Nikola Tesla Articles

Edison's Rontgen Rays Experiments

BY EDWIN J. HOUSTON AND A. E. KENNELLY.

Mr. Thomas A. Edison, after numerous experiments on the Röntgen rays with about 150 different glass vacuum tubes, has communicated the following information to us for publication:

First. There is no apparent advantage in obtaining a very high vacuum in the Crookes tubes employed for obtaining shadowgraphs of metal gratings. The effect of a very high vacuum is to require a greater voltage to produce fluorescence. The best degree of vacuum seems to be that at which the internal luminescence or stria in the tube just disappear and fluorescence of the walls remains. The Röntgen rays are still produced even when internal striæ are observed, but are then much enfeebled.

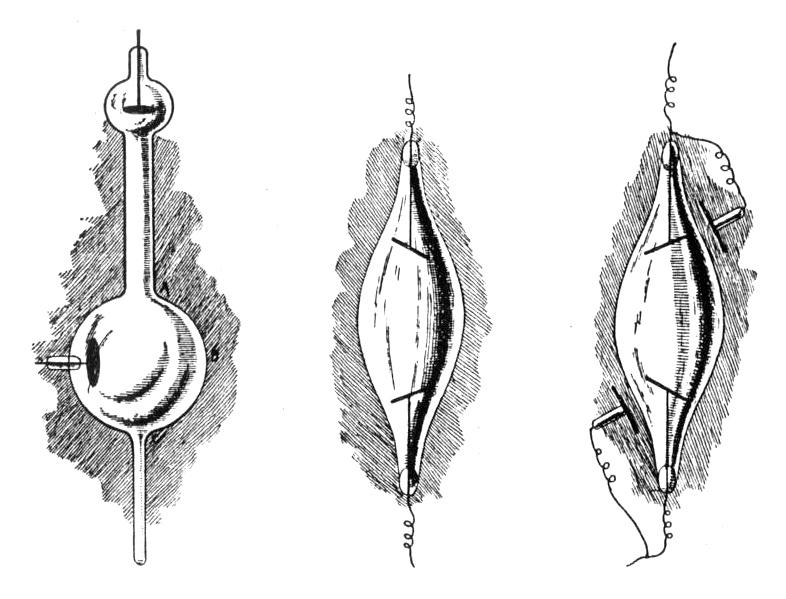

Second. Thin walls are preferable to thick walls in the glass vacuum tubes. A thick wall will fluoresce more noticeably and become very hot. A thin wall will emit rays upon the photographic plate, but may scarcely fluoresce visibly and will remain very cool. This is proved by a number of experiments, of which the following is one: The tube of a shape roughly indicated in Fig. I has its walls blown thick in the zone of A C, but thin at B. When this tube is exhausted and excited, the thin part, B, which is in the most active area, remains cool and the radiographic power is active, while the glass becomes hot in the ring A C. If B be made thick and A C thin, the glass at B may become melted by the heat, but its effect on a photographic plate is reduced, although its visible fluorescence is greater. Walls one eighth of an inch thick become unmanageable by excessive heating and rapid melting.

Third. For any given tube in a given condition of exhaustion, the radiographic power of the tube, i. e., the swiftness with which is produced a developable image, is roughly proportional to the square of the fluorescent candle-power or total visible fluorescent light given out by the tube.

Fourth. The duration of exposure has been found to be as follows: With the most sensitive plates in an ordinary plate-holder having a vulcanized fibre light-tight cover of about of an inch in thickness, the time necessary for obtaining a good radiograph of a metal grating or grid is less than one second, when the tube is within 4 of an inch of the grating and about 8" from the sensitive plate. At two feet distance, the time for an equally good radiograph is approximately 150 seconds, and at three feet, 450 seconds. For rough purposes the duration of exposure may be reckoned as proportional to the square of the distance.

