Nikola Tesla Articles

The Wizardry of Tesla

Genius Left Out of History Books Gets His Due in Biography by BBC Professor

Progress has run into all sorts of image problems in our time.

Not only has the view become widespread that all progress is not good, we're also beginning to see that what we get from progress isn't always the best it has to give us.

The better mousetrap doesn't always win the day, in other words. The VHS videotape format beats out Betamax, MS-DOS PCs triumph over Apple Macintoshes, and more than a decade after the clarity of high-definition TV becomes possible, Americans still put up with TV pictures that look as if they've been filtered through a dust-furred Venetian blind.

These and other contemporary instances of the cynical hobbling of technology have shown us that, in progress as in all things human, pecuniary politics often rise above intrinsic merit -- and the greatest topicality of "Wizard," a book written by a Bristol Community College psychology professor and just published by Birch Lane Press, lies in its demonstrating to us that this has probably never been otherwise and that even greater outrages have been committed against the advancement of quality technology in the past.

From Marc J. Seifer's "Wizard" we learn that the cellular phone, that totem of the '90s, should have been around since the turn of the century. Fluorescent lights, which only came into use in the 1950s, were invented in 1898. As for the fax machine and remote control devices, by the time we began using them there should already have been a market for their antique versions.

But more startling than the setbacks those inventions suffered is the fact that they, along with radio, AC electricity and numerous others yet to be fully developed -- including wireless power transmission, the particle-beam weapons of President Reagan's Star Wars strategy, and even robotics -- are the brainchildren of just one man, someone who perhaps ought to be considered the true father of the age of technology but who you would be hard-pressed to find mentioned in American textbooks.

"Wizard" is a biography of this perplexingly obscure genius and it is the culmination of a 20-year endeavor that began in a rather obscure way for the author while he was dabbling on the UFO "fringe," doing research on Tibetan Buddhism for a publisher of New Age-type matter.

"I came across an article that claimed that a man from another planet had been raised by earth parents in Yugoslavia, where he had landed as a child in 1856," Mr. Seifer said. "He had been sent to Earth, the article claimed, to give us all these marvelous inventions."

The superman's name Nikola Tesla -- a name so obscure in our time, said Mr. Seifer, that British film director Nicholas Roeg saw no reason to allude to it in his film "The Man Who Fell To Earth," which was inspired by the UFO buffs' sci-fi version of the Tesla story -- a version Mr. Seifer himself thought ridiculous, although he was sufficiently intrigued by it to check a little further into its more earthbound claims.

"I found a book of patents and went into the history of all those inventions and I found that this Nikola Tesla really was the source for them," Mr. Seifer said. "I could not understand how such an important person could disappear from the history books."

Mr. Tesla so intrigued Mr. Seifer that he would make the inventor the topic of a doctoral dissertation in 1986, and then, over the next decade, expand that dissertation into "Wizard The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla, Biography of a Genius," which he says is the most comprehensive such work yet published on the inventor.

