Nikola Tesla Articles

Oscillatory Currents and Some of Their Phenomena - I

Intense interest has of late been aroused in the many striking phenomena connected with oscillatory currents. This interest was first awakened among professional electricians and physicists by the extraordinary experiments of Hertz, later the general public became excited over the fairy-like effects obtained by Tesla, with his currents of high potential and high frequency, and now comes the production of the X-rays, which have forced a large body of scientists, the doctors and surgeons, to give their attention to electrical matters. Marconi's wireless telegraphy, an outgrowth of the experiments of Hertz and Lodge with oscillatory currents, is likewise exciting general attention. The interest felt in these matters is extended, but people's notions are in general vague as to the methods used for obtaining the effects, or the principles upon which they depend.

It is, however, surprising to note how many of the phenomena of oscillatory currents may be explained and connected by a right application of a very few simple physical principles with which everyone is instinctively acquainted. Furthermore many of the most interesting results may be obtained by any one who has a little ingenuity, clear physical conceptions, a few dollars and a room in which to experiment. It is feasible for every doctor using X-ray apparatus, and station-tender who has the disposal of alternating or direct currents, to rig up the necessary simple apparatus to repeat experiments along this line and to materially contribute to the general fund of knowledge upon the subject.

The writer will try and describe for the above class of readers of THE ELECTRICAL WORLD, in a simple non-mathematical manner and as far as possible non-technical form, the general methods and the construction of the necessary apparatus for obtaining oscillatory currents and their effects. He shall feel well repaid for his undertaking if doctors and others are induced to try for themselves some of the experiments to be described, and if they derive from their efforts a share of the delight which he felt when experimenting along the same line.

A clear physical conception of what constitutes an oscillatory current should be obtained before the attempt is made to describe what may be done with such currents. This may justify the somewhat lengthy description which follows:

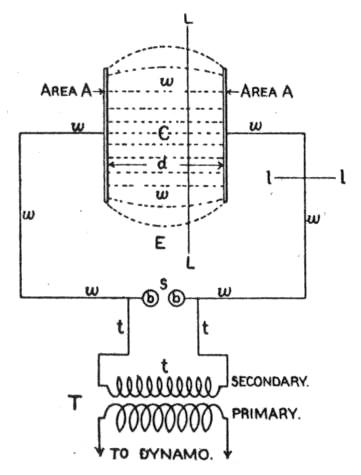

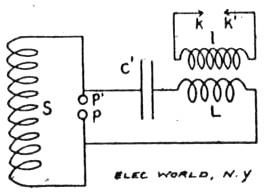

A common arrangement for obtaining an oscillatory current is diagrammatically illustrated in Fig. 1. Here C is a condenser, which may be considered as consisting of two square brass plates, having each an area A parallel and separated from each other by a distance d. T is a transformer, from the secondary of which a high-potential current, of 20,000 volts, say, may be obtained. b b are two metal balls, separated from each other about one-quarter inch. When a low-voltage slowly alternating current is sent through the primary of the transformer, the high voltage induced in the secondary of the transformer causes a discharge to pass across the air gap s, and an oscillatory current, that is, a current which, so to speak, swings back and forth in opposite directions like a pendulum, is found to exist in the circuit z (including the insulating space between the plates of the condenser). In the circuit t the current is slowly alternating, while in the circuit w the current is rapidly oscillating.

