Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla & Radio

This year, 1996, is the Centennial of Radio, if it is accepted that Guglielmo Marconi is its inventor and that 1896, the date of his British patent, is the beginning of a hundred years of radio. There likely will be numerous articles, programs, and books forthcoming to celebrate the anniversary.

Some of these have already begun to appear, and, almost without exception, they attribute the invention of radio to Guglielmo Marconi, just as encyclopedias, general history books, and general science schoolbooks have continued to do, despite the fact that many scientists - electronic and electrical engineers, physicists, and radio experts - disagree.

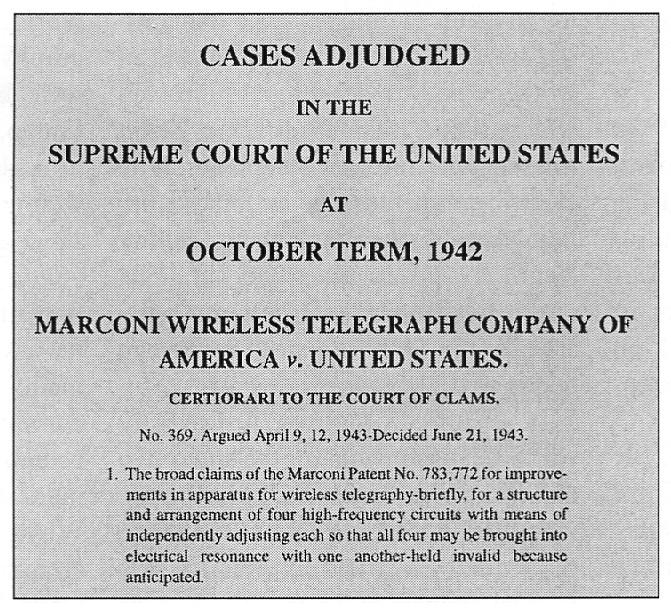

For many years, the experts have argued scientifically that Nikola Tesla, who was born in Smiljan, Lika, and was the son of a Serbian Orthodox priest, was the inventor of most of the fundamental radio devices. The 1943 US Supreme Court decision actually ruled that Tesla especially, and a few others as well, had anticipated all the features of the American Marconi radio patent of 1904 and, by implication, the preceding British patent of 1896.

Nikola Tesla, who had lived in America for the better part of his long life and was a naturalized American citizen, died in New York on Serbian Christmas, January 7, 1943. He did not live to see his priority in radio established by the Supreme Court decision of June 21, 1943.

This was a fairly old case initiated by the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America against the United States Government for infringements of Marconi's patents during World War I (1914-1918). That the Marconi Company lawsuit against the US took nearly thirty years to settle is probably due to the complexity of the history of science and technology at the turn of the century as well as the legal obfuscations of such an important case with so much at stake.

In the early 1890's, in both public lectures and publications, Tesla had freely given some of his radio related inventions and ideas to the world before he even thought about patenting them. His initial thoughts about wireless communication were noncommercial - envisioning the transmission of knowledge around the globe. This was his creative peak, and he was financially secure at this time. His major value for money was to fund his researches, which were often extremely expensive.

Later, in 1915, after he had patented several radio devices and became nearly bankrupt while attempting to develop a worldwide broadcasting system, he did attempt to sue Marconi and company, but he was then financially unable to pursue the case. Fortunately, the government did it for him, but it took almost thirty years. Some history of radio science is definitely required in order to understand what transpired both in terms of scientific discovery and practical applications.

Tesla did not discover radio waves. Nor did Marconi. Tesla was seventeen years old, and Marconi was not yet born in 1873 when the great Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell published his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism and postulated the existence of electromagnetic radiations beyond light and heat in the region of the spectrum that is now called radio waves. Maxwell mathematically developed and extended the theories of the Englishman Michael Faraday; related electricity, magnetism and light; and predicted the existence of other invisible radiations in addition to heat, all traveling at the speed of light, 186,282.396 mi/sec. Heat and light were detectable, but how could the other invisible rays be produced and detected?

Heinrich Hertz, a German physicist, first produced, detected and described radio waves between 1878 and 1888, and, of course, the devices he used were something like a primitive radio system. He demonstrated that radio waves travel at the speed of light and were reflectable and bendable like light waves. Hertz's discoveries confirmed Maxwell's electromagnetic theory, and the unit of frequency, the hertz, was later named in his honor. For a time radio waves were known as "Hertzian waves."

Hertz's apparatus was fundamentally important to all radio pioneers. The Hertzian radio wave experiment made use of an electrical, spark gap oscillator which functioned as a transmitter. The spark gap oscillator had been devised by the American Joseph Henry in 1842, and the periodicity of its spark discharge had been described mathematically by the Scotsman William Thomson in 1853.

Two metal spheres, upon which the charge accumulates through the action of an electric generator, are connected to two copper rods separated by an air gap, across which an air popping spark or arc periodically jumps, closing that open circuit and shutting down the electric charging machine temporarily. With the charge discharged and the air gap restored, the electric generator starts up again until the discharge occurs again. It had already been noted that the apparatus oscillated or changed the flow of electricity from a maximum to a minimum, just as the gap sparked and popped at regular intervals.

What Hertz did that others had not done was to detect radio waves emanating from the oscillator (functioning as a transmitter) by means of a similar spark gap resonator (functioning as a receiver) on the other side of the room. Hertz's receiver consisted of a rectangle of wire connected to the knobs of a spark gap which only sparked when the wire and the gap were of such a length as to make the receiver circuit resonant to the wave lengths from the transmitter. Hertz used large area metal plates in the open circuit and variable length vertical wires to vary the capacity and wave length to which the receiver was responsive.

