Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's Electrical Discoveries

At the recent meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Nikola Tesla, of Columbia College, New York, described and illustrated in a lecture some of the most remarkable discoveries in the field of electricity that have been made public since the inauguration of the modern electrical era by Bell, Thomson and Edison.

Mr. Tesla's discoveries relate to the utilization of alternating currents; but his work has carried him far beyond the limits set by Lodge and Hertz, the exponents of the electro-magnetic theory of light, and he appears to-day as the discoverer of phenomena so novel and revolutionary as to have absolutely no rivals in the field, and to have cut out for himself a path in a field of observation in which he stands alone. It appears, from what we know of Tesla's work at this writing, as though his discoveries had thrown a beam of light so far into the darkness which has hitherto obscured the vision of science, that the near future may reveal applications of the most novel and astonishing nature in connection with the production of light by electric method; so original, in fact, that the present methods of electric lighting, scarcely a decade old, may be entirely superseded by others bearing no relation to them in general principle.

The results exhibited by Mr. Tesla in his remarkable lecture, were made in connection with his study of the phenomena presented by alternating currents. But instead of contenting himself with repeating the experimental work of his predecessors in this field, by operating upon currents interrupted a few hundred times per second, he devised apparatus by which these alternations could be enormously increased, and thus, at a step, disclosed phenomena so remarkable as to warrant the statement that his discoveries are simply revolutionary.

It is difficult to give, in the brief space at our disposal, a lucid statement of Tesla's discoveries, since they involve phenomena of whose relationships we at present know so little. Nevertheless, we will endeavor in the following to present his most interesting conclusions as clearly as may be, by following his footsteps in the series of experiments he presented in his lecture.

He began with the induction coil, an electrical apparatus well known to every student of electricity, and with which electric sparks may readily be obtained when it is operated by currents which are, by automatic devices of various kinds, interrupted. In common practice with such machines, they are operated by currents that are interrupted but a few times a second, or by what are called alternating currents — alternating, say, from 100 to 200 times a second.

In the study of the phenomena of such interrupted currents, Tesla reasoned that if he could interrupt, or alternate, the current at a much higher rate per second, the effects produced might thereby be correspondingly enhanced; and in order to determine whether this inference was correct, he devised an apparatus whereby he was enabled to obtain as many as 20,000 alternations per second. With this machine he was able to satisfy himself that his theoretical views were correct. An obvious proof of this was afforded by the quality of the spark, or electric discharge, obtained between the terminals of the induction machine when currents alternated with such high frequency were employed. He was enabled to distinguish, in fact, no less than five different forms of discharge, according to the rate of the alternations, from a thin thread-like discharge, to something totally different, and which can only be compared to a hot flame streaming forth from the terminal.

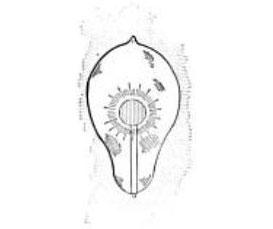

Of the great number of extremely interesting phenomena observed by Tesla in the course of his experiments with these currents of extremely high rates of alternation, we have selected a few of the more striking only to give our leaders an approximate idea of their remarkable character. Fig. 1 exhibits an ordinary induction coil, having a wire attached to one of the terminals. With the rapidly alternating currents streams of light are observed to issue not only from the end of the wire, but from all sides throughout its length, illustrating in a remarkable manner the intensity of the actions that are taking place. Fig. 2 represents a similar induction machine, upon one terminal of which a glass globe Is placed, within which is a platinum wire. The application of Tesla's current causes this fine thread to become intensely luminous, and to spin around in the globe with such velocity as to resemble an illuminated funnel. Upon this phenomena Tesla has based the electric lamp seen in Fig. 3, consisting simply of an exhausted glass globe containing a button of some refractory material attached to the end of a wire conducting the current into the globe. A lamp of this kind, with only a single wire, gives out a blight light; and he further determined the singular fact that the leading-in wire was not necessary, and that such a lamp would be made to glow without it.

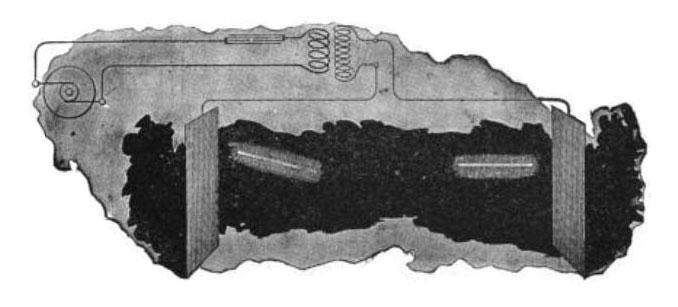

He has gone even further than this, and has actually demonstrated by experiment, that, by proper adaptation of his discoveries, a lamp can be constructed that can be made to give light without having any outside connection whatever, and anywhere in a room where proper disposition of his apparatus is made. The diagram shown in Fig. 4 exhibits the arrangement of his system of apparatus for accomplishing this extraordinary result. In this, A is the dynamo, placed at the central station, with wires leading to the places where light is required. Here a condenser C is placed in the circuit, and close to it an induction coil B, by which last the low potential currents of the dynamo are converted to those of the very high potential required by his system. In the apartment to be lighted, two sheets of metal are placed on the opposite walls, or, in lieu of these, a metallic wall paper may be utilized for the same purpose. With an arrangement like that just described, the exhausted glass tubes T T, without wires or other outside connections of any description, become highly luminous within the room, and can be moved about freely from place to place like an ordinary hand lamp.

The most striking illustration of the difference between the effects produced by the alternating currents with which we have heretofore been familiar and those of enormously higher frequency employed by Tesla, is shown by Fig. 5. This is a lamp supplied with a carbon filament, similar to that employed in the ordinary incandescent lamps; and it will be perceived that when this is brought into the apartment affected by the Tesla currents, the whole interior of the glass globe becomes highly luminous, while the carbon remains dark.

The phenomenon of the hot flame above referred to, and shown in Fig. 6, is a most interesting one, and would appear to open up quite new fields of application. This flame is merely that of the electric discharge, and does not indicate combustion of any kind.

We have thus Indicated in the most brief and cursory manner the leading elements of these remarkable experiments, which, in the judgment of the most advanced electricians, signalize the advent of a new era in electric lighting, and have opened the door upon some of nature's most curious and important mysteries, which may lead us, we can hardly even speculate, where.