Nikola Tesla Articles

Shedding light on neglected genius

Scientist Tesla experimented in Colorado

Nikola Tesla, noted electrical inventor, found dead in bed.

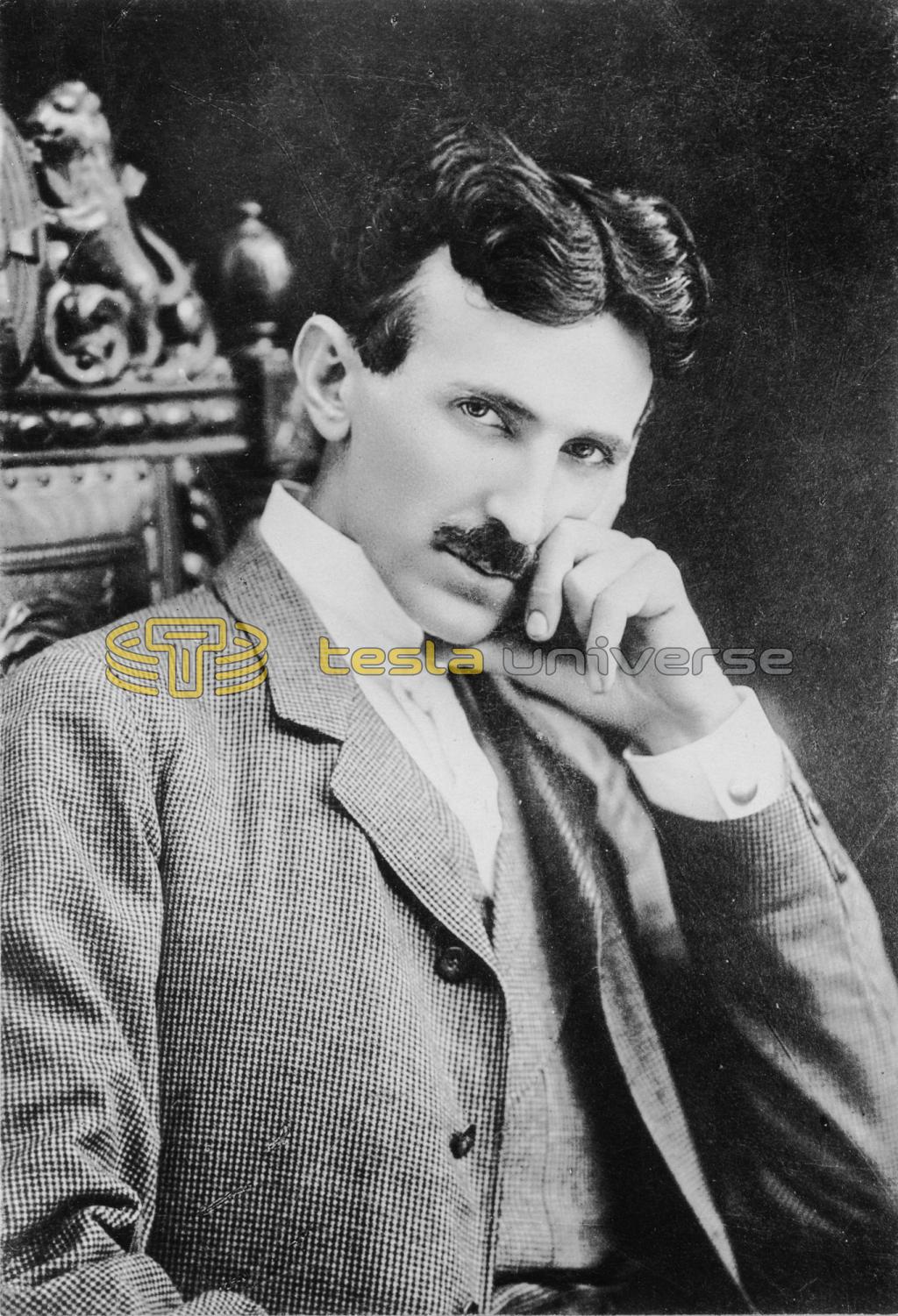

That Tesla's 1943 death was deemed less newsworthy than a kiddie rodeo was a harbinger of things to come: To this day, the Serbian inventor whose wild mind concocted alternating current and literally electrified the world remains to most an obscure figure.

