Nikola Tesla Articles

Alternate Currents of High Potential and High Frequency - II

In operating an induction coil with these rapidly alternating currents, it is astonishing to note, for the first time, the great importance of the relation of capacity, self-induction, and frequency as regards the general result. The combination of these elements produces many curious effects. For instance, two metal plates are connected to the terminals and set at a small distance, so that an arc is formed between them. This are prevents a strong current to flow through the coil. If the arc be interrupted by the interposition of a glass plate, the capacity of the condenser obtained counteracts the self-induction, and a stronger current is made to pass. The effects of capacity are the most striking, for in these experiments, since the self-induction, and frequency both are high, the critical capacity is very small, and need be but slightly varied to produce a very considerable change. The experimenter brings his body in contact with the terminals of the secondary of the coil, or attaches to one or both terminals insulated bodies of very small bulk, such as exhausted bulbs, and he produces a considerable rise or fall of potential on the secondary, and greatly affects the flow of the current through the primary coil.

In many of the phenomena observed, the presence of the air, or, generally speaking, of a medium of a gaseous nature (using this term not to imply specific properties, but as contradistinction to homogeneity or perfect continuity) plays an important part, as it allows energy to be dissipated by molecular impact or bombardment. The action is thus explained: —

When an insulated body connected to a terminal of the coil is suddenly charged to a high potential, it acts inductively upon the surrounding air, or whatever gaseous medium there might be. The molecules or atoms which are near it are, of course, more attracted, and move through a greater distance than the further ones. When the nearest molecules strike the body they are repelled, and collisions occur at all distances within the inductive distances. It is now clear that, if the potential be steady, but little loss of energy can be caused in this way, for the molecules which are nearest to the body having had an additional charge imparted to them by contact, and not attracted until they have parted, if not with all, at least with most of the additional charge, which can be accomplished only after a great many collisions. This is inferred from the fact that with a steady potential there is but little loss in dry air. When the potential, instead of being steady, is alternating, the conditions are entirely different. In this case a rhythmical bombardment occurs, no matter whether the molecules after coming in contact with the body lose the imparted charge or not, and, what is more, if the charge is not lost, the impacts are only the more violent. Still, if the frequency of the impulses be very small, the loss caused by the impacts and collisions would not be serious unless the potential were excessive. But when extremely high frequencies and more or less high potentials are used, the loss may be very great. The total energy lost per unit of time is proportionate to the product of the number of impacts per second, or the frequency and the energy lost in each impact. But the energy of an impact must be proportionate to the square of the electric density of the body, on the assumption that the charge imparted to the molecule is proportionate to that density. It is concluded from this that the total energy lost must be proportionate to the product of the frequency and the square of the electric density; but this law needs experimental confirmation. Assuming the preceding considerations to be true, then, by rapidly alternating the potential of a body immersed in an insulating gaseous medium, any amount of energy may be dissipated into space. Most of that energy, then, is not dissipated in the form of long ether waves, propagated to considerable distance, as is thought most generally, but is consumed in impact and collisional losses — that is, heat vibrations — on the surface and in the vicinity of the body. To reduce the dissipation it is necessary to work with a small electric density — the smaller the higher the frequency.

The behavior of a gaseous medium under such rapid alternations of potential makes it appear plausible that electrostatic disturbances of the earth, produced by cosmic events, may have great influence upon the meteorological conditions, When such disturbances occur, both the frequency of the vibrations of the charge and the potential are in all probability excessive, and the energy converted into heat may be considerable. Since the density must be unevenly distributed, either in consequence of the irregularity of the earth's surface, or on account of the condition of the atmosphere in various places, the effect produced would accordingly vary from place to place. Considerable variations in the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere may in this manner be caused at any point of the surface of the earth. The variations may be gradual or very sudden, according to the nature of the original disturbance, and may produce rain and storms, or locally modify the weather in any way.

