Plans

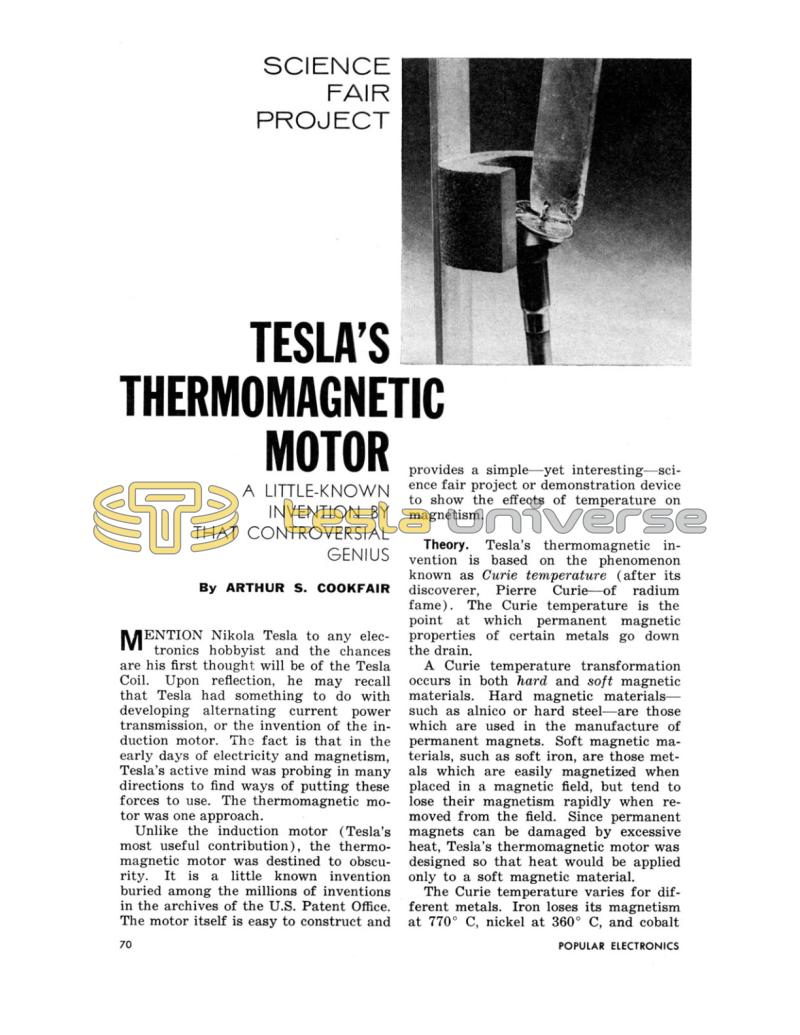

Tesla's Thermomagnetic Motor

A Little-Known Invention By That Controversial Genius

Mention Nikola Tesla to any electronics hobbyist and the chances are his first thought will be of the Tesla Coil. Upon reflection, he may recall that Tesla had something to do with developing alternating current power transmission, or the invention of the induction motor. The fact is that in the early days of electricity and magnetism, Tesla's active mind was probing in many directions to find ways of putting these forces to use. The thermomagnetic motor was one approach.

Unlike the induction motor (Tesla's most useful contribution), the thermomagnetic motor was destined to obscurity. It is a little known invention buried among the millions of inventions in the archives of the U.S. Patent Office. The motor itself is easy to construct and provides a simple — yet interesting — science fair project or demonstration device to show the effects of temperature on magnetism.

Theory. Tesla's thermomagnetic invention is based on the phenomenon known as Curie temperature (after its discoverer, Pierre Curie — of radium fame). The Curie temperature is the point at which permanent magnetic properties of certain metals go down the drain.

A Curie temperature transformation occurs in both hard and soft magnetic materials. Hard magnetic materials — such as alnico or hard steel — are those which are used in the manufacture of permanent magnets. Soft magnetic materials, such as soft iron, are those metals which are easily magnetized when placed in a magnetic field, but tend to lose their magnetism rapidly when removed from the field. Since permanent magnets can be damaged by excessive heat, Tesla's thermomagnetic motor was designed so that heat would be applied only to a soft magnetic material.

The Curie temperature varies for different metals. Iron loses its magnetism at 770° C, nickel at 360° C, and cobalt at 1120° C. Alloys such as nickel-iron may lose their magnetism at temperatures ranging from below room temperature as high as 770° C, depending on the ratio of nickel to iron. Place any one of the above metals or alloys near a magnet, at ordinary temperatures, and it will be attracted. Heat it above the Curie temperature and the attraction is lost. As it cools, the magnetic attraction returns. Alternate heating and cooling creates an alternating magnetic force.

