Nikola Tesla Articles

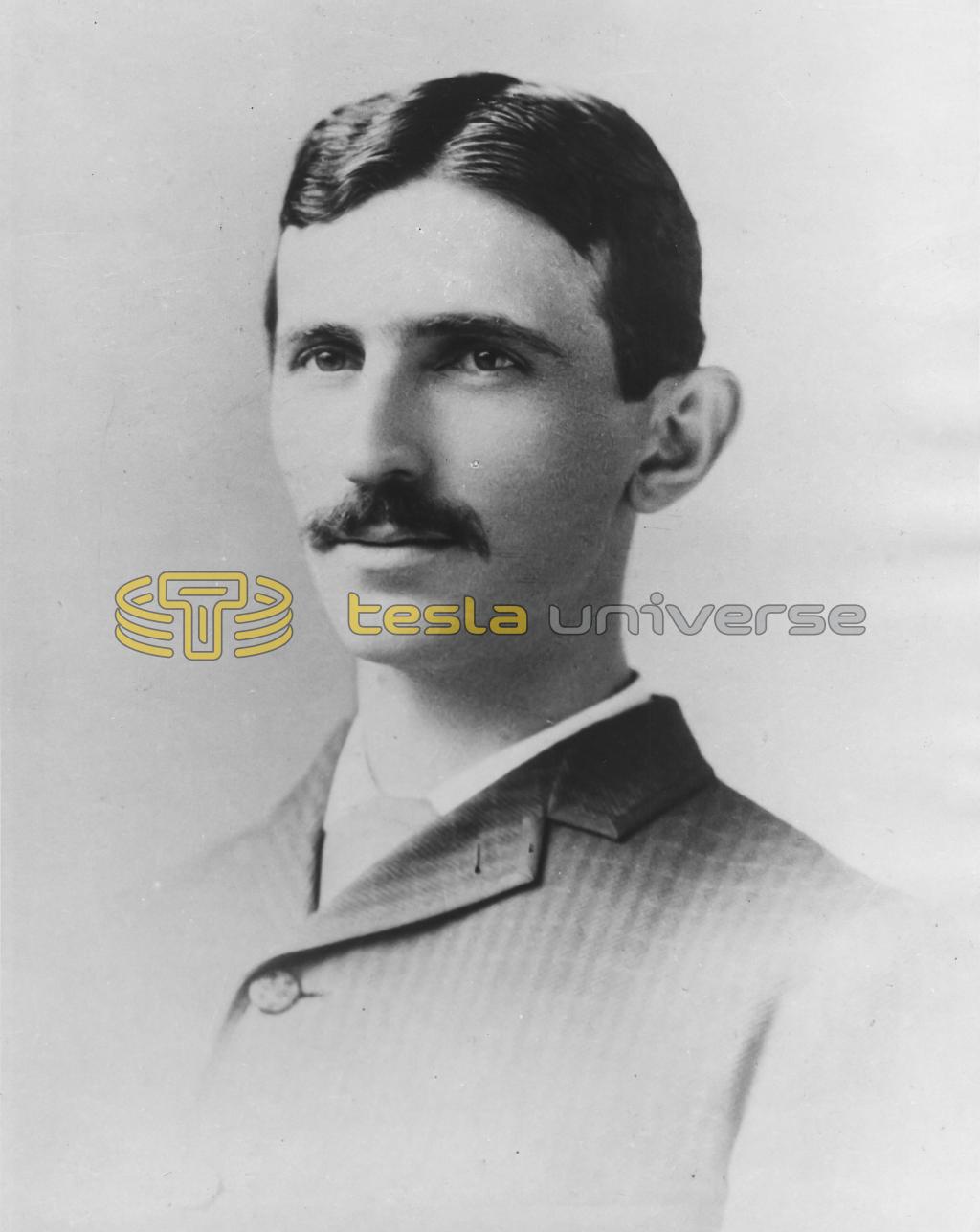

Electrical World Portraits - Nikola Tesla

While a large portion of the European family has been surging westward during the last three or four hundred years, settling the vast continents of America, another, but smaller, portion has been doing frontier work in the Old World, protecting the rear by beating back the "unspeakable Turk" and reclaiming gradually the fair lands that endure the curse of Mohammedan rule. For a long-time the Slav people - who, after the battle of Kosovopolje, in which the Turks defeated the Servians, retired to the confines of the present Montenegro, Dalmatia, Herzegovina and Bosnia and "Borderland" of Austria - knew what it was to deal, as our Western pioneers did, with foes ceaselessly fretting against their frontier; and the races of these countries through their strenuous struggle against the armies of the Crescent, have developed notable qualities of bravery and sagacity, while maintaining a patriotism and independence unsurpassed in any other nation.

It was in this interesting border region and from among these valiant Eastern folk that Nikola Tesla was born; and the fact that he, to-day, finds himself in America and is one of our foremost electricians is striking evidence of the extraordinary attractiveness alike of electrical pursuits and of the country where electricity enjoys its widest application.

Mr. Tesla's native place was Smiljan, Lika, where his father was an eloquent clergyman of the Greek Church, in which, by the way, his family is still prominently represented. His mother enjoyed great fame throughout the country-side for her skill and originality in needlework, and doubtless transmitted her ingenuity to Nikola; though it naturally took another and more masculine direction.

The boy was early put to his books, and upon his father's removal to Gospic he spent four years in the public school, and, later, three years in the Real School, as it is called. His escapades were such as most quickwitted boys go through, although he varied the programme on one occasion by getting imprisoned in a remote mountain chapel, rarely visited for service; and on another occasion by falling headlong into a huge kettle of boiling milk, just drawn from the paternal herds. A third curious episode was that connected with his efforts to fly; when, attempting to navigate the air with the aid of an old umbrella, he had, as might be expected, a very bad fall, and was laid up for six weeks.

About this period he began to take delight in arithmetic and physics. One queer notion he had was to work out everything by three or the powers of three. He would also calculate the cubes of every article of food put on the table at meals, and when in the streets would count every pace. He was now sent to an aunt at Carlstatt, Croatia, to finish his studies in what is known as the Higher Real School. It was there that, coming from rural fastnesses, he saw a steam engine for the first time, with a pleasure that he remembers to this day. At Carlstatt he was so diligent as to compress the four years course in three, and graduated in 1873. Returning home during an epidemic of cholera, he was stricken down by the disease, and suffered so seriously from the consequences that his studies were interrupted for fully two years. But the time was not wasted, for he had become passionately fond of experimenting, and, as