Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's System of Electric Power Transmission Through Natural Media - Summary

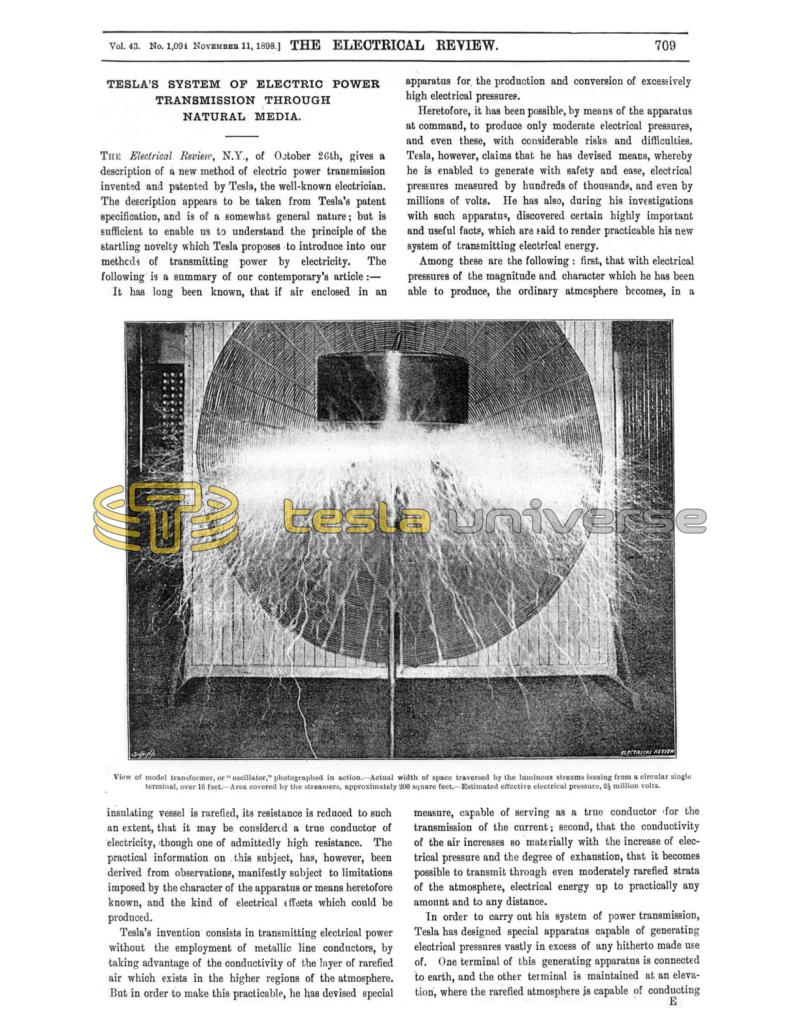

The Electrical Review, N.Y., of October 26th, gives a description of a new method of electric power transmission invented and patented by Tesla, the well-known electrician. The description appears to be taken from Tesla's patent specification, and is of a somewhat general nature; but is sufficient to enable us to understand the principle of the startling novelty which Tesla proposes to introduce into our methods of transmitting power by electricity. The following is a summary of our contemporary's article: -

It has long been known, that if air enclosed in an insulating vessel is rarefied, its resistance is reduced to such an extent, that it may be considered a true conductor of electricity, though one of admittedly high resistance. The practical information on this subject, has, however, been derived from observations, manifestly subject to limitations imposed by the character of the apparatus or means heretofore known, and the kind of electrical effects which could be produced.

Tesla's invention consists in transmitting electrical power without the employment of metallic line conductors, by taking advantage of the conductivity of the layer of rarefied air which exists in the higher regions of the atmosphere. But in order to make this practicable, he has devised special apparatus for the production and conversion of excessively high electrical pressures.

Heretofore, it has been possible, by means of the apparatus at command, to produce only moderate electrical pressures, and even these, with considerable risks and difficulties. Tesla, however, claims that he has devised means, whereby he is enabled to generate with safety and ease, electrical pressures measured by hundreds of thousands, and even by millions of volts. He has also, during his investigations with such apparatus, discovered certain highly important and useful facts, which are said to render practicable his new system of transmitting electrical energy.

Among these are the following: first, that with electrical pressures of the magnitude and character which he has been able to produce, the ordinary atmosphere becomes, in a measure, capable of serving as a true conductor for the transmission of the current; second, that the conductivity of the air increases so materially with the increase of electrical pressure and the degree of exhaustion, that it becomes possible to transmit through even moderately rarefied strata of the atmosphere, electrical energy up to practically any amount and to any distance.

In order to carry out his system of power transmission, Tesla has designed special apparatus capable of generating electrical pressures vastly in excess of any hitherto made use of. One terminal of this generating apparatus is connected to earth, and the other terminal is maintained at an elevation, where the rarefied atmosphere is capable of conducting freely the particular kind of current produced. Then at the distant point where the energy is to be utilised, a terminal is maintained at an equally high elevation, to receive the current and to convey it to earth through suitable means for transforming and utilising it.