"I was shocked this year when Time magazine did their millennial edition of the most important scientists of the 20th century and left him out," says Kat Tudor, founder of Smokebrush Center for Arts & Theater in Colorado Springs. "He didn't even make the top 100, and every motor in existence today is pretty much a motor that he invented."

A new play created by Tudor and husband Bob aims to help rectify history's oversight. "Tesla: Lost in Thought" runs at Smokebrush through July 22. A fanciful multimedia exploration of the inventor's eccentric mind, the play is teamed with "Tripping the Light Electric," a 20-minute historical film about Tesla's brief but momentous stay in Colorado Springs at the turn of the last century.

Electrifying

What: 'Tesla: Lost in Thought' and 'Tripping the light Electric'

When: Through July 22. 7 p.m. Wednesdays and Thursdays, 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, 2 p.m. Sundays

Where: Smokebrush Theater, 235 S. Nevada Ave., Colorado Springs

Tickets: $12-$15.

Call 719-444-0884.

It was at a laboratory just north of what's now Memorial Park that Tesla made what he considered his most important discovery in 1899: terrestrial stationary waves.

Fire had destroyed the inventor's New York lab four years earlier, and the experiments Tesla now had in mind were problematic in a big city. The wide open West seemed a better location, and when a Colorado Springs attorney with ties to the town's power company offered him free electricity, Tesla packed his bags.

Locals were abuzz about the enigmatic inventor, whose very presence sparked odd happenings. The grass around his lab glowed faint blue. Metal objects held near fire hydrants drew miniature lightning bolts from several inches away. Light bulbs within 100 feet of Tesla's building spontaneously lit. Sparks leapt from the ground, singeing people's feet through their shoes.

And that was only the warmup.

One night, using a gigantic version of his Tesla coil — a high-frequency, step-up transformer and the city's power supply, Tesla sent 10 million volts of electricity racing through the Earth's core to the planet's other side. Each time the wave bounced back to him, he added another charge, magnifying its power.

Tesla was searching for the wave's upper limit, with impressive results. As the surges built, lightning leapt from the 180-foot metal tower atop the inventor's laboratory. It built in a steady arc, extending 20 feet, then 50, then 80. The meadow in which the 43-year-old inventor watched glowed blue; apocalyptic thunder could be heard 22 miles away.

The lightning stretched 130 feet — still the most powerful man-made electrical surge in history — before Tesla's experiment came to an abrupt end. He had set the city's overloaded power generator ablaze; all the lights in Colorado Springs had gone out.

Such was the power of Nikola Tesla.

The life that would light up the world was remarkable from the start: Tesla entered the world precisely at the stroke of midnight between July 9 and July 10, 1856, in the village of Smiljan, Croatia.

In early life, he was plagued with peculiar, often inexplicable afflictions. As a young man, his physical senses for a time became painfully acute, The ticking of a watch sounded deafening; the footfalls of passers-by outside felt like an earthquake. Exposure to light was excruciating. The episode ended as mysteriously as it had begun.

From Childhood, Tesla was visited by blinding flashes of light, often accompanied by disturbing visions.

"To give an idea of my distress, suppose that I had witnessed a funeral or some such nerve-wracking spectacle," Tesla wrote. Then, inevitably, in the stillness of the night, a vivid picture of the scene would thrust itself before my eyes and persist despite all my efforts to banish it. ...

"To free myself of these tormenting appearances, I tried to concentrate my mind on something else I had seen and, in this way, I would often obtain temporary relief; but in order to get it I had to conjure continuously new images."

