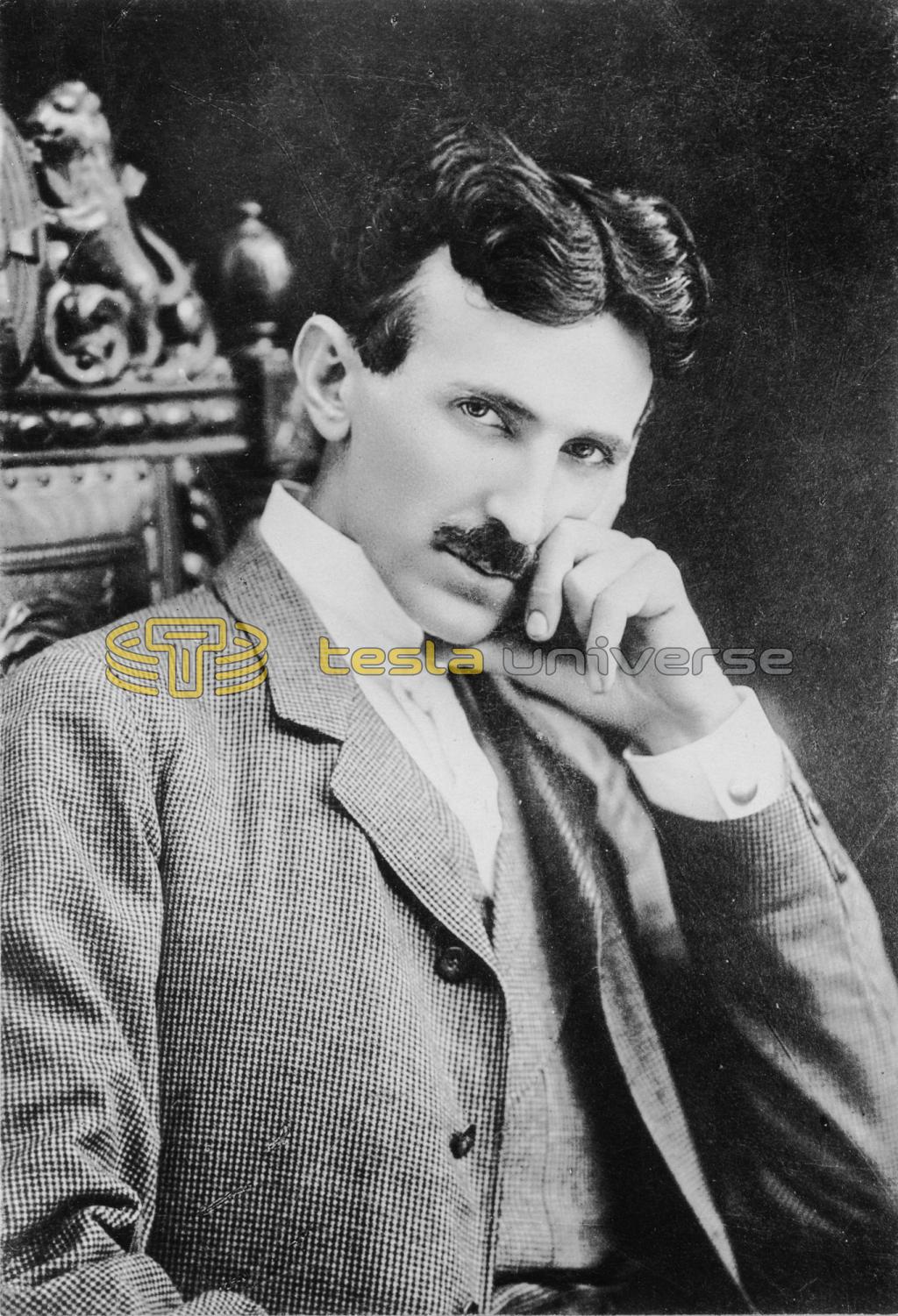

Nikola Tesla Articles

Wireless Power

A bolt of lightning passing through the earth, and returning to the point of entry with undiminished force, was the astounding discovery made by Nikola Tesla, "Wizard of Electricity," inventor, scientist, scholar.

At the issue of this momentous discovery Professor Tesla has perfected a practical system of wireless power distribution. And the universal application of the wireless transmission of energy will speedily solve vast and far reaching problems in commerce and the industries, and will eventually revolutionize the whole structure of the world's social and political economy.