much as his means and leisure permitted, devoted his energies to electrical study and investigation. Up to this period it had been his father's intention to make a priest of him, and the idea hung over the young physicist like a very sword of Damocles. Finally he prevailed upon his worthy but reluctant sire to send him to Gratz, in Austria, to finish his studies at the Polytechnic School, and to prepare for work as professor of mathematics and physics. At Gratz he saw and operated a Gramme machine for the first time, and was so struck with the objections to the use of commutators and brushes that he made up his mind there and then to remedy that defect in dynamo-electric machines. In the second year of his course he abandoned the intention of becoming a teacher and took up the engineering curriculum. After three years of absence he returned home, sadly, to see his father die; but, having resolved to settle down in Austria, and recognizing the value of linguistic acquirements, he went to Prague and then to Buda-Pesth, with the view of mastering the languages he deemed necessary. Up to this time he had never realized the enormous sacrifices that his parents had made in promoting his education, but he now began to feel the pinch, and to grow unfamiliar with the image of Francis Joseph the First. There was considerable lag between his dispatches and the corresponding remittances from home; and when the mathematical expression for the value of the lag assumed the shape of an eight laid fiat on its back, Mr. Tesla became a very fair example of high thinking and plain living; but he made up his mind to the struggle, and determined to go through depending solely on his own resources. Not desiring the fame of a faster, he cast about for a livelihood, and through the help of friends he secured a berth as assistant in the engineering department of the government telegraphs. The salary was five dollars a week. This brought him into direct contact with practical electrical work and ideas, but it is needless to say that his means did not admit of much experimenting. By the time he had extracted several hundred thousand square and cube roots for the public benefit, the limitations, financial and otherwise, of the position had become painfully apparent, and he concluded that the best thing to do was to make a valuable invention. He proceeded at once to make inventions, but their value was visible only to the eye of faith, and they brought no grist to the mill. Just at this time the telephone made its appearance in Hungary, and the success of that great invention determined his career, hopeless as the profession had thus far seemed to him. He associated himself at once with telephonic work, and made various telephonic inventions, including an operative repeater; but it did not take him long to discover that, being so remote from the scenes of electrical activity, he was apt to spend time on aims and results already reached by others, and to lose touch. Longing for new opportunities and anxious for the development of which he felt himself possible, if once he could place himself within the genial and direct influences of the gulf streams of electrical thought, he broke away from the ties and traditions of the past, and in 1881 made his way to Paris. Arrived in that city, the ardent young Likan obtained employment as an electrical engineer with one of the largest electric lighting companies.