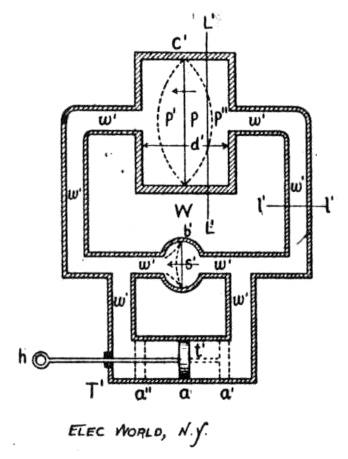

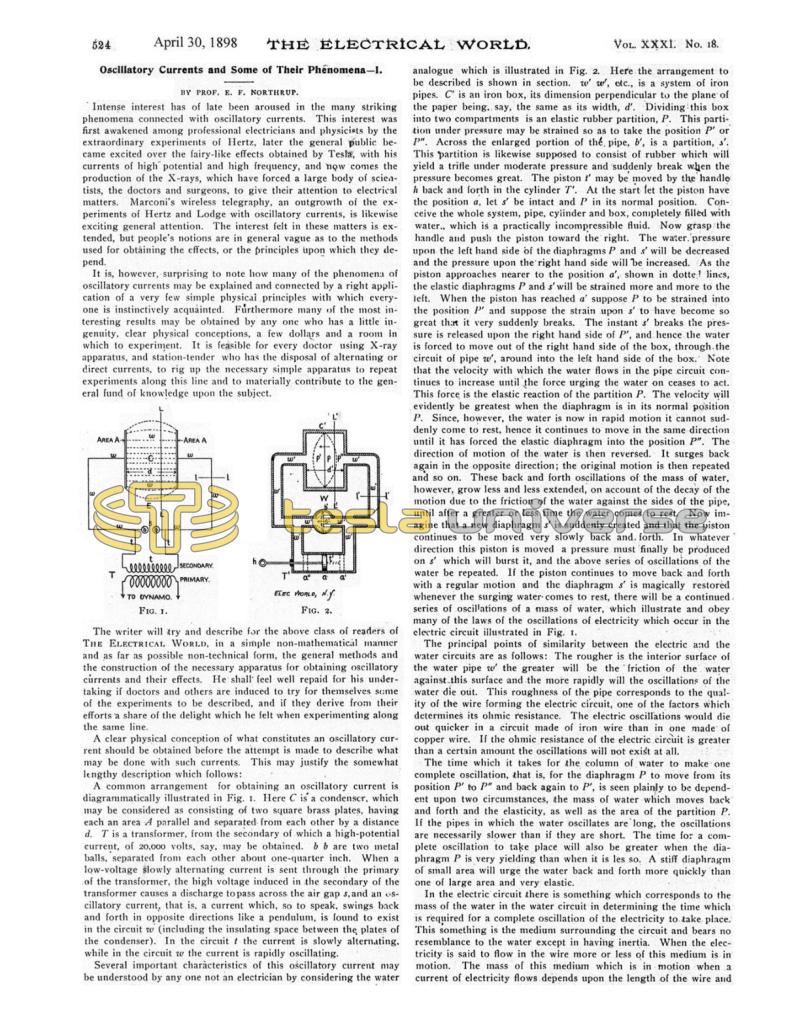

Several important characteristics of this oscillatory current may be understood by any one not an electrician by considering the water WORLD. analogue which is illustrated in Fig. 2. Here the arrangement to be described is shown in section. w' w', etc., is a system of iron pipes. C' is an iron box, its dimension perpendicular to the plane of the paper being, say, the same as its width, d'. Dividing this box into two compartments is an elastic rubber partition, P. This partition under pressure may be strained so as to take the position P' or P''. Across the enlarged portion of the pipe, b', is a partition, s'. This partition is likewise supposed to consist of rubber which will yield a trifle under moderate pressure and suddenly break when the pressure becomes great. The piston t' may be moved by the handle h back and forth in the cylinder T'. At the start let the piston have the position a, let s' be intact and P in its normal position. Conceive the whole system, pipe, cylinder and box, completely filled with water, which is a practically incompressible fluid. Now grasp the handle and push the piston toward the right. The water pressure upon the left hand side of the diaphragms P and s' will be decreased and the pressure upon the right hand side will be increased. As the piston approaches nearer to the position a', shown in dotted lines, the elastic diaphragms P and s' will be strained more and more to the left. When the piston has reached a' suppose P to be strained into the position P' and suppose the strain upon s' to have become so great that it very suddenly breaks. The instant s' breaks the pressure is released upon the right hand side of P', and hence the water is forced to move out of the right hand side of the box, through the circuit of pipe w', around into the left hand side of the box. Note that the velocity with which the water flows in the pipe circuit continues to increase until the force urging the water on ceases to act. This force is the elastic reaction of the partition P. The velocity will evidently be greatest when the diaphragm is in its normal position P. Since, however, the water is now in rapid motion it cannot suddenly come to rest, hence it continues to move in the same direction until it has forced the elastic diaphragm into the position P''. The direction of motion of the water is then reversed. It surges back again in the opposite direction; the original motion is then repeated and so on. These back and forth oscillations of the mass of water, however, grow less and less extended, on account of the decay of the motion due to the friction of the water against the sides of the pipe, until after a greater or less time the water comes to rest. Now imagine that a new diaphragm s' is suddenly created and that the piston continues to be moved very slowly back and, forth. In whatever direction this piston is moved a pressure must finally be produced on s' which will burst it, and the above series of oscillations of the water be repeated. If the piston continues to move back and forth with a regular motion and the diaphragm s' is magically restored whenever the surging water comes to rest, there will be a continued series of oscillations of a mass of water, which illustrate and obey many of the laws of the oscillations of electricity which occur in the electric circuit illustrated in Fig. 1.