By adjusting the capacity of both the transmitting and receiving circuits to the same frequency he obtained maximal periodic responses. He was able to calculate the frequencies and wave lengths of radio waves, and he determined the velocity of their spread by dividing the wave lengths by the period of oscillation. In this way Hertz found that the velocity of radio waves was approximately the speed of light; he further found that the invisible waves could be reflected and bent like visible light waves.

Hertz recognized the principle of electrical resonance or tuning, and the Hertzian oscillator resonator was the forerunner of the radio. The Hertzian oscillator transmitter had a closed circuit with a circuit breaker coupled inductively with an open circuit which included the spark gap. The transmission was weak because the oscillations were damped and the voltages which built up were low, because the generator was shut off with the discharge. The Hertzian apparatus was ungrounded, and grounding is required for true radio. It was Tesla who first described grounding in this context.

In his continuing researches with generators in the late 1880's and early 1890's, Tesla developed high frequency alternators or generators and the Tesla coil, a step up transformer which converts low voltage high amperage current with low frequencies into high voltage low amperage current with high frequencies which are desirable for radio transmission. The electrical oscillator he designed and shared with the world in the early 1890's was a powerful transmitter, and he noted that in his public lectures. The Tesla oscillator was used by Marconi in the late 1890's in making his longer range transmissions, but Marconi said that he got his inspiration to develop wireless telegraphy or "radio" after reading an article on the Hertzian experiment in an electrical journal while vacationing in the Swiss Alps.

Radio or electronic engineers and physicists define a radio communication system as one having two tuned circuits each at the transmitter and at the receiver with all four tuned to the same frequency. Tesla was the first to demonstrate the four tuned circuits. Neither the Hertzian oscillator resonator nor the first Marconi wireless set had them.

Hertz's work was described in a series of articles by G.W. de Tunzelmann in the London Electrician in 1888, and presumably Tesla learned of them from this source and others at the time when he was still working for George Westinghouse on alternating current production. Tesla left the employ of Westinghouse in the fall of 1889, and over the next four years, he worked intensively on high frequency and high potential current production and properties, electrical and mechanical oscillators, and ideas related to the wireless transmission of power and signals.

Tesla made his first public demonstration of a radio system at St. Louis to the National Electric Light Association in the spring of 1893. H.P. Broughton was the young man who assisted Tesla there. In 1976 his son, William Broughton, described his father's recollection of the event in a dedication speech for Schenectady Museum's Memorial Amateur Radio Station W21R:

"... On the auditorium stage a demonstration was set up by using two groups of equipment.

"In the transmitter group on one side of the stage was a 5-kwa high voltage pole type oil filled distribution transformer connected to a condenser bank of Leyden jars, a spark gap, a coil and a wire running up to the ceiling.

"In the receiver group at the other side of the stage was an identical wire hanging from the ceiling, a duplicate condenser bank of Leyden jars and coil - but instead of the spark gap, there was a Geissler tube that would light up like a modern fluorescent lamp bulb when voltage was applied. There were no interconnecting wires between transmitter and receiver.

"The transformer in the transmitter group was energized from a special electric power line through an exposed two blade knife switch. When this switch was closed, the transformer grunted and groaned, the Leyden jars showed corona sizzling around their foil edges, the spark gap crackled with a noisy spark discharge, and an invisible electromagnetic field radiated energy into space from the transmitter antenna wire.

"Simultaneously, in the receiver group, the Geissler tube lighted up from radio frequency excitation picked up by the receiver antenna wire.

"Thus wireless was born. A wireless message had been transmitted by the 5 kilowatt spark transmitter, and instantly received by the Geissler tube receiver thirty feet away.

"The world famous genius who invented, conducted, and explained this lecture demonstration was Nikola Tesla."

Tesla could have signaled a greater distance, but it was only his desire to demonstrate wireless transmission and reception. Tesla's biographer John J. O'Neill wrote that all the fundamental requirements of modern radio were revealed there: 1) an antenna or aerial wire, 2) a ground connection, 3) an aerial ground circuit containing inductance and capacity, 4) adjustable inductance and capacity (for tuning), 5) sending and receiving sets tuned to resonance with each other, and 6) electronic tube detectors.

The "Geissler tube" was Tesla's electronic tube, invented in 1890, which became the first electronic tube used as a detector in a radio system. O'Neill, a Pulitzer prize winning science writer, states that Tesla's tube was the "ancestor of the detecting and amplifying tubes in use today." Tesla had previously exhibited this tube in lectures in February and March of 1892 in London at the Institute of Electrical Engineers, the Royal Society of London, and in Paris at the French Society of Physics and the International Society of Electrical Engineers. Of the device he said in these lectures: "I think it may find practical applications in telegraphy." In St. Louis he said that his mind was constantly filled with thoughts of "the transmission of intelligible signals, or, perhaps, even power, to any distance without the use of wires." He also demonstrated in the lectures of this period wireless lighting and a wireless motor.

