Nikola Tesla Articles

Telegraphing Without Line Wires - II

Electrostatic Induction Methods

The electrostatic system may be said to represent an intermediate stage in the development of the art of telegraphing without line wires. Some of the difficulties which are met and overcome in this method of signaling, e. g., the dampening effect of intervening obstacles, occur in the modern or Hertzian wave method. In some of the patents that used electrostatic induction for their effects electrical waves occur, but, as will appear more fully below, the wave effect is lost or inconsiderable. Some of the electrostatic methods have been used, a number of years ago, in railroad signaling, examples of which are furnished by the following patents: Smith, 247,127, September 13, 1881; Phelps, 334,188, January 12, 1886; Edison et al, 486,634, November 22, 1892.

The patent to Smith was the first to describe a means of signaling by induction to a moving railway train. The metallic roof of the car which should be insulated is connected to a wire which leads to one terminal of a telephone receiver, the other terminal of the receiver being grounded through the wheels and rails. A telegraph line is strung along the track in closer proximity to the car than is customary for Morse signaling. On telephoning over the line from a station on the road the car roof is affected inductively, and a current is produced in the receiver on the car, the line and the roof forming the two plates of a condenser. An advantage of this method of transmitting signals is that the line wire along the track may be used for telegraphing according to the ordinary Morse system, without disturbing the telephonic signals. The current induced in the car circuit in this patent is probably due to both electromagnetic and electrostatic induction.