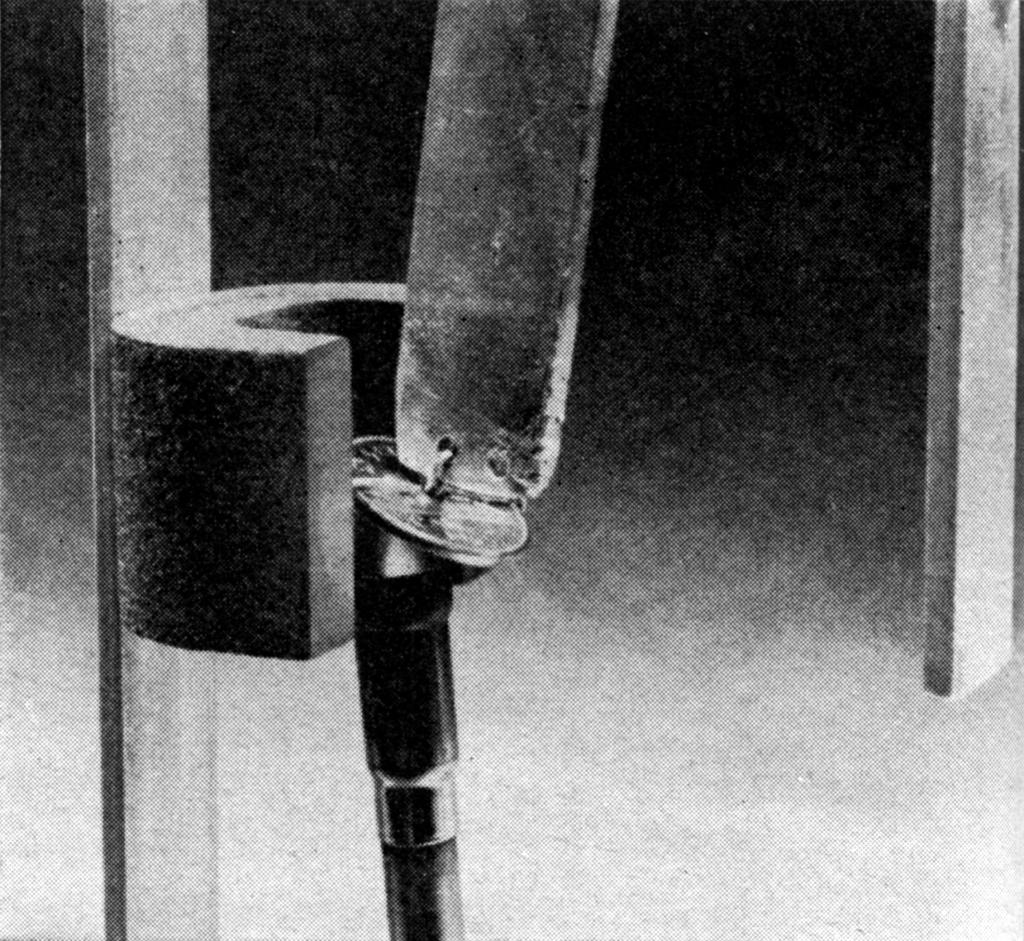

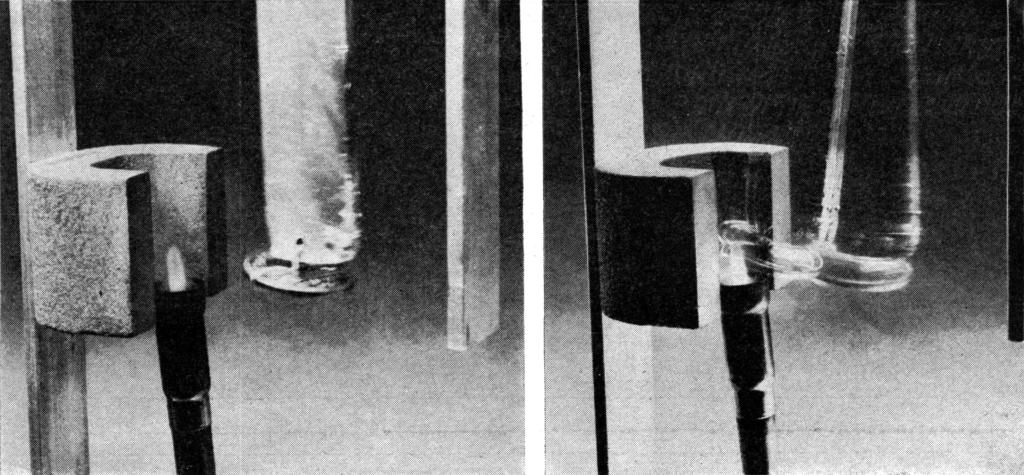

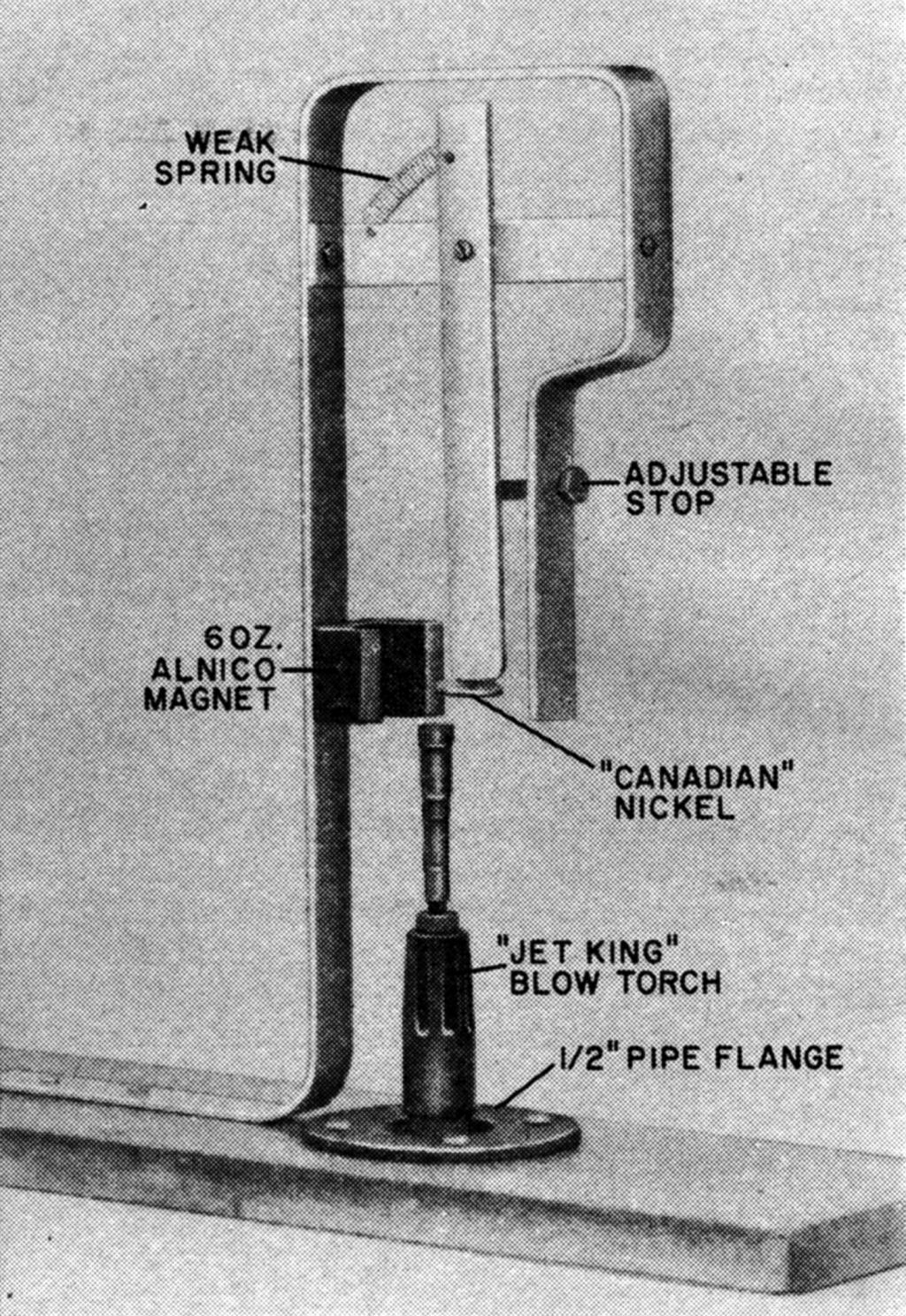

How It Works. In operation, a facsimile of Tesla's motor consists of a movable rider made of a soft magnetic material that is pulled in one direction by a spring and in the opposite direction by a magnet — the magnet being the stronger of the two forces. The rider is pulled by the magnet to a position where it can be heated by a flame (or other heat source).

When the rider reaches the Curie temperature, it is no longer attracted by the magnet and is pulled away from the flame by the spring. The rider cools rapidly to below the Curie temperature, regains its magnetic properties, is again attracted by the magnet to a position over the flame; and the cycle repeats itself.