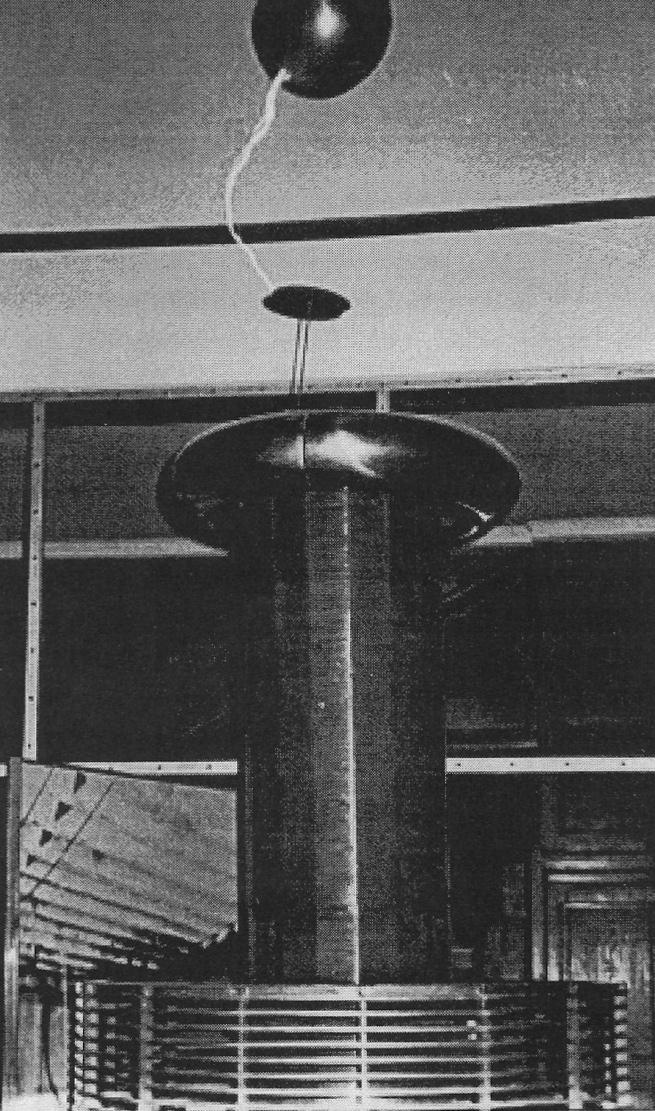

Thomas Cummerford Martin, an English physicist, was so impressed with Tesla's lectures of 1892 that he arranged to have them published in 1894. The book, The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla, has been recently reprinted by Barnes & Noble. Much of it is devoted to high frequency and high potential currents, and there is a section on Tesla's electrical oscillators. One of the most famous illustrations in this book is Fig. 165 which experts cite as evidence in support of Tesla's claim of radio invention.

For laymen, the diagram is difficult to understand, but it does show coupled resonant circuits with transformers for stepping up the voltage and frequency of currents from an ordinary dynamo or generator. This shows a way to produce high frequency currents and rapid electrical oscillations which were first found by Hertz to be required to generate radio waves. Ordinary dynamos were insufficient in this regard until Tesla showed this modification.

On page 346 of this book, Tesla proposes wireless transmission of "intelligible signals" as in the above quote. In another figure in Inventions, Fig. 185, Tesla proposes grounding an alternating current source or generator, which, connected as in Fig. 165, would provide an electromagnetic wave producing system. Spark gap dischargers can be seen in the circuits of Fig. 165. In these Tesla oscillators, the generators never shut down. They were transmitters, and Tesla had a boxed receiver which he used to carry around his neighborhood in New York checking the frequencies emitted by high frequency alternators running in his laboratory.

Between 1890-1893, Tesla's life was hectic, and there were many distractions from his wireless work. After nearly suffering a breakdown from exhaustion, he accepted invitations to deliver his famous lectures in London and Paris. From France, he proceeded to Gospic, Lika, to his mother's deathbed.

Also in 1893, he was taken away from his researches when he demonstrated alternating current and his amazing devices at the Chicago World's Fair at the request of Westinghouse, "the men whom Tesla made."

Among his World's Fair demonstrations were wireless lamps, phosphorescent bulbs and tubes, lit by radio waves generated by a Tesla oscillator transmitter. Tesla himself blew the glass and bent the tubes for the demonstration. They were shaped into the names of great scientists Tesla honored - Faraday, Maxwell, Helmholtz, Henry - and of the Serb poet Jovan Jovanovich Zmaj, whom he had translated into English (Serb World usa, Nov/Dec 1991, "The Wizard and the Dragon").

Tesla's exhibitions for Westinghouse at the World's Fair helped the latter secure the Niagara Falls hydroelectric power contract, showed the safety of alternating current, and defeated the advocates of direct current like Thomas Alva Edison and General Electric, who also sought the contract to produce power at the great falls.

The fire which completely destroyed his Fifth Avenue laboratory in New York in March of 1895 was another blow during this period. In 1896, Tesla gave up his lucrative royalty contract with Westinghouse at the latter's request and sold out for a little over $200,000. This act of generosity, to a man whom he considered his friend, contributed to Tesla's eventual downfall not only because he would be lacking funds in a few years, but also because the rumor that he was a fool began to circulate in financial circles.

It was during this crucial period of 1893-1896, when Tesla was experiencing health problems, personal losses, and financial setbacks, that Guglielmo Marconi began "his" early work on wireless telegraphy. J.P. Morgan, the biggest American financier who would be Tesla's last patron in wireless research, was a major investor in General Electric, and he, along with the more inventive men of wealth, depended considerably for their fortunes upon a "wired" civilization. Within a few short years, they would become major investors in the Marconi Wireless Company of America.

Tesla, despite his misfortunes, actually developed radio remote control during this time. After his lectures at the Royal Society in 1892, Lord Rayleigh, a famous physicist and chairman of the society, recommended to Tesla that he specialize in a single area of research in the future. Tesla failed to heed his advice. He considered the simultaneous development of wireless telegraphy and wireless power transmission to be important, and he was also engrossed in the problem of radio remote control. All the world seemed fascinated by the prospect of wireless communication, only one of Tesla's related interests.

