Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's spirit lives on in Springs

Dayspring Academy teacher a true believer

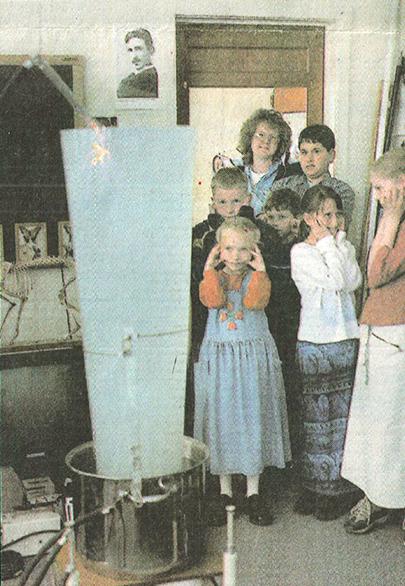

With the flick of a switch, a low hum starts to spread around the cluttered science classroom at Dayspring Academy in Old Colorado City. The sound is coming from a large glass vat sitting in a pan of water and hooked up to a 7,000-8,000-volt transformer.

Soon, tiny sparks leap out of the top of the glass, and the low hum becomes a loud crackle. Eventually, the sparks grow into small bolts of lightning, and the young students at Dayspring cover their ears.

This demonstration is certainly dramatic, but it's pretty standard fare if you're a student of Mike McKee, an eccentric devotee of Nikola Tesla who teaches science at Dayspring.

Tesla, (1856-1943) a brilliant or crazy inventor depending on your point of view, brought alternating current into the mainstream and pioneered technology that led to radio.

TESLA: Fan says cover-up hides truth

Although born in Croatia, Tesla spent most of his life in America. For a while, he haunted a laboratory in Colorado Springs, where he tapped a free power supply courtesy of the fledgling Colorado Springs Electric Co. One of his experiments with power transmission famously touched off a citywide blackout in 1899. The stunt didn't earn him any friends, and he soon moved back to New York.

Some of Tesla's followers raise eyebrows in the mainstream scientific community, but Tesla himself commands respect.

"There's no question that he was a genius," says Ted Lindeman, a chemistry professor at Colorado College. "He was the super-duper pioneer, as far as I can tell, on alternating current. Nobody understood that any better than Tesla."

FOR MORE

For a group demonstration of Tesla gadgets, leave a message at 222-1911.

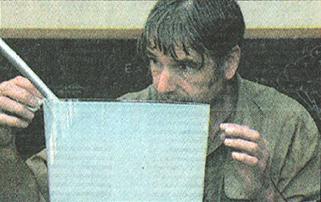

McKee's classroom, which doubles as an informal museum for any interested student group, is crammed to the gills with all kinds of electronic and Tesla-inspired gadgets that he has collected or made over the years. There's a collection of antique flashlights, all kinds of light bulbs, and an entire table devoted to vacuum tubes. On a low shelf, there's even a book of declassified FBI documents that McKee says spotlight the government's efforts to suppress Tesla's work.

McKee is especially proud of his collection of Tesla coils — transformers that essentially broadcast electrical energy at short distances. Most are about the size of a small paperback book. But one, in the corner of the room, nearly reaches the ceiling.

McKee has a little device on his window sill that he says will start an earthquake. He also claims to have a working death ray, something Tesla worked on but which never made it into the Pentagon's arsenal. McKee shies away from a live demonstration of either gadget but insists he can and will give them a whirl eventually.

McKee's ideas aren't all that uncommon in the community of Tesla junkies, but they don't pass muster with mainstream science.

"They certainly are enthusiastic," Colorado College's Lindeman says of the Tesla crowd. "If it were true that you could do with energy what some of them believe that you can that would be quite exciting indeed."

"These sorts of enthusiasms aren't focused only around Tesla," Lindeman adds, recalling cold fusion and cars that supposedly run on water alone. "Maybe it's just a dream programmed into people."

Or maybe somebody out there doesn't want you to know.

"There was a conspiracy not to mention Tesla, even by the military," McKee says. The reason: They are deathly afraid people's curiosity would pique, leading to scientific research that would put the power companies out of business, he says.

"In Tesla coils, there's a secret to a lot of things. Free energy is possible."

Lindeman counters: "I fear these phrases get embraced by enthusiasts who don't know the science."

All quibbling aside, McKee's classroom is the last place in Colorado Springs dedicated to Tesla-inspired gadgets and experiments, after the bankruptcy-induced closure of the Tesla Museum of Science and Industry in 1999. The artifacts from the museum are missing, much to the chagrin of the museum's creditors.

McKee says he doesn't know anything about those museum pieces. Besides, he adds, "my stuff is more powerful than their stuff."