Nikola Tesla Articles

Telegraphing Without Line Wires - I

It will be seen from the patents hereinafter cited that the present subject is not new. It has occupied the attention of inventors for at least fifty years; and, indeed, if we include signaling by flashlight or by sound, it will be found that for thousands of years man has been endeavoring to communicate to distant points without the intervention of artificial connecting media. It would, however, go beyond the limits of this article to mention all the experiments and applications of the various forms of signaling by light and other natural agents that have been tried for so many years. In view of the renewed interest in the subject that has been aroused by recent experiments of English and Continental physicists, who have used electrical methods for accomplishing the above result, and in view of the close relationship which exists in this country between the work of the theoretical scientist and the work of the practical inventor, it may be of interest to give a review of the electrical development of the patented art bearing on this form of signaling.

The electrical methods which have been used to transmit intelligence without intervening wires may be broadly divided into three distinct classes, i. e., conduction methods, in which battery currents are used and in which the earth serves as a conductor; methods in which the transmission is effected by induction, and electrical wave methods. Induction methods may be again subdivided into two classes, to wit: Electromagnetic and electrostatic methods.

CONDUCTION METHODS

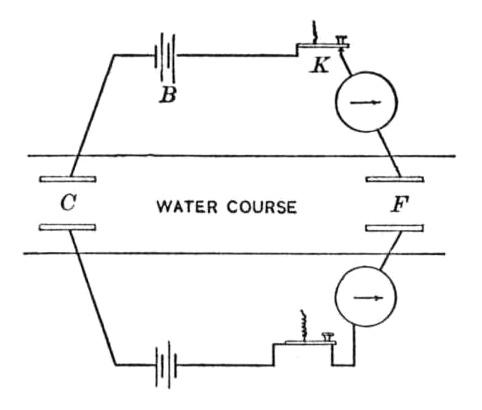

About the earliest patent in which the earth is used as a conductor to effect transmission is the English patent to Lindsay, No. 1242, of 1854. This patent contains all the essentials which enter into this means of telegraphing, and is open to all the objections that accompany this system. In it, as shown in Fig. 1, the patentee telegraphs across an intervening water course by using on one side of the water a battery, B, connected to two plates which are placed a considerable distance apart in the stream or lake. On the opposite side of the water course are placed two corresponding plates connected by wires which include a galvanometer and another battery. The patentee states that "the distance between the two plates on one side of the water course is greater than the distance across the water or to the plates of the opposite battery. Suitable keys, K, may be placed in the circuits. On closing the key in one circuit the electric current will pass into the water at C, through the wire or wires which are on the opposite side of the water, and re-cross at F; or, more correctly speaking, the electric current divides between the two courses in an inverse ratio to their resistances, so that a portion of it takes the circuitous course." It will, of course, be evident that the distance between the plates of one circuit may be diminished, if at the same time the e. m. f. of the battery connected to these plates be increased.

In the conduction system we are dealing with two plates buried in a conducting medium and kept at a suitable difference of potential. We may imagine the current distributed through the medium along certain stream lines, a fall of potential resulting along the different lines of flow. If the two ends of a receiving circuit be grounded at two points between which there is a sufficient difference of potential, enough current will be shunted through this circuit to actuate a recorder. An analogous case is afforded by the laboratory experiment, in which the lines of flow of the current from a battery are determined, when its poles are placed in contact with a sheet of tin foil. One end of a circuit which includes a galvanometer and a battery is touched to the sheet of foil, and the other end moved until a position is found for which the galvanometer gives no deflection. The former end of the circuit is then kept in its original fixed position on the tin foil, and the latter end moved until another point is found for which the galvanometer deflection is zero and so on. These points are then plotted and enough pairs of points found to locate the equipotential curves, which are normal to the lines of flow. It will be seen therefore that in the conduction system, the receiver might have its terminals so located that no current from the transmitter will be shunted through it and that the best position for the terminals of the receiving circuit is in a stream line of maximum intensity and at right angles to the equipotential curves. It will also be desirable to curve the end plates of the receiving circuit to fit the equipotential curves at the points where they are buried in the earth so that all the points of each plate may be at the same potential. This will avoid local circuits in the plates. Usually such curvature will be unnecessary, since the plates are small and the stream lines are straight at the points where the receiving terminals are located, and plane plates may consequently be substituted.