Sir William Crookes, the English physicist to whom Tesla dedicated his London lectures of 1892, was very impressed with Tesla's work. He was quoted that year in the press as predicting that electromagnetic waves would be used for wireless communication. Sir Oliver Lodge of Oxford sent and received signals of the wireless telegraphic variety for a short distance of about 150 yards, and he is still described in radio histories as the first man to send and receive wireless signals despite Tesla's radio demonstrations of the preceding two years. Lodge, however, is properly credited with introducing variable inductance as a means of tuning the antenna circuits in his system of radio communication.

According to Marconi, in 1894, when he was twenty years old and vacationing in the Alps, he read an article on the Hertzian experiments in a journal and got the idea to use Hertzian waves for communication. He rushed to his home near Bologna and began his wireless experiments in 1895.

During that year, he supposedly grounded both the transmitter and receiver on some impulse and added the antenna or vertical wire insulated from the earth. When Marconi went to London to sell "his idea," he had a Hertzian transmitter with the Lodge variable inductance tuning of the antenna circuit. In addition, Marconi had ground connections and antenna as first described by Tesla in his widely published lectures of 1892/3 and a Branly coherer used as the detector at the receiver.

The coherer invented by Edouard Branly in 1890 was a tube of metal filings whose direct current conductivity was increased after exposure to weak, high frequency alternating currents as produced by radio waves. Used as a detector of radio waves in the receiver, it made possible the reproduction of a series of dots and dashes carried by radio waves as direct current pulses, which could operate a telegraph sounder.

In England on June 2, 1896, Marconi took out the first patent ever granted for wireless telegraphy by means of Hertzian waves. Marconi's mother was Irish, and he came from a wealthy aristocratic family through which he had no difficulty in making contacts in high circles. In that same year he demonstrated his invention for the British Post Office, Foreign Government Department, and British army and navy officials.

In July of 1897, after Marconi had demonstrated his invention to the king and queen of Italy and the Italian navy, a British company called the Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company, Ltd. was formed. It acquired the rights to the Marconi patent in all countries except Italy. In 1900, its name was changed to the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, Ltd. The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America was formed shortly thereafter, and both the British and American companies became hot investments in the stock markets.

