Nikola Tesla Articles

Powerful Turbine a Mere Toy

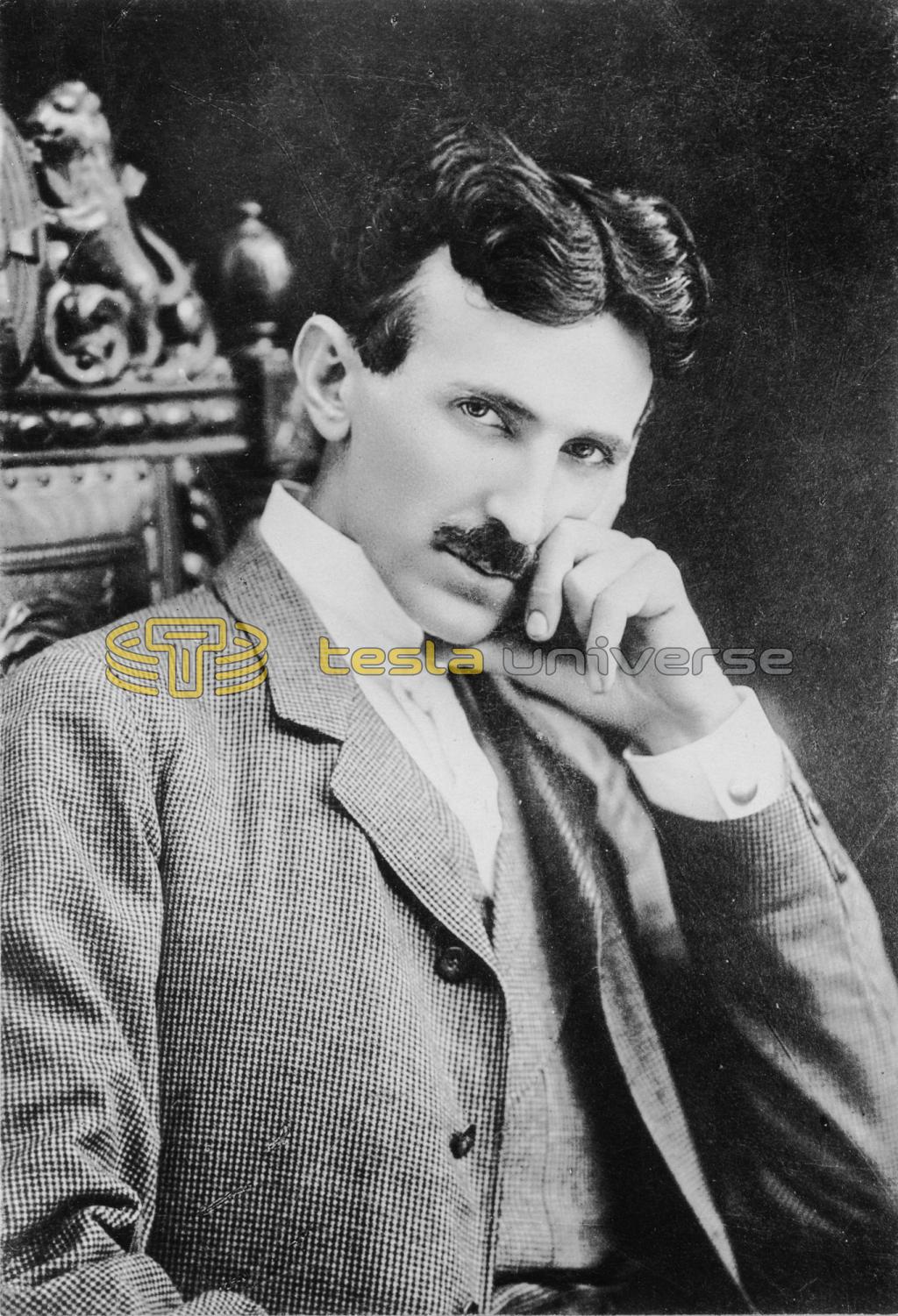

Almost any evening last fall a tall, spare man, whose discouraged looking mustache remains a glossy black without any aid from the barber in spite of the fact that its wearer is well past his fiftieth year, might have been seen wending his dignified way down East Thirty-eighth Street toward First Avenue, New York City. He was a man who would attract attention anywhere, but especially on East Thirty-eighth Street, which is not a thoroughfare one would choose for an evening stroll, unless one chanced to be hard up for strolls. If the tall man had been shadowed he would have been seen invariably to disappear within a massive brick building which covers the entire block between Thirty-eighth and Thirty-ninth streets, First Avenue and that part of Long Island Sound miscalled "East River".