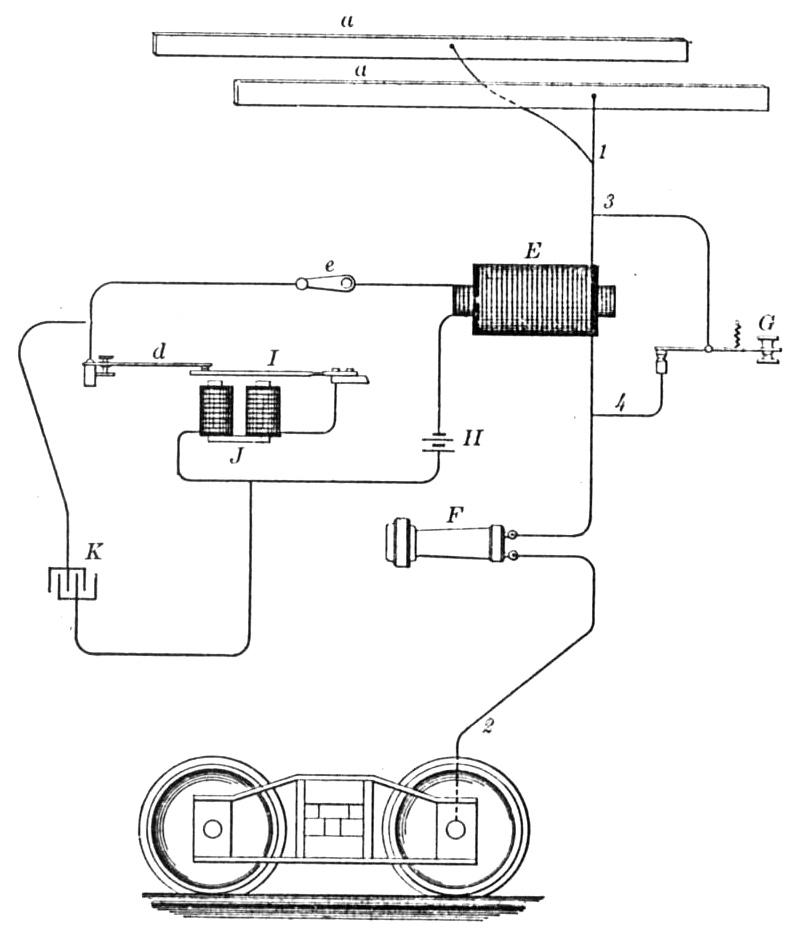

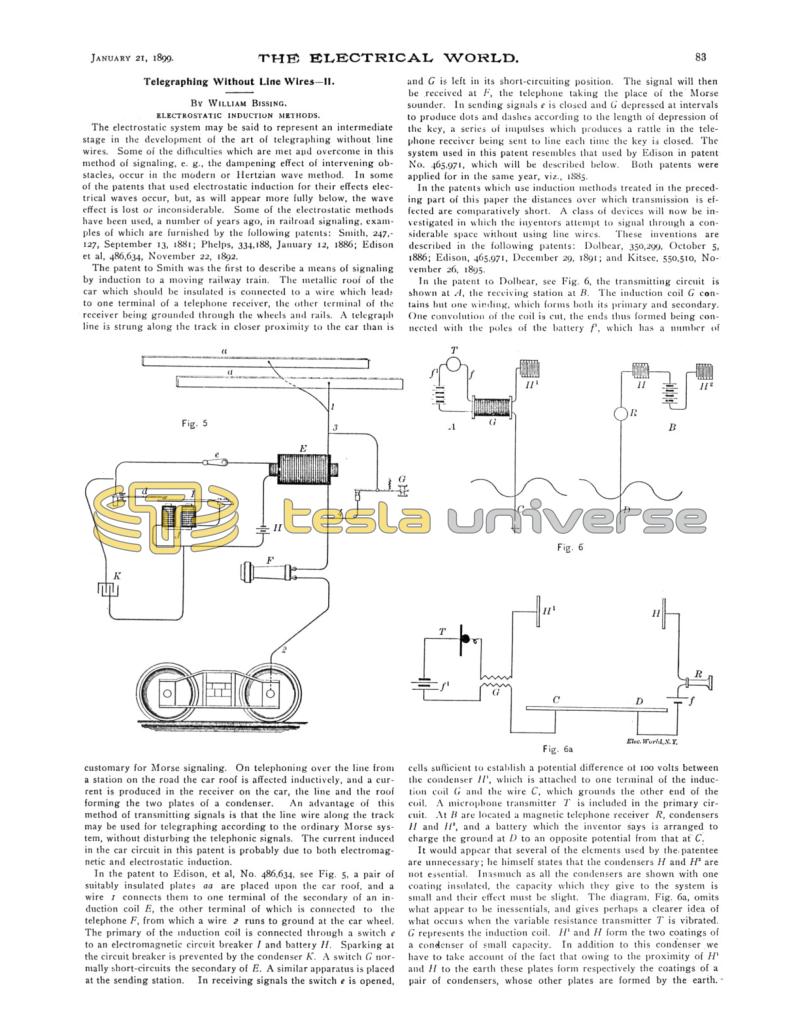

In the patent to Edison, et al, No. 486,634, see Fig. 5, a pair of suitably insulated plates aa are placed upon the car roof, and a wire I connects them to one terminal of the secondary of an induction coil E, the other terminal of which is connected to the telephone F, from which a wire 2 runs to ground at the car wheel. The primary of the induction coil is connected through a switch e to an electromagnetic circuit breaker I and battery H. Sparking at the circuit breaker is prevented by the condenser K. A switch G normally short-circuits the secondary of E. A similar apparatus is placed at the sending station. In receiving signals the switch e is opened, and G is left in its short-circuiting position. The signal will then be received at F, the telephone taking the place of the Morse sounder. In sending signals e is closed and G depressed at intervals to produce dots and dashes according to the length of depression of the key, a series of impulses which produces a rattle in the telephone receiver being sent to line each time the key is closed. The system used in this patent resembles that used by Edison in patent: No. 465,971, which will be described below. Both patents were applied for in the same year, viz., 1885.

In the patents which use induction methods treated in the preceding part of this paper the distances over which transmission is effected are comparatively short. A class of devices will now be investigated in which the inventors attempt to signal through a considerable space without using line wires. These inventions are described in the following patents: Dolbear, 350,299, October 5, 1886; Edison, 465,971, December 29, 1891; and Kitsee, 550,510, November 26, 1895.