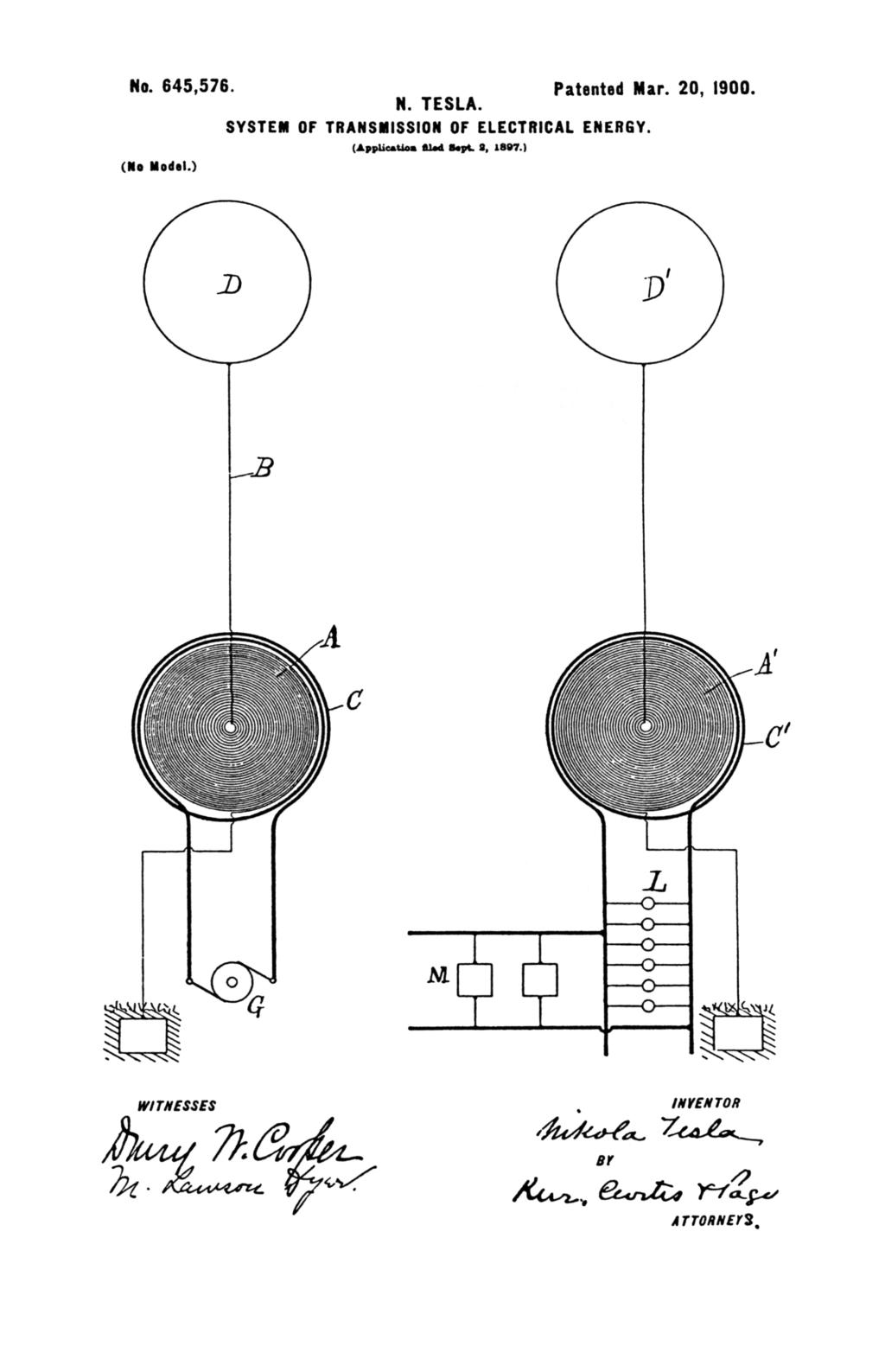

In 1897 and afterwards, as Marconi set up longer and longer distance signaling demonstrations, he apparently used the "Tesla oscillator," which, in contrast to the weak "Hertzian oscillator," had powerful radio wave propagation due to high frequency, high voltage transformers. Marconi's original British patent had only a two circuit system as did the system he attempted to patent in the United States at the turn of the century. With this device, one could not transmit across a large pond, not to mention the Atlantic Ocean, and the actual systems that he used for long distance signaling employed four tuned circuits first demonstrated by Tesla and clearly diagrammed in Tesla's 1897 patent application for No. 645,576, his most famous radio related design, which was patented in the U.S. long before Marconi actually received an American patent.

It was on September 2, 1897, that Tesla applied for this patent showing a four circuit system with two circuits each at the transmitter and the receiver and recommending that all four circuits be tuned to the same frequency. This most radio like of Tesla's patents - and, by expert definition, definitely radio - is entitled "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy." This Tesla patent, No. 645,576, was allowed on March 20, 1900. Only several months later did Marconi file his first application for American patent No. 763,772 on November 10, 1900.

Marconi's first application for patent was turned down on the basis of the prior art of Lodge. Marconi's subsequent revised applications were rejected by the patent examiner repeatedly for three more years on the basis of the priority of Tesla, Lodge, and Braun.

When called before the Commissioner on Patents by a petition from Marconi to revive his patent application, the examiner recommended that the petition for revival be denied and wrote:

"Many of the claims are not patentable over Tesla #645,576 and 649,621, of record, the amendment to overcome said references as well as Marconi's pretended ignorance of the nature of a ‘Tesla oscillator' being little short of absurd. Ever since Tesla's famous lecture on alternating current of high frequency delivered before the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in 1891 and repeated in 1892 before the Institute of Electrical Engineers and the Royal Institution, London, the Societe Internationale des Electricians, and the Societe Francaise de Physique, Paris, which lectures have been widely published in all languages, the term ‘Tesla oscillator' has become a household word on both continents."

The examiner further alleged that Marconi knew of it and had used it, because he had been quoted by Della Rictia in an 1898 publication as having used the Tesla oscillator at least as early as 1897.

In 1904 there was a sudden and surprising reversal. The Commissioner on Patents granted a reconsideration, and a different examiner almost immediately granted Marconi his American patent on June 28, 1904.

Much of Tesla's prototype equipment and notes for radio development were lost in his New York lab fire of March, 1896, but he did transmit signals from a boat on the Hudson River to a point twenty-five miles distant in 1897, the same year in which Marconi's best was eight miles.

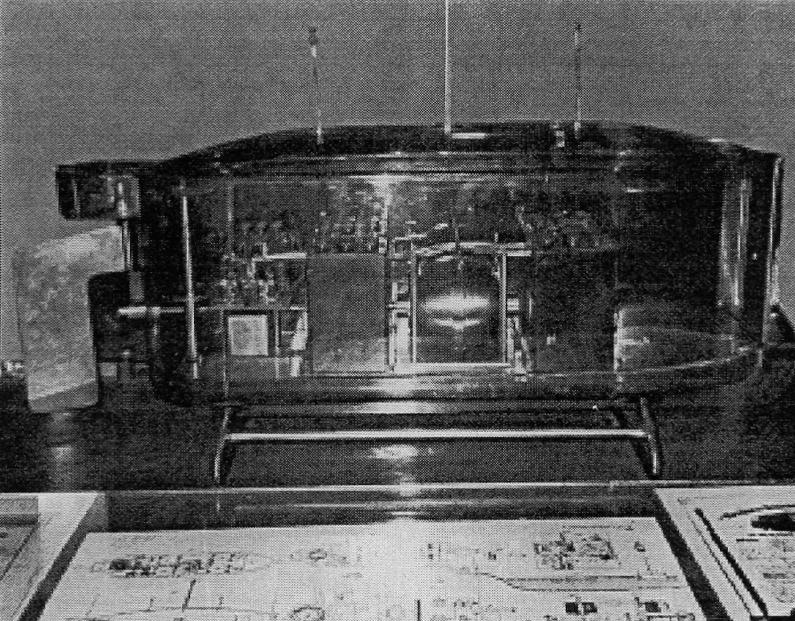

Tesla wrote that, in 1899, he had radioed signals six hundred miles from his Colorado Springs laboratory. He had gone to Colorado that year to work on electrical transmission, and much of his work there was the construction of a super transmitter. He had selected the location because of its high altitude and the presence of large electric power companies which supplied the numerous mines in the vicinity.

While in the Colorado resort town, which was something of an Aspen of its day, he blew out the generator of the Colorado Springs Electric Company, a very bad publicity accident that would contribute to his image as a "mad scientist." The publicity photographs he himself had prepared there, showing him seated in the midst of electric streamer discharges, backfired. They were intended to show him as the "wizard of electricity," which he was, an image he had cultivated since the Chicago World's Fair days, but, combined with the power blowout - whose news was brought by the wealthy vacationers back to the East - the photos only added to his rivals' portrayal of him as a dangerous fool.

In addition, while in Colorado, with his sensitive radio receiver, he became the first to detect and recognize radio pulses from outer space. His speculation that they might be messages from extraterrestrials was played up by the press as further proof of his "madness." The sensational images of the prophet of high voltage with "lightning in his hands," hearing voices from outer space while blowing out the city power, completely covered over his experiments in transmission and reception, which were more advanced than any in that day.

