Nikola Tesla Articles

To Telegraph Around the Great World Without Wires

TO TELEGRAPH

Around the Great World

WITHOUT WIRES.

A New System Evolved Fraught with Immense Possibilities and Which Scientists Are Studying.

LABORS OF TESLA AND EDISON.

To girdle the earth with telegraphy without the use of telegraph wires has been the dream of many an electrical inventor. There is a fascination in the theory of harnessing those mysterious etheric streams of electricity which stratify the upper atmosphere, and harnessing them for the purpose of the world's enlightenment and civilization. But it has never been done.

Many an inventor has tried it and failed. Many an inventor has spent his life dreaming of potentialities without hitting upon the key to the secret. The whirling world generates electricity just like a dynamo. It is a sort of giant revolving battery, terrifically polarized, sparkling, streaming at one end with the aurora, which sends off its ribbons of magnetic currents in vast, flickering fingers, which girdle the earth with a power strong enough to run the world's engines, could it once be bridled and bitted and snaffled by man.

Scientists know the power is there, and they dream of it and reach for it with half blind eyes, and uncertain fingers, too weak to scratch the surface of the secret, and too dazed to do anything but grope for it.

As yet wireless telegraphy is in its infancy. It is an infancy that will grow, however, and one day in the coming century the infant may become a giant that will bowl the world down the ringing grooves of change, bound and swathed with a power that I will roll the blessed old ball to the foot of. God's throne — bloodless, stainless, warless, and with a record as white as the wings of the sinless angels who will then inhabit it.

At least, the scientists think so, and, why should I, a mere layman in scientific matters, contradict them? Telegraphing as it is at present is more or less of an annoyance compared with telephones — barring the central office; and if they can be improved so as to facilitate the transmission of general news, the sooner the problem is solved the better.

A Wonderful Invention.

The latest scientist to take a header into the sea of wireless telegraphy is a young man named Mr. Marconi, who has recently evolved a system of telegraphy without wires, which depends not on electro-magnetic but on electrostatic effects. That is to say, the new system is based on Hertzian waves, which have a vibration of not less than 270,000,000 a second.

Think of it! These Hertzian waves are to electricity what the X rays are to visual perception; but, unlike the X ray, they do not die out easily. They simply take hold of one end of an electric stream and shake it into waves so infinitesimally small and keen that it would take the ear of a fairy to hear the magnetic surf beating on the shores of cloudland.

These vibratiors are projected through apace in straight lines, but, like light, they are capable of reflection and refraction and of focusing, and right upon this fact the scientists have based their dreams of wireless telegraphy, With the fact that the Hertzian waves exhibit all the phenomena of light before then, the scientists have gone to work to construct instruments that will handle these waves, as heliographs handle the rays of the sun. They may succeed. It Is to be hoped they will. In the meantime, Mr. Marconi, Mr. Edison and Mr. Tesla will strive for the grand result that will enable them to drum upon the electric streams as a farmer drums upon a tin pan to hive a refractory swarm of bees.

In speaking of Mr. Marconi's invention in London recently, Mr. Preece, the telegraphic expert of the London Post Office. admitted that telegraphing without wires was no new thing. Probably Mr. Preece meant that inadvertent telegraphing by means of induction was no new thing. Here in the United States, in 1878, there were but two wires running from Kansas City to Denver. Many a time I have sat in the Denver office with the first wire idle, yet the instruments were responding to the messages, being sent on the second wire. And at no point in all that treeless waste of arid land between the two cities were the two wires nearer to each other than three or four feet.

It must have been this "induction" of dry and magnetic atmospheres that first gave scientific men the idea of telegraphing without wires. Mr. Preece, whom I have quoted above, says that in 1884 operators in the telephone exchange in London were able from sounds heard to read messages that were in transit from London to Bradford by the telegraph wires. The post office wires were under ground and the telephone wires above ground, and careful experiment showed that this fact accounted for the telegraphic messages to Bradford being read by the telephone company. Yet, all the same, it was a mere case of induction.

The invention of young Marconi seems to have dealt with the problem from an entirely different standpoint. It does not deal with the inducing of a current from a neighboring wire. In fact, induction has nothing to do with it. It is an electro-static wave question, and the only thing that now remains to be done is to ascertain the distance to which these telegraphic signals can be transmitted.

The great difference between the Marconi and the inductive methods of wireless telegraphy is that the former does away entirely with the wires at each end. Vibrations are set up by one apparatus and received by the other.

Tesla's Experiments.

On our side of the water wrestling with this very problem we have Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison. Tesla is more or less of a dreamer. Give him an idea and he will expand it to the stars if he sees possibilities in it. He is an inventive electrical poet, who takes hold of an idea, and with philosophy as a fulcrum tries to unlock the universe. Nevertheless he has worked out some astonishing problems, and is even now completing an invention with which he hopes to circle the globe with telegraphic sound without the aid of wires.