The curious problem and Tesla's solution reflect the inventor's remarkable ability to visualize. He rarely made notes or diagrams — detailed notes from his seven months in Colorado Springs are an exception — and built prototypes only in his mind.

"When I get an idea, I start at once building it up in my imagination," he wrote. "I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind. It is absolutely immaterial to me whether I run my turbine in thought or test it in my shop. I even note if it is out of balance. There is no difference whatever; the results are the same."

Tesla, Edison at opposite poles on electrical current

Tesla's inventive genius dazzled and threatened the world's best minds. Employed in 1882 as an electrical engineer with Continental Edison in Paris, the young Tesla soon found himself at odds with the company's president. A staunch advocate of direct current (DC), Thomas Edison was both contemptuous and fearful of the alternating current (AC) Tesla envisioned.

But direct current has serious drawbacks. It flows in one direction at a constant, unchangeable voltage and cannot be transmitted efficiently over long distances. The current envisioned by Tesla could change directions, be stepped up or down by transformers to vary voltage and could travel long distances over thin wires.

In short, it was a serious threat to Edison, whose campaign to smear Tesla and his brainchild was nothing short of scandalous. Revered as the inventor of the light bulb, Edison also created the first electric chair — pointedly using alternating current to generate bad publicity. He also regularly orchestrated public executions of horses and other animals to illustrate AC's "danger."

"After reading all the things about Edison and their little feud, I was appalled at Edison," says Ziggy Wagrowski, the Colorado Springs actor who plays Tesla in "Tripping the Light Electric."

But Tesla persevered to win powerful converts, among them George Westinghouse, who bought the patents for his AC system. It debuted commercially in southwestern Colorado in 1891, where a power plant using a 100-horsepower Westinghouse alternator sent electricity 2.5 miles over rugged terrain to a motor-driven mill.

Four years later, AC enjoyed a flawless public premiere at Niagara Falls, where Westinghouse used the system to transmit electricity to Buffalo, N.Y., 22 miles away.

Nikola Tesla had won the war of the currents.

The success of alternating current coincided with a remarkably productive period in Tesla's life, years he would later recall as "little short of continuous rapture."

In 1891 — the year he became an American citizen — he invented the Tesla coil, still widely used in radios, television, and other modern forms of communication. Bolts of lightning would leap from the humming coils, which Tesla frequently used in theatrical public lectures and demonstrations. Unwired bulbs illuminated at his touch; he turned lights off and on selectively from yards away. To the public, Tesla was a kind of magician.

But to science, he was pure invention. Consumed with the goal of wireless energy transmission, he envisioned free electricity for all, transmitted instantly across any distance.

"I would say that Edison was a businessman, a normal person who tries to make a profit anytime," Maglic says. "Tesla was sort of idealistic; he would give anything to do something big for the human race."

Such altruism, however, did little to endear Tesla to investors, who weren't interested in nothing for something.

But Tesla kept on creating. He's credited with inventing the radio and a precursor of X-rays, as well as remote-controlled boats and submarines. At an 1898 exposition, he successfully demonstrated a wireless ship that responded to verbal commands.

In the years before World War I, Tesla dreamed up the teleforce — apparently some sort of particle accelerator — as a defensive weapon that could knock down planes. He continued to refine and promote his "death ray" for decades. According to a New York Times article in September 1940 — more than a year before Pearl Harbor — the penetrating beam would melt airplane motors at a distance of 250 miles, "so that an invincible Chinese Wall of Defense would be built around the country against any attempted air attack by an enemy air force, no matter how large."

Though the government declined Tesla's death ray, he came up with another wartime notion: stations that would emit exploratory waves of energy, allowing operators to determine the location of distant enemy craft.

But like many of his inventions, the exploring ray was ahead of its time. It wasn't until World War II that the War Department came to appreciate the value of a remarkably similar innovation: radar.

Today, Tesla is revered in Yugoslavia, says Maglic, also a Serb. "He is considered almost like a saint... They have all kinds of organizations there that bear his name," Maglic says.