As a result, he lost credibility with potential patrons for supporting his research. Although he became convinced that he must devote himself almost exclusively to radio development, the investors here and abroad were placing their money on Marconi, who as a handsome, young, aristocratic genius had captured the hearts of the press and the purse strings of high finance. At this crucial time of 1900, Westinghouse himself turned down the financial requests of Tesla, the "man who made Westinghouse," and advised him to seek capital from other financiers.

In 1900 the stock of the British Marconi company was selling at $22, seven times its original offering of $3 just three years before. The press promotion of Marconi did not hurt. Thomas Edison and Andrew Carnegie endorsed the Marconi system, and Thomas Edison and Michael Pupin were listed as consulting engineers of the American Marconi company, whose stock was also skyrocketing.

In 1900 Tesla approached the biggest financier of the time, J.P. Morgan, with a plan to construct a worldwide broadcasting system. Tesla had been preoccupied with the "wireless transmission of power" since 1893 and could not separate this project from the development of "wireless communication." He still hoped to achieve both simultaneously, but he said nothing about "wireless power" to Morgan, who had "wired power" investments in both General Electric and Westinghouse power companies. Morgan agreed to finance Tesla's wireless communication project to the limited extent of $160,000, not all forth coming at once.

Tesla had fatally allowed Marconi and his investors to get a big head start on him. Marconi now had an army of engineers working with him. Looking back, the question of what Tesla was doing during the period of 1896-1900 becomes inevitable.

In 1896 he had to rebuild his laboratory, and his Colorado research occupied much of 1899, but 1898 was an exceptional year indeed. That year marked the culmination of his radio remote control projects, covered by patent No. 613,809 and entitled "Method of and Apparatus for Controlling Mechanism of Moving Vessels and Vehicles."

Tesla offered this wondrous invention and application to the U.S. government, because he thought that the U.S. Navy would be especially interested in it. Ironically, the official with whom he spoke apparently thought the idea was incredible. The patent official required an actual demonstration of a working model before he believed it. Between 1895 and 1898 the development of this radio remote control, which Tesla called "teleautomatics" (distant robotics), had occupied much of his time.

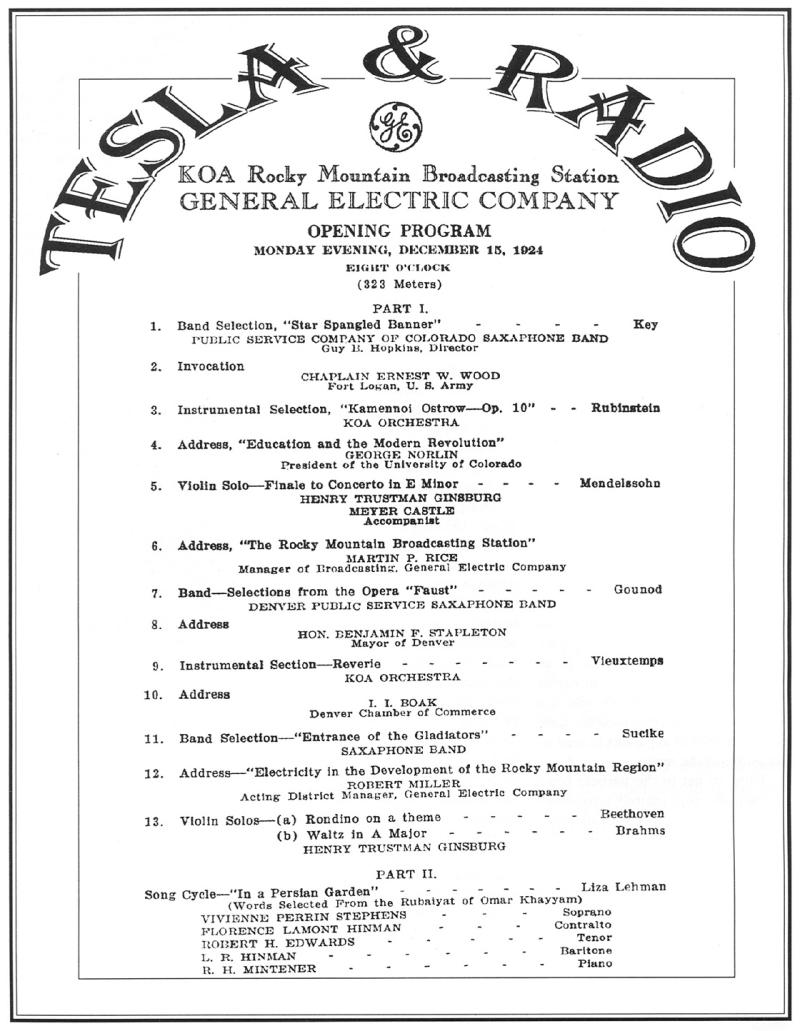

With the limited capital advanced to him by Morgan, Tesla purchased land on Long Island and began to erect the Wardenclyffe Tower between 1901 and 1903. His plan for a worldwide radio system anticipated all the features of modern broadcasting, which did not begin until about 1920just after the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) took over the American Marconi company in 1919 and began its broadcasts.

Tesla moved his lab to Long Island's Wardenclyffe where his work toward a world broadcasting system was never completed due to insufficient funding. J.P. Morgan refused to advance any more money after July 3, 1903.

A few months before, in February of 1903, an article in Electrical Age described Tesla as a man who had not fulfilled his earlier promise as the most brilliant electrical engineer. This adverse publicity helped to sink his star at the same time the glowing press of Marconi and company brought investment capital, research engineers, and lawyers into their fold.

In 1901, after Marconi's successful trans-Atlantic signal, Otis Pond, a fellow engineer in Tesla's employ at Wardenclyffe, remarked to the great inventor: "Looks like Marconi got the jump on you."