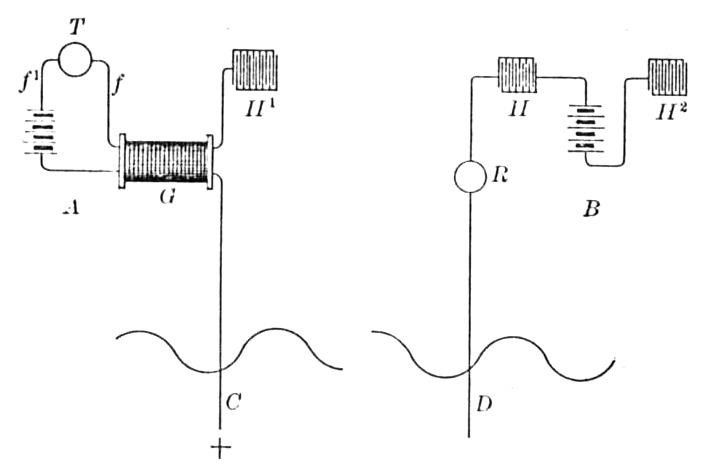

In the patent to Dolbear, see Fig. 6, the transmitting circuit is shown at A, the receiving station at B. The induction coil G contains but one winding, which forms both its primary and secondary. One convolution of the coil is cut, the ends thus formed being connected with the poles of the battery f1, which has a number of cells sufficient to establish a potential difference of 100 volts between the condenser H1, which is attached to one terminal of the induction coil G and the wire C, which grounds the other end of the coil. A microphone transmitter T is included in the primary circuit. At B are located a magnetic telephone receiver R, condensers H and H2, and a battery which the inventor says is arranged to charge the ground at D to an opposite potential from that at C.

It would appear that several of the elements used by the patentee are unnecessary; he himself states that the condensers H and H2 are not essential. Inasmuch as all the condensers are shown with one coating insulated, the capacity which they give to the system is small and their effect must be slight. The diagram, Fig. 6a, omits what appear to be inessentials, and gives perhaps a clearer idea of what occurs when the variable resistance transmitter T is vibrated. G represents the induction coil. H1 and H form the two coatings of a condenser of small capacity. In addition to this condenser we have to take account of the fact that owing to the proximity of H1 and H to the earth these plates form respectively the coatings of a pair of condensers, whose other plates are formed by the earth. The capacity of this last-named pair is considerably greater than that of the condenser H H1, for the capacity of a condenser varies inversely as the distance between the plates, and the distance from H or H1 to earth is much less than from H to H1. Consider now the circuit C G f1 T G H1H R D C, in which a variable e. m. f. is produced by the vibration of T. There will be two paths for the alternating current produced by the change in the variable resistance T; one circuit beginning at the battery f1 leads to the transmitter, then through one-half of the induction coil to H1 to earth at C, and returns through the other half of the induction coil to the battery; the other circuit goes from H1 to H, through the receiver R, and returns by way of the earth and through the path of the first circuit to H1. It is the latter circuit that transmits the signals from T to R. Knowing the resistance, self-induction and capacity of each of these circuits, the amount of the e. m. f. of the battery and the variation in the resistance of T, the strength of the current in each of the two branches may be calculated. It will be seen that only a small proportion of the current produced in the local circuit f1 T G H1 C f1 will be diverted into the receiving circuit at R. The battery at f, which is connected in series with the battery at f1, increases the total e. m. f. in the signaling circuit, so that by means of it a given change in the resistance T will increase the current through the receiver R.

