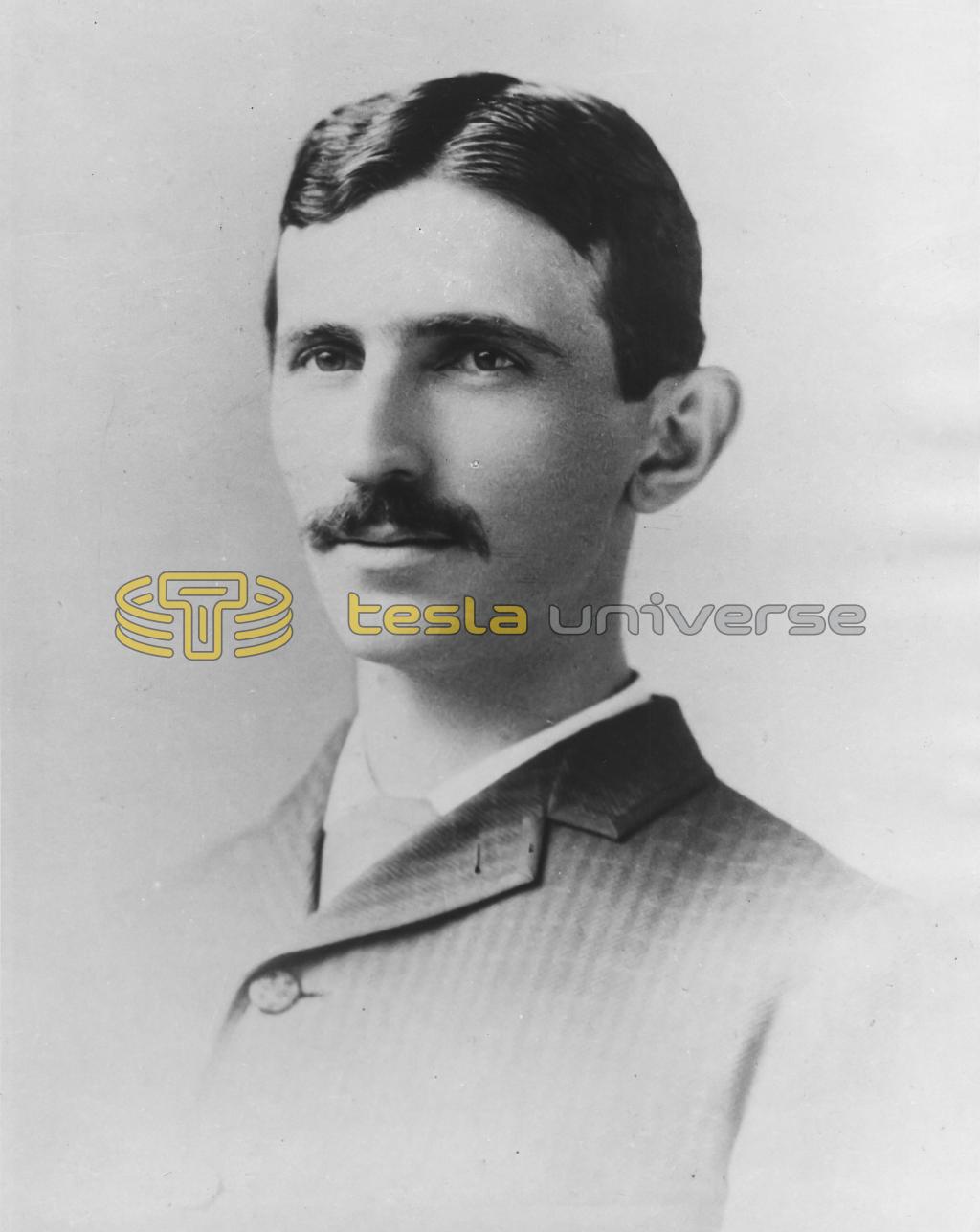

At seventy-seven, Dr. Tesla looks out upon the world he has done so much to revolutionize and forecasts even greater changes within the very near future. Like the infrared ray, his deep-set, blue eyes pierce the fog of ignorance that engulfs us.