Fifth: Of the photographic plates as ordinarily employed for photographic purposes, the medium rapid plates appear to be the most suitable for Röntgen rays; 2. e., to require less duration of exposure. Rapid plates and slow plates appear to be equally unfavorable in regard to sensitiveness for Röntgen rays as compared with medium plates. To test this, a composite sensitive plate was made from five strips cut from plates of different photographic sensitiveness, and a radiograph of a series of metal bars was taken, with the bars at right angles to the strips of the composite plate. For the same exposure and same development, the definition of the radiograph produced did not bear any apparent relation to the photographic sensibilities of the strips according to their sensitometer numbers. The medium rapid plate gave, however, much the densest image in every such experiment.

Sixth: The power of a tube having a given degree of exhaustion and disposition of electrodes increases with the surface area of its fluorescent walls; thus, a large vacuum tube exposing a large total fluorescent surface has a more rapid action on the sensitive plate; i. e., requires less exposure, but will require more voltage and more electric power to excite. On the other hand, for a given distance of the tube from the plate, the image is sharper and less distorted as the tube diminishes in size. Consequently, for a given tube used without a diaphragm, long distance and long exposure produce the sharpest radiograph. A small tube will produce a sharp image at a lesser distance, and for rapid exposures a very small tube at a very short distance is the best. The smallest tubes experimented with have been about one inch in diameter, with about two inches between electrodes, and with thin glass walls. A small tube requires a small E. M. F., so that tubes can be made to suit almost any induction coil.

Seventh. For a given thickness of glass wall, German glass appears to give better results than lead glass. The German glass employed gives a yellowish fluorescence, while lead glass gives a greenish fluorescence. These glasses phosphoresce visibly for at least ten minutes after the cessation of the discharge through the tube. A particular quality of Scotch boiler water-gauge glass used gives apparently equally good radiographic results, but does not appreciably phosphoresce after the cessation of the current. The residual phosphorescence has not yet been found to produce a visible photographic image. All phosphorescence yet observed is pale white, whatever the color of the preceding fluorescence under excitation.

Eighth. The form of the tube arrived at by a gradual process of selection is shown in Fig. 2. The length is about three times the diameter. This tube is made in various sizes. When the glass walls are thin for producing the best radiographic effect, a spark is apt to pierce the wall and destroy the vacuum. Partly on this account, tinfoil caps are placed over the extremities of the tube, as indicated by the shaded areas in the sketch. These tinfoil caps are in connection with the electrodes, and are cemented to the external surface of the tube by shellac.

Ninth. It was found in numerous trials with many tubes that the fluorescent and radiographic power of all the tubes without caps was greatly increased, roughly doubled, in fact, by bringing two metallic discs, connected with the respective electrodes, to the opposite points, represented in Fig. 3. The supposition is that the tube thus becomes at once an ordinary and electrodeless tube combined. The metal caps above mentioned were the outcome of these experiments, and not only have all these capped tubes remained unperforated, but their fluorescent and radiographic powers have been enhanced by the caps. The caps serve three purposes: (a) To stop piercing by permitting excessive sparking to escape over the external surface. (b) To increase the radiographic and fluorescent power. (c) To prevent undue heating of the internal electrodes, and a consequent charge of vacuum.

Tenth. The exciting apparatus consists of a large Ruhmkorff coil capable of giving a 12-inch spark, although such a length of spark is rarely required. The coil is excited either from a storage battery through an interrupter, or preferably from a 120-volt continuous-current circuit, through a bank of from 8 to 20 16-cp incandescent lamps arranged in parallel, with a rapidly rotating wheel-interrupter driven by a small motor. About 400 interruptions are made per second, and the duration of closure in the circuit is twice that of opening. An air-blast is directed upon the spark over the periphery of the interrupting wheel through a fine nozzle. This tends to produce a sudden breaking of the circuit. It has been found that greatly improved results have followed the removal of the usual condenser and the substitution of the air-blast. The resulting secondary E. M. F. is almost symmetrical, like an alternating E. M. F., and the two electrodes are apparently equally active. The secondary terminals of the induction coil are led directly to the vacuum tube. If the air-blast is removed and the condenser substituted, the fluorescent and radiographic power of the tube is greatly diminished.

We believe that these observations of Mr. Edison cannot fail to be valuable to many practical workers with Röntgen rays. We hope to communicate further experimental results at some future time,