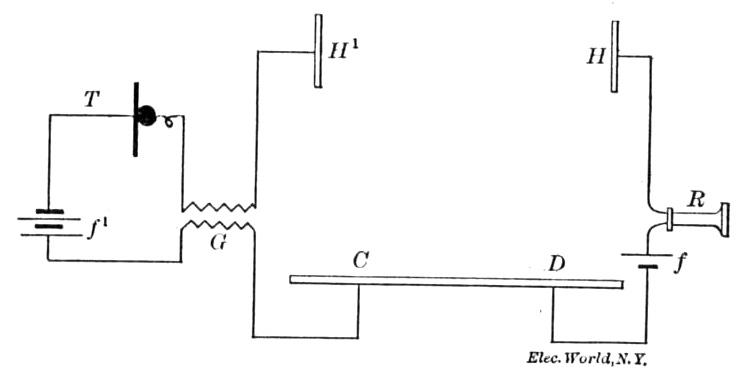

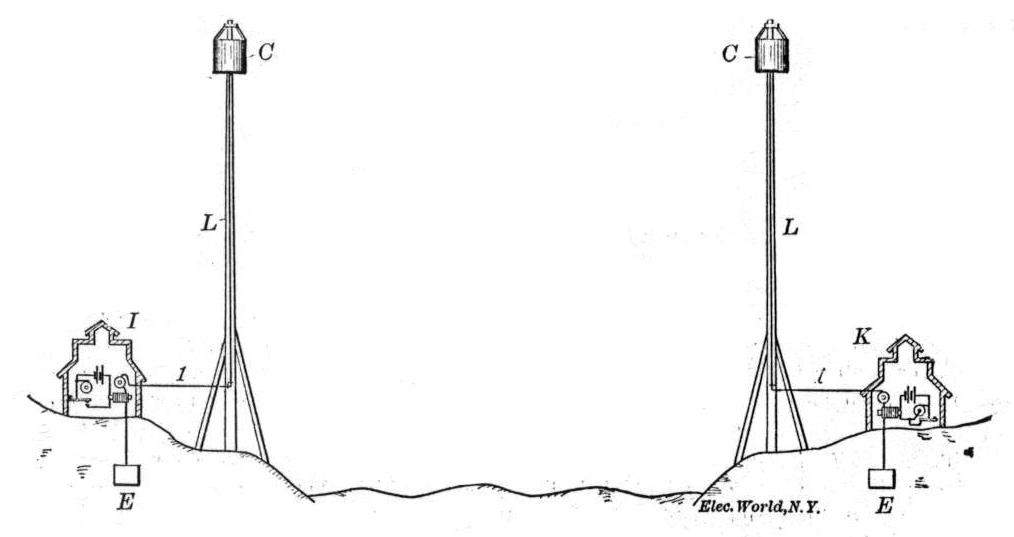

The apparatus used by Edison in his patent No. 465,971 is shown in Figs 7, 7a and 7b. In these figures two capacity areas C are placed at a suitable elevation and connected by wires I through his electromotograph receivers D and the secondary of the induction coil F to the earth. The electromotograph is a revolving chalk cylinder upon which a metal brush rests, giving a note of definite pitch (see patent No. 221,957 to Edison). When the current flows through the instrument the friction between the brush and cylinder changes, and this produces a note of different pitch. Any other form of receiver, which can be operated by alternate currents, may be substituted. A revolving circuit breaker, G, normally short-circuited by the key H, is placed in the primary of each induction coil. When the key is depressed a large number of impulses are produced in the primary, and by means of the secondary corresponding impulses are produced at the elevated condensing surface. These electrostatic impulses are transmitted inductively to surface C, and are made audible the current generated in the electromotograph connected in the ground circuit with the distant condenser plate. The intervening body of air forms the dielectric of the condenser, so that we again have the case of a circuit containing resistance, self-induction and capacity in series in which an alternating current is generated by a series of impulses of low frequency. It may be well to remark that Edison was one of the first to note the advantage of elevation for the condenser plate, as is shown by his statement in the patent; "that it is necessary on land to increase the elevation in order to reduce to a minimum the induction absorbing effect of houses, trees and elevations in the land itself."