The principal points of similarity between the electric and the water circuits are as follows: The rougher is the interior surface of the water pipe w' the greater will be the friction of the water against this surface and the more rapidly will the oscillations of the water die out. This roughness of the pipe corresponds to the quality of the wire forming the electric circuit, one of the factors which determines its ohmic resistance. The electric oscillations would die out quicker in a circuit made of iron wire than in one made of copper wire. If the ohmic resistance of the electric circuit is greater than a certain amount the oscillations will not exist at all.

The time which it takes for the column of water to make one complete oscillation, that is, for the diaphragm P to move from its position P' to P'' and back again to P', is seen plainly to be dependent upon two circumstances, the mass of water which moves back and forth and the elasticity, as well as the area of the partition P. If the pipes in which the water oscillates are long, the oscillations are necessarily slower than if they are short. The time for a complete oscillation to take place will also be greater when the diaphragm P is very yielding than when it is less so. A stiff diaphragm of small area will urge the water back and forth more quickly than one of large area and very elastic.

In the electric circuit there is something which corresponds to the mass of the water in the water circuit in determining the time which is required for a complete oscillation of the electricity to take place. This something is the medium surrounding the circuit and bears no resemblance to the water except in having inertia. When the electricity is said to flow in the wire more or less of this medium is in motion. The mass of this medium which is in motion when a current of electricity flows depends upon the length of the wire and the way in which it is coiled up, just as the mass of the water depends upon the length and diameter of the water pipe. The velocity of the motion of the medium is proportional to the strength of the electric current which is said to flow in the wire. This motion of the medium which surrounds the circuit is made manifest in the so-called lines of magnetic force. When a unit quantity of current sets in motion a certain mass of the medium surrounding the electric circuit, the circuit is said to have a certain inductance or coefficient of self induction. This inductance of the circuit then is represented in the water analogue by the mass of the water, and as the period of oscillation of the water is proportional to its mass, so the period of oscillation of the electricity is proportional to the self inductance of the electric circuit. The longer the wire and the more it is coiled up the greater this will be.

In the electric circuit just before the E. M. F. or force which urges electricity into motion becomes great enough to break down the thin air gap between the balls, this being represented by the partition s' in the water analogue, there is a strained condition of the medium between the two condenser plates. This is produced by the E. M. F. acting across the space between these plates just as the water-pressure force acts on the diaphragm P to strain it.

Now a particular thickness of medium or dielectric, as it is called, will be strained out of its normal condition by a certain E. M. F. by an amount which depends upon its nature, the same as a certain thickness of rubber diaphragm will be strained from its normal position under a given water pressure by an amount depending upon its flexibility. The amount of strain produced in both cases will be less the greater is the thickness of the substance strained. Evidently then the nearer the condenser plates are together the greater will the dielectric between the plates be strained or displaced and the greater will be the quantity of electricity which will have been moved across any imaginary plane, as L L. Likewise a greater quantity of water will move across any imaginary plane L' L' under a given pressure when the rubber partition is made more yielding. Note also the important fact that under a given pressure of the piston as large a quantity of water is forced across any imaginary plane l' l'as across any other imaginary plane, as L' L'. In the same way as large a quantity of electricity crosses one section of the circuit as any other. In short, as much electricity moves across the portion of the circuit which is made up of a so-called insulator as moves across any section of the conducting portion.

