Nikola Tesla Articles

Ein neues System von Wechselstrommotoren und Transformatoren von Nikola Tesla

(Translated from German)

In a lecture held on May 16 of this year before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Mr. Nikola Tesla reports on a new system of alternating current motors and transformers invented by him, essentially as follows:

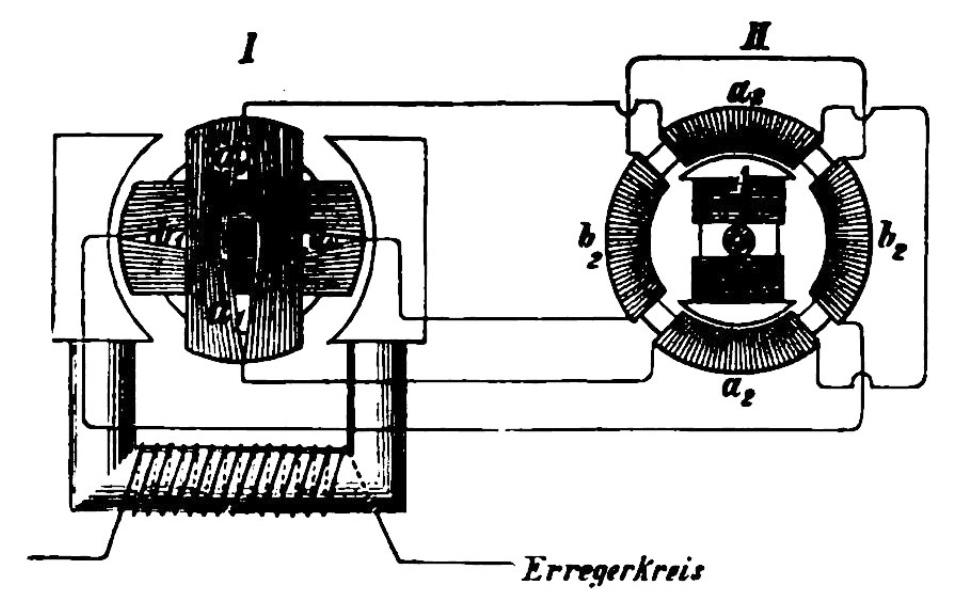

In the usual transmission of power by direct current, alternating currents are always generated in the armature wires of the primary machine, which must first be combined into a direct current upon their transition into the line and then split back into individual current impulses upon their entry into the secondary machine. The basic idea of Tesla's system now consists in omitting this double commutation. Imagine two direct current armatures I and II in the figure—which, for this purpose, as Mr. Tesla shows, only need two sections wound perpendicular to each other—and the ends of homologous sections a1 a1 connected with a2 a2 and b1 b1 with b2 b2 by lines. If armature I is now allowed to rotate in a magnetic field, the current waves that arise in its windings always pass through homologous windings of the secondary armature II simultaneously and produce in it a single magnetic axis, which rotates at the same speed as the primary armature while its intensity remains constant.

On this principle, Mr. Tesla bases two types of motors: the "synchronous" and the "asynchronous." Namely, he places inside the secondary armature—which in this case, as in the figure, must have a ring shape—a diametrically arranged iron core A mounted in the geometric axis of the ring, approximately in the form of a double-T armature. This armature will naturally strive to assume the position in which it captures the most lines of force, i.e., it will seek to follow the rotating magnetic axis of the ring and, left to itself, will after some time enter into a rotation synchronous with the primary armature. If this armature were provided with a winding excited by direct current, such a motor would, as long as synchronism prevails, be an exact reversal of an ordinary direct current motor. If the winding of the double-T armature is short-circuited within itself, according to Mr. Tesla, this facilitates starting, in that the currents arising in this short-circuited winding, as long as synchronism has not yet been achieved, have the tendency to delay the entry of the maximum magnetization in the double-T armature. As soon as synchronism is established, the armature winding naturally remains indifferent.

Mr. Tesla now utilizes this temporal shift of the maximum magnetization in the second type of his motor, whose performance is intended to be independent of the ratio of the speeds of the primary and secondary machines: The double-T armature is replaced by a drum armature, all of whose coils are short-circuited within themselves. If this armature is now braked in such a way that its speed is smaller by a constant amount than that of the magnetic axis of the secondary ring, one can imagine the latter as stationary but the armature as rotating with the difference of the two speeds, and it follows that current waves are induced in the self-contained coils of the inner, movable armature, which strive to shift the respective position of the induced magnetic axis of the inner movable armature by a constant angle against the direction of rotation. Thus, the intensity of the interacting poles is not increased by the short-circuited coils—as one might be led to assume by Mr. Tesla's wording—but rather the effective poles obtain, at the expense of their intensity, a position in which their mutual attraction is capable of producing a greater effect.

Such a motor is said to behave exactly like a direct current motor, to deliver an equally good efficiency under suitable load, and moreover to possess the advantageous property that it can never exceed a certain predetermined speed. Unfortunately, Mr. Tesla refrains from all numerical data on performance, efficiency, and expenditure in volt-amperes; however, some things can be noted a priori: Apart from the fact that Mr. Tesla needs four primary lines, or at least three as he states, his motor differs from an ordinary direct current motor in that, first, a constant work loss through remagnetization must occur in both the stationary and rotating parts—furthermore, the driving force is only the attraction of an electromagnet on soft iron, instead of, as in the direct current motor, the attraction of electromagnet on electromagnet.

Finally, regarding the use of Tesla's rotating magnetic axis for the transformation of high-tension currents, which he briefly discusses at the end of his lecture, his hopes for improving efficiency may nevertheless fail because he is forced to work with free magnetism. Nevertheless, his invention must be described as extremely ingenious, and the future may teach whether this new system will be able to take up the struggle for existence against the long-established ones.