Already Tesla has advanced his discovery of wireless transmission of electrical energy to the point of practical application. At his great experimental plant on Long Island he has secured actual and satisfactory results in wireless power transmission that go far toward making for its early and successful introduction into commercial and industrial uses. When all the details of his transmitting system are complete, and the world at large shall adopt wireless power in its general utilities, the wonders of science and invention, of dynamics and mechanics, the arts and the social scheme, that we employ and enjoy today will appear as the antiques of a primitive age.

The magic Lamp of Aladdin was never rubbed to such fruitful purpose, nor did it ever create such undreamed-of wonders, as will the application of the wireless transmission of energy to some of the most simple contrivances, the everyday utilities of the present; let alone the improved devices that will develop in its use, which with inventive genius will provide us for the future.

In recounting the incidents leading up to and the elemental details of the discovery that unexpectedly and unquestionably opened the way to this great realization, Tesla recites that during a systematic research, for which he had long trained himself, which he had assiduously conducted for several years, to the end of perfecting a system of wireless transmission of energy through the natural media, the earth and air, he came in 1898 to recognize three essential requirements. The first was to produce a transmitter of tremendous power; the second, to perfect a system for individualizing and isolating the energy transmitted; the third, to acquaint himself with the laws governing the propagation of electrical currents through the earth and air.

In May, 1899, Professor Tesla selected, for various scientific reasons, a large plateau sixty-five hundred feet above sea level, in the vicinity of Colorado Springs, where the surroundings contributed ideal conditions for careful observations. Such were the climatic and other conditions that he could hear claps of thunder four to five hundred miles away; and he could have improved upon this record had it not been for the tedium of waiting for the sounds to arrive, in definite intervals, as shown by an electrical indicating device - nearly an hour before.

Having established his laboratory and adjusted the highly sensitive instruments necessary to the proposed experiments, he learned that the earth was literally alive with electrical vibrations. Colorado, with its dry and rarefied atmosphere, is famed for its natural displays of electricity; static electricity being abundantly developed. The discharges of lighting during storms are not only frequent, but often violent to an inconceivable degree. During his stay there were in the course of one electrical storm approximately twelve thousand discharges within an observed period of two hours, occurring inside a radius of less than thirty miles. Many of these discharges were so heavy that they resembled gigantic trees of fire.

About a month after his Colorado observations began Tesla was both surprised and puzzled to note that his instruments were affected more decidedly by discharges taking place at great distances than those nearby. This presented a perplexing problem, which was made the more mystifying when careful observation disclosed the fact that the differences were not due to intensity of discharges, nor varying relation between the periods of the receiving circuits and those of terrestrial disturbances.

One night, when meditating over these experiences, "says Tesla, "I was suddenly staggered by a thought. The same thought had presented itself to me years ago; but I had then dismissed it as absurd and impossible. And that night when it recurred to me I banished it again. Nevertheless, my instinct was aroused, and somehow I felt that I was nearing a great revelation.

"It was on the third of July (1899) when I obtained the first decisive experimental evidence of a truth of overwhelming importance for the advancement of humanity. A dense mass of strongly charged clouds gathered in the west, and toward evening a violent storm broke loose which, after spending much of its fury in the mountains, was driven away with great velocity over the plains. Heavy and long persisting arcs formed almost in regular time intervals. My observations were now greatly facilitated and rendered more accurate by the experiences already gained. I was able to handle my instruments quickly, and was prepared. The recording apparatus being properly adjusted, its indications became fainter and fainter with the increasing distance of the storm, until they ceased altogether. I was watching in eager expectation. Sure enough, in a little while the indications again began, grew stronger, gradually decreased, and ceased once more. Many times, in regularly recurring intervals, the same actions were repeated, until the storm, as evident from simple computations, with nearly constant speed had retreated to a distance of about two hundred miles. Nor did these strange actions stop then, but continued to manifest themselves with undiminished force.

"When I made this discovery I was utterly astounded. I could not believe what I had seen was really true. It was a great revelation of Nature to accept immediately and unhesitatingly. Subsequently I confided my discovery to my assistant, and he afterward confirmed it, as did also a noted engineer in a German university. Several opportunities were presented later which brought out still more forcibly and unmistakably the true nature of the wonderful phenomenon. No doubt whatever remained - I was observing stationary waves! Impossible as it seemed, this planet, despite its vast extent, behaved as a conductor of limited capacity.

