Nikola Tesla Articles

Tesla's Work and Marconi's - The Former is the "Father of Wireless Telegraphy"

Lecture in Which Tesla in 1803 Described the Idea Which Marconi Subsequently Demonstrated Practically — Tesla's Theories Followed by Marconi.

Prof Slaby, inventor of the process of wireless telegraphy which the German Emperor has lately ordered to be used by all German warships, which is known as the Slaby-Arco system, has, in an interview in Berlin, given to Nikola Tesla the credit for making possible all the systems of wireless telegraphy now known.

Prof. Slaby refers to Mr. Tesla as the "father of wireless telegraphy," according to the published reports of his interview, and says that Tesla first explained and worked out in his book "Inventions and Researches," published in 1894, the theory which thereafter Marconi was the first to demonstrate practically. While he gives Marconi the credit for the demonstration Prof. Slaby ascribes the origin of wireless telegraphy to the New York inventor.

Probably few people outside of those interested in technical studies have read this first announcement of the theory and of the outline of a process for carrying it out that gave to the world the system of communication now in daily use on the seas. Indeed few know that Tesla promulgated it years before the first wireless message was sent.

The book referred to by Prof. Slaby as published in 1894 was really a republication of the facts and speculations put forth by Mr. Tesla in a lecture delivered before the National Electric Light Association at St. Louis at its sixteenth convention which was in session from Feb. 28 to March 3, 1893.

The lecture was given at a special evening session of the convention, and was entitled "Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena." It was published in the same year in the proceedings of the convention by order of the Executive Committee of the association.

Mr. Tesla had spoken at length upon phenomena produced by electrostatic force, and after devoting some attention to electrical resonance he said:

"In connection with resonance effects and the problems of transmission of energy over a single conductor, which was previously considered, I would say a few words on a subject which constantly fills my thoughts, and which concerns the welfare of all.

"I mean the transmission of intelligible signals, or, perhaps, even power, to any distance without the use of wires.

"I am becoming daily more convinced of the practicability of the scheme; and though I know full well that the great majority of scientific men will not believe that such results can be practically and Immediately realized, yet I think that all consider the developments in recent years by a number of workers to have been such as to encourage thoughtful and experiment in this direction.

"My conviction has grown so strong that I no longer look upon this plan of energy or intelligence transmission as a mere theoretical possibility, but as a serious problem in electrical engineering, which must be carried out some day.

"The idea of transmitting intelligence without wires is the natural outcome of the most recent results of electrical investigations. Some enthusiasts have expressed their belief that telephony to any distance by induction through the air is possible. I cannot stretch my imagination so far, but I do firmly believe that it is practicable to disturb, by means of powerful machines, the electro-static condition of the earth, and thus transmit intelligible signals, and, perhaps, power.

"In fact, what is there against the carrying out of such a scheme? We now know that electrical vibration may be transmitted through a single conductor. Why, then, not try to avail ourselves of the earth for this purpose? We need not be frightened by the idea of distance.

"To the weary wanderer counting the mile posts, the earth may appear very large; but to that happiest of all men, the astronomer, who gazes at the heavens, and by their standard judges the magnitude of our globe, it appears very small.

"And so I think it must seem to the electrician; for when he considers the speed with which an electric disturbance is propagated through the earth all his ideas of distance must completely vanish.

"A point of great importance would be first to know what is the capacity of the earth, and what charge does it contain if electrified? Though we have no positive evidence of a charged body existing in space without other oppositely electrified bodies being near, there is a fair probability that the earth is such a body, for by whatever process it was separated from other bodies — and this is the accepted view of its origin — it must have retained a charge, as occurs in all processes of mechanical separation.

"If it be a charged body insulated in space, its capacity should be extremely small — less than one-thousandth of a farad. But the upper strata of the air are conducting, and so, perhaps, is the medium in free space beyond the atmosphere, and these may contain an opposite charge. Then the capacity might be incomparably greater. In any case, it is of the greatest Importance to get an idea of what quantity of electricity the earth contains.

"It is difficult to say whether we shall ever acquire this necessary knowledge, but there is hope that we may, and that is by means of electrical resonance. If ever we can ascertain at what period the earth's charge, when disturbed, oscillates with respect to an oppositely electrified system or known circuit, we shall know a fact possibly of the greatest importance to the welfare of the human race.

"I propose to seek for the period by means of an electric oscillator, or a source of alternating electric currents. One of the terminals of the source would be connected to earth, as, for instance, to the city water mains; the other, to an insulated body of large surface.

