TCBA Volume 19 - Issue 1

Page 11 of 18

Alvani and the Frog's Legs

By Floyd L. Darrow

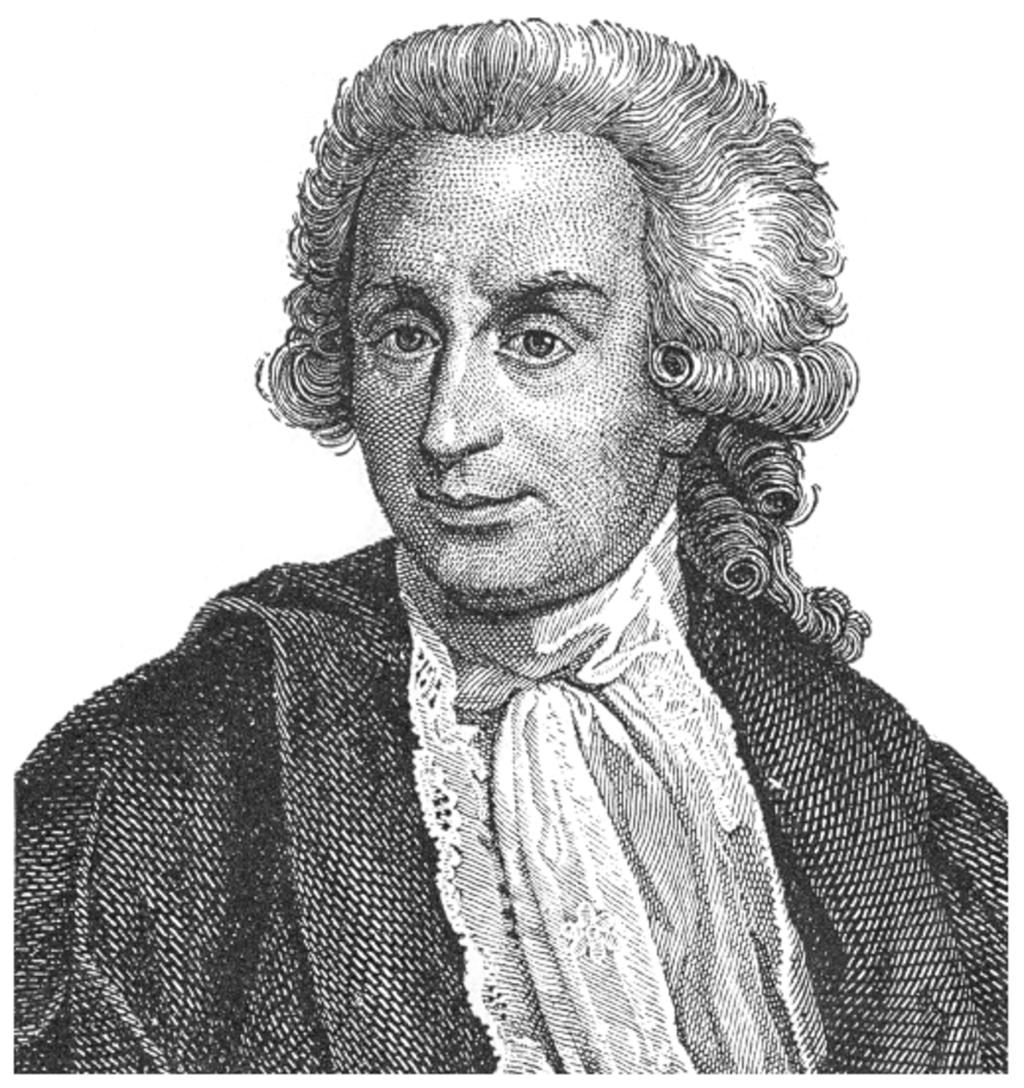

In the year 1791 Luigi Galvani, a professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna, Italy, made a discovery that placed his name high in the records of electrical achievement and introduced new words - galvanic, galvanized, galvanism - into the language.

Although the famous experiment was undoubtedly an accident, yet it is true that for years Galvani had been deeply interested in the effects of static electricity upon the nerves and muscles of the human body. One day in his laboratory he placed a dissected frog on a table near his electrical machine. Presently an assistant touched the nerves of the frog's thigh lightly with the point of a knife and immediately the muscles were thrown into vigorous contraction and began to twitch violently. Amazed at the unexpected result, Galvani began a thorough investigation of the circumstances surrounding this peculiar effect. It was found that the twitching occurred only at the instant when a spark was drawn from the electric machine. “Strong contractions took place in every muscle of the limb, and at the very moment when the sparks appeared.”

Galvani next determined to discover whether lightning would have similar effects. Although mindful of the danger attending such experiments, he erected a metallic conductor on the highest portion of his house and carried it to his laboratory below. At the approach of a thunderstorm Galvani suspended on the wire a dissected frog. To the feet of the frog he attached a second wire, which he grounded by allowing it to slip into a near-by well. In the words of Galvani himself: “The results came about as we wished. As often as the lightning broke forth, the muscles were thrown into repeated violent convulsions, so that always, as the lightning lightened the sky, the muscle contractions and movements preceded the thunder and, as it were, announced its coming. It was best, however, when the lightning was strong.”

Galvani continued to experiment with frogs' legs for a number of years. In his efforts to learn the effects of “the daily quiet electricity of the atmosphere” he hung several frogs from an iron railing by means of brass hooks passing through their spinal cords. After several days of fruitless waiting, he endeavored to reproduce the twitching of the muscles by pressing the brass hooks against the iron railing. Immediately the muscles responded, as they had previously done with the discharge from the electrical machine and the lightning flash. Evidently electricity from some source was again present. Without knowing it, Galvani had brought about the conditions necessary for an electric cell and a current had flowed through the nerves of the frog. The saline juices of the frog's legs, producing unequal chemical action upon the iron and the brass at the point of contact, had generated electricity. For the first time in history direct observation had been made of the production of an electric current and, crude as the mechanism was and though totally misunderstood, great results were to flow from this discovery.

Curiously enough, Galvani invented a theory of “animal electricity” to account for the effects of his experiments and never appreciated the true significance of his great discovery.

He wrought more wisely than he knew; and future generations of scientists reaped the benefit of his early experiments. His work inspired his fellow countryman Alessandro Volta to make one of the great basic inventions in electrical science, the voltaic battery, which opened up a new era in electrical progress.

LUIGI GALVANI, 1737-1798

His investigations of the muscular action of frogs when in contact with metals led to the discovery of galvanic, or voltaic, electricity