From many experiences gathered in the course of these investigations it appears certain that in lightning discharges the air is an element of importance. For instance, during a storm a stream may form on a nail or pointed projection of a building. If lightning strikes somewhere in the neighborhood, the harmless static discharge may, in consequence of the oscillations set up, assume the character of a high frequency streamer, and the nail or projection may be brought to a high temperature by the violent impact of the air molecules. Thus, it is thought, a building may be set on fire without the lightning striking it. In like manner small metallic objects may be fused and volatilized — as frequently occurs in lightning discharges — merely because they are surrounded by air. Were they immersed in a practically continuous medium, such as oil, they would probably be safe, as the energy would have to spend itself elsewhere.

An instructive experiment having a bearing on this subject is the following: — A glass tube of an inch or so in diameter and several inches long is taken, and a platinum wire sealed into it, the wire running through the centre of the tube from end to end. The tube is exhausted to a moderate degree. If a steady current is passed through the wire it is heated uniformly in all parts and the gas in the tube is of no consequence. But if high frequency discharges are directed through the wire, it is heated more on the ends than in the middle portion, and if the frequency, or rate of charge, is high enough, the wire might as well be cut in the middle as not, for most of the heating on the ends is due to the rarefied gas. Here the gas might only act as a conductor of no impedance, diverting the current from the wire as the impedance of the latter is enormously increased, and merely heating the ends of the wire by reason of their resistance to the passage of the discharge. But it is not at all necessary that the gas in the tube should be conducting; it might be at an extremely low pressure, still the ends of the wire would be heated; as, however, is ascertained by experience, only the two ends would in such case not be electrically connected through the gaseous medium. Now what with these frequencies and potentials occurs in an exhausted tube, occurs in the lightning discharge at ordinary pressure.

From the facility with which any amount of energy may be carried off through a gas, it is concluded that the best way to render harmless a lightning discharge is to afford it in some way a passage through a volume of gas.

The recognition of some of the above facts has a bearing upon far-reaching scientific investigations in which extremely high frequencies and potentials are used. In such cases the air is an important factor to be considered. So, for instance, if two wires are attached to the terminals of the coil, and streamers issue from them, there is dissipation of energy in the form of heat and light, and the wires behave like a condenser of larger capacity. If the wires be immersed in oil, the dissipation of energy is prevented, or at least reduced, and the apparent capacity is diminished. The action of the air would seem to make it very difficult to tell, from the measured or computed capacity of a condenser in which the air is acted upon, its actual capacity or vibration period, especially if the condenser is of very small surface and is charged to a very high potential. As many important results are dependent upon the correctness of the estimation of the vibration period, this subject demands the most careful scrutiny of other investigators.

In Leyden jars the loss due to the presence of air is comparatively small, principally on account of the great surface of the coatings and the small external action, but if there are streamers on the top, the loss may be considerable, and the period of vibration is affected. In a resonator, the density is small, but the frequency is extreme, and may introduce a considerable error. It appears certain, at any rate, that the periods of vibration of a charged body in a gaseous and in a continuous medium, such as oil, are different, on account of the action of the former, as explained.

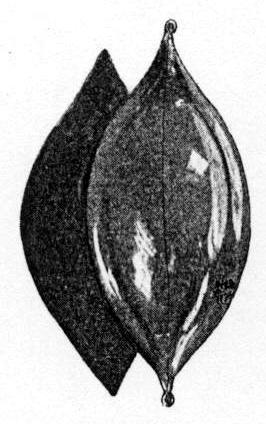

Another fact recognized, which is of some consequence, is, that in similar investigations the general considerations of static screening are not applicable when a gaseous medium is present. This is evident from the following experiment: A short and wide glass tube is taken and covered with a substantial coating of bronze, barely allowing the light to shine a little through. The tube is highly exhausted and suspended on a metallic clasp from the end of a wire. When the wire is connected with one of the terminals of the coil, the gas inside of the tube is lighted in spite of the metal coating. Here the metal evidently does not screen the gas inside as it ought to, even if it be very thin and poorly conducting. Yet, in a condition of rest, the metal coating, however thin, screens the inside perfectly.