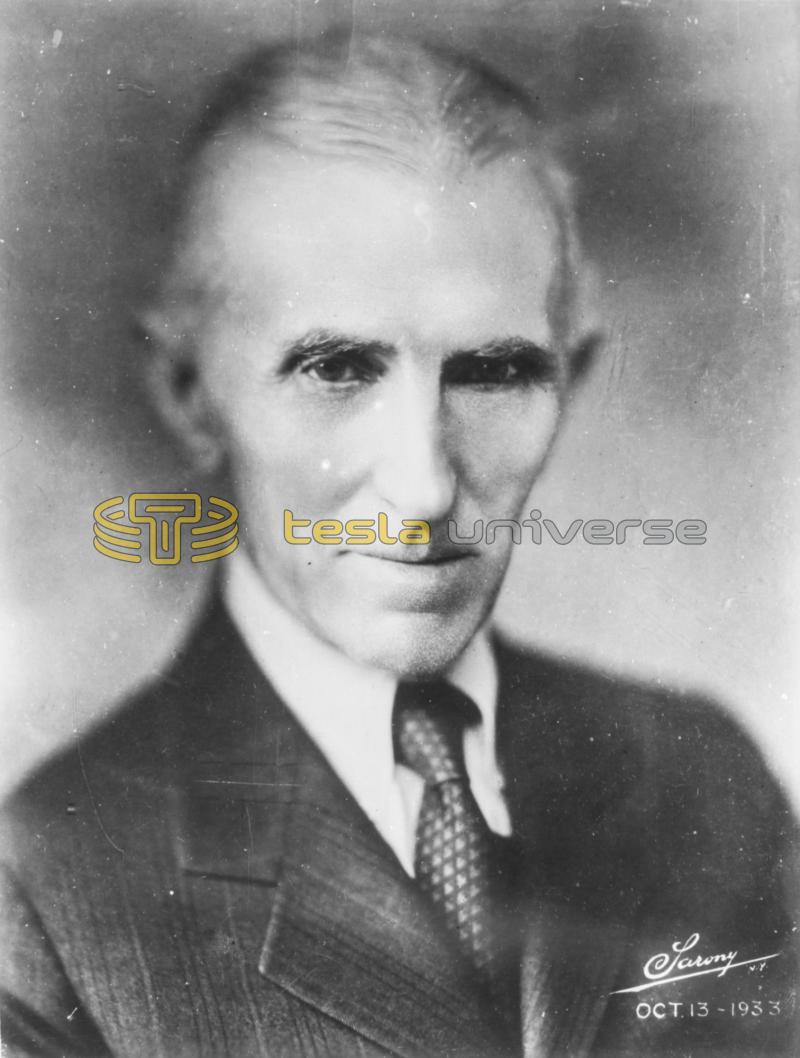

The introduction to "Wizard" is written by Mr. Tesla's grand-nephew, William H. Terbo, who praises the book for uncovering a lot of information about the inventor's life and relationships. Nikola Tesla (1856-1943), a Croatian-born Serb, emigrated to the United States in 1884 and established himself as an inventor only four years later with the patenting of his AC polyphase system, the technology at the heart of that early and enduring icon of American progress, the Niagara Falls hydroelectric project.

Mr. Tesla made $216,000 from the sale of the polyphase patent to Westinghouse, but he could have made much more if he had held on to it. According to Mr. Seifer's calculations, Mr. Tesla would, in fact, have made close to $12 million during his lifetime if he had kept all his patents.

But what money Mr. Tesla did make was enough to keep him in enviable style for much of his prime He lived at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, dined at the best restaurants, and, although celibately devoted to science, was part of the city's social elite, enjoying the admiration of coveted women and the company of Rudyard Kipling, Mark Twain and the architect Stanford White -- none of whom, however, outshone him in their celebrity. Nor did rival inventors such as Thomas Edison and Charles Steinmetz.