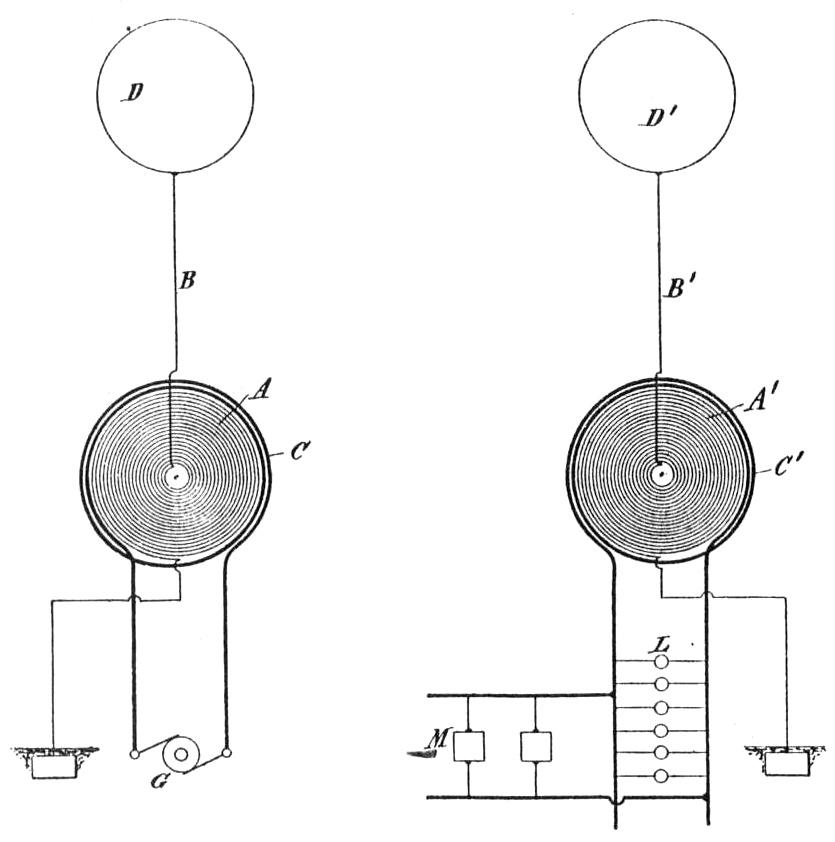

The apparatus by means of which this method of transmission may be effected, is represented diagrammatically in the accompanying figure.

A is a coil, generally of many turns, and of very large diameter, wound in spiral form, either about a magnetic core or not, as desired. C is a second coil formed by a conductor of much larger size and smaller length, wound around in proximity to the coil A.

In the transmitting apparatus the coil A constitutes the high tension secondary, and the coil C the primary, of much lower tension, of a transformer. In the circuit of the primary, C, is included a suitable source of current G.

One terminal of the secondary, A, is at the centre of the spiral coil, and from this terminal the current is led by a conductor, B, to a terminal D, preferably of large surface, formed of, or maintained by such means as a balloon at an elevation suitable for the purposes of transmission as before described. The other terminal of the secondary, A, is connected to earth and, preferably, to the primary also, in order that the latter may be of approximately the same potential as the adjacent portions of the secondary, thus insuring safety.

At the receiving station a transformer of similar construction is employed, but in this case the long coil, A', constitutes the primary, and the short coil, C', the secondary of the transformer. In the circuit of the latter are arranged lamps, L, motors, M, or other devices for utilising current. The elevated terminal, D', connects with the centre of the coil, A, and the other terminal of said coil is connected to earth, and preferably also to the coil C', for the reasons above stated.

The length of the high tension coil of each apparatus should be approximately one quarter of the wave length of the electrical disturbance in the circuit, this estimate being based on the velocity of propagation of the electrical disturbance through the coil itself, and the circuit with which it is designed to be used. To illustrate this in accordance with accepted views, if the rate at which the current traverses the circuit, including the two high tension coils, be 185,000 miles per second, then a frequency of 925 per second would maintain 925 stationary waves in a circuit 185,000 miles long, and each wave would be 200 miles in length. For such a frequency Tesla would use in each high tension coil a conductor 50 miles in length, or, in general, with due allowance for the capacity of the leading wires and terminals, such length of conductor as would secure the highest electrical pressures at the terminals under the working conditions.

It will be observed that in coils of the character described, the potential gradually increases with the number of turns, and the difference of potential between adjacent turns is comparatively small, and a very high potential, impracticable with ordinary coils, may be successfully maintained.

As the main object of the invention is to produce a current of extremely high potential, this object will be facilitated by using a primary current of very considerable frequency. But the frequency of the current is, in a large measure, arbitrary, for if the potential be sufficiently high and the terminals of the coils be maintained at a proper elevation where the atmosphere is comparatively rarefied, the intermediate stratum will serve as a conductor for the current produced, and the latter will be transmitted through the air with, it may be, even less resistance than through an ordinary copper wire.

As to the elevation of the terminals D, D', it is obvious that this is a matter which will be determined not only by the condition of the atmosphere, but also by the character of the surrounding country. Thus if there be high mountains in the vicinity, the terminals should be at a great height, and generally, they should always be at an altitude much greater than that of the highest objects near them in order to reduce the loss by leakage. Since, by the means described, practically any potential that is desired may be produced, the currents through the air strata may be very small, thus reducing the loss in the air.

Tesla points out that the phenomenon involved in the transmission of electrical energy is one of true conduction, and is not to be confounded with the phenomena of induction or of electrical radiation which have heretofore been observed and experimented with, and which, from their very nature and mode of propagation, would render practically impossible the transmission of any considerable amount of energy to such distances as would be of practical importance.