Nikola Tesla Articles

The Tesla Motor - An Entirely New Principle

To the Editor of Electrical Review:

The Tesla alternating current motor is entirely different from the very old class of devices, to one of which Mr. Kintner refers on page 1 of your issue of June 30, and in all of which devices motion is transmitted by impulses of currents moving in opposite directions in comparatively slow succession. In fact the first telegraph of Gaus and Weber in 1835 was operated by alternate currents acting upon a galvanometer needle, deviating it to the right and left; while Steinheil, in order to make the signals audible, added to this, in 1838, two bells of different pitch which were alternately struck when the needle was deflected right or left, and also in order to make a permanent record, he moved strips of paper by machinery and made dots on it by furnishing the needle with a tube containing ink.1

Most of the submarine cables are now worked by means of alternate currents and this for an important additional reason, namely, a long insulated conductor acts like a very elongated Leyden jar and becomes charged at the transmission of every signal, while the following reverse current neutralizes this charge, reducing the time required between the signals, and thus increasing the capacity of the cable. In this case the signs are made visible by attaching to the needle a small mirror which reflects the light of a lamp as a white spot on a scale, and is moving right or left with the alternate movements of the needle impelled by alternate currents. Again, the rapid telegraph system operated by strips of perforated paper, is worked by alternating currents.

The London standard clock, referred to by your correspondent, is only another application of this very same device, being also actuated by currents generated by the action of permanent magnets upon bobbins or coils, as was the case with the telegraph signals of Gaus and Weber in 1835; the only difference being that in the clock the currents alternate continually at equal periods of time.

It is thus seen that the principle upon which Varley's electric clock operates is anticipated by Gaus and Weber's device of 1835, but none of those devices have the least relation to the motor of Mr. Tesla, which is based on the practical application for motive power of the torrent of electric currents produced by an alternating dynamo, which currents succeed one another with the astounding rapidity of some twenty thousand alternations per minute.2

It is self-evident that such a current can not act upon a galvanometer, nor charge electro-magnets, for reason that the opposite currents continually neutralize one another, wherefore they cannot be measured by the ordinary appliances used for continuous currents, nor can such a current give the least movement to any electric motor based upon attraction and repulsion of electro magnets, whatever be its type.

Mr. Tesla's alternating current motor is based on an entirely new principle which must be carefully studied to be understood, and it is only the want of the latter which may cause it to be confounded with the various other devices referred to above, of which the alternations amount to 4 per second at the most, while the Tesla motor work with some 400 alternations per second.

It is evident that the ordinary type of electro-motors is here out of the question, and Mr. Tesla's merit consists in the application of a very different principle discovered by him and the construction of a very peculiarly arranged motor invented by him.

While congratulating Mr. Tesla with his success in this new path of pursuit, I cannot leave him without bringing to his notice an oversight he makes in his address on May 16th to the American Society of Electrical Engineers, as published in the Electrical Review of May 20th. He says: "In reality * * * all machines are alternate current machines, the currents appearing as continuous only in the external circuit, during their transit from generator to motor. In view simply of this fact, alternate currents would commend themselves as a more direct application of electric energy, and the employment of continuous currents would only be justified if we had dynamos which would primarily generate, and motors which would be directly actuated by such currents."

The oversight I refer to is that Mr. Tesla only has in view the first machines of Siemens, Halske, Wilde, Ladd, Weston's first electro-plating machine, Moehring, Baur, Brush, and a few others of the same type, in all of which alternate currents are produced, which by the commutator are brought in the same direction. If we had no other machines as such, Mr. Tesla's remark would be correct, but the fact is that we have dynamos which will primarily generate, and motors which will be directly actuated by such currents.