The objections to this method of transmission are many and obvious. Nowadays, when, in all large cities, currents from railway circuits and lighting systems are constantly leaking to earth, great disturbances of the instruments used in this system must be expected. Secrecy is impossible, since anyone may ground his instrument, and thus receive the signals intended for another. Only a small portion of the current generated by the battery will pass through the receiving instrument. This instrument must, therefore, be quite sensitive, which in turn may render it subject to the disturbances above referred to. The battery current, moreover, is short circuited by street-car rails, gas pipes and water pipes, so that very little current will reach the recorder.

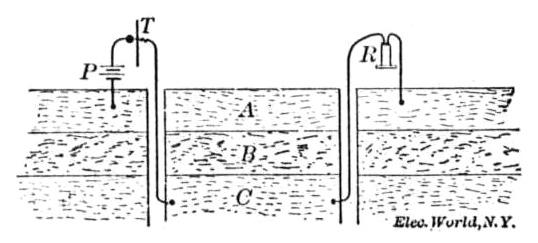

It is interesting to notice, however, that this particular method has been many times revived, even as late as 1894, when it appeared in "Cosmos," Paris, March 3, 1894, republished by the "Electrical Review," Vol. 24, p. 193, which described some experiments by the Abbé L. Michel, in which telephones were used as receiving and transmitting instruments. See Fig. 2. Five accumulators P were used in the transmitter circuit, and with the receiver R placed in a building about 3000 feet away, telegraphic dispatches were heard quite distinctly. In these experiments two distinct paths may be arranged for the electric current, according to the position of the plates in each circuit. If a plate is placed at the bottom of a well at C, and the other plate of the same circuit is placed in the surface soil A, and if there is an intervening layer B of high resistance soil between the transmitter plates, the plates of the receiving instrument R being similarly located, then the path of the current will be from one plate of the transmitter through the surface soil to the corresponding plate of the receiver, then through the receiving instrument and back by the bottom layer of earth. The intervening high resistance stratum will prevent short circuiting of each instrument. The other method would be to locate the plates of each instrument a suitable distance apart, but all of them in the surface soil, which is substantially the method of the English patent to Lindsay.

Between the dates of Lindsay's invention and the "Cosmos" article a number of patents have been taken out, all based on the principle of the resistances of branched circuits. Among them may be enumerated the following: In Great Britain - Haworth, No. 843, of 1862, and No. 2682, of 1863; Smith, No. 8159, of 1887; Stevenson, No. 5498, of 1892; Smith et al., No. 10,706, of 1892; and in the United States the following: Ader, No. 377,879, February 14, 1888; Blake, No. 526,609, September 25, 1894.

The Smith patents show a means of communicating from the shore to a lighthouse on an island by the use of submerged plates, one pair being connected to a receiving instrument in the lighthouse, and another pair arranged to include the former pair between them, the latter pair being connected by wires to a transmitting battery and key on the shore. In the last cited patent to Smith stepdown transformers are used to energize the plates located in the signaling circuit. These, of course, generate heavy currents, so that an appreciable part of them may flow through the receiving instrument in the lighthouse. It is evident that devices of the last-named character can transmit signals through a short distance only without intervening wires. The advantages that result from their use are due to the ability of dispensing with shore connections for the cables on rocky coasts where lighthouses are usually situated. In heavy gales the ordinary cable is often torn from its bed and communication between the shore and the lighthouse is interrupted. By burying one of the plates of a conduction system in the ocean sufficiently below the surface of the water to avoid the disturbing action of the waves on the signals, and its neighbor in a well on the lighthouse shore, the necessity of bringing a cable end on land is avoided, and a fairly satisfactory means of communication is established.

An application of this method to ship signaling seems to offer a chance of success, owing to the short distance between the ship and the signal transmitting circuit. In this connection the following patents may be cited, which illustrate a means of avoiding collisions of ships with each other, or of preventing them from running ashore: In Germany, Somzee, No. 44,101, of 1888; in Great Britain, Stevenson, No. 5498, of 1892, and in the United States, Blake, No. 526,609, September 25, 1894.

In Somzee's invention each ship carries a pair of plates submerged in the water, one at the bow, the other at the stern, the plates being connected by wires which include a signal-receiving instrument, such as a telephone or galvanometer. Shoals may be indicated by suitably energized stationary plates, the current from which is diverted into the receiving circuit on the ship whenever the vessel approaches shallow water. A similar method is used in the Stevenson and Blake patents. The conduction system of transmission is fully explained by Rathenau in a report to the General Electric Society in the "Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift," for November 8, 1894, in which it was suggested that a telephone receiver be used to receive the signals. The metallic diaphragm of the telephone was to be replaced by a light tongue, which should be tuned to respond to the predetermined rate of vibration of the transmitting circuit. This rate was to be imposed upon the circuit by a suitable tuning fork operating a circuit breaker. The investigator stated that communication had been effected over a distance of 3 miles.