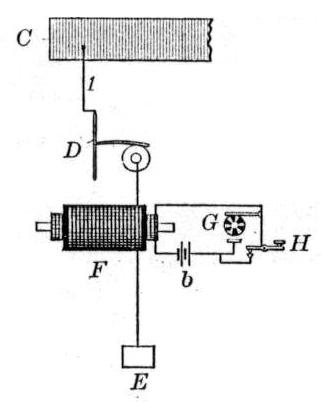

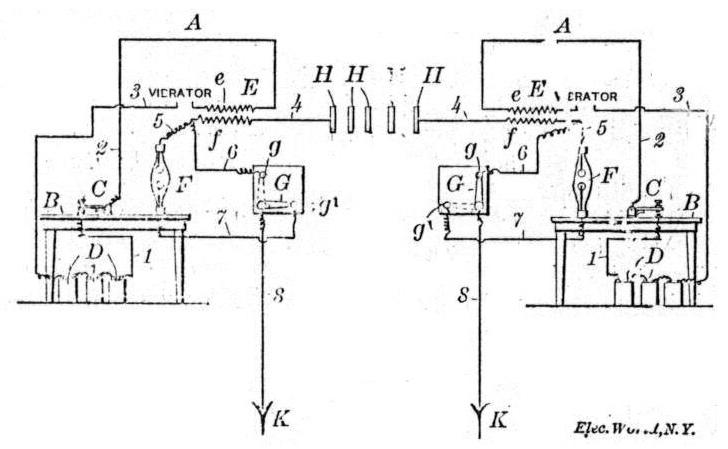

The patent to Kitsee, which forms the last one of the electrostatic induction series, resembles the Edison patent in many respects, but uses a Geissler or vacuum tube for a receiving instrument. The closing of the key, in sending a current through the wire in which the Geissler tube is intercalated, causes a discharge in the tube which produces a continuous glow as long as the key is depressed. This permits the use of a dot and dash system of telegraphy. Referring to Fig. 8, a wire leads from the earth at K, through the switch G, and then either through the secondary f or through the Geissler tube F, and secondary to the line, according as the switch G is in the transmitting or receiving position. The local or signaling circuits consists of batteries D, a key C, a vibrator and primary e. With the switches in the position shown, on depressing the key C at the right-hand station, the vibrator is started, and the current induced in the secondary f, which alternately charges and discharges the plate H. These charges act inductively on the intermediate plates H, and finally induce a charge on the left-hand plate which creates a current in the secondary f which flows through the Geissler tube F, through the switch G to earth, thus causing a glow in the tube.

Wave Methods

It seems difficult at first to separate wave methods from some of the electrostatic systems used by Dolbear, Edison and Kitsee, and indeed both may be regarded as belonging to the same generic class of induction as distinguished from conduction methods. It will serve to bring out the differences that exist between them if we digress somewhat in order to consult the examples furnished by other undulatory fields.

When sound waves are sent through the air, for instance, a great difference is recognized by the ear between a noise like the report of a cannon and a musical note. The former is produced by one or more shocks or sudden impulses, the latter by a series of waves of definite frequency and amplitude.

A similar distinction may be, recognized when solid or liquid bodies are set in vibration. If a string is fastened at one end and the other held in the hand a single impulse may be sent along it by jerking the hand to one side, or a series of impulses or waves following each other in definite order, and at a uniform distance apart, may be formed by shaking the string transversely in timed sequence.

It is difficult to imagine an impulse formed by light or heat, for the period of such a wave is so short that a great number of them, are sent out before the radian source can be eclipsed. A flash of light, which corresponds in its effect on the retina to the shock produced by a sound impulse or noise upon the tympanum, is in reality made up of a great number of waves, and is not due to a single light impulse. The persistence of impressions on the retina, the duration of which is about half a second, permits 250,000,000,000,000 light waves to act upon it before the sensation due to the first wave has died out.

In all these cases an impulse may be regarded as a single wave, but differing in shape and sometimes in velocity from the wave that exists in a train or series of undulations emitted by a suitable source of energy. In the electrical induction methods which have been described a single impulse or a number of them is generated, and these impulses produce their separate effects upon the receiver. One impulse dies out and an interval of time elapses before another is created. Their effect may be cumulative, as in the case of the Kitsee apparatus, where a series of impulses produced by depressing a key causes a continuous glow in the vacuum tube owing to the persistence of the impression on the retina, but the impulses themselves are separated by a distinct interval of time. This will more fully appear from the following considerations.