Fully ten years ago Tesla declared that it would be possible to use economically the electricity in the earth's atmosphere for communication between widely divergent points. The problem in his mind was the conservation of electrical energy at the least possible cost.

Long and wearily did Tesla puzzle his brain over this problem. He discarded the induction scheme almost immediately. Induction is more or less a matter of propinquity. Then he hit upon the scheme of oscillation. He went to work upon an oscillator, which was nothing less than an instrument to throw out and produce the enormously swift Hertzian waves.

Through this instrument he thought it possible to solve the problem of aerial telegraphy. In speaking of this possibility Tesla said: "In time the electric envelope of the earth will enable us to send messages from one part of the globe to all other parts in an instant."

This is a rather broad assertion, but there are those who believe as Tesla does, that the electrical elements of the earth and the atmosphere are infinite, and that it will be only a matter of time when these forces of nature are subjugated to the will of mankind.

Tesla also asserted that this electrical element of the earth's atmosphere might at some future time be utilized for communication with other planets of our system. Here is a dream indeed. Those who have suggested such communication in the past have expended their mental ingenuity on schemes for gigantic electric lettering on the world's deserts and plains.

This would be aerial telegraphing with a vengeance. But do not get nervous. Noth- ing of the kind will ever occur, unless some fool with a billion dollars to spare leases Sahara Desert for his interstellar electric plant. This is something of a digression, but let us follow it a bit further. Supposing such gigantic lettering were possible, and supposing that return signals were received, what would it prove?

Nothing more than an interchange of intelligence, surely. Nothing more would be possible. What would be the first word flashed across the abyss of space? "God," of course. And right here we would stall. No human ingenuity could go further than this, unless some strange comet should flare across the sky to hinge another word upon. Telegraphic communication along the currents of the earth's upper atmosphere may be possible, but interstellar talk is as far off as Byron's dream of darkness.

And yet Tesla believes great things of his oscillator, and, upon being asked once whether it would be possible to signal to the stars, replied:—

"Perhaps in time. Not yet. There are many things to be fixed first. I have no doubt that it would be possible to signal to the the stars."

Well, it may be so. If in the future it shall stand on the pale and ghost haunted hills of the moon, looking across soundless tracts of space to the red disk of the world, and shall hear a far cry tingling to the stars, a voice that walls through the waste lands like the cry of a lost soul, I shall know that it is Tesla, or Edison, or some terrestrial philosopher howling for the central office of the universe.

As for telegraphing around the earth without wires, ah! that is a different thing. We believe in Tesla and we believe in Edison. Give them an inch of success, and eventually they will make it a mile. Both have said that such a thing is possible, and both know what they are talking about.

As early as 1886 Edison made successful experiments in induction telegraphy from moving trains, sending and receiving telegrams on the Staten Island Rapid Transit road during almost an entire afternoon. The train from which Mr. Edison experimented consisted of five cars, with metal roofs, which were made continuous with pieces of insulated copper wire and connected in the rear car with an ordinary telegrapher's outfit. There was a leap of at least fifty feet from the train to the wires running beside the track, and the bankers and capitalists smiled when they saw the preparations. Very few of them believed that such a thing was possible.

Edison's Induction Scheme.

The train left Clifton at half-past one P. M., and before it had gone a quarter of a mile the instrument in the rear car was clicking merrily. An operator had been stationed at Clifton with a special set of instruments. To this operator the capitalists and others upon the train, had delivered many sealed messages.

Before Tottenville was reached all these messages had been received on the train, leaping through the fifty feet of space to the metal roofs of the cars and so to the telegraph instrument. On the return trip despatches were sent from the train to all parts of the country. One message was in Latin, but it got through the atmosphere all right.

Mr. Henry Seligman, the banker, telegraphed to his banking house for Lake Shore quotations and got an answer before the train stopped running. On this occasion Edison stated that a leap of six hundred feet was possible.

Edison began work in 1892 on a marine telegraph based upon the principle of induction. This invention was patented, and by it Mr. Edison was enabled to telegraph a goodly distance across water without the use of wires.

