Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla on the Electrical Transmission of Energy

The following extract from the long lecture delivered recently by Mr. Nikola Tesla will be found of especial interest from several points of view: — Some enthusiasts have expressed their belief that telephony to any distance by induction through the air is possible. I cannot stretch my imagination so far but I do firmly believe that it is practicable to disturb, by means of powerful machines, the electrostatic condition of the earth, and thus transmit intelligible signals and perhaps power. In fact, what is there against the carrying out of such a scheme? We now know that electric vibration. may be transmitted through a single conductor. Why, then, not try to avail ourselves of the earth for this purpose? We need not be frightened by the idea of distance. To the weary wanderer counting the mile-posts the earth may appear very large; but to that happiest of all men, the astronomer, who gazes at the heavens and by their standard judges the magnitude of our globe, it appears very small. And so I think it must seem to the electrician, for when he considers the speed with which an electric disturbance is propagated through the earth, all his ideas of distance must completely vanish.

A point of great importance would be, first, to know what is the capacity of the earth and what charge does it contain if electrified? Though we have no positive evidence of a charged body existing in space without other oppositely electrified bodies being near, there is a fair probability that the earth is such a body, for by whatever process it was separated from other bodies — and this is the accepted view of its origin — it must have retained a charge, as occurs in all processes of mechanical separation. If it be a charged body insulated in space, its capacity should be extremely small, less than one-thousandth of a farad. But the upper strata of the air are conducting, and so, perhaps, is the medium in free space beyond the atmosphere, and these may contain an opposite charge. Then the capacity might be incomparably greater. In any case, it is of the greatest importance to get an idea of what quantity of electricity the earth contains. It is difficult to say whether we shall ever ac- quire this necessary knowledge, but there is hope that we may, and that is by means of electrical resonance. If ever we can ascertain at what period the earth's charge, when disturbed, oscillates with respect to an oppositely electrified system or known circuit, we shall know a fact possibly of the greatest importance to the welfare of the human race. I pro- pose to seek for the period by means of an electrical Oscillator, or a source of alternating electric currents. One of the terminals of the source would be connected to earth, as, for instance, to the city water mains, the other to an insulated body of large surface. It is possible that the outer conducting air strata or free space contains an opposite charge, and that, together with the earth, they form a condenser of very large capacity. In such case the period of vibration may be very low, and an alternating dynamo machine might serve for the purpose of the experiment. I would then transform the current to a potential as high as it would be found possible, and connect the ends of, the high tension secondary to the ground and to the insulated body. By varying the frequency of the currents and carefully observing the potential of the insulated body, and watching for the disturbance at various neighboring points of the earth's surface, resonance might be detected. Should, as the majority of scientific men in all probability believe, the period be extremely small, then a dynamo machine would not do, and a proper electrical oscillator would have to be produced, and perhaps it might not be possible to obtain such rapid vibrations. But whether this be possible or not, and whether the earth contains a charge or not, and whatever may be its period of vibration, it certainly is possible — for of this we have daily evidence — to produce some electrical disturbance sufficiently powerful to be perceptible by suitable instruments at any point of the earth's surface.

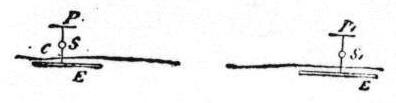

Assume that a source of alternating currents S be connected, as in the figure, with one of its terminals to earth (conveniently to the water mains) and with the other to a body of large surface P. When the electric oscillation is set up, there will be a movement of electricity in and out of P, and alternating currents will pass through the earth, converging to or diverging from the point C where the ground connection is made. In this manner neighbouring points on the earth's surface within a certain radius will be disturbed. But the disturbance will diminish with the distance, and the distance at which the effect will still be perceptible will depend on the quantity of electricity set in motion. Since the body P is insulated, in order to displace a considerable quantity the potential of the source must be excessive, since there would be limitations as to the surface of P. The conditions might be adjusted so that the generator or source S will set up the same electrical movement as though its circuit were closed. Thus it is certainly practicable to impress an electric vibration at least of a certain low period upon the earth by means of proper machinery. At what distance such a vibration might be made perceptible can only be conjectured. I have on another occasion considered the question how the earth might behave to electric disturbances. There is no doubt that, since in such an experiment the electrical density at the surface could be but extremely small considering the size of the earth, the air would not act as a very disturbing factor, and there would be not much energy lost through the action of the air, which would be the case if the density were great. Theoretically, then, it could not require a great amount of energy to produce a disturbance perceptible at great distance or even all over the surface of the globe. Now, it is quite certain that at any point within a certain radius of the source S a properly adjusted self-induction and capacity device can be set in action by resonance. But not only can this be done, but another source S₁, similar to S, or any number of such sources can be set to work in synchronism with the latter and the vibration thus intensified and spread over a large area, or a flow of electricity produced to or from the source S, if the same be of opposite phase to the source S. I think that, beyond doubt, it is possible to operate electrical devices in a city through the ground or pipe system by resonance from an electrical oscillator located at a central point. But the practical solution of this problem would be of incomparably smaller benefit to man than the realisation of the scheme of transmitting intelligence or perhaps power to any distance through the earth or environing medium. If this is at all possible distance does not mean anything. Proper apparatus must first be produced by means of which the problem can be attacked, and I have devoted much thought to this subject. I am firmly convinced that it can be done, and hope that we shall live to see it done.