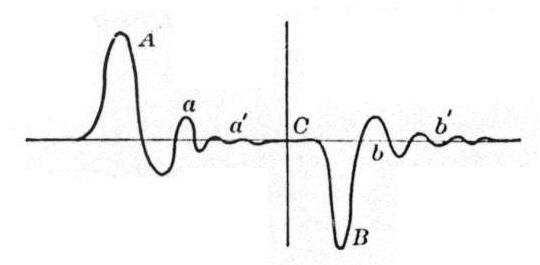

Suppose, as in the patent to Edison, 465,971, a Rhumkorff coil is used to charge the inducing plate, and assume that the current interrupter G is driven at a speed which will produce 100 breaks of the primary current per second. In each one-hundredth of a second two distinct charges of opposite sign are produced at the end of the open secondary; the one due to the make of the primary, the other to its break. In addition there are a number of oscillations of the make-induced charge as well as of the break charge. The shape of the curve which shows the charge of the ends of the secondary may be roughly indicated as in Fig. 9. This shape depends on a number of conditions, which include the resistance, self-induction and capacity of the two circuits, and is particularly affected by the presence of a condenser in the primary circuit1. For the present purpose it is sufficient to say that the curve is made up of two predominant impulses A and B, one positive and the other negative, each accompanied by a few considerable oscillations a and b, with a large number of negligible waves, a' and b', and a period of zero charge C between them. In some experiments by Bernstein2 the frequency of the oscillation was as high as 20,000 per second. If the interrupter breaks the primary 100 times a second 200 oscillations will have time to die out between two breaks. Only a few of these can be effective owing to the large dampening factor of the circuits, and in the experiments referred to perhaps thirty oscillations were measurable, of which the first two or three alone may be regarded as of the same order of intensity as that of the initially induced wave. In pure wave methods on the contrary each wave of the train exerts its influence and is as effective as any other.

Another distinction which exists between impulse and wave methods is brought out by the principle of resonance. As is well known much an oscillatory disturbance of definite period will exert a greater effect upon a system tuned to the same period than upon one differing even slightly from it. A train of waves sent out by a sounding body will set a tuning fork of the same pitch into sympathetic vibration, but will leave undisturbed a fork of slightly different pitch.

A pendulum may be made to oscillate through a large arc by a series of weak forces if we so time their application that the interval between them is equal to the period of the pendulum. This has been used in a telephone selective signal system, in which each station is provided with a single pendulum of a definite time of vibration, which is determined by the position of a weight along its length. A number of electromagnets connected in series with a battery are arranged one at each station and each in position to attract its pendulum. Each subscriber can close the magnet circuit in suitable time sequence by means of a make and break pendulum whose period can be made equal to that of the call of any of the subscribers wanted. The magnets are thus all energized at each closure of the circuit, but the pendulum at the call station is the only one that responds, since its period is equal to that of the calling pendulum.

In optics, as is well known, a ray of light of a fixed wave length emitted by the sun will be absorbed by an incandescent gas in its photo sphere, which sends out waves of the same wave length, thus produced a so-called dark line in the solar spectrum. This has enabled physicists to determine the composition of the sun and "fixed" stars.

So an electrical oscillation of a definite period will exert, other conditions being the same, a much greater inductive effect upon one of equal period than upon one differing even slightly from it. The phenomenon of resonance is absent from electrical circuits in which impulses only are produced, for in them there is either an entire absence of period or this is not fixed but variable. Or as Lodge puts it3, almost anything will respond equally well or equally ill to a dead-beat or strongly damped exciter.

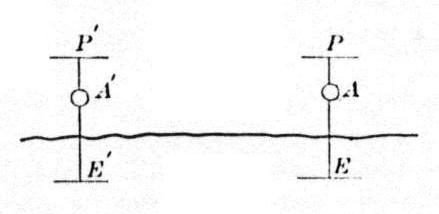

Before proceeding to the discussion of the patents that have been granted for applications of wave methods it will be desirable to consider briefly a suggestion of Tesla which relates to a method of signaling by means of high frequency currents. The scheme, which is illustrated in Fig. 10, is described in his researches edited by T. C. Martin, 1894. Assume that a source of alternating currents of high frequency A be connected with one of its terminals to earth and the other to a body of large surface P. When an electrical oscillation is set up at P this acts inductively on P', which constitutes a receiver. At any point within a certain radius of the source A a properly adjusted self-induction and capacity can be set in action by resonance. This method of signaling resembles that of the Edison patent 465,971, but an alternator is used without an induction coil, whose period, if we take for granted that a Tesla generator is referred to, may be as high as 20,000 reversals per second. No coherer is necessary, and the period of the waves emitted by the alternator, which is equal to that of the oscillations created in some of the induction methods described above, is of a much lower order than that of the Marconi and Lodge patents referred to below, in which waves are produced whose frequency may equal 10,000,000 per second. It will be seen that this device occupies an intermediate position in the development of the art.