The next year he went to Strasburg to install a plant, and on returning to Paris sought to carry out a number of ideas that had now ripened into inventions. About this time, however, the remarkable progress of America in electrical industry attracted his attention, and, once again staking everything on a single throw, he crossed the Atlantic.

Mr. Tesla buckled down to work as soon as he landed on these shores, put his best thought and skill into it, and soon saw openings for his talent. In a short while a proposition was made to him to start his own company, and, accepting the terms, he at once worked up a practical system of arc lighting, as well as a potential method of dynamo regulation, which in one form is now known as the "third brush regulation." He also devised a thermomagnetic motor and other kindred devices, about which little has yet been published, owing to legal complications. Early in 1887 the Tesla Electric Company of New York was formed, and not long after that Mr. Tesla produced his admirable and epoch-marking motors for alternating current, in which, going back to his ideas of long ago, he evolved machines having neither commutator nor brushes. It will be remembered that about the time that Mr. Tesla brought his motors out and read his thoughtful paper before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Prof. Ferraris, in Europe, published his discovery of principles analogous to those enunciated by Mr. Tesla. We may, therefore, mention the fact, as additional evidence of Mr. Tesla's priority in this field, that some months before Mr. Tesla read his paper we were cognizant of his new work, and that we had ourselves the pleasure of seeing his motors in successful operation several weeks before that memorable meeting in May at which his paper was read. His inventions, however, we believe, far antedate even that period.

Mr. Tesla's work in this field was wonderfully timely, and its worth was promptly appreciated in various quarters. The Tesla patents were acquired by the Westinghouse interests, and at the present time the Tesla alternating current motor is being applied by the Westinghouse Electric Company to work of different kinds. A week or two ago we illustrated its use in mining, and its employment in printing, ventilation, etc., has already been shown in our columns.

The immense stimulus that the announcement of Mr. Tesla's work gave to the study of alternating current motors would in itself be enough to stamp him as a leader; but from what we know of him, we do not hesitate to predict that this is not at all the only work by which he will be known and remembered.

Mr. Tesla is only 33 years of age. He is tall and spare, with a clean-cut, thin, refined face, and eyes that recall all the stories one has read of keenness of vision and phenomenal ability to see through things. He is an omnivorous reader, who never forgets; and he possesses the peculiar facility in languages that enables the educated native of eastern Europe to talk and write in at least half a dozen tongues. A more congenial companion cannot be desired for the hours when one "pours out heart affluence in discursive talk," and when the conversation, dealing at first with things near at hand and next to us, reaches out and rises to the greater questions of life, and duty, and destiny.