Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla Effects with Simple Apparatus

BY H. M. MARTIN AND W. H. PALMER, JR.

All who visited the room in the Electricity Building at the World's Fair in which Mr. Tesla's high frequency apparatus was exhibited must have brought away with them a lively desire to repeat at their leisure the beautiful and interesting experiments there shown; but a recollection of the many expensive appliances used in obtaining the effects has doubtless deterred many from entering upon what must prove a valuable and absorbing line of study. It is the object of this paper to show that no one need fear failure in this field who has at his command the simple apparatus to be found in the most unpretentious laboratory; nor should it be thought that results are less instructive or of smaller scientific value when obtained in this way than when obtained by the use of more powerful apparatus.

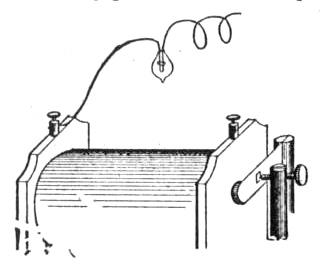

Some years ago the writers, while testing a small Ruhmkorff coil, connected up a burnt-out miniature incandescent lamp between the secondary terminals. On closing the primary circuit the usual violent discharge was set up between the broken ends of the carbon. While the current was on one of the connections became unfastened, leaving the lamp joined to only one of the coil terminals, as in Fig. 1; and the discharge instead of being extinguished, changed to a soft glow that filled the whole interior of the lamp. This was, on a small scale, identical with the experiment performed so brilliantly by Mr. Tesla during his London lecture, when he lighted an exhausted bulb, having a sealed-in electrode, through a single lead from a source of high potential and frequency.

Although this experiment was often repeated, its significance was not realized until Mr. Tesla made known the results of the researches which have entitled him to rank among the foremost investigators of our times. But the published report of the lecture placed the previous experiment in its true light, and inspired a hope that other effects might be duplicated with the feeble apparatus at hand. The results have more than fulfilled our expectations. The necessary potential and frequency were obtained from a small Ruhmkorff coil capable of giving a quarter-inch spark when operated by three Bunsen cells.

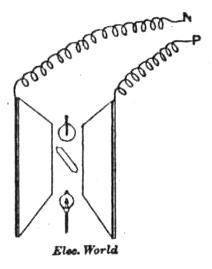

Two insulated metallic plates 12"x12" in size were placed about three inches apart and connected with the terminals N and P (see Fig. 2). Exhausted bulbs, miniature incandescent lamps, Geissler tubes, etc., were then introduced between the plates, and glowed brightly without any direct connection with the plates or coil. Actual photometric measurements of the maximum light emitted by this arrangement show it to be greater than that obtainable by using the current directly in an incandescent lamp. This is significant as showing the poor economy of the present methods of electric lighting, and leads us to believe that molecular bombardment electrostatically sustained contains great possibilities in this connection.

A slight modification of this arrangement makes it possible to dispense with one of the two plates. In all these experiments the battery cells act as a species of reservoir or condenser, so that tubes and bulbs lying in their vicinity are often seen to glow brightly and fade, in proportion as the capacity of the apparatus is changed.

Incandescent lamps may be lighted through a single lead from one of the secondary terminals; this effect is greatly heightened if. the hand or some other object of capacity is placed near the lamp bulb. The small 6 c. p. lamps are peculiarly adapted for use in these experiments, their shape seeming to concentrate the molecular bombardment upon the carbon filament.

If a good mercurial air-pump is not accessible, vacuum tubes that will serve for want of better may be obtained by heating mercury in a piece of tubing, and sealing the end after the mercury has reached the boiling point. A pretty experiment may be performed by holding the exhausted tube in one hand, with one end near the coil terminal, and then passing the other hand down the length of the tube, extinguishing the glow and giving the effect, as a friend expressed it, of "wiping the moonshine off."

Many other combinations will suggest themselves to the investigator, but there is one experiment which, since it depends upon a principle that has not, to the writer's knowledge, received as yet any published explanation, should be of special interest. This phenomenon, a description of which has already appeared in blad be these columns,* may be satisfactorily observed with the small induction coil by proceeding as follows:

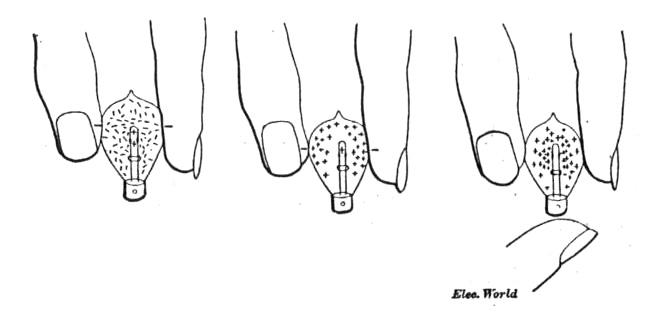

Holding the bulb of a miniature incandescent lamp in the hand, bring the leading-in wire into contact with the coil terminal; the bulb will be filled with the usual phosphorescent glow. If, now, the lamp is slowly withdrawn from contact with the terminal, this light will gradually fade, as the confines of the field are approached, and concentrate itself around the interior carbon. Soon a point will be reached beyond which the glow does not diminish through further removal from the coil. It is now quite self-sustained, and cutting the current off from the coil will not effect it in any perceptible way. This phenomenon we have called the "afterglow."

When obtained in this way, the afterglow will continue for from one to two minutes after the coil is shut off. The lamp may be carried glowing from room to room; if put down out of the hand the light becomes fainter, but is not extinguished. After some minutes, when the glow has faded quite away, a sudden flash may be observed if the leading-in wire is touched with the finger. Several of these flashes may sometimes be obtained before the bulb is entirely discharged.

It must not be supposed that this glow is due to heat remaining in the lamp carbon, the heating effect of so weak a coil being quite insignificant. A consideration of the accompanying figures will show the purely electrostatic nature of this phenomenon.

When the lamp is withdrawn from the alternating field, the interior electrode retains a charge differing in sign or intensity from that of the rarefied gas in the bulb and that induced in the fingers of the experimenter, Fig. 3. The natural consequences of this state of unequal charge are molecular bombardments and collisions more violent in the immediate neighborhood of the electrode, because of the small surface over which its charge is distributed. When electrical equilibrium has been established between the gas molecules and the electrode, this interchange of charge ceases, and the glow dies away. The condition of affairs at this moment is shown in Fig. 4.

Discharging the electrode will now cause a sudden rush of molecules toward it to re-establish equilibrium (see Fig. 5), giving rise to the momentary flash observed, and this may be repeated until no charge remains in the lamp.

This is, perhaps, the simplest arrangement ever devised for obtaining light from electricity, and it may not be extravagant to say that it embodies the fundamental principles of an economical system of artificial illumination.

* "The Afterglow in Exhausted Bulbs," The Electrical World, Jan. 20, 1894.