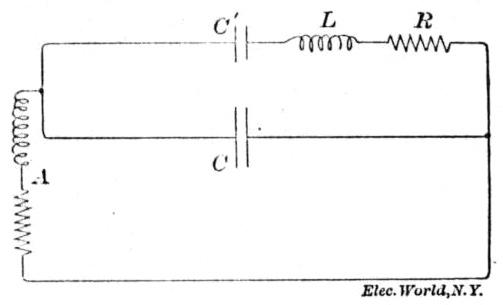

The diagram in Fig. 10a shows the arrangements of the constants of the circuit. The generator A has a given self-induction and resistance; C' denotes the condenser at the receiving station in series with a suitable relay of resistance R and self-induction L. C is the condenser formed by the sending plate with the earth. It is shown as connected across the receiving circuit.

The case may be solved by the geometrical method, if the values of the constants are known. The calculation of the latter is a matter of some difficulty, since allowance must be made for the proximity of the condensing plates to the earth. The formula for calculating the capacity of two parallel plates

$$S = \frac{A}{4\pi d}$$

assumes that the field between them is uniform, which is only true when the distance between the plates is small compared to the distance of the plates from a foreign inducing body. This condition is just the reverse of the present case in which the earth acts inductively on the plate, increasing its capacity. In the absence of any experimental data it will be misleading to calculate a theoretical effect whose value in practice may be very different. Attention is called to the fact, however, that the earth condenser C is of much larger capacity than C', so that very little current will be diverted through the receiving circuit. The capacity of the condenser C'. moreover, is very minute, so that to secure resonance the self-induction of the circuit must also be made very small according to the formula

$$T = 2\pi \sqrt{LC}$$

It is impossible to fix the value of self-induction by calculation when its value is so small; a cut-and-try method must be used until the proper length of wire is obtained which will neutralize the capacity.

The method used by Tesla, which has been described, resembles his proposed means for transmitting power at high altitudes, for which British patent 24,421 of 1897, and Swiss patent, 15,542 of 1897, have been granted to him, and is a step in the direction of his recent United States patent, 613,809, November 8, 1898, for controlling the movements and operation of a vessel or vehicle. Although both of these inventions relate to a different art, namely, that of transmitting power as distinguished from that of transmitting signals, yet by reason of their analogy to the present subject matter a brief description of them will be given. In the patent for transmitting power step-up and step-down transformers of high converting power are used, the former at the sending and the latter at the receiving station. One end of the secondary of the step-up transformer is connected to earth, the other to an insulated metallic sphere or condensing surface at a high elevation in the atmosphere. A similar arrangement is adopted at the receiving end and power is transmitted from one condenser plate to the other. The conditions which effect this method of transmission have been pointed out above.

In the patent, No. 613,809, for steering and propelling vessels a coherer circuit is used and local circuits which are energized by storage batteries for controlling the propelling and steering mechanisms. A steering motor is made to run in one direction by a local circuit thrown in by a relay and is driven in the reverse direction by another circuit and relay. The relays are energized by the coherer circuit, which includes a commutator and battery. The coherer circuit is made effective by the oscillator on shore. The boat is put into the water with the rudder to starboard, for example, the oscillator is started, the coherer is put into operation and the local circuit is thrown in which drives the rudder to port. This continues until the rudder reaches the port side. The coherer is then again operated which turns the commutator in the coherer circuit so as to throw in the local circuit which drives the rudder to starboard. The boat is thus made to steer its path in a series of zig zags. Signal lights may be flashed each time the coherer is operated to imitate the course of the vessel.

(To be continued.)

1See Colley, "Wied. Ann.," vol. 280, p. 109, and Lemstrom, "Pogg. Ann.," vol. 147, p. 354.

2"Pogg. Ann.," vol. 142, p. 54, 1871.

3See "The Work of Herz and Some of His Successes."