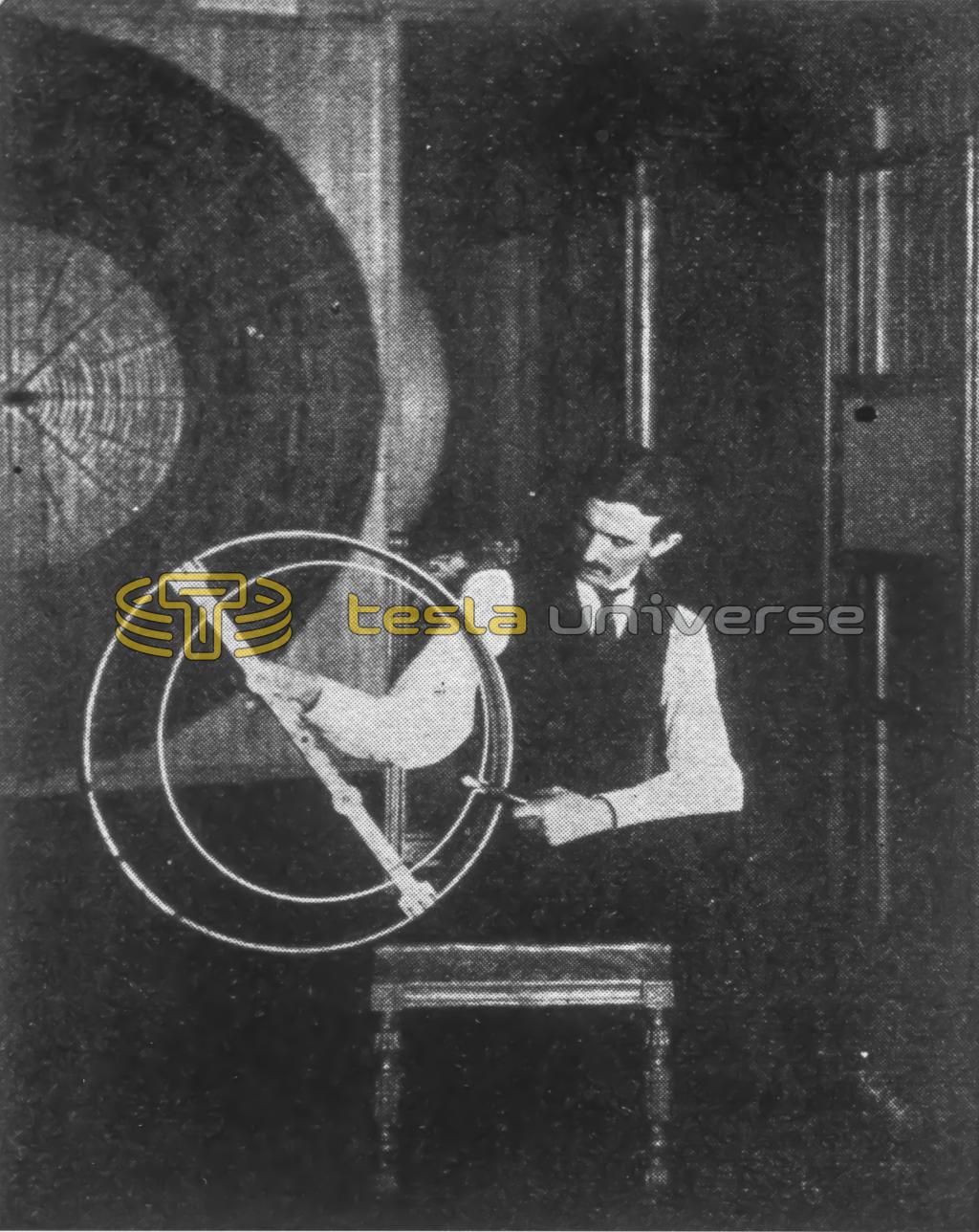

"In the 1890s, Tesla was one of the most famous people on the planet," said Mr. Seifer. "He was a showman, he was into PR. He would hold these exhibitions during which he would send bolts of electricity through his body. More than 3,000 people showed up to see him in St. Louis once."

His decline began when he and his principal backer, the arch-capitalist J.P. Morgan, parted ways over the construction of a wireless system. The break occurred even as the first of the system's fantastical-looking Magnifying Transmitter towers was going up on Long Island's Wardenclyffe -- 4 miles from where Mr. Tesla's latest biographer grew up and a spot to which he often swam as a child.

Mr. Morgan, who was heavily invested in wired systems, was not convinced he would benefit from wireless distribution, which would be more difficult to meter, Mr. Seifer said. And then Mr. Tesla became simply too fantastic for the pragmatic tycoon's taste.

In his eagerness to crush such rivals as Guglielmo Marconi (the man who would come undeservedly to be recognized as the inventor of wireless communication, but known to Mr. Tesla as only "a parasite and microbe of a nasty disease"), Mr. Tesla began envisioning a Morgan-financed global communication enterprise more efficient and spectacular than today's radio, television, wire service, lighting, telephone and power systems.

According to "Wizard," Mr. Tesla's ultimate goals included the production of rain in the deserts, the lighting of skies above shipping lanes, the wireless transmission of energy for automobiles and airships, a universal time-keeping apparatus, and interplanetary communication.

But from that perhaps megalomaniac pinnacle of ambition Mr. Tesla then progressed to a nervous breakdown, to an apparently cranky fixation with searching the radio spectrum for signs of extraterrestrial life, and to a mounting antagonism toward him in scientific and financial circles.

Near the end of his life, with his fame all but gone, Mr. Tesla was subsisting on a small stipend from Westinghouse and from his native Yugoslavia while living on arrears in a second-rate hotel. He died in 1943, and little happened after his death to arrest his slide into obscurity.