Had the phenomenon been further investigated, this building would have been found to be a place of extraordinary interest, for various reasons. Together with its twin covering, the next block north, it constitutes the Waterside Station of the New York Edison Company, the largest steam power plant in the world. Of still greater interest than its size is the fact that ever since it was built there could be found within its thick walls the living history of the evolution of the steam engine epitomized and in action. Unlike all other histories of the steam engine, the opening chapter did not begin with the exploits of Hero, of Alexandria, 120 years before Christ, but started in several pages ahead of October, 1901, on which date the plant sent out its first electrical impulse.

When the New York Edison Company decided to build Waterside Station it took the bridles off the engineers and allowed them to go as far as they liked in designing a plant that would be the last word in steam engineering, for the plant was intended to be big enough to meet all demands for years to come. Power was furnished by vertical, three cylinder compound engines of 5,000 horse power, which were considered something marvelous both in size and economy, eleven years ago. But before steam had been turned on for the first time the Curtis turbine had thrown down the gauntlet to reciprocating engines of whatever size or kind, offering to give them cards and spades and beat them out in the matter of economy. So a turbine of 2,000 horse power was installed almost at the beginning to show what it could do. It did so well that a turbine of 10,000 horse power soon took its place beside the pioneer. All the various examples of different periods in the evolution of the steam engine worked together in harmony, sending their currents out over the same wires in one united stream to light the Great White Way and more useful, if less popular, places.

Before the plant could be started up the company realized that forty thousand horse power, instead of being enough to meet all demands for years, wasn't even enough to begin business with; so the architect was routed out of bed and told to get busy on an extension. Since then neither architect nor engineer have had time to go out to lunch, for the plant has been steadily increasing in capacity until now it aggregates approximately three hundred thousand horse power, and it is still growing night and day. At the present time the company is replacing its vertical compound engines of 5,000 horse power with Curtis steam turbines of 27,000 horse power, by far the largest steam engines the world has ever seen. A single one of these monsters would supply electric current enough to meet the requirements of a city of 250,000 inhabitants; yet one of them takes up no more space than that occupied by the vertical compound engines of one-fifth their power.

This may seem to be going some, yet the evolution of the steam engine is proceeding at such a terrific pace that even so persevering a corporation as the Edison Company might be pardoned for feeling discouraged. In a gloomy corner of this titanic power plant a new idea has sprouted which may oblige the Edison Company to send the first of its 27,000 horse power Curtis turbines to the scrap heap before the last one can be installed. And this brings us back to the tall man.

He is none other than Nikola Tesla, whom the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, by vote of its members, placed seventh in the list of the greatest twenty-five names in electrical science. Tesla has invented a steam turbine. Of course this in itself is nothing worth mentioning, for everybody who is anybody has invented a steam turbine. And as there are steam turbines aggregating 5,166,000 horse power hard at work in the United States today, nearly all installed within the last six years, there is nothing sensational in the mere existence of such a prime mover.

But Tesla's turbine is different. Everything that Tesla does is different. Instead of studying for the priesthood as his father wished, Tesla went out to the stable at his home in far-off Hungary one day when he was very much younger than he is now and tried to fly from the roof with no other aid than that afforded by an old umbrella. The next six weeks he spent in bed. Since then he has been careful to keep his corporeal substance on solid ground; but his fancy essays some marvelous flights. It was Tesla, for instance, who proposed to signal from Long Island to the people on Mars by means of Hertzian waves of exceptional force. It was Tesla, too, who conceived the idea of wireless transmission of power, not to mention other enterprises daringly original. All this goes to show that while Tesla has a long list of practical achievements to his credit he is, in many things, decades, if not centuries, ahead of his times.

When such a man turns his attention to the things of every day life he may confidently be counted upon to produce something original. As every one who is informed upon the subject knows, the fundamental feature of the steam turbine is a wheel bearing upon its periphery a series of vanes or buckets. A jet of steam blowing upon the buckets pushes the wheel around and thus generates power. Many variations have been embroidered upon this elementary feature to produce the long list of turbines upon the market; but in none of them is the bucket dispensed with. It took Tesla to do that, though E. C. Thrupp, of England, tried to do it eleven years ago, and others have also tinkered vainly at the idea.

