Nikola Tesla Articles

Telegraphing Without Line Wires - III

(Concluded from last issue.)

Two patents have been granted in this country which make use of the method of signaling by electrical waves. One is the familiar patent to Marconi, 586,193, July 13, 1897, and the other is the patent to Lodge, 609,154, August 16, 1898.

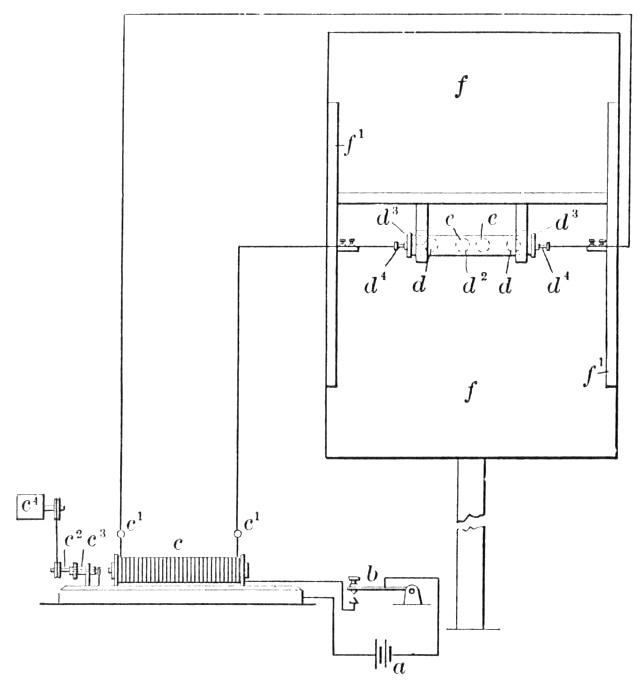

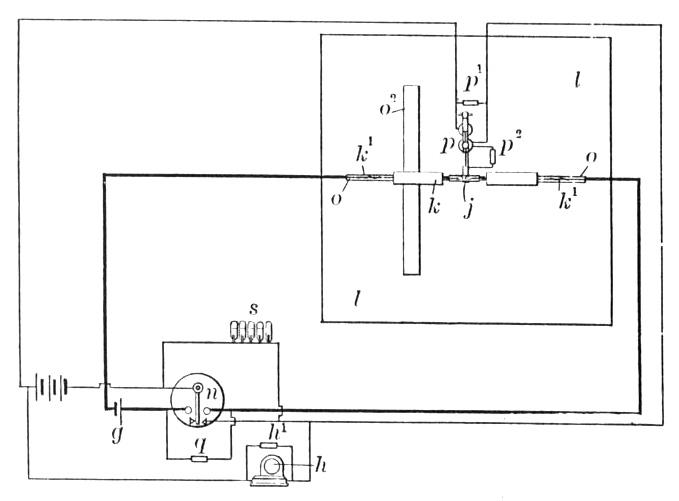

In the patent to Marconi, Figs. 11 and 12 represent the transmitter and receiving apparatus when used for short distances. In them c indicates the induction coil, whose secondary is connected to the balls d; the primary is closed through the key b. f is a reflecting mirror of metal, and the sparking apparatus is placed at its focus. The spheres e lie between the knobs d, and when the induction coil sparks across at d it also of course produces sparking at e. This spark is the result of an oscillatory charge which is induced on the sphere e, and which sends out waves through the ether to the receiver, Fig. 12. This receiver consists of the coherer j, a glass tube containing metallic powder, each end of the column of powder being connected to a metallic plate k of suitable length to cause the system to syntonize electrically with the electrical oscillation transmitted. The tube j may be replaced by other forms of imperfect electrical contacts, examples of which are given by Lodge in the monograph above cited.* See the chapter on microphonic detectors. The reflector l collects the oscillations and projects them upon the coherer. There are two circuits at the receiver; one is the circuit embracing the coherer, the plates k, the battery g, and the magnet of the relay n; the other includes the battery r, the armature of the relay n and the trembler p. These correspond respectively to the line and local circuit of the ordinary Morse telegraph.

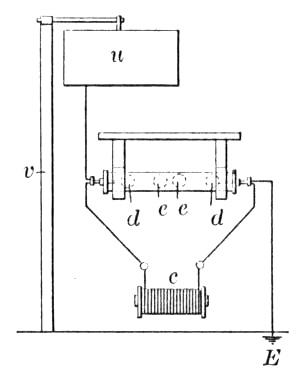

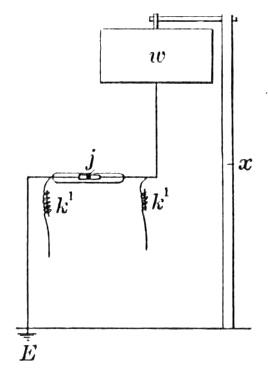

The object of the trembler or decoherer is to disturb the filings after the spark has passed, and thus once more make their resistance too high to permit the passage of the current of the battery g. This decoherer is usually an electromagnetic bell, whose hammer is arranged to strike the coherer tube. The tapping is thus done automatically by the current started by the spark in the tube. In addition to these generic features of the invention there are a number of details which are shown in the figures. A telegraphic receiver h is placed in a circuit derived from the trembler bell circuit. The other devices shown at p1 p2 h1 q and s are non-inductive resistances shunted about the electromagnets or circuit closures to counteract self-induction or prevent sparking. The arrangement usually adopted by Marconi is shown in Figs. 13 and 14, which are taken from Figs. 10 and 11 of the patent. One of the spheres d is connected to earth E and the other to a plate u suspended on a pole v and insulated from the earth. At the receiving station, Fig. 14, one terminal of the sensitive tube j is connected to the earth E and the other to an insulated plate w suspended on a pole x. The larger the plates of the receiver and transmitter and the higher the plates are suspended from the earth the greater is the distance through which it is possible to communicate. It was pointed out above that this elevation of the plates increased the proportion of the capacity of the plates with respect to each other to their capacity with respect to the earth, which augments the inductive action of one plate on the other. The theory of the coherer has been explained in several ways. The explanation given by Lodge in the monograph above referred to is that a kind of welding action between the particles takes place when the spark passes, which, of course, diminishes the resistance of the body of filings to the passage of the battery current.

