Nikola Tesla Articles

Praise for a Man Who Made Edison Look Like a Tinker

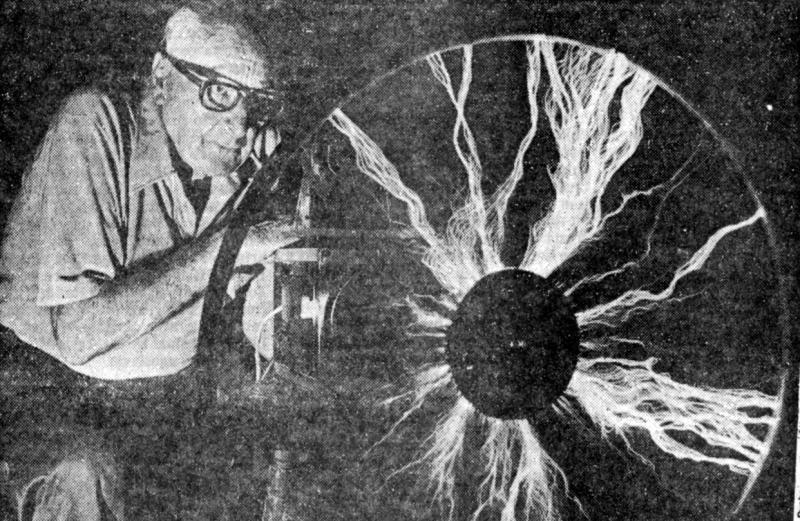

Ken Strickfaden of Santa Monica, who created the lightning bolts that jolted Frankenstein's monster into life in the movies, thinks it's shocking that more people didn't celebrate the 125th anniversary of Nikola Tesla's birthday Friday. William C. Wysock, a Monrovia sound systems manufacturer who habitually sets off 20-foot lightning bolts in his yard using a huge Tesla coil, thinks the late inventor's odd personal habits have clouded his astonishing achievements.

Nick Basura, a 56-year-old aircraft parts maker who lives in Los Angeles, said he has written 9,000 letters to people with praise and information about Tesla over the last 36 years.

"In this country, it is always Edison, Bell, Marconi and the Wright brothers," said Basura, with quiet indignation. "Edison was a tinker of toys compared to Tesla."

Not everyone would agree, but these three, and others like them around the country, have kept the memory of Nikola Tesla alive since his death in 1943. Although he could be as odd as he was brilliant, Tesla's inventions have had impact on almost all of modern technology, these three say.

Among the things they credit Tesla with are:

- The discovery of alternating current in 1887.

- The invention of radio, before Marconi.

- The Tesla coil, which is still used in many modern appliances, like the hair dryer, and which the Russians are said to be using for weather modification experiments.

- The use of radio for remote control, in everything from submarines to robots.

- The induction motor for washing machines.

- The self-starter for automobiles.

Still, lament true believers in Tesla, Edison gets five pages in the New World Encyclopedia, and Tesla gets half a column.

"I suppose there are a few people who have never heard of Tesla," sniffed Strickfaden, who has been interested in Tesla since he returned from World War I. "He put all of his life to solving problems, not seeking applause."

If Tesla hasn't found his proper place in the history books, it could well be because of his oddities. Or because reporters of the '30s concentrated on such crazy-sounding Tesla inventions as a "death ray."

Tesla had a somewhat weird reputation in the established scientific community.

Born July 10, 1856, in the village of Smiljan, Yugoslavia, Tesla was so afraid of germs, he carefully avoided shaking hands with anyone, and discarded gloves after wearing them a week. He used a dozen napkins at a meal, scrubbing each dish and piece of silverware. During lightning storms, he would lie on a couch near an open window, talking excitedly to himself.

When he was old, and cared more about his research than fame and fortune, Tesla once set off a moderate earthquake in his neighborhood with a vibrating machine. When the police arrived, they found Tesla, unable to stop the machine, demolishing it with a hammer.

Tesla turned down the Nobel Prize in 1912, because he would have had to share it with Thomas Edison, a believer in direct current, who had said of Tesla's discovery of alternating current, "My personal desire would be to prohibit entirely the use of alternating currents. They are as unnecessary as they are dangerous."

But most Tesla devotees have a higher opinion of their hero than Edison did.

Strickfaden is the special effects expert who made the terrifying lightning effects for all of the most famous American Frankenstein films, including the Mel Brooks film "Young Frankenstein." To make the effects, he used Tesla coils and other equipment based on Tesla's ideas.

"Tesla," said Strickfaden, "was one of the greatest geniuses to come out of the earth. He did things they said couldn't be done. ... He was the real father of radio, not Marconi. A U.S. Supreme Court patent decision, the year after Tesla's death, awarded him that honor."

Strickfaden made some respectable lightning bolts of his own for the original 1932 "Frankenstein," for "Bride of Frankenstein," "Son of Frankenstein" and "Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman." But he said one should not believe everything one sees in a Frankenstein movie. Photography can stretch a spark of a few inches into laboratory length.

"Even at that," said Strickfaden, "it takes 80,000 volts to generate a 4-inch arc. Those are real arcs from real generators in the Frankenstein movies, but some of the equipment that you will see is props."

Wysock, who has been fascinated by Tesla ever since he saw a Tesla coil at the Griffith Observatory when he was 5 years old, built the second largest homemade Tesla coil (16½ feet) in the United States. He has stopped passing auto traffic with it by generating 20-foot discharges from it in his front yard. It revs up to 6½ million volts, Wysock said.

Wysock, whose back-yard workshop in Monrovia adjoins his swimming pool, has performed some astonishing lightninglike displays.

These have included immense blue spider webs of electricity, arcing down into the Wysock swimming pool, and thunderous bolts shooting across the lawn. A friend, safe in Wysock's knowledge of electricity, was photographed with long sparks shooting out from all 10 fingers.

Wysock has a no-nonsense view of Tesla.

"There are some things about Tesla that I wish were non-existant," said Wysock. "Like cultists, who say that Tesla was extraterrestrial. I've lectured on Tesla, and afterward, some of these people have come up to me and said things like ‘did you know Tesla was a level-five communicator?' That sort of thing is all nonsense. It's the documented facts of Tesla's achievements that I am interested in."

Tesla owes much of what-fame he enjoys on the 125th anniversary of his birth to Basura. Since first reading an article about Tesla in 1945 in the Slavic-American magazine, Basura has, by his own calculation of the number at envelopes he has bought, sent at least 9,000 letters to people about Tesla.

Basura, a very quiet man who, like Tesla, has never married, sat on the bed in the same bedroom on Alice Sreet, where he was born. His bookcase brimmed with thousands of articles on Tesla. On another shelf were books on Tesla: "Lightning In His Hands," by Inez Hunt, poet laureate of Colorado Springs; and "Colorado Springs Notes, 1899-1900," published by the Tesla Museum of Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Basura's parents came from Yugoslavia, and it is partly patriotism that has led him to send Tesla material to anyone and everyone - scientists, magazine writers, librarians - known to have an interest in Tesla.

"I guess I'm a little bit the way Tesla was, in that I don't care much about money," said Basura. "He could have made millions from his patents, but he just wanted enough for research. Myself, I don't think I lose money on the things I send out. I get books on Tesla, and send them out to people who ask, at full price."

Wysock wanted a last word about Tesla. "It's important to remember that he was an extraordinary human being, but a real human being, not some creature from Mars, as some have depicted him," said Wysock.