Tesla's turbine is the apotheosis of simplicity. Its working parts consist of nothing in the world but some smooth disks of steel only one thirty-second of an inch in thickness mounted about seven sixty-fourths of an inch apart upon a shaft. This assemblage of disks upon a shaft, called a "rotor," being placed within a steam-tight steel casing in which is an opening on the periphery to admit steam and another at the center of one side to allow it to escape, completes the turbine. Lacking the essential element of a turbine, the bucket, it really isn't a turbine; but as the inventor has not yet had time to think up a suitable name for it the familiar designation must answer present purposes.

To go into more minute particulars, the opening for the admission of steam is placed so that the jet strikes the periphery of the disks tangentially. As for the disks themselves, a part of their center is cut away as near as possible to the shaft so that there are three passages from side to side parallel with the shaft at equal distances apart. At one side of the casing opposite these openings is the exhaust port.

At first glance it might appear that when steam was admitted it would simply blow through between the disks and out at the exhaust port without causing the rotor to turn over. And really it almost does this, but not quite. Striking the periphery of the disks at a tangent the steam does follow a short curve to the center at first, but still the curve is long enough to allow the steam to begin to push the disks around. As the disks begin to revolve the steam follows them part way, thus increasing the distance it has to travel to reach the outlet and at the same time giving it a greater hold upon the surface of the disks. This process continues until the rotor has attained full speed, when the steam is pursuing a spiral course from inlet to outlet which takes it several times around the disks in a course six or seven feet long before it finally escapes.

Tesla's turbine is so violently opposed to all precedent that it seems unbelievable, even when you see it at work. In the reciprocating engine the steam has the immovable cylinder head to brace itself against while it expands and pushes the movable piston ahead of it. In the reaction turbine it follows exactly the same principle, expanding between fixed buckets on the sides of a chamber and buckets on the rotor. Even in the impulse turbine there are buckets to give the steam a purchase. In the Tesla turbine there is not so much as a scratch for the steam to grip - nothing but smooth steel.

But the advantages of the earlier forms of the steam turbine and the seeming disadvantages of the Tesla motor are more apparent than real. Steam is a fluid; and when any fluid is used as the medium through which power is developed the most economical results are obtained when the changes in velocity and direction of the current are made as gradual and easy as possible. A diagram of the path followed by a jet of steam in a reaction turbine would look like the thread from an old chain stitch sewing machine ravelled out and thrown down loose. With such a zigzag course destructive eddies, vibration and shocks are inevitable. This is not saying that steam turbines are not highly efficient, for they are; but still they are a long way short of perfection. Another point that counts against the impossibility of attaining the ideal with the older forms of turbines is their delicate and difficult construction. The large ones contain many thousand blades or buckets, each one of which has to be machined and fitted separately. While turbines are much more economical than reciprocating engines in their own particular field they are, nevertheless, costly to build and maintain.

Tesla gets the cost of construction and maintenance down to an irreducible minimum by the extreme simplicity of his turbine. He can do this because he approaches the problem from an entirely new angle. Instead of developing power by pressure, reaction or impact on buckets or vanes he depends upon the properties of adhesion and viscosity which are common to all fluids, including steam.

The characteristic of viscosity is best exemplified by cold molasses. Any one who has had to go out to the smoke house in winter to draw a pitcher of molasses for the matutinal buckwheats does not need to look in the dictionary to ascertain what viscosity is. Nor is an unduly vivid imagination required to figure out what would happen if a stream of cold molasses were directed against the rotor of a Tesla turbine. There would be such an excess of viscosity that nothing whatever would happen except the machine would be all mussed up. But by heating the molasses its viscosity would be so much reduced that the fluid might trickle down slowly between the disks.

Water has much slighter powers of adhesion than hot molasses, but it does pretty well, even at that. Test the matter by twirling a big button by twisting strings passed through the eyes as children do to make a familiar plaything, holding the rim of the button in a basin of water. The way the water will fly will show very strikingly how so thin a liquid will adhere to a smooth disk.