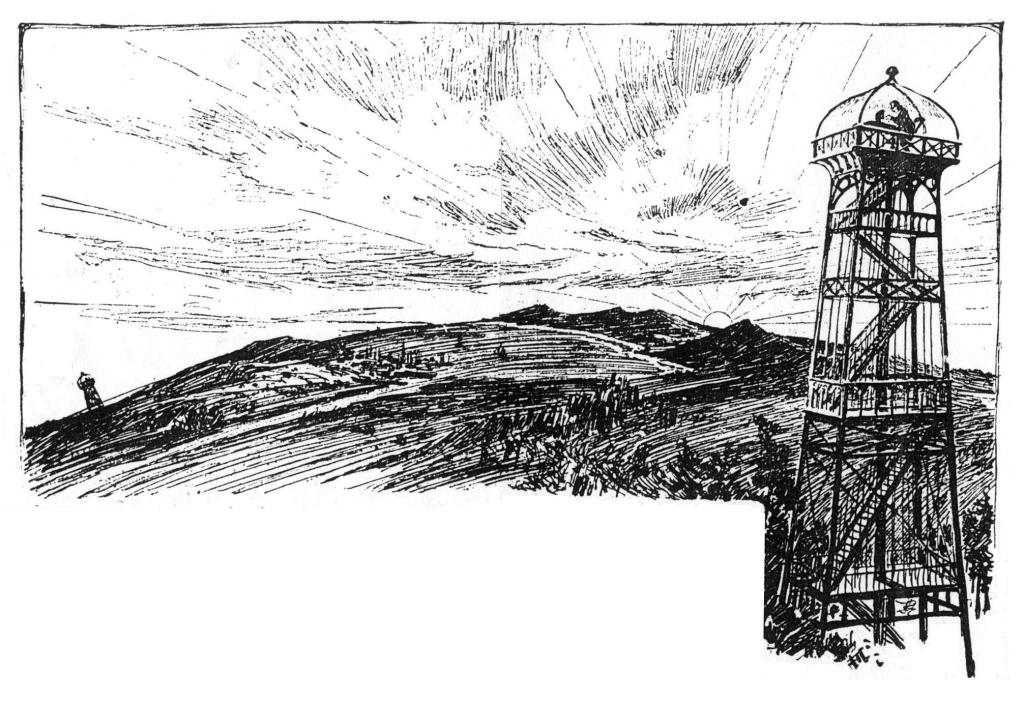

But the great difficulty with all these experiments, whether with induction or Hertzian waves, is that the waves will not follow the curvature of the earth's surface. In this respect they are related to the X rays, which, in fact, seem to be a sort of illuminated electricity.

The point to overcome in telegraphing long distances without wires is to obtain a sufficient elevation to overleap the curvature of the earth's surface, and to reduce to a minimum the earth's absorption of the electric current. "At sea," said Edison, in speaking of marine telegraphy, "from an elevation of one hundred feet I can communicate a great distance without wires, and by repeating these signals from ship to ship communication can be established across seas and oceans.

"Collisions in fogs can be prevented and ships approaching a dangerous coast can be assured of safety."

It would be rather a hard matter to obtain one hundred feet elevations at sea, but there are many mountain chains that would afford splendid opportunities for experiment. if not for practical use. In fact, Tesla has already telegraphed a goodly distance from one mountain peak to another without the use of wires.

Aerial Mountain Telegraphy.

If the terrific impulse of these Hertzian waves is not overestimated, a sort of mountain telegraph might be established from Washington Territory to Nicaragua, and, with a few towers, even to the lower part of Chill and Patagonia. From lofty Mount Everest the signals could be flashed, peak by peak, to Mount Hood, Ranier. Shasta, and so down that long continental vertebra of granite to Gray's Peak, Long's, Lincoln's, Pike's, the Holy Cross, La Veta, through the Sierra Madre to Popocata peti, Orizaba, into Nicaragua, across the Isthmus and into the cloud soaring Cordilleras.

Here the peaks would be higher and communication probably more clear and swift. Down the lofty line of snowy summits the news would click as swift as thought, from Chimborazo to Aconcagua, and along the snowy range into strange, dismal lands, and at last the Patagonian, crouching with a wondering face over his miserable fire with the despatch in his hands, would know that Casey had struck out.

This may be an exaggeration, but the fact remains that many scientists are so thoroughly convinced that the use of atmosphere and earth currents of electricity is practicable that they are working with might and main to bring about the desired end.

In a recent interview, Marconi, the man who has recently interested London on the subject of telegraphy without wires, said:—

"I have long believed that instantaneous and simultaneous communication to all parts of the earth is possible by means of electric waves. I am becoming more convinced every day that such communication can be based upon scientific principles which can be controlled at will.

"Those huge disturbances on the sun, which are nothing more nor less than waves of electricity, are productive of similar disturbances on the earth in the form of storms. Why should not disturbances of the electric currents of the earth's atmosphere be made intelligible? It is not necessary that a conducting circuit must exist.

"An electrical disturbance at one point causing a change in the equilibrium of the earth's electricity should be felt at all points of the earth's surface, and I think it possible to record them. The possibilities of such a transmission of intelligence cannot be exaggerated. A message sent from London would be in America, Africa and Australia in an instant."