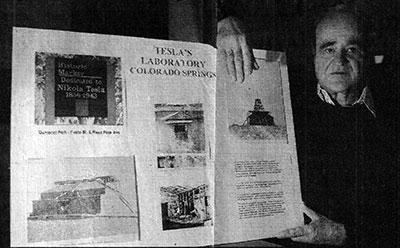

Maglic's former electrical engineering classmates have been instrumental in creating and maintaining the Tesla Museum in Belgrade since about 1950. In 1984, not long after Maglic moved to Colorado Springs to work for Honeywell, he co-founded The Tesla Society and a local museum dedicated to the inventor.

At its zenith, the society boasted 3,500 members worldwide, and 200 to 400 people typically attended an annual conference in Colorado Springs. But "mismanaged funds" ended the venture with bankruptcy in 1998, says Maglic, who calls resurrecting the Tesla Society and museum "the highest priority in my life."

Tesla inspires that kind of passion. One third-grade teacher has enlisted his students in a campaign to secure the inventor's "proper place in history." On a Web site that declares Tesla has been "erased at the Smithsonian," teacher John W. Wagner berates the institution for positioning Thomas Edison as America's "king of electricity" and ignoring Tesla's more significant contributions.

"Is it not classic irony that today Americans hold Edison in such high esteem, many even paying their electric bills to companies bearing his name, while Tesla, the real hero, is essentially erased from history at the Smithsonian?" Wagner asks.

Bad business sense may be mostly to blame for Tesla's obscurity.

"Tesla had no notion of money or fame, no idea how to market himself," Kat Tudor says of the inventor, who died destitute and alone.

"Plus, Edison was very interested in having Tesla become obscure ... He got on the wrong side of powerful men."

Tesla's many and profound eccentricities may also have helped discredit him. He hated physical contact and had a particular aversion to touching hair; he apparently never had a conventional romantic relationship.

Tesla was also compulsive. He required any repeated actions — footsteps taken while walking, for instance — to be divisible by three, with quantities of 27 (3 cubed) most prized. He calculated the precise volume of food he ate by dipping his food in water and measuring displacement.

"Nowadays, he would be called obsessive-compulsive," Tudor observes. "He probably would be medicated — and we would not have any alternating current whatsoever."

In later life, his scientific ideas became progressively more weird, no doubt contributing to a 252-page Tesla file compiled by the FBI. He proposed a "thought photography" machine that could read, record and transmit thoughts onto a screen. Tesla believed he had made contact with extraterrestrials while in Colorado Springs, and conceived of transmitters that would let earthlings talk with martians.

He also believed in interspecies communication, Tudor says — a concept that helps explain the aging Tesla's tender affection for a pigeon that visited him at the New York hotel where he later died.

"I have been feeding pigeons," he wrote, "thousands of them for years. There was one pigeon, a beautiful bird, pure white with light gray tips on its wings — that one was different.... I would know that pigeon anywhere. No matter where I was, that pigeon would find me when I wanted her. I had only to wish and call her and she would come flying to see me.

"I loved that pigeon... and she loved me. That pigeon was the joy of my life. If she needed me, nothing else mattered."

One night the bird flew into his room as Tesla was "solving problems." She had come to tell him she was dying, wrote Tesla, who described an intense light that streamed from the pigeon's eyes.

The inventor was bereft.

"When that pigeon died, something went out of my life," he wrote. "Up until that time, I knew with a certainty that I would complete my work, no matter how ambitious my program. But when that something went out of my life, I knew my life's work was finished."

Tesla died in his room on Jan. 7, 1943. The Associated Press death notice was short: "Nikola Tesla, 86, an electrical inventor noted for his development of systems of alternating current power transmission and distribution of electrical energy, died Thursday night.

"He was found dead in bed... at the New Yorker hotel. Members of the hotel staff said he had been in failing health for two years."

A light brighter than any Tesla had ever generated had gone out.

"He was such an eccentric genius," Tudor says. "Such a visionary."