"It is possible that the outer conducting body of large surface.

"It is possible that the outer conducting air strata of free space contain an opposite charge, and that, together with the earth, they may form a condenser of very large capacity. In such case the period of vibration may be very low, and an alternating dynamo machine might serve for the purpose of the experiment.

"I would then transform the current. to a potential as high as it would be found possible, and connect the ends of the high tension secondary to the ground and to the insulated body. By varying the frequency of the currents, and carefully observing the potential of the insulated body, and watching for the disturbance at various neighboring points of the earth's surface, resonance might be detected.

"Should, as the majority of scientific men in all probability believe, the period be extremely small, then a dynamo machine would not do, and a proper electrical oscillator would have to be produced, and perhaps it might not be possible to obtain such rapid vibrations.

"But whether this be possible or not, and whether the earth contains a charge or not, and whatever may be its period of vibration, it certainly is possible — for of this we have daily evidence — to produce some electrical disturbance sufficiently powerful to be perceptible by suitable instruments at any point of the earth's surface."

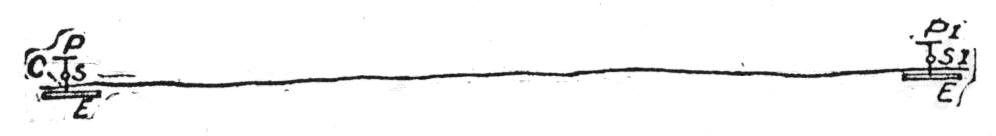

Mr. Tesla accompanied his lecture with a diagram illustrating his idea of the wireless telegraphy instrument, which is here reproduced. He said, referring to it:

"Assume that a source of alternating currents, S, be connected, as in the figure, with one of its terminals to earth (convenient to the water mains), and with the other to a body of large surface, P. When the electric oscillation is set up, there will be a movement of electricity in and out of P, and alternating currents will pass through the earth, converging to or diverging from the point C, where the ground connection is made.

"In this manner neighboring points on the earth's surface within a certain radius will be disturbed. But the disturbance will diminish with the distance, and the distance at which the effect will still be perceptible will depend on the quantity of electricity set in motion."

Just here it is interesting to note that Mr. Marconi in an interview with a reporter for The Sun a few weeks ago said regarding his experiments between Poldhu and Newfoundland that the electric waves produced by his plant at Poldhu "diminished with the increase of distance," but that they "came," that being the important thing. He said also that with greater power he would have better results.

Continuing his lecture Mr. Tesla said, with further reference to the diagram:

"Since the body P is insulated, in order to displace a considerable quantity, the potential of the source must be excessive, since there would be limitations as to the surface of P. The conditions might be adjusted so that the generator or source, S, will set up the same electrical movement as though its circuit were closed.

"Thus it is certainly practicable to impress an electric vibration, at least of a certain low period, upon the earth by means of proper machinery. At what distance such a vibration might be made perceptible can only be conjectured.

"I have on another occasion considered the question how the earth might behave to electric disturbances. There is no doubt that, since in such an experiment the electrical density at the surface could be but extremely small considering the size of the earth, the air would not act as a very disturbing factor, and there would be not much energy lost through the action of the air, which would be the case if the density were great.

"Theoretically, then, it could not require a great amount of energy to produce a disturbance perceptible at a great distance, or even all over the surface of the globe.

"Now, it is quite certain that at any point within a certain radius of the source S a properly adjusted self-induction and capacity device can be set in action by resonance. But not only can this be done, but another source, S2, similar to S, or any number of such sources, can be set to work in synchronism with the latter, and the vibration thus intensified and spread over a large area, or a flow of electricity produced to or from the source S1, if the same be of opposite phase to the source S.

"I think that, beyond doubt, it is possible to operate electrical devices in a city, through the ground or pipe system, by resonance from an electrical oscillator located at a central point.

"But the practical solution of this problem would be of incomparably smaller benefit to man than the realization of the scheme of transmitting intelligence, or, perhaps, power, to any distance through the earth or environing medium. If this is at all possible distance does not mean anything.

"Proper apparatus must first be produced, by means of which the problem can be attacked, and I have devoted much thought to this subject. I am firmly convinced that it can be done, and hope that we shall live to see it done."

In March and May, 1900, Mr. Tesla secured patents additional to those which he took out in the years immediately following the first announcement of his theory, these later ones covering developments of his system for the transmission of electrical energy, carrying it far beyond what he had at first suggested, but along the same general lines.

