TCBA Volume 4 - Issue 1

Page 14 of 18

Tesla Coils Resurrected

Experimental Electrics

Interesting Experiments with High Frequency Currents

By S. E. Newhouse, Jr.

Ever since the earliest time, man has looked with awe upon nature's marvelous electrical demonstrations in the form of lightning. It remained for Benjamin Franklin to be the first to attempt to learn something of the science connected with this remarkable manifestation of electrical energy. His well-known experiment with a kite in the eighteenth century marked the beginning of high voltage and high frequency experimentation. Since then man has made great strides in this field of electrical science. Such men as Tesla and Steinmetz have given us valuable information concerning the scientific nature of lightning.

The trend of modern electrical work is toward higher potentials; 220,000-volt lines have been put into successful operation, and even higher transmission voltages are being contemplated. Science must always keep a few years ahead of commercial progress, and for this reason many high voltage laboratories are at work making tests to determine what may be expected of future equipment. But there is much to be learned of the nature of lightning, which is a serious problem in high voltage transmission. High frequency currents which are of an oscillatory nature, as is lightning, have real practical application in this field of research, as it is quite common in practice to use high frequency currents in the commercial tests on insulators. The field of electro-therapeutics has made extensive use of these oscillatory currents in the X-ray and violet ray machines. High frequency furnaces are being built.

Here at Washington University, we have one of the best equipped high frequency laboratories in any school in the country. The feature exhibit of the annual Engineers' Day held each spring, is the high frequency demonstration. During the course of the day seven or eight complete demonstrations are given. These demonstrations consist of a large number of electrical “stunts” in which high frequency currents are used.

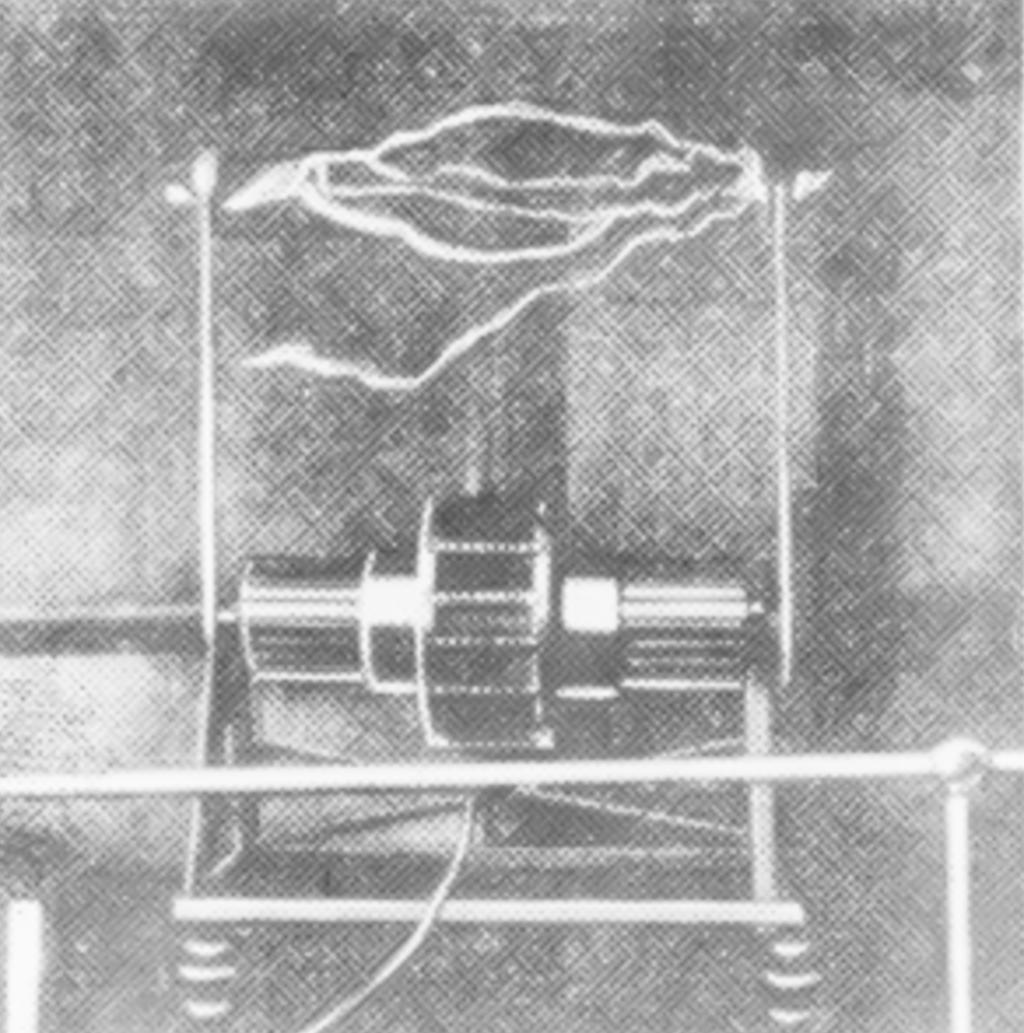

The “opening number” on the program is the demonstration of the four-foot Tesla coil, which gives a discharge of 54 inches in length, between its secondary terminals. This is followed by an exhibition of the seven-foot Tesla coil which gives a secondary voltage of more than 1,000,000 volts, the spark being nearly seven feet in length. A very startling and vivid effect is accomplished in all of these experiments by giving the demonstrations in a darkened room. The construction of the apparatus used will be described later.

Two high frequency electric signs are exhibited. On one sign a large butterfly is shown in a brilliant corona discharge, and on the other arc the words “Washington University,” likewise illuminated. This effect is obtained by pasting tinfoil on both sides of a pane of glass. The desired design is cut out of the tinfoil on one side and the two metallic sheets are connected across the terminals of the condenser to be shown in circuit diagram. The edges of the tinfoil give a corona discharge as do the plates of the condenser.

A large variety of Oudin coils have been built for the laboratory, and the demonstration of a number of these constituted the major portion of the performance. Oudin coils differ from Tesla coils in that one end of the secondary is connected to the primary and the discharge takes place from the free end of the secondary which usually terminates in a brass sphere; while in a Tesla coil the discharge takes place between the two secondary terminals, neither of which are connected to the primary.

A conical shaped Oudin coil was shown in operation; the discharge from the terminal resembling tongues of flame or writhing serpents. This coil is 15 inches high and gives a discharge nearly two feet in length in all directions from the terminal. The demonstrator showed how easily these discharges could be taken into the body, first with a copper strip held in the hand, and then with a metal strip held in the mouth. It is quite essential that the discharges should not enter or leave the body on the bare skin for a rather bad burn might result. The author has had a number of unpleasant experiences in this work. It is also very advisable for the demonstrator to stand on an insulated base while receiving the discharges. A heavy marble slab 20 inches by 50 inches laid in a wooden frame supported by four petticoat porcelain insulators was used for this purpose.

Another of the smaller type Oudin coils, when slightly de-tuned gave a beautiful fountain-like discharge of purple mist between the primary and the secondary. With any of the apparatus in operation, it was possible to light up Geissler tubes in the vicinity of the discharging coil. These were evacuated glass tubes about three feet in length, with a small tinfoil covering at each end. The various degrees of evacuation give a variety of colors of light within the different tubes, and very pretty effects are to be obtained.