"All effects diminish as the extreme line of their radius increases. For instance, sound effects would be exhausted within a given radius, which would be determined by atmospheric conditions. The general law is that at one-half the distance the intensity of the effect is four-fold. And this is also true of electrical activities. But this discovery demonstrated something that was altogether contradictory to all previous experience. Not only could an electrical current be passed through the earth with undiminished intensity, but, under certain conditions, its force would be even augmented with distance.

"Had this discovery been worked out at that time it would have given us practical wireless transmission of power on a commercial scale at least ten years ago. The world, however, was not then, and is not yet, ready to receive it. Man - that is, the layman, the man unversed in dynamic forces and scientific engineering - does not understand how one element is related to another. If I had attempted at that time to place upon the market an apparatus for the wireless transmission of power, the world would not have utilized it. It may be years before it is educated to receive these new ideas and the perfection of this discovery. It is difficult for the average citizen to comprehend or to form an adequate idea of the tremendous significance of this marvelous revelation of Nature, or the stupendous possibilities that the development and perfection of this discovery assure as a heritage to humanity."

The full development of a possible twenty-five hundred millions of horsepower from the waterfalls and streams of the United States has been materially handicapped and restricted by the limited area over which hydroelectric energy may be practically transmitted by wire. The falls of Niagara alone could be made to supply a fifth of all the power used at present by industry and the railroads. At some remote day their power may be entirely utilized by diverting the full volume through tunnels to turbines at night, charging immense storage batteries with its energy for use during the next twelve hours, and again turning the water over the falls during the day to satisfy the sentiment of the people.

Aside from Niagara, however, most of the great power sites of the country are so distant from the centers of population that it has been impracticable to transmit their energy to localities containing the heart of our industries, and in many instances, particularly among the Western mountains, they are so inaccessible as to make it difficult or inconvenient to establish industries about these sites or within reach of electrical power transmission. But with wireless transmission of power the energy of the waterfall of the Columbia River - which by the way, amounts to seven or eight million horsepower - can be employed to run the motors of industry, to light and heat homes and cook food on the Atlantic seaboard as readily as on the Pacific, in Portland, Maine, as well as in Portland, Oregon; or the five million horsepower from the Sacramento River, in Manila as easily as in San Francisco. There is millions more than enough horsepower going to waste in the streams of the North Pacific group to turn every wheel of industry and move the traffic of every railroad in the country; and with the advent of wireless power it will be developed, along with other millions of hydroelectric power otherwhere, as consumption creates a demand for it.

The greatest power site in the world, Zambesi Falls, was recently discovered in the until then unexplored heart of Africa. Over its brink has gone to waste thirty-five million horsepower every minute of each day for centuries, enough energy to provide a large part of the world with power, more than enough to supply the commerce and industry of the United States. Because of its isolated location it is useless to mankind, and will be until wireless power makes it possible to set the wheels of a thousand industries spinning anywhere on earth with its magnificent energy.

While the general public has not been taken into Tesla's confidence concerning the progress of his work in the perfection of his system for the wireless transmission of power, scientific and electrical engineers in all countries have followed closely and with intense interest such developments as he has revealed to the technical world. For obvious reasons, however, it would not be prudent to disclose the actual working details of the system, or the specific nature of the apparatus to be employed, until such time as he may elect to place his transmitter on the market for commercial purposes.

"There is," says Tesla, "much misunderstanding in regard to my wireless system. Some believe that the transmission is effected through the air, and others that the currents go only through the earth. The fact is both media serve as vehicles of energy. The current passes through the earth; but an equivalent electrical displacement also occurs in the air, exactly as when the transmission is effected through a single wire without return; a principle the practicability of which I demonstrated in my earlier investigations.

"By this system," he continues, "wireless power can be transmitted with absolutely the same facility to the antipodes as it can to a distance of a few blocks. The quantity of energy the transmitter delivers is immaterial; but, in view of the fact that the earth is immense, and that there are practical limits in the amount of energy collected in any individual receiver, it is necessary to have a very powerful transmitting plant.