INDUCTION METHODS

These methods have already been classified into electromagnetic and electrostatic systems. The difference between them is largely one of degree, inasmuch as in each both kinds of induction may play a part, although usually the effect of one preponderates over that of the other. The intimate relationship which exists between the two methods is explained by the modern theories of inductive action. Maxwell's theory assumes that an e. m. f. which acts upon a dielectric produces an electric displacement, and that the change in electric displacement is an electric current called the displacement current. This displacement current in dielectrics is accompanied by magnetic force. It originates a field of magnetic lines of induction which surround it just as a wire carrying a current is surrounded by lines of force. The converse propositions whereby displacement currents are created by the change in the intensity of a magnetic field readily follow from the original assumption.

According to the J. J. Thomson theory, both kinds of induction are produced by electrostatic tubes of force, called by him Faraday tubes, some of them open and some closed, which are distributed through the ether. Each open tube which starts from a positive charge of electricity terminates on an equal and opposite negative charge. This gives rise to the ordinary phenomenon of electrostatic induction. The phenomena of the electromagnetic field are due to the motion of the Faraday tubes, or to changes in their position or shape; if, for example, a moving tube cuts a closed conductor, a current is induced in it.

The differences in the two methods above referred to result from the relative importance of the induction coil and the condenser in the particular circuit under consideration. In electromagnetic induction methods the magnetic field of the circuit supplied by the induction coil is the important element, in the so-called electrostatic system the effects are due to the condenser which gives rise to the electrostatic field of force.

The term electrostatic induction, which has been freely used, seems to be a misnomer when applied to phenomena which are due to electricity in motion. The appearance and disappearance of the induction tubes which accompany the charge and discharge of a condenser give rise to the induced current, and the effect is not one of electrostatics but of electrokinetics. It would be more accurate therefore, to apply the term capacity or condenser methods to the class called electrostatic induction, and the phrase mutual-induction system to the electromagnetic-induction methods. The older terms have been retained for convenience.

ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION METHODS

About 1893 Mr. W. H. Preece gave a renewed impetus to the electromagnetic induction class by some experiments performed in England, in which the inductive method was exhaustively tried. In previous experiments by the same investigator in which buried plates were connected to two parallel wires a considerable distance apart, the effects were attributed largely to earth conduction, and it was necessary to prove that the action in the later trials was electromagnetic in its nature. This was unquestionably true in some of the experiments, but there is still some doubt as to the nature of the action in all the tests. One method was to use insulated copper wires in quarter-mile squares laid on a level plain, a quarter of a mile apart. Alternating currents were sent through the transmitting circuit, and these, when interrupted by means of a telegraph key, gave Morse signals which were received in suitable telephones. The data are given in full in the Proceedings of the Electrical Congress at the World's Fair for 1893, published by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

The electromagnetic induction method has been the subject of a number of patents, attention being called to the following: In the United States - Phelps, No. 307,984, Nov. 11, 1884; 312,506, Feb. 17, 1885; Woods, No. 373,915, Nov. 29, 1887; Ader, No. 377,879, Feb. 14, 1888. In England - Evershed, No. 10,161, of 1892; Sennett, No. 13,415, of 1892, and Evershed, No. 18,312, of 1896. In Germany the patent to Somzee above cited.

The patents to Phelps and to Woods furnish applications of the method of transmitting signals to or from a moving railway train. A coil of wire, including in its circuit a transmitting key and a receiving instrument, is located on the car so that the coil may pass in close proximity to a telegraph wire strung upon poles or on the roadbed. These devices necessitate the presence of a telegraph operator upon the car, and inasmuch as it is an easy matter to dispatch telegrams at the nearest stopping point which may be written out on the train, it will readily be seen why this system has not gone into extensive use.