Tall, thin, ascetic, he towers high above the masses. But his interests remain closely interwoven with their welfare. Never does his gaze leave the drama of their daily living.

His entire thought is centered upon making that drama more beautiful and satisfying to all humanity.

"The desire that guides me in all I do," Dr. Tesla told me, "is the desire to harness the forces of nature to the service of mankind."

As he sat there, unfolding the curtain on the future and recalling the conflict of his early years, I was struck by the happy, youthful gleam in his eye, the serenity of his long, delicately chiseled face, the fine, slender lines of his hands. Those hands are the hands of an artist; that face the face of a philosopher, a poet, a dreamer. But Dr. Tesla is more than that. He is a practical scientist who converts his dreams into realities — realities that have startled the world and will do so many times again.

"We are now watching the inauguration of a tremendous revolution," he told me. "It hinges upon the commercialization of the wireless transmission of power, the principles of which I have discovered. As soon as this is done, distance will be practically eliminated. And just think what that means — the end of the misunderstanding that is at the base of all of our present troubles. Up to now, individuals and nations never have been able really to come together. Wireless will make that possible. It will largely obliterate international boundaries and harmonize conflicting national interests. It will create understanding and sympathy, where now misunderstanding and antagonism reign.

"When wireless energy is commercialized, transport and transmission will be revolutionized. Motion pictures will be carried illimitable distances by wireless. Flying machines will be propelled by the same energy. We shall be able to fly from New York to Europe, with perfect safety, in a few short hours. We shall be able to go anywhere in the world — to the highest mountain, to the arctic, the desert, the jungle — and set up a little equipment that will give us heat to cook with, and light to read by. And we shall be able to carry this equipment in a satchel smaller than the ordinary suitcase.

"When wireless is perfectly applied, the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly. We shall see and hear one another as though we were face to face, even though thousands of miles separate us. And the instruments through which these wonders will be achieved will be amazingly simple. They may be small enough to be carried about in the pocket."

Dr. Tesla, who has discovered the fundamental principles of wireless or radio, the high frequency phenomena and the cosmic ray, who has given us the Tesla Coil and Oscillation Transformer, the High Potential Vacuum Tube, the Telautomatic Art and other important inventions, is also the discoverer of the basic principle of modern electrical science — the rotating magnetic field — embodied in his induction motor and alternating system of power transmission, which upon its commercial introduction by Westinghouse, in 1888, completely revolutionized the industries of the world.

Dr. Tesla was born in the Lika mountain district of Jugoslavia. His father was a clergyman, his mother an inventor like her father. Before he was six, little Nikola displayed the family genius in a scheme he evolved for catching bull-frogs. But that didn't deter his parents from directing him toward the ministry.

"When I was nine," Dr. Tesla told me, "I used to build little turbines in a mountain stream on my father's land and drive with belts all sorts of machinery. I told my uncle, ‘Some day I am going to America and I will run a big wheel at Niagara Falls.' I had read about the Falls and they fascinated me. But my uncle refused to take me seriously. ‘You'll never see Niagara Falls,' he told me. But I did come to America, and thirty years later, I realized my idea."

Probably few other boyhood dreams have had such brilliant fulfillment. Dr. Tesla, at many points in his career, has proved the soundness of the old adage that "nothing is impossible."

"From the age of ten," Dr. Tesla continued his story, "I had been inventing all sorts of things, from elementary devices to means for getting power from the planets, and my mind worked so fast that it was impossible to fix my thoughts on paper."

"Were we to seize and eliminate from our industrial world the results of Dr. Tesla's work," says Dr. B. A. Behrend, outstanding engineer and author, "the wheels of industry would cease to turn, our electric cars and trains would stop, our towns would be dark, our mills would be dead and idle."