Steam is less adhesive than water, but the difference is in degree only, not in kind. When steam is admitted to the Tesla turbine a thin film of it adheres to the faces of the disks with tenacity enough to exert a pull in the direction in which the jet is moving. At the same time the steam in the thin space between the disks is also held back by the molecular attraction between its particles and those adhering to the disks, which is another way of expressing viscosity, so that all the steam between the disks is helping to drag the rotor around. Of course the disks do not move as fast as the steam, for the velocity of steam is very great.

If the disks were placed too far apart the greater bulk of the steam would flow swiftly through, like the current in a river which flows more swiftly in the center than near its banks, without doing any useful work; but the space is carefully calculated so as to make each molecule of steam exert a long pull, a strong pull and a pull all together with its neighbors, and thus do all the work it is capable of doing under the circumstances.

After Tesla had worked out the theory of his turbine he had one built, then obtained of the Edison Company permission to conduct his experiments at Waterside Station where there is an abundance of superheated steam, vacuum and all other essentials, including surroundings which might be supposed to be inspiring in such an undertaking, for the very air in the great buildings seems to vibrate with irresistible power.

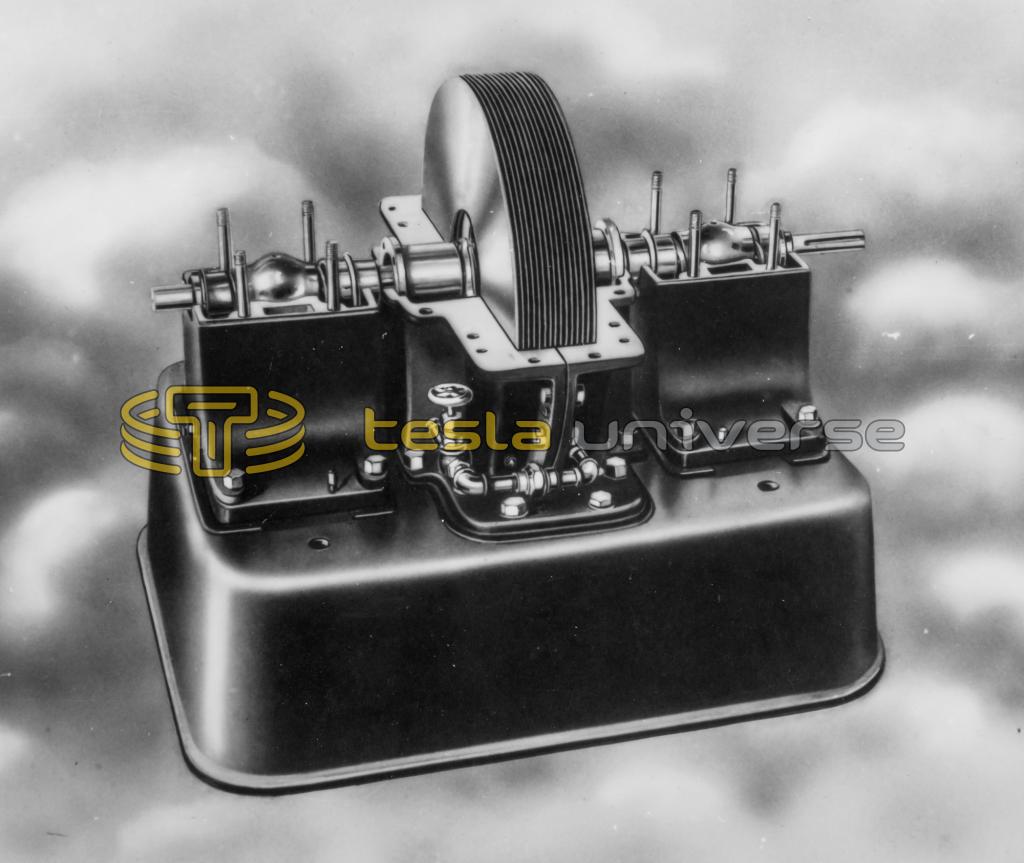

On a base which raises it a few inches above the steel floor is an object shaped like a cheese, actually no bigger than a derby hat of average size. Within the black casing is a rotor made up of steel disks 9¾ inches in diameter and measuring but two inches across the face. Yet this insignificant black cheese makes a fifty kilowatt generator hump itself. Actually it is capable of developing 110 horse power. It has to be geared down, for it is too swift for any generator that ever was built.