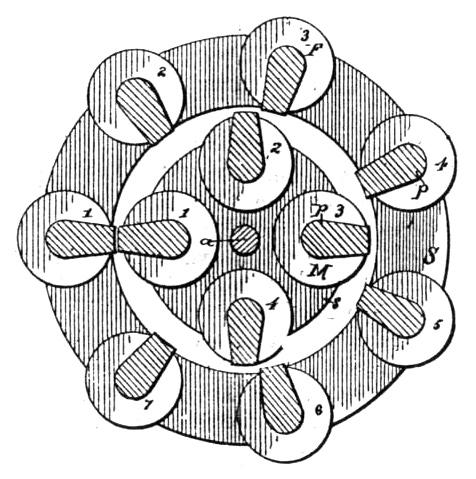

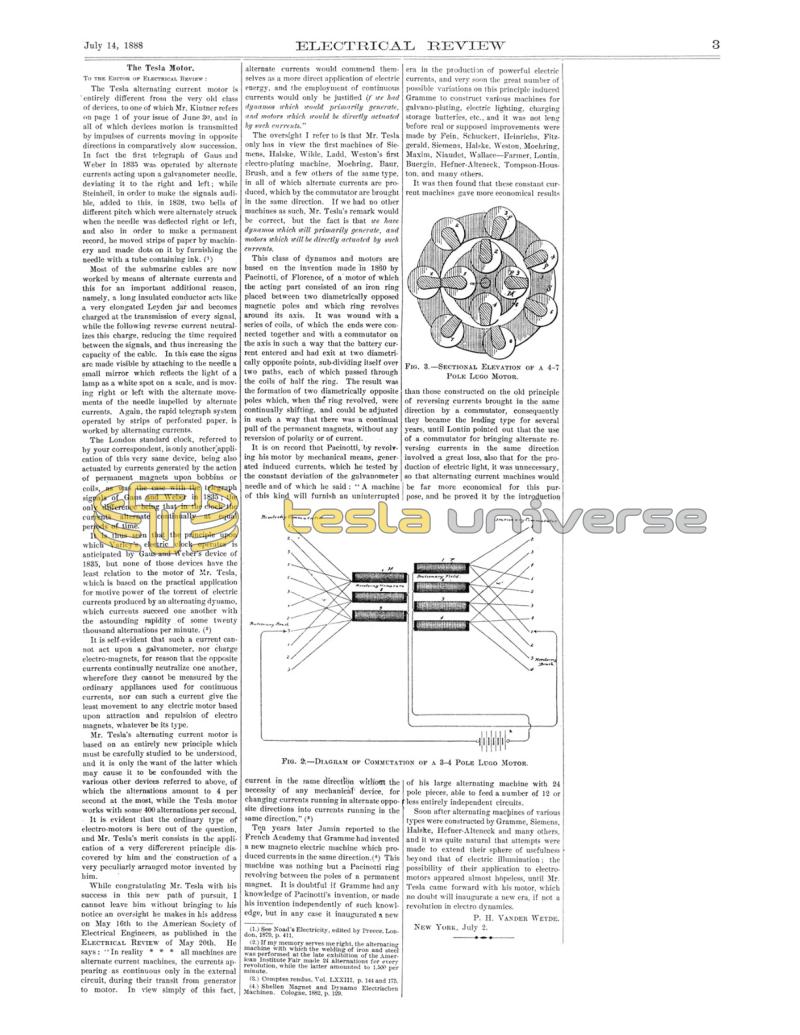

This class of dynamos and motors are based on the invention made in 1860 by Pacinotti, of Florence, of a motor of which the acting part consisted of an iron ring placed between two diametrically opposed magnetic poles and which ring revolves around its axis. It was wound with a series of coils, of which the ends were connected together and with a commutator on the axis in such a way that the battery current entered and had exit at two diametrically opposite points, sub-dividing itself over two paths, each of which passed through the coils of half the ring. The result was the formation of two diametrically opposite poles which, when the ring revolved, were continually shifting, and could be adjusted in such a way that there was a continual pull of the permanent magnets, without any reversion of polarity or of current.

It is on record that Pacinotti, by revolving his motor by mechanical means, generated induced currents, which he tested by the constant deviation of the galvanometer needle and of which he said: "A machine of this kind will furnish an uninterrupted current in the same direction without the necessity of any mechanical device, for changing currents running in alternate opposite directions into currents running in the same direction."3

Ten years later Jamin reported to the French Academy that Gramme had invented a new magneto electric machine which produced currents in the same direction.4This machine was nothing but a Pacinotti ring revolving between the poles of a permanent magnet. It is doubtful if Gramme had any knowledge of Pacinotti's invention, or made his invention independently of such knowledge, but in any case it inaugurated a new era in the production of powerful electric currents, and very soon the great number of possible variations on this principle induced Gramme to construct various machines for galvano-plating, electric lighting, charging storage batteries, etc., and it was not long before real or supposed improvements were made by Fein, Schuckert, Heinrichs, Fitzgerald, Siemens, Halske, Weston, Moehring, Maxim, Niaudet, Wallace - Farmer, Lontin, Buergin, Hefner-Alteneck, Tompson-Houston, and many others.

It was then found that these constant current machines gave more economical results than those constructed on the old principle of reversing currents brought in the same direction by a commutator, consequently they became the leading type for several years, until Lontin pointed out that the use of a commutator for bringing alternate reversing currents in the same direction involved a great loss, also that for the production of electric light, it was unnecessary, so that alternating current machines would be far more economical for this purpose, and he proved it by the introduction of his large alternating machine with 24 pole pieces, able to feed a number of 12 or less entirely independent circuits.

Soon after alternating machines of various types were constructed by Gramme, Siemens, Halske, Hefner-Alteneck and many others, and it was quite natural that attempts were made to extend their sphere of usefulness beyond that of electric illumination; the possibility of their application to electromotors appeared almost hopeless, until Mr. Tesla came forward with his motor, which no doubt will inaugurate a new era, if not a revolution in electro dynamics.

- See Noad's Electricity, edited by Preece, London, 1879, p. 411.

- If my memory serves me right, the alternating machine with which the welding of iron and steel was performed at the late exhibition of the American Institute Fair made 24 alternations for every revolution, while the latter amounted to 1.500 per minute.

- Comptes rendus, Vol. LXXIII, p. 144 and 175.

- Shellen Magnet and Dynamo Electrischen Machinen. Cologne, 1882, p. 129.