"However," he explains, "the volume of energy - the indicated horsepower of the generating plant - will not in the least affect the limit of transmission. That is, a plant generating two hundred horsepower will transmit its energy to the same unlimited terrestrial distance as that of a plant generating two hundred thousand horsepower. Neither will the energy or power decrease in efficiency as the distance of transmission increases, as in the case with electrical energy transmitted by wire. The efficiency of transmission will be the same, irrespective of the distance or the amount.

"When conveying power through a wire," Professor Tesla points out, "a certain loss is incurred, due to the resistance of the conductor; but the earth is a conducting body of such enormous dimensions that there is virtually no loss, so that distance means nothing. To the average intelligence this will appear incomprehensible. We are continuously confronted with limitations, and those truths which are contradicted by our senses are the hardest to grasp. For example, one of the most difficult tasks was to satisfy the human mind that the earth rotated round the sun; for to the eye it seemed just the opposite."

In regard to the cost of wireless power, an estimate is made that places it at about one-sixteenth that of the present means and sources of supply. At any rate, Tesla says that it will be far cheaper than any other source known to man. "With wireless energy," he continues, "we could avail ourselves of the waste power of the present: the transmission would involve but little expense, and the apparatus would be of the simplest and the cheapest."

The cost of wire transmission varies with the ratio of distance between point of generation and consumer, as determined by investment in and maintenance of conveying mains, which increases with distance. Also, over long lines, as from Niagara Falls to points some two hundred miles distant, the loss of current increases with each mile, and would, if the line were carried far enough, so decrease in volume that eventually the current would lose practical power producing energy. With the most improved means of wire transportation the limit of distance is placed by the most optimistic engineers at not much beyond five hundred miles. With wireless transmission there will be no limit, except that of terrestrial space, nor will the cost be greater in transmitting power to the antipodes than to the factory a block distant from the generating plant.

Tesla is assured that it will be absolutely unnecessary to have relay or transforming stations, since the consumer can receive the power direct, no matter where he may be situated. Also, there will be no conflict or interference of currents. Two factories situated in the same block, for instance, or two parallel railroads, or two competing steamship lines, could receive their power independently from separate sources, one from Africa, the other from Niagara. Also his perfected system of positive selectivity will absolutely prevent an unscrupulous consumer from stealing his power from the air, any more than he could use the key to his barn door for manipulating the time lock on a bank safe, so complete will be the individualization of currents. Also, this eliminates the element of power monopoly.

In the field of transportation wireless power will work some of the greatest changes in things as they are. First among all, the steam-driven train and ship will pass into history along with the cradle, the flail, and the spinning wheel. And the noisy chugging of the smoking, foul smelling automobile will soon be a memory.

Professor Tesla has so far perfected his original system of isolation in the transmission of wireless energy that he is able to control, for instance, an automation in the form of a miniature submarine ship, which he can readily direct and maneuver at will, - starting, stopping, speeding, turning, reversing, diving, rising, by the simple manipulation of wave impulse.

"When my system is complete," says he, "a crewless ship may be sent from any port in the world to any other port on the Seven Seas, propelled by wireless energy from a power plant anywhere on the face of the earth, and controlled and maneuvered absolutely and positively by telautomatics."

The ship in its actual position on the sea would not alone be visual to the telautomatic operator, but there also would be reproduced through the visualizing apparatus or aërocamera a detailed and faithful scene picturing her surroundings and the conditions of sea and weather.

Given wireless power and telautomatic control of ships at sea, the ever menacing bete noire of the mariner, the danger of collision in fog and night, or of going on the rocks or shoals, will be eliminated. For the crewless ship the operator, seated in his despatching office on land, surrounded by sensitive devices, with which any point he may elect of earth or sea may be visualized before him, would also "feel" the approach of another ship or the proximity to an iceberg or shoals, when he would easily deflect the course of the ship from danger. Ships carrying only cargo will be crewless, and they will be as water-and air-tight as a submarine, made buoyant by vacuum, and practically nonsinkable.

The future of wireless power development may render it folly for any nation to have afloat a vessel of war. The secret of another nation's scheme of selectivity might be disclosed to the enemy, when the guns of their own vessels might be turned against sister ships and a whole fleet destroyed by shells from their own guns, or their magazines might be exploded by the enemy at will. However, should there be battleships in the wireless future, they will be crewless. They will be maneuvered, their guns will be loaded, aimed, and fired, and their torpedoes discharged with unerring accuracy, by the director of naval warfare seated before a telautomatic switchboard on land.