We may tabulate as follows the conditions which govern alike the oscillations in the water circuit and the electric circuit:

| ELECTRIC CIRCUIT. | |

| Roughness of interior of pipe. | Resistance of wire due to quality. |

| These determine the rate at which the oscillations die out. | |

| WATER CIRCUIT. | ELECTRIC CIRCUIT. |

| Mass of water in circuit. | Mass of medium in motion when current flows or self inductance of the circuit |

| Flexibility of diaphragm P. | Capacity of electric condenser. |

| These determine the time during which a complete oscillation occurs. | |

| WATER CIRCUIT. | ELECTRIC CIRCUIT. |

| Pressure which piston can produce. | E. M. F. of transformer. |

| Length of air gap S'. | Strength of partition S |

From the above comparisons it is seen that greatness of area of the condenser plates and their nearness together, or in electrical language, greatness of capacity, corresponds to greatness of elasticity and area of the rubber diaphragm, and hence the greater is the capacity of the electric condenser the slower will be the oscillations in the electric circuit. The sudden restorations supposed for the diaphragm s' are actually accomplished in the electric circuit by the inrush of cold non-conducting air as often as the oscillations in the circuit w have died out.

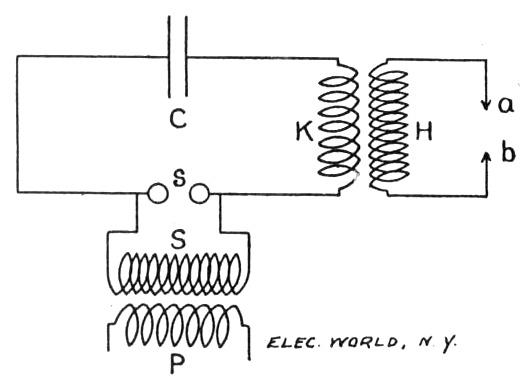

Let a circuit now be arranged as in Fig. 3. This circuit is supposed to be like that of Fig. 1 in all respects, except that at K the wire is wound into a coil or solenoid of eight or ten turns. Another coil of fine wire, H, is supposed to be wound around the coil K. When an oscillatory current now passes through the coil K a current is induced in the coil H. No known mechanical analogue can well illustrate or explain why a varying current of electricity in one circuit will induce or cause a current to flow in a neighboring circuit. Such, however, is the fact, the discovery of which added lustre to the already immortal name of Faraday. What concerns us here is that the force with which the electricity in the coil H is urged forward is, in the case illustrated above, very great. The high E. M. F. which is induced in the coil H is due to the very rapid rate at which its turns are cut by the magnetic lines which are produced by the oscillating current flowing in the coil K. When the circuit in the coil K has its maximum value there is a maximum number of lines of induction in the space about the two coils. When the condenser C is fully charged, and there is no current in the coil K then there are no lines of induction in the field. Now, if the two coils are wound so as to be close together and well insulated from each other, the lines of induction, which come into and go out of the field as the current in K rapidly changes its value and direction must all cut the turns of the coil H. These turns will be cut twice every time the current in the inducing circuit makes a swing in one direction; once as the current rises from zero to its maximum value and once as it again sinks to zero. Since the oscillations of the current take place with enormous rapidity, the turns of H are cut by the magnetic lines of induction with a like rapidity. It is an experimentally determined fact that the E. M. F. set up in a circuit which is being cut by lines of induction is proportional to the number of such lines per second which cut it, or as usually expressed, to the rate of change of induction through the circuit; hence in the circuit which includes the coil H the E. M. F. induced is very great. For example, the E. M. F. induced in H will be sufficient to produce an 8 or even a 10-inch discharge through air between the terminals a and b, when the circuits have approximately the following proportions: From the secondary S, of the transformer T, a sufficient E. M. F. must be obtained to discharge across the discharge gap s when a quarter of an inch long. The condenser C must have a capacity of about one two-hundredth of a microfarad, or a capacity such as would be obtained by stacking up about forty sheets of double thick window glass 10 by 10 inches and thirty-nine sheets of tin or copper. The coil K may have about ten turns of heavy wire and the coil H about 500 turns of fine wire. The current in H, of course, changes its direction with the same frequency as the current in K; that is, some millions of time in a second. The discharge from the coil H is what has been popularly called the Tesla current of high potential and high frequency. It may be remarked here, however, that phenomena of this class have been studied and developed in quite as able a manner by Prof. Elihu Thomson.

Before attempting to explain the effects, uses and practical methods of producing oscillatory currents it may be well to show diagrammatically the various arrangements of circuits which will give rise to such currents.