Tesla replied: "Marconi is a good fellow. Let him continue. He is using seventeen of my patents."

The decade of 1900-1910 was marked by more than one general economic depression, and funds were scarce. In 1906, as Tesla turned fifty, he patented a bladeless turbine which he hoped would ease his strapped circumstances, but other turbines and established firms were entrenched. Interest in this turbine has only been renewed recently.

In 1909 Marconi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics along with Karl Braun of Germany. In 1915 it was rumored in the press - and never denied by the Nobel selection committee - that Tesla and Edison would be the first choices to share the physics prize, but the award went instead to W.H. Bragg and his son for their work in x-ray crystallography. The full story of what took place is unknown. O'Neill wrote that Tesla refused to share the award with Edison while others have said the reverse. Certainly Edison and his investment colleagues were part of the nemesis of Tesla.

Wireless a la Marconi had become one of the most attractive investments, and a "Marconi Affair" with American repercussions almost toppled the Lloyd George government of Great Britain in 1912. In June of 1911, the Imperial Defense Committee declared that the installation of wireless communication throughout the British Empire was an emergency, and the Post Master General Herbert Samuel began to negotiate with Godfrey Isaacs, the managing director of the English Marconi company, for the erection of a network of wireless stations. Isaacs' brother, Rufus, was the Attorney General in the Lloyd George government.

A month after the first tentative agreement between the government and the company was reached, Liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George and Arthur Murray, the Chief Liberal Whip in Parliament, each purchased 1,000 shares in the American Marconi company from their friend, Attorney General Rufus Isaacs. Rufus Isaacs had bought 10,000 shares of stock from his brother Godfrey though it was not yet on the open market. Lloyd George sold his shares quickly for a profit of nearly a thousand pounds and then bought 3,000 more on credit for himself and Murray.

The uncovering of this "Marconi Episode" by the opposition and the press led to a select committee of investigation and a motion to censure Lloyd George and his associates. The motion barely failed passage in 1913.

In 1915, while Wardenclyffe was falling into the hands of Tesla's creditors - including Westinghouse, Tesla received a contract from a German firm to use his radio patents and set up a transmitter on the New Jersey coast. When they told Tesla that they had successfully transmitted 9,000 miles, he replied that he had done that as early as 1899 with his Colorado transmitter.

It was at this difficult time in his life with his laboratory at Wardenclyffe being seized for debts that Tesla began publicly to proclaim, in press statements and articles, priority in the invention of the radio. A New York Times article of August 4, 1915, bore the headline: "TESLA SUES MARCONI ON WIRELESS PATENT: Alleges that Important Apparatus Infringes Prior Rights Granted to Him."

Although he was financially unable to pursue his case, his complaint was noted by the federal government's defense when the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America sued the U.S. Court of Claims for about $43,000 on July 29, 1916, alleging that the U.S., in this time of World War I, had used wireless signaling equipment, which infringed on Marconi's patent No. 763,772.

The Marconi company did not need the money but wanted to serve notice to the government and its armed services that they could not use its 1904 patented devices as though they were "free to the world." The American Marconi company wanted government contracts such as they had secured with the British government.

An exceptional source on this subsequently famous affair is Leland I. Anderson's monograph: "Priority in the Invention of Radio: Tesla vs. Marconi" which contains an excellent and precise extract of the U.S. Supreme Court decision of 1943 which invalidated the fundamental radio patents of Marconi" and gave Tesla and others the recognition in priority that they deserved. Another is a 1992 Leland Anderson edited book Nikola Tesla on His Work with Alternating currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy; Telephony and Transmission of Power: An Extended Interview. The book - to which K.L Corum and J.F. Corum also contributed - is written as an interview of 60 year old Tesla, the age he was in 1916, by an attorney. It ties together his radio work, oscillators, high frequency alternators, Colorado experiments, and more in what is the technical and legal case for Tesla. It is well illustrated and compares the apparatus and patents of Tesla and Marconi.

The case of Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America vs. The U.S. took many years to reach the U.S. Supreme Court whose decision came 27 years after the suit was launched. In the meantime, the Marconi company had become part of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which continued the suit under the old name. At the end of his monograph, Anderson summarizes the findings of the court in the case which was in a large part "Tesla vs. Marconi:"

"In summary, the Court found that Tesla, in patent #645,576, applied for September 2, 1897, and allowed March 20, 1900, anticipated the following features of the Marconi patent: a) a charging circuit in the transmitter for causing oscillations of the desired frequency, coupled, through a transformer, with the open antenna circuit, and b) the synchronization of the two circuits by the proper disposition of the inductance in either the closed or antenna circuit or both."

The report went on to say "By this and the added disclosure of the two circuit arrangement in the receiver with similar adjustment, he anticipated the four circuit tuned combination of Marconi."

Marconi himself had probably invented no one specific component of the radio system attributed to him, but, as he modestly told his British audience in his early English demonstrations of 1896, he had put together the devices of others not the least of which were those of Nikola Tesla.

Justice Frank further wrote a dissenting opinion praising the synthesizing ability and determination of Marconi. In addition to the work of Tesla, Lodge and others cited in the decision as having priority over Marconi in the development of wireless, the radio pioneer John S. Stone's work is repeatedly noted.