At the gymnasium the young inventor became intensely interested in physics and electricity. But his parents still planned for him to become a minister. And he might have done so had it not been for a serious illness. After graduating from the Higher Realschule at Carlstadt in Croatia, he was stricken with cholera. Death seemed imminent. When his grief-stricken father tried to encourage him, he said:

"Perhaps I might get well, if you would let me become an engineer instead of a clergyman."

His father promised solemnly to send him to the best technical institution in the world if he would only recover.

"That promise," Dr. Tesla told me, "literally put new life into me. I did recover. And father kept his word. I was soon enrolled in the Polytechnic School in Gratz, Styria, one of the oldest institutions in Europe.

"During my second year there, we received a Gramme dynamo from Paris — a machine with a horseshoe form of field magnet and a wire-wound armature with a commutator, that has long since become antiquated. While the professor was demonstrating with the electro-dynamic principle the brushes sparked badly, and I suggested that it might be possible to operate a motor without those appliances. The professor declared that I could never create such a machine because the idea was equivalent to a perpetual motion scheme.

"When wireless is perfectly applied, the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly. We shall see and hear one another as though we were face to face, though thousands of miles separate us. . . ."

"Hearing this from such a high authority, I cast my idea aside for the time being. But it wouldn't leave my mind and before long I began thinking intently on the problem, trying to visualize the kind of machine I wanted to build and constructing all its parts in my imagination. These images were as clear and distinct as those I conjured up to drive away tormenting visions in my childhood, about which I am going to tell you presently. But it was not until four years later, in Budapest, that I arrived at a workable plan. One afternoon, I was walking through the City Park with a friend, and reciting poetry. The setting sun reminded me of these lines from Goethe's Faust:

The glow retreats, done is the day of toil;

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring;

Ah, that no wing can lift me from the soil,

Upon its tracks to follow, follow soaring!

"As I spoke those beautiful words, the vision of my induction motor suddenly appeared before my eyes, complete, perfect, workable. Like a flash it had come and I stopped quick to draw the vision in the sand. There I made the same diagrams I was to show six years later before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. The vision was so real that I cried with joy: ‘Look! Watch me reverse my motor!' And I did it, demonstrating with my stick.

"The day is not far distant when the human race will no longer be forced to labor for a livelihood. Then, we shall be judged as rich or poor according to our spiritual capacity and our will to do, rather than by our material possessions. High ideals alone will free us from the fetters of materialism."

"This discovery is known as the ‘rotating magnetic field.' It is the principle on which my induction motor operates. In this invention I produced a sort of magnetic cyclone which grips the rotable part and whirls it — exactly what my professor had said could never be done. After inventing this motor, I gave myself up more intensely than ever to the enjoyment of picturing in my mind new kinds of machines. And, in less than two months, I had created mentally nearly all the types of motors and modifications of the system which is now identified with my name.

"In 1888, shortly after my arrival in America, where I worked nearly a year with Thomas A. Edison, Westinghouse began the manufacture of my induction motor. And before long my system was universally adopted against tremendous opposition and skepticism. This system gave the first great impetus to the harnessing of water power, and was used with real success at Niagara Falls. It is now employed in the generation and transmission of power in practically every part of the world."

With his invention of the wireless light, Dr. Tesla achieved fame overnight. And since that time his name has grown continuously. Before he was forty, Lord Kelvin said of him, that he had contributed more than any other man to the study of electricity. That statement holds good today. C. A. Dana, the famous editor of the New York Sun said of him, "Men like Nikola Tesla can be counted on the fingers of one hand, perhaps on the thumb of one hand!"

Besides being one of the greatest living scientists, Dr. Tesla is a psychological phenomenon. His case has attracted the attention of the world's leading psychologists. Many of them have declared his methods of work to be unique. To explain these methods, it is necessary to go back once more to his childhood days.