When Tesla escorted the first installment of guests around to inspect the new turbine he remarked casually that it ran at 16,000 revolutions per minute. To ask any engineer to believe such a tall statement was putting altogether too great a strain upon credulity. The guests smiled indulgently and winked at each other behind Tesla's back. But when the inventor applied a revolution counter that bit of brass mechanism went into spasms, then calmed down enough to indicate 16,000 revolutions a minute, whereat the eyes of the visitors protruded until they were unable to wink again for a fortnight.

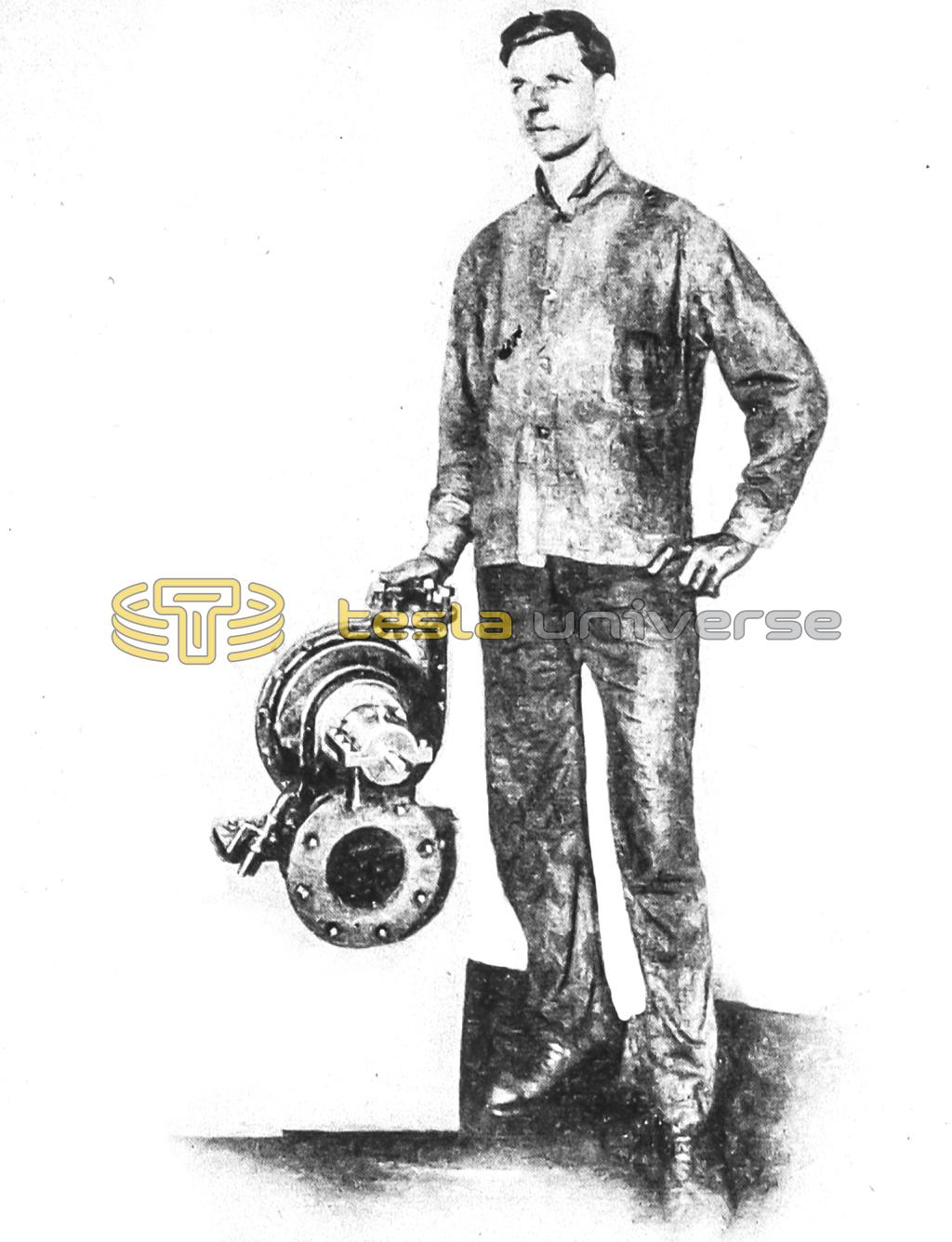

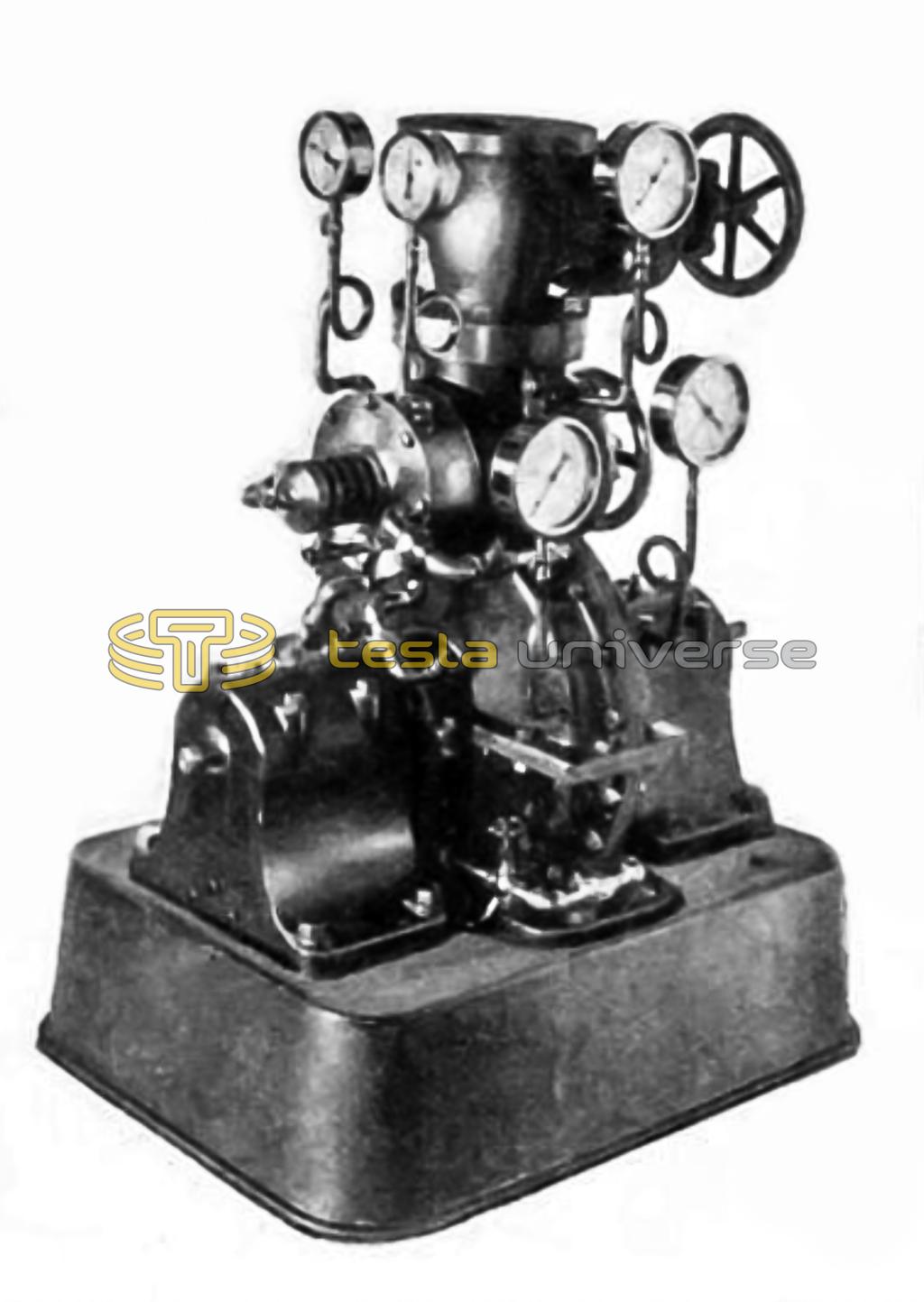

Beside this first Tesla turbine stand two larger ones, coupled together by a flexible shaft so that one may be used as a brake to test the power developed by the other. Taking steam at 125 pounds pressure and exhausting into the open air, making 9,000 revolutions per minute this larger turbine develops 200 horse power. At 185 pounds pressure as used by its big neighbors, it is capable of developing 300 horse power. Yet this new turbine stands on a base only 20 by 35 inches and measures but 5 feet from the floor to the top of the throttle valve. The weight is only 400 pounds, or two pounds per horse power. The rotor is composed of 25 disks 18 inches in diameter, spaced so that they measure 3½ inches across the face. So compact is this newest of steam engines that one developing 27,000 horse power would only occupy about one-tenth of the space required for the wonderful Curtis turbines on the farther side of the room. The pair of larger turbines are thickly studded with gauges of various sorts used by the inventor in his tests and experiments.