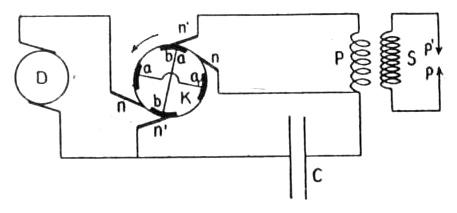

In Fig. 4 D is a direct current dynamo. The higher the voltage of this dynamo the better, for the effects to be described are increased in proportion to the square of the voltage; 500 volt machines used to operate electric street lines will give powerful effects. C is a condenser made of paper and tinfoil soaked in wax and having a very great capacity. P is a coil of a dozen or more turns, and S is a coil of several thousand turns. K is a device for alternating, allowing the condenser C to be charged by the dynamo, and for closing the circuit through the coil P, so the charged condenser can discharge through the coil. It operates as follows: a a and b b are strips of metal fastened on a cylinder of wood or hard rubber and cross-connected as shown. n' n' n n are four brushes which bear upon the cylinder, and have the relative positions shown in the diagram. It will be easily seen that if the cylinder is made to rapidly rotate in the direction of the arrow that when the brushes n n bear on two conducting pieces the condenser is in circuit with the dynamo and is being charged, and that the coil P is out of circuit, and that when the two brushes n' n' bear upon conducting pieces the condenser is in circuit with the coil P, and that it will then discharge through the coil, the dynamo then being out of circuit with the condenser. When, however, the condenser discharges an oscillation of electricity will take place through the coil P in the same way and for the same reason that it did in Fig. 1.

The oscillatory current in P will induce an oscillatory current of the same frequency in the coil S. If the coil S has many turns the current induced in it will be urged forward with a very high E. M. F., so that a long discharge may be obtained between the terminals p p'. Since, however, the condenser C, for reasons to be explained, must be made very large, the oscillations in the coil P will be very much slower than in the case of the circuit of Fig. 1, which is supposed to contain a condenser of small capacity, but charged to such a high degree or potential that it can discharge across an air gap.

Since the current swings slowly back and forth through the coil P, the rate at which the coil S is cut by lines of induction is not very great, and to obtain a high E. M. F. in the coil S this coil must have a great many turns of wire. This follows from the well-known principle that the E. M. F. set up in each turn by the inductive action is added to that set up in the other turns. The oscillatory current in the coil S, while having a very high potential, or in other words the power to discharge through a considerable length of air, oscillates with comparative slowness. To obtain an extremely rapid oscillation we may modify the circuit as illustrated in Fig. 5.

The terminals of the secondary coil Send in two balls, separated from each other about a quarter of an inch. A condenser of small capacity in series with a coil of a half dozen turns is joined to the opposite sides of the discharge gap p p'. If S then has potential enough to discharge across this gap an oscillatory current of very great frequency will flow in the coil L, which, by means of the coil l, can be raised or lowered in potential.

The condenser C, Fig. 4, must have a very large capacity, for the following reason: The quantity of electricity which any charged condenser contains is proportional to the potential to which it has been charged or to the force, so to speak, with which electricity was forced into it. Referring to Fig. 2 it is evident that the excess of water in the box on one side of the partition P over that on the other side will be proportional to the force exerted upon the handle h of the piston t'. Now this excess of water on one side of the partition P corresponds to the quantity of electricity in the condenser C of Fig. 1, and the force exerted upon the handle h to the potential or E. M. F. of the secondary of the transformer T which charges the condenser C. Such being the case, if the condenser C in Fig. 4 had a small capacity and was only charged by the low E. M. F. of the dynamo D, it would contain very little electricity, which, when discharged through the coils P, makes a rapid oscillation but produce a current having very little intensity. In short, the condenser C would have very little energy stored up in it, and however the relations of the two coils P and S are adjusted, only a small display of energy could be obtained from the terminals p p'. If we attempted to make the discharge between p p' long it would be found to be very thin, and if a condenser, C', were connected across its terminals the discharge would be very much shortened, if not eliminated altogether. It can be shown that the energy contained in any condenser is proportional to its capacity and to the square of the potential to which it is charged, so that when working with low potentials very large condensers must be used to obtain effects which exhibit much energy.