Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla, at 76, Calls Radio His Despised 'Child'

It Is a Nuisance and Distraction, Says Inventor of Electrical Devices

Seeks New Power Source

Secret Experiments Aiding in 'Greatest Discovery'

Nikola Tesla, pioneer of radio. thinks it is a nuisance.

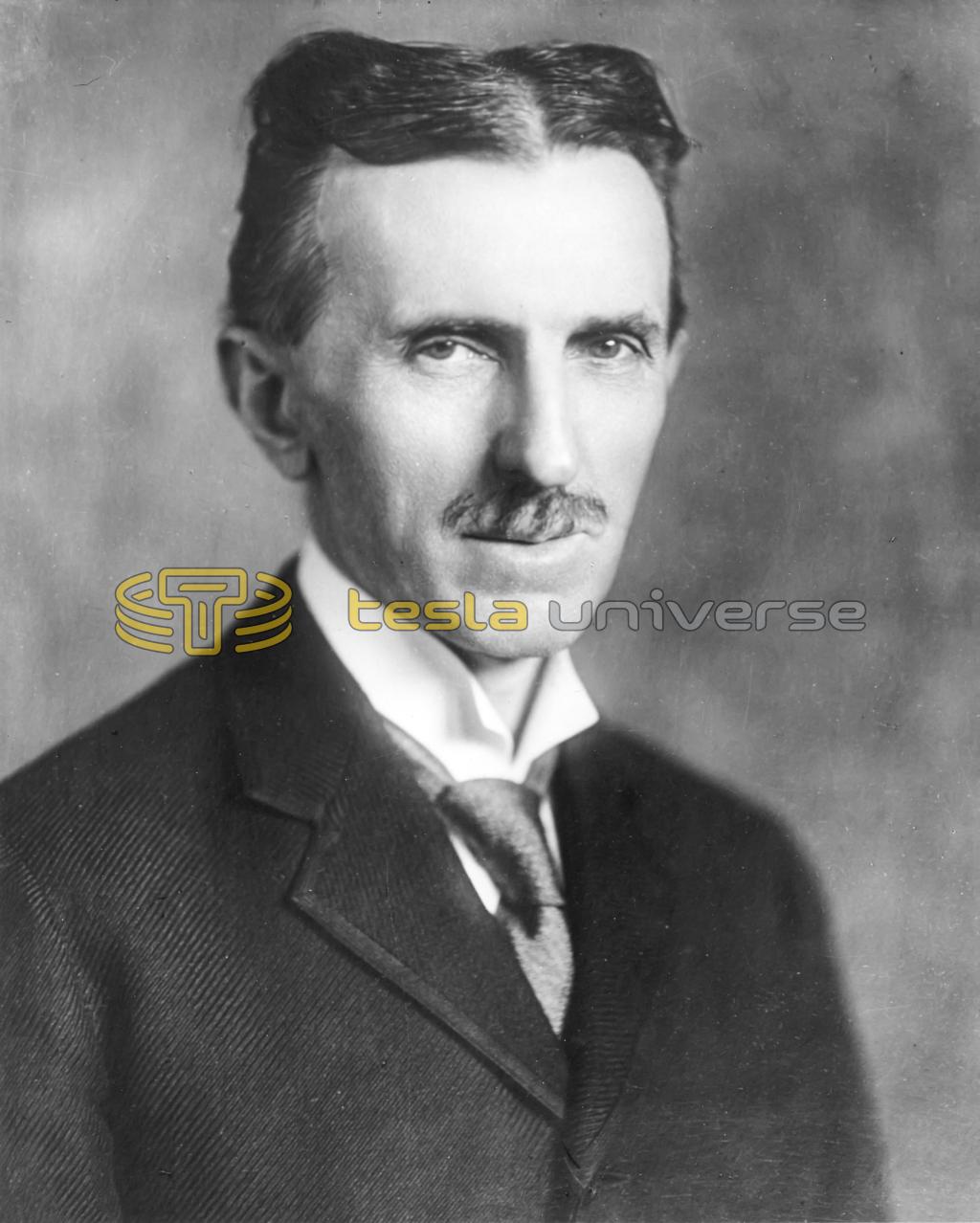

The world famous electrical inventor expressed this opinion with some warmth last evening as he looked back contemplatively over the career which has brought him today to his seventy-sixth birthday. He was interviewed in the Governor Clinton Hotel, where he makes his bachelor home.

This hotel has a radio in every room. But Mr. Tesla's complaint was not so much a matter of his neighbor's music as it was a matter of personal taste.

"The radio, I know I'm its father. but I don't like it," he said. "I just don't like it. It's a nuisance. I never listen to it. The radio is a distraction and keeps you from concentrating. There are too many distractions in this life for quality of thought; and it's quality of thought, not quantity, that counts."

Mr. Tesla. who sent a radio impulse around the world thirty-five years ago, who discovered the rotating field principle for alternating currents, and whose name is the identifying tag on more than 100 devices and improvements in electrical technology. enters his seventy-seventh year in full confidence that he will yet give to the world his greatest discovery.

This, as he announced on his birthday last year, is a new and hitherto unknown source of power. the nature of which he has refused to give any hint. Asked about it yesterday, he said:

"I am gratified to say that during the year I have made very satisfactory progress in theoretical as well as experimental respects. I have found explanations for results which puzzled me last year, and I have advanced considerably toward the realization of a workable machine. The theoretical design of apparatus for practical use has been so much simplified that the results can be depended upon within a small margin of error. I realize, though, that my difficulty will be in the necessity of making an installation on a very large scale, implying considerable first outlay. But I have had a happy idea lately, and it may lead to a great reduction in the size and cost of the plant.

"You understand that this new source of power has nothing to do with those hitherto known. as for instance, heat and light rays, ebb of tides, or the heat of the oceans and continents. It also has nothing to do with my plans for wireless transmission of power, or with my studies of the cosmic rays. If I succeed practically, we will be enabled to derive power in large amounts, absolutely without regard to location, and the power will be almost constant."

Tall. spare, erect, wearing a cutaway coat and carry stick and gloves, Mr. Tesla receives his visitors on the mezzanine of his hotel, looking twenty years younger than his three score and sixteen. Since he met financial reverses fifteen years ago, and during the last decade of monumental developments in the science he so influenced, he has lived a secluded life in the midst of the city. His greatest pleasure has been the feeding of pigeons before the Public Library, and the care of injured birds.

His latest work, he says, has been carried on in a small laboratory of secret location in this city: and two or three other men have helped him in laboratories elsewhere, where he has use of the facilities. He passed yesterday working and expects to do the same today, if indeed it can be called work.

"With me it's just a choice between pleasures," he said. "I have no plan or schedule, and never have had. When I start the day, it's just a choice among pleasures, as to which problem I shall work on."

As Mr. Tesla's life goes on, he becomes more and more convinced that there is no future existence and that this life is entirely a matter of materialistic phenomena.

"We are all automata, nothing else." he said. "And yet I have a certain idealism. There is an ideal striving which is the effort of the human mind to free itself from materialistic fetters. But there is no individuality. You wouldn't say a wave on the ocean had individuality. It is a succession of waves. You are not the same person today that you were yesterday. I am just a concatenation of existences which are nearly, but not exactly, alike. It is this concatenation which produces the effect of continuance, like a motion picture. What Tesla gives to posterity is not the product or Tesla, but of a succession of existences."