In the specification which forms part of the letters patent dated March 20, 1900, Tesla says, in the formal notice to the public as to what it is that the patent covers:

"I have been led to the discovery of certain highly important and useful facts which have hitherto been unknown. *** In illustration of these facts a few observations which I have made with apparatus devised for the purposes here contemplated, may be cited.

"For example, a conductor or terminal, to which impulses such as those here considered are supplied, but which is otherwise. insulated in space and is remote from any conducting bodies, is surrounded by a luminous flame-like brush or discharge, often covering many hundreds or even as much as several thousands of square feet of surface, this striking phenomenon clearly attesting the high degree of conductivity which the atmosphere attains under the influence of the immense electrical stresses to which it is subjected.

"This influence is, however, not confined to that portion of the atmosphere which is discernible by the eye as luminous and which, as has been the case in some instances actually observed, may fill the space within the spherical or cylindrical envelope of a diameter of sixty feet or more, but reaches out to far remote regions, the insulating qualities of the air being, as I have ascertained, still sensibly impaired at a distance many hundred times that through which the luminous discharge projects from the terminal and in all probability much further.

"The distance extends with the increase of the electro-motive force of the impulses, with the diminution of the density of the atmosphere, with the elevation of the active terminal above the ground, and also, apparently, in a slight measure, with the degree of moisture contained in the air. ***

"It is, furthermore, a fact that such discharges of extreme tensions, approximating those of lightning, manifest a marked tendency to pass upward away from the ground, which may be due to electro-static repulsion, or possibly, to slight heating and consequent rising of the electrified or ionized air.

"These latter observations make it appear probable that a discharge of this character allowed to escape into the atmosphere from a terminal maintained at a great height will gradually leak through and establish a good conducting path to more elevated and better conducting air strata, a process which possibly takes place in silent lightning discharges frequently witnessed on hot and sultry days.

"It will be apparent to what an extent the conductivity imparted to the air is enhanced by the increase of the electro-motive force of the impulses when it is stated that in some instances the area covered by the same discharge mentioned was enlarged more than sixfold by an augmentation of the electrical pressure. amounting scarcely to more than 50 per cent."

It may be noted here that Mr. Marconi, when he went back to Cornwall after his first Newfoundland experiments, saying that he would increase the power of his plant at Poldhu, made the statement that he had found that an increase of power showed itself multiplied many fold in the greater proportional distance to which his electric waves would carry.

Mr. Tesla's specification in his patent, continues:

"By the discovery of these facts and the perfection of means for producing in a safe, economical and thoroughly practicable manner current impulses of the character described it becomes possible to transmit through easily accessible and only moderately rarefied strata of the atmosphere electrical energy not merely in insignificant quantities, such as are suitable for the operation of delicate instruments and like purposes, but also in quantities suitable for industrial uses on a large scale, up to practically any amount and, according to all the experimental evidence I have obtained, to any terrestrial distance.

"Expressed briefly, my present invention, based upon these discoveries, consists, then, in producing at one point an electrical pressure of such character and magnitude as to cause thereby a current to traverse elevated strata of the air between the point of generation and a distant point at which the energy is to be received and utilized."

After describing his apparatus Mr. Tesla goes on to say:

"While the description here given contemplates chiefly a method and system of energy transmission to a distance through the natural media for industrial purposes, the principles which I have herein disclosed and the apparatus which I have shown will obviously have many other valuable uses — as, for instance, when it is desired to transmit intelligible messages to great distances, or to illuminate upper strata of the air, or to produce, designedly, any useful changes in the condition of the atmosphere, or to manufacture from the gases of the same products, as nitric acid, fertilizing compounds, or the like, by the action of such current impulses, for all of which and for many other valuable purposes they are eminently suitable, and I do not wish to limit myself in this respect."

In his specification in connection with the patent granted May 15, 1900, Tesla says:

"This application is a division of an application filed by me on Sept. 2, 1897, serial number 850,343, entitled 'Systems of Transmission of Electrical Energy,' and is based upon new and useful features and combinations of apparatus shown and described in said application for carrying out the method therein disclosed and claimed.

"The invention which forms the subject of my present application comprises a transmitting coil or conductor, in which electrical currents or oscillations are produced, and which is arranged to cause such currents or oscillations to be propagated by conduction through the natural medium from one point to another remote therefrom and a receiving coil or conductor at such distant point adapted to be excited by the oscillations or currents propagated from the transmitter."