John Stone had mathematically described the operations of four tuned coupled circuits and made improvements in early radio transmission by emphasizing the fine tuning of the antenna circuits. Anderson closes his classic monograph with a quotation from Stone which pays the greatest tribute to Tesla:

"Among all...the name of Nikola Tesla stands out most prominently. Tesla, with his almost preternatural insight into alternating current phenomena that has enabled him some years before to revolutionize the art of electric power transmission through the invention of the rotary field motor, knew how to make resonance serve, not merely the role of microscope, to make visible the electric oscillations, as Hertz had done, but he made it serve the role of stereopticon...He did more to excite interest and create an intelligent understanding of these phenomena...than anyone else...and it has been difficult to make any but unimportant improvements in the art of radio telegraphy without traveling, part of the way at least, along a trail blazed by this pioneer who, though eminently ingenious, practical, and successful in apparatus he devised and constructed, was so far ahead of his time that the best of us then mistook him for a dreamer."

All of this statement is important, especially with regard to wireless telegraphy or radio, because it was made by a radio expert and pioneer himself. Today - many, many years later - the situation has not changed except legalistically and technically speaking. Tesla and his work are a vital part of American scientific history, but apparently other voices - both expert and interested - have persisted for decades.

Major General Joseph O. Mauborgne, former commander of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, testified in the famous U.S. Supreme Court case that Tesla: "...appreciated the necessity of synchronism and he taught the use of coupled circuits long before Marconi or Lodge." Mauborgne also wrote in the February 1943 Radio Electronics Magazine just after Tesla's death:

"Tesla ‘the wizard'... captured the imagination of my generation with his flights of fancy into the unknown realms of space and electricity...(and saw) with astounding vision far beyond his contemporaries, very few of whom realized until many years after the work of Marconi that the great Tesla was the first to work out not only the principles of electric tuning or resonance, but actually designed a system of wireless transmission of intelligence in the year 1893."

Those who followed the court case have been surpassed time and time again by the apparent failure of the information to penetrate into both the professional and popular history of radio.

For example, ham radio expert Richard Kovich (SWusa, Jul/Aug 1994) recalls an incident from his training to be a U.S. Navy radio operator during World War II: "...one of our (radio) theory instructors, a woman who was a ham and an assistant professor of electrical engineering, gave a talk on the development of radio with extensive reference to Marconi...

"Politely, but firmly, I informed her that the United States Supreme Court had declared most of the late Marconi's radio patents invalid. She stared at me for what appeared to be an eternity...

"Without an immediate reply, I worked for a few days, and then she did announce to our class that the court indeed had made a decision not in favor of Marconi. I have no idea where I learned about the court case but most likely from radio magazines or the Serb National Federation's Serbobran or the Croatian Fraternal Union's Zajednicar, both of which Nikola Maras, a Croatian neighbor, gave to Mother for her to read to him."

The December 1995 issue of Amateur Radio Today contained a powerful article entitled "Nikola Tesla, the First Radio Amateur and the Real Inventor of Radio" by John Wagner. He tells how a bust of Tesla, commissioned by his students, was rejected by a curator of the Smithsonian Institution even though there was no recognition of Tesla in its electrical history exhibits, and though his alternating current, induction motor was displayed alongside a bust of Edison.

A provocative note is appended to the Wagner article on Tesla:

"Tesla was, in my estimation, the single greatest genius in history. In addition to inventing electricity as we know it and laying the groundwork for radio, Tesla also invented the electric clock, the loud speaker, the fluorescent lamp, and a long list of other firsts. At a time when the text books were claiming that voice could never be transmitted by radio, Tesla was planning a world radio broadcasting system, and was building a tower on Long Island to transmit free electric power. The electric companies, seeing this as a serious threat to their making and selling electricity, got together and put Tesla out of business. Please help put pressure on the Smithsonian to recognize this incredible genius."

It is difficult to prove just exactly who was responsible for the shutdown of Tesla at Wardenclyffe, but Morgan, who owned a large share of the stock of General Electric, did curtail his financial support of Tesla when he was working on the world broadcasting system. Desperate for funds in the summer of 1903, Tesla wrote to Morgan on July 3rd and revealed to the financier, in one last request for financing, that he not only planned radio broadcasting but also the wireless transmission of power. Morgan wrote to Tesla for the last time saying: "...I should not feel disposed at present to make any further advances."

In attempting to make their case for Marconi, the radio corporation lawyers claimed that Tesla's patents were for wireless power transmission and not signal communication. Their argument eventually failed.

In his monograph, Leland Anderson made an interesting table of Tesla transmitting patents which reveals that nine of the twelve had signalling specifications, while five of the nine signalling patents also had power transmission specifications. It seems, in retrospect, that, if Tesla had not insisted on simultaneously developing wireless communication and wireless power transmission, he might have received the necessary financing to complete the first world broadcasting system.

How does one answer the question: Did Marconi or Tesla invent the radio? Marconi did not invent the radio, but Marconi and the Marconi companies did develop the radio systems of the world. The radios or wireless telegraphs they used to accomplish this were, however, the inventions of Tesla, Lodge, Stone and others, and, as Stone himself wrote, Tesla's contributions were greatest.

Tesla's demonstrations of radio signaling in 1892/93 predated Marconi's first attempts by at least two years, and it was undoubtedly Tesla's public statements about the potential for wireless communication that led all others to become involved in the field. It is much more difficult to answer the question: Why does Marconi continue to receive credit for the invention of the radio while Tesla does not?

Fortunately, there is a Tesla revival currently underway. Hopefully, it will be difficult for young people one day to believe that there was a long period of time during which Tesla was nearly forgotten. Credit for this is due the scientific community and science writers who have continued research and publishing, often at their own expense and with small publishing houses, in the interest of bringing to light the genius of Nikola Tesla to whom the world owes so much.

Remembering Tesla and his work is important for not only Serbian-Americans but for all Americans.

This article is reprinted in its entirety with great thanks and with the kind permission of Serb World U.S.A. 415 E. Mabel St., Tucson, AZ 85705, Mary Hart, Editor.