Marconi describes in the specification a means of adjusting the capacity areas k so that the receiving circuit may syntonise electrically with the oscillations of the transmitter. In most of the experiments carried out by him with this apparatus, however, no tuning was attempted, and in the latest results that have been obtained by Slaby, circuits out of tune were used and a number of the minor features of the invention, such as the high shunted resistances to avoid sparking were omitted.

The patent to Lodge marks an important step in advance in this art. In the first place the waves emitted by the transmitter last longer, i. e., a greater number of waves are sent out at each discharge of the transmitter before they are damped out. Secondly, the receiver can be more effectively tuned or syntonized to respond to a definite pitch of the signaling instrument. Lodge's invention is shown in Figs. 15, 16 and 17, which are copies of Figs. 3, 4 and 13 of the patent.

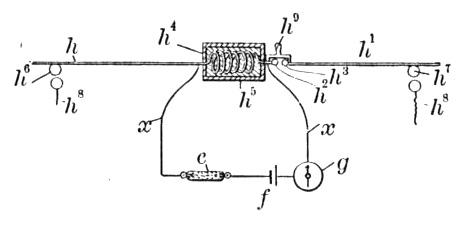

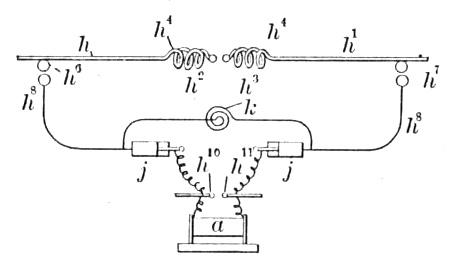

Fig. 15 shows a combined radiator and receiver. In it h8 indicates wires leading to the Ruhmkorff or high potential coil: h and h1 constitute the capacity areas, h4 is the syntonizing self-induction coil embedded in insulation h5; h9 is a sort of circuiting switch; e is the coherer, f the battery and g the receiving instrument. When in use as a radiator the gap between the discharge knobs h2 and h3 is left open; when utilized as a receiver the gap is closed by the switch and the coherer, battery and receiving instrument g are connected through a thin wire x from each end of the coil h4. The above arrangement permits one instrument to be used as a transmitter or receiver by simply throwing a switch. In Fig. 16 a Leyden jar or other suitable condenser j, able to stand a high potential, is interposed in the wires h8, leading from the Ruhmkorff coil, so that the knobs are supplied from the outer, that is, the uninsulated coat of each jar, while between the inner coats a third spark gap is arranged, called the starting gap, which consists of suitable knobs, h10 h11. The outer coats of the jars are joined by an induction coil of thin wire, k, so as to permit thorough charging. When the discharge occurs, this wire acts as an alternative path or bypass, but does not prevent the sparks at the supply gap.

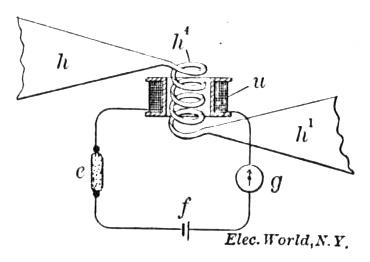

In Fig. 17 the syntonizing coil of the resonator is surrounded with another or secondary coil u, constituting a species of transformer. This latter coil is made a part of the coherer circuit, so that it is secondarily affected by the alternating currents excited in the conductor of the resonator. The coherer is thus stimulated by the current in this secondary coil rather than primarily by the currents in the syntonising coil itself, the idea being to thus leave the resonator freer to vibrate electrically without disturbance from attached wires.

The persistance of vibration of the waves of the transmitter is due to the self-induction coil which is inserted between the capacity areas of the radiator. This effect is analogous to that due to increasing the weight, and therefore the moment of inertia of a flywheel which prolongs the number of revolutions the wheel makes, beginning with a given angular velocity, before it comes to rest. The following extract from Helmholtz's "Sensations of Tone," page 62, may make the action of the induction coil clearer by setting forth the parallel case for sounding bodies:

"Bodies of small mass which readily communicate their motion to the air and quickly cease to sound, as for example stretched membranes or violin strings, are readily set in sympathetic vibration. The limits of pitch capable of exciting sympathetic vibration in such bodies are somewhat broad. Massive elastic bodies, on the other hand, such as bells and plates, are not so easily excited. It is necessary to hit the pitch of their tone with much greater nicety in order to make them vibrate sympathetically. They will, of course, continue to vibrate for a longer period than the others."

Attention is called to the persistency of the sounds of heavy elastic bodies and nicety of regulation, which is required to set them in sympathetic vibration, just as in an electric circuit containing an induction coil, as used by Lodge, the oscillations last longer and the syntony is more accurate than when the coil is omitted.

With the patent to Lodge it will be necessary to bring this article to an end. It will be readily granted that there are still numerous problems to be solved in the art of wireless telegraphy. It will be necessary to increase the distance over which transmission may be effected, to add to the certainty and secrecy of the message, to prevent the disturbing and absorptive effects of the intervening media, to increase the sensitiveness without impairing the efficiency of the receiving instrument, before we can hope to replace the Atlantic cable and its costly appurtenances with a pair of syntonized radiators and receivers.

October, 1898.

* See "The Work of Hertz and Some of His Successes."