The method of testing the capacity of the turbine is interesting. The two turbines, exact counterparts of each other, are connected by a torsion spring which has been carefully calibrated so that its strength is accurately known. Steam is admitted to the turbine used as a brake in the direction opposite to that in which the disks revolve. On the shaft of the brake turbine is a hollow pulley in which are two slots diametrically opposite each other with an electric light inside close to the rim. As the pulley revolves two flashes of light are seen which with the aid of mirrors and lenses are carried around so that they fall upon two revolving mirrors placed back to back on the shaft of the driving turbine. The mirrors are set so that when there is no torsion on the spring the light is a stationary spot at zero on a scale. As soon as a load is thrown on the spring the beam of light moves up the scale which is so proportioned to the spring that the horse power can be accurately read from it.

In various tests this turbine has consumed 38 pounds of saturated steam per horse power per hour, which is a high efficiency, considering that the steam only gave up 130 British thermal units, and that power is developed in a single stage instead of in several as in other turbines or in triple expansion reciprocating engines. This is equivalent to a consumption of less than 12 pounds per horse power per hour of the superheated steam with the high vacuum used by the monster Curtis turbines near by. Tesla declares that with a large multiple stage turbine of his own type he will be able to develop 97 per cent. of the available energy in the steam, and this with a motor weighing but a quarter of a pound per horse power capacity. Certainly he is doing remarkable things.

A notable advantage possessed by the Tesla turbine is the ease with which it can be reversed. The great drawback to the marine turbines now in use is the difficulty of reversing. It is necessary to have two turbines on each shaft: one for going ahead and one for backing. In the Tesla turbine all that is necessary is to shut off steam on one side of the casing and admit it on the opposite side. There are no ponderous levers to throw, no reversing mechanism whatever, no moving parts but the valves in the steam pipes.

Yet more marvelous is the fact that the new motor is as well adapted to the use of gas as of steam. For years dozens of inventors have racked their brains, squandered their money and sacrificed their sleep in vain efforts to produce a practical gas turbine. But the obstacles in the way appeared insurmountable. Tesla has solved the problem. He has two gas turbines now approaching completion which are to be sent to Europe. The time may not be far distant when automobile manufacturers may be announcing new models with turbine motors. The gas turbine is identical with the steam turbine, the gasoline being exploded in a separate combustion chamber and its heat reduced by a spray of steam or water when the jet is introduced at great velocity into the turbine.

As if this was not versatile enough for one invention the Tesla steam and gas turbine is also a pump and an air compressor. All that is necessary to transform the turbine into a pump is to take the rotor out of its casing and put it into another of slightly different form, - a "volute" casing, the engineers call it, and reverse the direction of the fluid. That is, the water to be pumped enters through the center of the side casing, passes through the interstices between the disks from center to circumference and flows out through the periphery of the casing.

The same molecular adhesion between the disks and the fluid and the molecular attraction between the film adhering to the disks and the fluid between them that imparts power to the steam turbine gives force to the stream of water passing through the pump or the air passing through the compressor. As the water enters at the center and as the motion of each point on the disk is circular its particles receive an impetus always at a tangent to the circular paths; and so it moves in a spiral path from center to circumference. If the outlet is wide open there is little resistance to flow in a radial direction. Pressure in the casing of the pump depends upon the velocity of the particles leaving the periphery of the rotor. By throttling the outlet the pressure is increased in proportion to the speed of the rotor, velocity being converted into pressure.

The capacity of the new pump is amazing. A nickel plated model in Tesla's office that one could carry comfortably in his overcoat pocket pumps forty gallons a minute against a head of nine feet. With a pump having disks 18 inches in diameter the inventor declares he can deliver 3,500 gallons a minute against a head of 300 feet.

But perhaps the most interesting feature about this unique invention is the use to which its proceeds are to be put. Upon being told that steps were being taken to place the turbine on the market I suggested to Tesla that he would soon be able to retire.

"Oh, no!" he exclaimed. "I shall be ready to begin work. I am going to use the money I get from my turbine to develop wireless transmission of power."