General Electric, according to Mr. Seifer, has been in great part responsible for turning the lights out on Nikola Tesla's name. "If he's not in the textbooks," Mr. Seifer said, "it's because a lot of the textbooks were written by GE and they needed to say that their man, Charles Steinmetz, invented the AC generator, so they wouldn't have to pay royalties to Westinghouse. As for Westinghouse, it also wanted to eliminate Mr. Tesla's name. It owned the patent and saw no need to promote the original inventor."

The two corporations, Mr. Seifer believes, also deliberately retarded the arrival of fluorescent lighting. "They were making money on selling light bulbs and extra power," he said.

But Mr. Tesla's place in history was jeopardized by a number of factors other than corporate connivance and callousness, according to Mr. Seifer. Among them:

- The inventor's loss to Mr. Marconi in the race to build the world's first wireless communications system -- even if Mr. Marconi's technology was in some of its more important components cribbed from Mr. Tesla's and, nonetheless, much inferior to Mr. Tesla's.

- The damage he inflicted on his own credibility when he publicized his belief that he was receiving communications from extraterrestrials. "He was picking up radio signals on his wireless equipment, probably from thunderstorms. But as far as he knew then, he was the only source of radio signals on earth, and if he were picking up signals from elsewhere, they had to be coming from extraterrestrials," Mr. Seifer said.

- Military secrecy. With the imminence of World War II, said Mr. Seifer, the American government apparently suppressed Mr. Tesla's invention of the particle-beam weapon to prevent its falling into the hands of Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia. "And those papers are still secret today," Mr. Seifer said. "I was unable to get them under the Freedom of Information Act."

- The advent of anti-Communist fervor after Mr. Tesla's death. Because of his links to a country that had turned to Communism, Mr. Tesla's stature was further diminished by the McCarthy era, Mr. Seifer said.

- Plain xenophobia. America likes its heroes to be Americans, and Mr. Tesla was never quite taken for one even if he was among the chief architects of an age in which America has reigned supreme. By contrast, he has never lacked for recognition in his native country, Mr. Seifer said.

The author of two other books that have yet to be published, Mr. Seifer feared at one point that a similar fate awaited his Tesla biography, and it was on what he had decided would be his final attempt to find a publisher that he found one -- an attempt that he made himself when his agent, who had tried to sell the book for five years, finally gave up. At Birch Lane, Mr. Seifer's query landed on the desk of editor Allan Wilson, a septuagenarian with an interest in Mr. Tesla and his time. "He read my proposal, asked to see the manuscript and then made a bid on the book," said Mr. Seifer.

But Mr. Seifer is aware that publication is no guarantee that a book intended to rescue a genius from historical obscurity will itself ever be anything more than obscure.

"Wizard" has been favorably reviewed in book trade publications such as Publishers' Weekly, Booklist and The Library Journal, and Scientific American magazine will be running a story about it in its April issue. But Mr. Seifer has been frustrated by the lack of attention in the mass media.

Still, Birch Lane had enough faith in "Wizard" to have 10,000 copies printed -- an order twice as large as an author's first book normally draws -- and of those copies, 9,000 have already been shipped to stores, libraries and reviewers.

"It's doing well," said Mr. Seifer, who is himself doing as much as he can to promote the book. In addition to personally trying to interest the media in "Wizard," he has been appearing in bookstores to read and autograph it. His next such appearance will be at the Barnes & Noble in Warwick, R.I. March 23. He will read from 130-2.p.m. and sign copies until 4 p.m.

"I put a lot into getting this book done," he said. "I flew all over the world to research it. What I wanted to do was what was done for Einstein and Freud and Edison -- a work that would last."

Mr. Seifer lives with his wife in Narragansett, R.I. He has taught for more than 20 years at BCC's Fall River and New Bedford campuses.

Staff photos by Mike Valeri

Marc J. Seifer (middle photo), a psychology professor at Bristol Community College, has written a book on Nikola Tesla (1856-1943), a man who invented modern electricity, fluorescent and neon lighting and wireless telegraphy (top photo). In the 1898 photograph at bottom, Mr. Tesla sends 500,000 volts through his body to light a wireless fluorescent light.