"The time will come, as a result of my discovery," said Tesla, "when one nation may destroy another in time of war through this wireless force: great tongues of electric flame made to burst from the earth of the enemy's country might destroy not only the people and the cities, but the land itself. I realize that this is indeed a dangerous thing to advocate. At first thought it might mean the annihilation of the nations of the world by evilly disposed individuals. The public might at first look upon the perfection of such an invention as a calamity. We say that all inventions assist the criminal in his work. Today the safe burglar despises the use of dynamite, turning to electrical contrivances to cut the lock from a safe. It is fortunate for the world, therefore, that ninety per cent. of its people are good, and that only ten per cent. are evilly disposed: otherwise, all invention might be turned more greatly to evil than to good."

As with the ships of the sea, so also the gigantic freight ships of the aërial highways will be controlled, lifted in air, sent whizzing along at two hundred miles - the through express and mail possibly at three hundred or four hundred miles-an hour, lowered to scheduled landing places en route, the progress of the discharge and loading being visible to the operator, and again raised and put to flight by the telautomatic control despatcher at the headquarters of the line. The possibilities of the part crewless warships of the air may play by dropping earth-rending bombs upon the cities of the enemy, is obvious.

With wireless propelled passenger air carriers having decks closed or protected against the strangling, lung drowning rush through the air, traveling three or four hundred miles an hour through routes in high altitudes, one may have a six o'clock dinner in New York and breakfast next morning in San Francisco or London or Paris, or have luncheon in San Francisco and tea next day in Canton or Tokio.

The airship of Tesla's invention will neither be aëroplane nor dirigible, nor will it have wings or gasbags or propeller blades. All these things, he says, are impossible in the construction of a commercially practicable airship. The aeroplane he classes as no more than an amusing toy, a vehicle for exhibition by the venturesome sportsman; nor will it be anything more, because in its essential principles it has irremediable flaws that are absolutely fatal to commercial success. Tesla's airship will be proportionately as substantial, as stanch and dependable, and altogether as airworthy as the steamship of today is seaworthy. It will maintain a steady, even keel, and will not be in the least affected by air currents or any sort of weather conditions.

The size of these ships of the air may be limited only by the area of accommodations provided for their landing. Or they may be made small enough, being so easily and simply handled, that the school girl and boy may ride them to and from school, and in greater safety than walking in the city streets. The single or double or triple passenger aërocar of Professor Tesla's type will be more popular, too, for individual and independent transit, either for business or pleasure, than was the bicycle in its heyday, or the gasolene automobile at its best. Then the city commuter of the future may go and come between business and residence on his wireless aërocar, and he may go many miles farther afield, into the uncrowded hills and valleys and sea and lake shore, to make his home.

However, before the general public is fully educated to the popular use of aërial navigation as a common utility, wireless power will have been generally, if not universally, applied to the railroads. It is very probable, in fact, aside from the industries and ocean commerce, that wireless power will find its first application to rail traffic. It will be an ideal source of power, and the resulting advantages and economics will be, more truly than tritely, too numerous to mention in anything less than a volume.

Millions of tons of coal will be saved that are now consumed in hauling fuel to coaling points. The use of hydroelectric power will conserve the coal resources. The ponderous, track wearing steam locomotive will be abandoned to the scrapheap. The smoke and soot and grime of travel will be eliminated. Direct wireless connection with the motors under each car will discard the deadly third rail and the hundred-ton electric engine. Wireless controlled safety devices will make collision impossible, and the wireless trains will provide every comfort and electrical convenience of the latest thing in hotels.

The maximum of speed will be determined by the capacity of the track to withstand strain. And wireless power will make it cheaper to cut through mountains, fill valleys and bridge canons, than to operate on curves and grades. With these abolished and with roadbeds laid on approximate levels, straightaway as the crow flies for hundreds of miles, and with Tesla's gyroscopic mechanism to provide stability and prevent lateral impact, two or three hundred miles an hour may be maintained with safety and comfort. Then one might have breakfast overlooking the Golden Gate and attend a Broadway theater in the evening, and be home again before noon the next day.