The frequency of the rider oscillation depends on the heating and cooling cycle. Once the operation has started, the magnetic rider will remain close to the Curie transformation point and will lose and regain its magnetic properties by variations of only a few degrees above or below that temperature.

A Bunsen burner or hand propane torch will do an excellent job of heating. If these are not available, a candle will serve the purpose. Or, if you want to keep up with the latest trends in science, you can demonstrate the conversion of solar energy by heating the rider with a small magnifying glass.

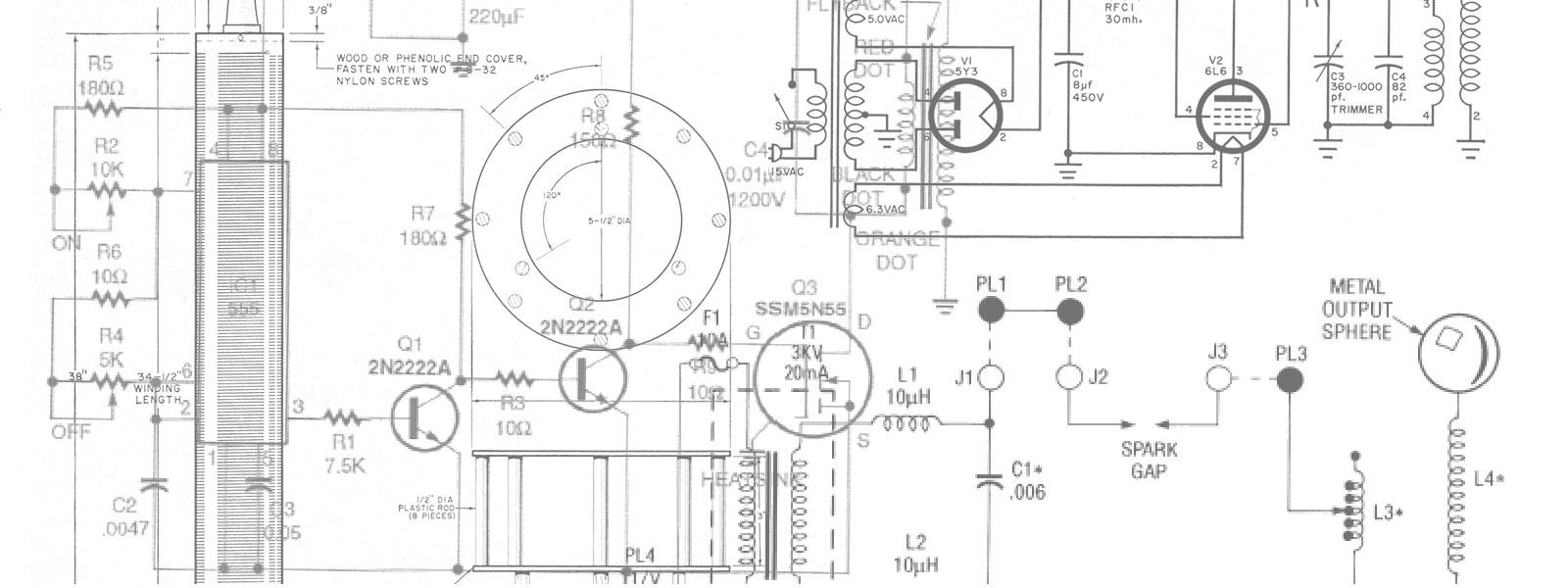

Construction. The frame of the motor shown (above and on page 114) was made of aluminum since it is easy to work and the non-magnetic qualities of aluminum will not be attracted by the magnetic field. You can build the motor to operate with almost any size of magnet. Small alnico magnets are available in hardware stores. Naturally, a more powerful magnet is easier to use — it will pull from a greater distance, and it also permits the use of a heavier spring. In a model similar to that shown, a 2-ounce alnico magnet, purchased at the local hardware store for $1.25, served the purpose admirably.

Almost any magnetic material can be used for the magnetic rider. Iron is an obvious choice because of its availability (nails, paper clips, and a host of other common items). However, nickel is better since it has a much lower Curie temperature. But don't bother trying to use United States nickels — they are made of a non-magnetic nickel-copper alloy. However, Canadian nickels are quite magnetic and will work very well.

A limitless number of variations of the basic thermomagnetic motor can be devised. A few of Nikola Tesla's variations can be seen in his patent drawings. Tesla was granted two patents (numbers 396,121 and 428,057) for his invention of the thermomagnetic motor, copies of which can be obtained for 50 cents each from the Commissioner of Patents, Washington, D.C.