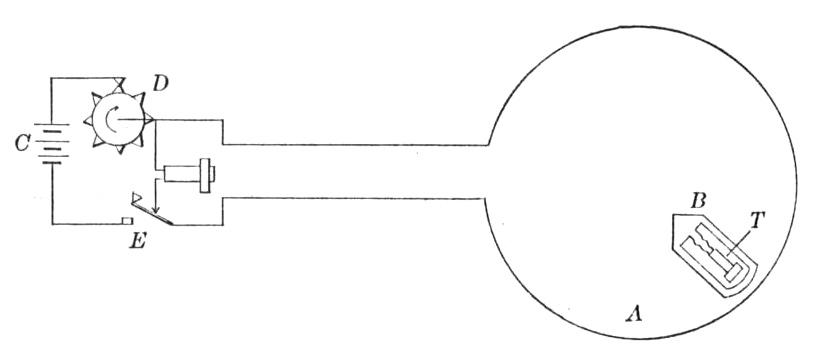

The English patents to Evershed and to Sennett above cited disclose methods of signaling from the shore to lightships or other vessels approaching the shore. An inductive circuit is arranged with a coil A, see Fig. 3, located in the ocean in a horizontal plane, the coil being supported, if desired, by suitable buoys so as to bring the magnetic field produced by the coil near the surface of the water below the vessel B which sails over it. The signaling circuit may be produced by an alternating-current dynamo, or by means of a battery C and revolving contact wheel D, which rapidly interrupts the battery current. A telegraph key E is used, by means of which signals of short and long duration are given according to the Morse or other code. The receiving instrument may be a telephone receiver T or an electromagnet acting on a reed of metal tuned to correspond in pitch to the frequency of the secondary currents. A call bell may be rung by means of a local battery in the circuit of a relay, the relay consisting of a tuning fork designed to respond to the timed impulses of the transmitting circuit.

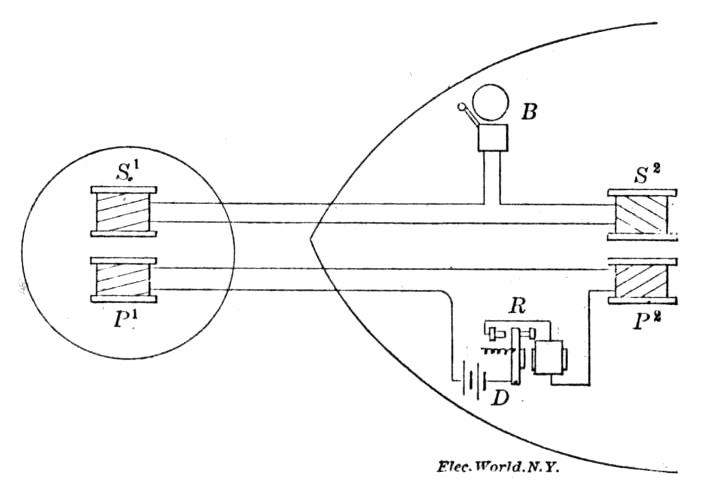

In the German patent to Somzee, which has been discussed above, a modification is used which adopts the principle of the Hughes induction balance. See Fig. 4. In this method the balance is formed by two circuits, each including a pair of coils, one circuit being completed through a battery D, and automatic circuit breaker R, and the other through a bell. One pair of coils P2 S2 is placed upon the ship, the other pair P1 S1 is located upon a float which is dragged by the ship. The inductive effect of P2 on S2 is normally balanced by that of P1 on S1. When the vessel approaches a shoal, which should be marked by means of a large metal buoy, the balance of the currents is destroyed by the metal of the buoy and the bell rings. The method employed by Somzee has been used by Huskisson in patent No. 542,732, July 16, 1895, for the automatic firing of mines located in a harbor. The induction balance is connected to the mine, and when the ship passes over it the current balance being destroyed by the inductive action of the metal of the ship, the mine is fired.

In the methods which have just been described the effects are due to mutual induction. The current flowing through the signaling circuit creates a magnetic field of force, the lines of which penetrate the receiving circuit. Any change in the intensity of the current produces a corresponding change of the field, and this gives rise to an induced current in the receiving circuit, whose e. m. f. is measured by the rate of decrease of magnetic induction through it. This gives the equation \(E = -M \frac{di}{dt}\)

in which E is the induced e. m. f. at any instant, M is the coefficient of mutual induction of the two circuits, and i is the current in the inducing circuit at any instant.

If, as in some of the cases discussed above, we have an alternate current flowing through the primary circuit whose equation is

i =I sin a

in which I is the maximum value of the primary current, we have for the value of the induced e. m. f.:

\(E = M I \cos a \frac{da}{dt}\)

The effective secondary induced e. m. f. is therefore:

E" = 2 !$ \pi !$ f M I'

in which I' is the effective primary current, f is the frequency of the primary current wave, and M is the coefficient of mutual induction.

It follows from this equation that in order to make this method of signaling as sensitive as possible we must use large currents of high frequency in the signaling circuit, as many turns of wire as possible in both circuits and increase the permeability of the intervening medium by introducing magnetic materials therein.

(To be Continued.)

* The classification adopted in this article has been followed by the patented art in its development, and is also that which has been used by Prof. S. P. Thompson in a review of the literature of the subject in the "Journal of the Society of Arts," London, April 1, 1898.