Wireless power will make it possible to despatch crewless, light, cigar shaped steel mail cars on curveless, gradeless elevated or overhead tracks across country at an inconceivably terrific rate of speed. It may be telautomatically operated from a terminal switchboard, from where the train may be started, speeded, and stopped, or a "local" car dropped off and another taken on without pause at cities or junctions en route. Letters posted in New York in the morning may then be handed to the addressee by the postman in San Francisco on the afternoon delivery, or to the Chicago business man when he comes down to his office in the mid-forenoon.

One of the great handicaps to the existing system of wireless telegraphy is the serious interference with messages on account of imperfect control of selectivity, secured principally by tuning. Realizing that such interference limited its greatest usefulness, Tesla has long since been conducting experiments along altogether different lines of transmission, in which he has developed perfect isolation and selectivity. He has discovered that any desired degree of individualization of aërograph and aërophone massages may be attained by employing a large number of cöoperative elements and arbitrary variations of their distinctive features and order of succession, so that not only many thousands, but even millions, of simultaneous aërograph and aërophone messages may be sent through one conducting medium without the slightest interference.

The general term "World Telegraphy" has been suggested for Tesla's scheme of intelligence transmission, although "World Aerophony" would be as applicable, since his system will make it as practicable to talk as to telegraph through or round the globe, and as easily to a person using his aërophone at the antipodes as one in an office in the next block. Nor will it require a great, unwieldy contrivance for sending or receiving either aërograph or aerophone messages; such, for instance, as required in the present wireless system. Instead, Tesla assures us, for this purpose a small, cheap and extremely simple device, so compact and portable that it may carried in one's pocket, may be set up or held in one's hands anywhere on land or sea while it sends through intermediary transmitting plants messages to any part of the terrestrial universe, or receives such special messages as may be intended for it, or records the news of the world as constantly despatched from the various news distributing stations.

Professor Tesla is confident that his system of intelligence transmission constitutes, in its principles of operation, means employed, and capacities of application, a radical and fruitful departure from what has been done before. "I have no doubt," he adds, "that it will prove very efficient in enlightening the masses, particularly in still uncivilized countries and less accessible regions, and that it will add materially to general safety, comfort, and convenience, and maintenance of peaceful relations. It involves the employment of a number of plants, all of which are capable of transmitting individualized signals to the uttermost confines of the earth. Each of them will be preferably located near some important center of civilization, and the news it receives through any channels will be flashed to all points of the globe. Thus the entire earth will be converted into a huge brain, as it were, capable of response in anyone of its parts. Since a single plant of one hundred horsepower can operate hundreds of millions of instruments, the system will have a virtually infinite working capacity, and it must needs immensely facilitate and cheapen the transmission of intelligence."

With universal aërophony available by the use of a convenient pocket instrument, the balloonist dropping into the far interior of uninhabited Canada need never be featured in the news as "lost." The explorer striving to reach the earth's poles, or venturing into the wilds of the world's untraveled regions, will be able to keep in hourly touch with his friends, to report his progress to the world, or to send out a call for relief or rescue over bleak fields of ice, the desert wastes, or jungle fastnesses. Also, the man hunting in the big woods, or on a solitary journey on land or sea, can spend an otherwise lonely evening talking with the folk at home. There will never be any reports of "line's busy" by Central on this aëroline. Nor will there be any eavesdropping on "party lines" or delays through an inattentive Central; for, lo! there will be no Central. Each instrument and its operator will constitute an aerophone central in themselves; all calls being direct from the instrument calling to the one called. And any operator with his individual pocket instrument may call any other instrument anywhere on the face of the earth, simply by adjusting the selective device on his instrument to correspond with that of the one desired.

"At my plant on Long Island, "says this magician, "when all the apparatus is perfected for commercial use, I shall be able from my aerophone there to call up any 'phone in the universe, and, although apparently inconceivable, it is nevertheless true that my small voice through the delicate apparatus I am completing will be able to set the utmost confines of the whole world trembling with the vibrations of its force. As to the wireless telegraph of today and the incipient wireless telephone, they are but a puny step in the field of wireless transmission.

"Another valuable application of my wireless system," he continues, "will be the driving of clocks and watches from a master wireless time transmitter. These timepieces will be exceedingly simple, will require absolutely no attention, and will indicate rigorously correct time."