"In my early years," Dr. Tesla told me, "l was greatly oppressed by the appearance of images of objects I had seen. These images were so vivid that they often blotted out my vision of real objects, and, by their persistence interfered with thought. Sometimes they were accompanied by strong flashes of light. Frequently, because of them, I passed through veritable agonies of fear. For instance, after I had seen a funeral, I no sooner retired to my room than the coffin appeared beside me and, no matter how I tried, I could not banish the image. For years I suffered so much from this that my life was almost despaired of.

"One day in my twelfth year, I was walking among the fields and feeling exceptionally well, when suddenly the object of a thought appeared before me. I thrust forth my hand to banish it. It receded. So thrilled was I by this victory of my will that I ran home, crying:

"‘Mother, I now can think of a thing without seeing it.'

"My mother laughed and said:

"You foolish boy, anybody can do that!'

"But I knew better. It had taken a great amount of will power for me to do it just that once.

"In trying to rid myself permanently of those tormenting visions, I began to take mental excursions beyond the small world of my actual knowledge. Day and night, in my imagination, I would journey through distant lands, meet and come to know strange people, grow very fond of them, and visit them again in later dreams, just as old friends. I can think of no greater enjoyment than that I derived from such experiences.

"Finally, I gained control of myself and became observant. And it was not long before I found that there was an external cause prompting every thought and action. In years of constant effort, I got so that I could not think of anything without becoming conscious of the impression which prompted the thought. Through this habit of locating the external cause that gave rise to a certain thought or action, I arrived at the conclusion that I was just an automatic engine, endowed with power of movement and motivated by impulses from the environment.

"In fact, we all are automata obeying external influences, entirely under the control of agents that beat on our senses from all directions of the outside world. Being merely receivers, it is a very important question how good the receivers are — some are sensitive and respond accurately. Others are sluggish and their reception is imperfect. The individual who is a better machine has so much greater chance of preserving himself and achieving success and happiness.

"Through my efforts to drive away those annoying images of my early years, I acquired a great facility for visualizing. And through this faculty I have evolved what is, I believe, a unique method of materializing inventive ideas and conceptions. This method may prove of great assistance to any imaginative man, whether he is an inventor, a business man, or an artist. It should help him to arrive at a clear conception of the central idea of his problem, instead of getting lost in the details.

"In brief, it is as follows: After experiencing a desire to invent a particular thing, I go on for days or months or even years with the idea in the back of my head. Whenever I feel like it, I play around with the problem without giving it any deliberate consideration. This is a period of incubation.

"Then follows the period of direct effort. I study the possible solutions of the problem and gradually center my mind on a narrowed field of investigation. When I am thus deliberately thinking of the problem in its specific aspects, I may begin to feel that I am arriving at the solution. And when I do feel that way, I know I really have solved the problem. That feeling is as convincing as the actual solution. In fact, I believe that the solution is then in my subconscious mind, although it may take a long time before it reaches the level of consciousness.

"As the form of the device becomes clearer, I change its construction, make improvements, and even operate it — all in my mind. If I am planning a machine of five hundred parts, I take the vital part, calculate all the dimensions from it, and give the workmen the accurate size of every detail. All of this is done without making a single sketch on paper, and when completed, the various parts fit together, just as certainly as though I had made accurate drawings. When the machine itself is finished, I slip my imaginary machine over it, as you would put a glove on your hand, and find that they coincide in the minutest detail.

"In ways, my method of work is an advantage. In others, it is a disadvantage. When you imagine things too easily, you are apt to neglect very important steps in practical life. You are likely to procrastinate, letting your work go until the last minute and then doing it in a hurry. The gift is fortunate only in so far as you use it to originate. But it also has helped me in other ways.

"Oftentimes, when I was a poor, young student without the money to buy an evening meal, I would retire to my room and visualize a sumptuous