The farmer will be one of the greatest beneficiaries of the wireless transmission of electrical energy; and through him, as a result of increased yields and decreased cost of production, the people of the cities and the public at large.

Some years ago one of the great American inventors claimed the discovery that worn out soils could be made surprisingly productive by a more or less simple process of electrical treatment, and he rendered the world an immeasurable service in disclosing the process. But it ended there. To deliver a supply of electricity sufficient to consummate the process on the six million farms of the country was quite another problem; for in this case neither the valleys, the plains, nor the hillsides could go to Mohammed to be run as grist through his electric apparatus, but Mohammed must needs go with his equipment to wherever the land to be treated lay.

Through the perfection of his discovery Tesla will provide a way to deliver to every farm, not alone in the United States, but in the universe, enough electricity to apply the treatment effectively. And, presto! the farmer who today rides a plow behind a team of horses or draws a gang behind a tractor, may tomorrow in similar fashion ride an implement operated by wireless power, by which the soil, instead of being turned over as with the plow, will be lifted in furrow - deep slices and run through a wonderfully contrived machine in an endless ribbon, broken up into minute particles and made loose as ashes as it undergoes the necessary treatment by electricity, furnished as part of the wireless transmission, thoroughly pulverized and made firm as it leaves the implement into a perfect seed or plant bed, charged with sufficient available and soluble plant food to produce a quantity and quality of crop yield beyond the present expectations of the most sanguine of modern scientific agriculturists. It is claimed, too, as one of the advantages of wireless electricity, that it will be possible to control the weather in any locality to the extent of either preventing or producing rainfall to meet soil and crop requirements.

Of the two thousand million acres in continental United States, about half is estimated as being capable of cultivation in its present condition. Some of this is so dry you wouldn't think of raising even an umbrella on it. In 1910 our improved farm lands amounted to four hundred and seventy-five million acres. Irrigation and drainage are the principle factors that must solve the problem in the cultivation on most of the remaining vast areas that may be reclaimed and made tillable.

Wireless power offers the means of solution. Location presents no bar. Whether current is supplied from a power site in the community, or by a hydroelectric plant in the jungles of Africa, will be of no consequence; the cost will be the same. From distant streams or from great wells on the land the farmer may draw water in literal floods to irrigate his fields, through powerful rotary pumps, another of Tesla's inventions, which have many times greater capacity for their size and require less power than any pump heretofore produced. Or, on the other hand, he may drain semi - submerged and otherwise impossible marsh land, usually richest of all soil in natural fertility. With the coming application of wireless power to this end, our millions of acres of parched desert lands and dismal swamps may be converted into Gardens of Eden, whence will come billions of tons of grain and fruit and vegetables and millions of cattle from knee - deep pasture lands to meet the demands of an ever growing population.

More than that, every farmstead, wherever located, may have its own individual wireless terminals to operate its field implements, to drive its machinery, - its cutters, grinders, threshers, mills, - and also to lighten the labor in the home, by running the electric washer, wringer, dryer, ironer, the sewing machine, the dough mixer and baker, the chopper, spice mills, cream separator, churn, freezer, and do all the cooking, as well as heat the house in winter and run a refrigerating plant to cool it and manufacture ice in summer.

"In each instance," says Tesla, "a small terminal placed a little above the roof will be sufficient to furnish light, heat, and power for the isolated farm dwelling."

What farm dweller could feel isolated from the world with such conveniences, especially when there is included in the equipment of the country home a wireless "lineonews" continuously typing the important events of a universe, a wireless recordophone through which, as the operator may elect, may be heard the Sunday morning melody of the choir in St. Paul's or old Trinity, the grand operas of any city, the sermon in any church, the lecture in any lyceum, or may be seen clearly visualized in the simultaneous reproduction of the best dramas, while listening to the lines of the actors who may be playing hundreds or thousands of miles distant?

With such readily available sources of entertainment, to be had by turning a switch and pressing a key, the story of the erstwhile dreary winter's eve on the still lone but far from lonely farm, will soon be among the romances to be retold; for with the advent of perfected wireless transmission the farm life of the future may be made far more alluring than life in the cities.

And old Dobbin! Framed and hung somewhere in the farm home will be the picture of a horse, in reverent memory of a noble and worthy service done, that he may not be altogether forgotten in the new age of an energy that will not consume half the crops of a farm to run it, and with better success and profit than ever before.